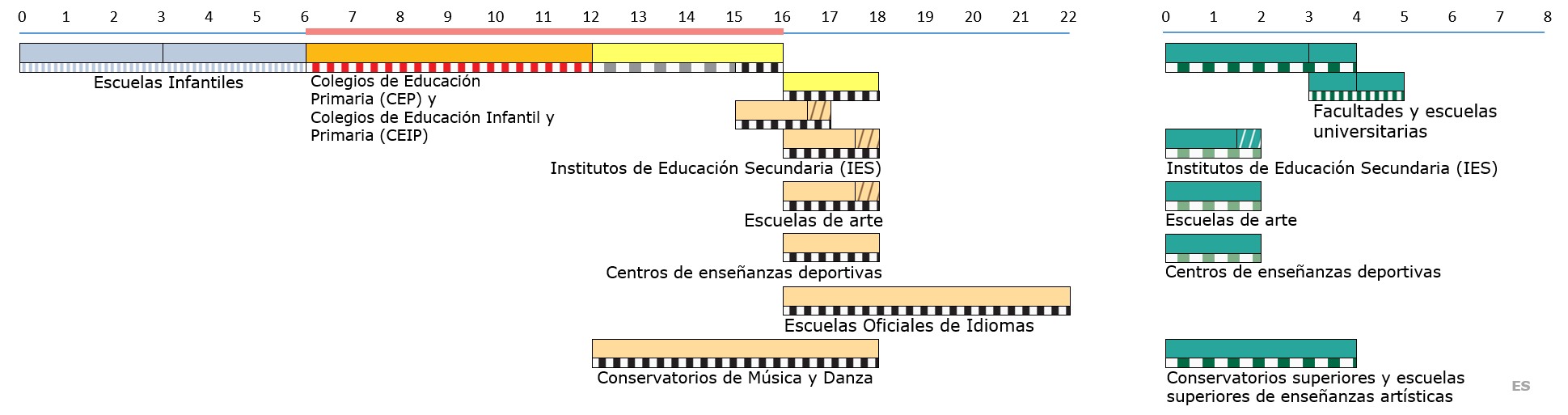

1. Key indicators

Figure 1 – Key indicators overview

| Spain | EU-27 | ||||||||

| 2010 | 2020 | 2010 | 2020 | ||||||

| EU-level targets | 2030 target | ||||||||

| Participation in early childhood education (from age 3 to starting age of compulsory primary education) |

≥ 96% | 96.6%13 | 97.3%19 | 91.8%13 | 92.8%19 | ||||

| Low achieving eighth-graders in digital skills | < 15% | : | : | : | : | ||||

| Low achieving 15-year-olds in: | Reading | < 15% | 19.6%09, b | 23.2%18 | 19.7%09, b | 22.5%18 | |||

| Maths | < 15% | 23.8%09 | 24.7%18 | 22.7%09 | 22.9%18 | ||||

| Science | < 15% | 18.2%09 | 21.3%18 | 17.8%09 | 22.3%18 | ||||

| Early leavers from education and training (age 18-24) | < 9% | 28.2% | 16.0% | 13.8% | 9.9% | ||||

| Exposure of VET graduates to work based learning | ≥ 60% | : | : | : | : | ||||

| Tertiary educational attainment (age 25-34) | ≥ 45% (2025) | 40.3% | 47.4% | 32.2% | 40.5% | ||||

| Participation of adults in learning (age 25-64) | ≥ 47% (2025) | : | : | : | : | ||||

| Other contextual indicators | |||||||||

| Education investment | Public expedienture on education as a percentage of GDP | 4.5% | 4.0%p | 5.0% | 4.7%19 | ||||

| Expenditure on public and private institutions per FTE/student in € PPS | ISCED 1-2 | €5 78512 | €6 07918 | €6 07212,d | €6 35917,d | ||||

| ISCED 3-4 | €6 77512 | €7 52518 | €7 36613,d | €7 76217,d | |||||

| ISCED 5-8 | €9 15512 | €9 47718 | €9 67912,d | €9 99517,d | |||||

| Early leavers from education and training (age 18-24) | Native | 25.1% | 13.2% | 12.4% | 8.7% | ||||

| EU-born | 39.7% | 31.2% | 26.9% | 19.8% | |||||

| Non EU-born | 44.0% | 28.5% | 32.4% | 23.2% | |||||

| Upper secondary level attainment (age 20-24, ISCED 3-8) | 61.5% | 75.9% | 79.1% | 84.3% | |||||

| Tertiary educational attainment (age 25-34) | Native | 45.3% | 52.4% | 33.4% | 41.3% | ||||

| EU-born | 31.5% | 35.0% | 29.3% | 40.4% | |||||

| Non EU-born | 20.7% | 31.1% | 23.1% | 34.4% | |||||

Source: Eurostat (UOE, LFS, COFOG); OECD (PISA). Further information can be found in Annex I and in Volume 1 (ec.europa.eu/education/monitor). Notes: The 2018 EU average on PISA reading performance does not include ES; the indicator used (ECE) refers to early-childhood education and care programmes which are considered by the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) to be ‘educational’ and therefore constitute the first level of education in education and training systems – ISCED level 0; FTE = full-time equivalent; b = break in time series, d = definition differs, p = provisional, := not available, 09 = 2009, 12 = 2012, 13 = 2013, 17 = 2017, 18 = 2018, 19 = 2019.

Figure 2 - Position in relation to strongest and weakest performers

Source: DG Education, Youth, Sport and Culture, based on data from Eurostat (LFS 2020, UOE 2019) and OECD (PISA 2018).

2. Highlights

- Spain maintained a good school climate during the COVID-19 pandemic, however students’ well-being was negatively affected.

- The new Education Act plans a thorough modernisation of the education system with several reforms and large investments. It will receive EU support through the National Recovery and Resilience plan.

- Girls outperform boys both in school and higher education, but remain underrepresented in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM).

- Higher education attainment is above the EU average, but low employability and skill mismatches persist. Enrolment in upper vocational education and training (VET) and in adult participation (notably for low qualified people) are improving but still remain a challenge.

3. A focus on well-being in education and training

National and regional policies on well-being focus mainly on measures against bullying and discrimination. Ensuring well-being at school is a priority in the Spanish education policy, seen as an essential component of quality education. Peaceful conflict resolution (notably in the case of bullying) and the support and protection of students against harassment, sexual abuse, violence, and discrimination figure among the main goals of the Spanish Education Act. All public education administrations (central, regional and local) have well-developed institutional and legislative frameworks to fight against bullying and discrimination1. All primary and secondary schools must adopt a school life strategy and follow clear protocols in case of bullying or cyberbullying, violence (particularly gender-based violence), and aggression against teachers. In higher education, the focus is on fighting against sexual harassment. Most universities have equity units, take preventative measures and follow protocols in cases of sexual violence or harassment. In May 2021, a new law on university coexistence was adopted2, establishing a common framework for the resolution of conflicts in a democratic way. It requests universities to draw up norms for coexistence, including prevention and remediation measures against harassment, discrimination and violence.

An observatory of school life3 disseminates good practices, monitors and provides guidance on how to improve school climate. Created in 2007, the observatory is composed of members from several ministries (social services, immigration, disability, gender, justice, interior, drugs, and youth), all Spanish regions (Autonomous Communities), the Ombudsman, education stakeholders (schools organisations, parents’ associations and trade unions), and specialists on school well-being.

International surveys point to a relatively good school climate. According to the 2018 OECD Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) (OECD, 2019a), bullying was less frequent in Spain (17% of students reported being bullied at least a few times a month) than the EU average (22%). However, bullying seems to be a more serious problem in primary schools. According to TIMSS 2019, 39% pupils in fourth grade claimed to have suffered from some form of bullying (EU22 average: 34%). 15 years old Spanish students have the highest sense of belonging to schools in the EU (87% vs an EU average of 65%). However, some disciplinary weaknesses have been observed. For example, compared to the EU average, more students had skipped a day of school (30% vs 25%) and 44% had arrived late for school in the 2 weeks prior to the PISA test (EU 41%).

School lockdown had a considerable impact on students’ well-being. According to Orgiles et al. (2020), 88.9% of the 431 Spanish parents participating in the study observed changes in the emotional state and behaviour of their children during the school lockdowns. The most frequent symptoms detected were difficulties in concentrating (69.1%), boredom (49.4%), irritability (43.2%), restlessness (38.8), nervousness (44.3%), loneliness (18.1%), uneasiness (30.4%) and worry (27.4%). However, according to a study by Martínez et al. (2020), younger children (8-10 year-olds) developed greater emotional well-being during quarantine. One explanation mentioned is the reduced pressure from the daily routines. 30% of children declared feeling comfortable in their homes with their family during lockdown. CANAE, the confederation of students’ associations, called for increased attention to students’ mental health during the pandemic4.

Stakeholders contributed to mitigating the negative consequences of the pandemic on students’ well-being. Education and health administrations supported teachers, parents, and students with guidance and orientation. Stakeholders (trade unions and students associations) were also active. CEAPA, the organisation of parents in public schools, issued a guide to prevent digital addictions during lockdown5. CANAE gathered some proposals to improve blended learning schemes and to overcome associated challenges6. Trade unions, such as ANPE, developed guidelines for teachers on how to cope with stress in times of COVID-197, and CSIF organised webinars for teachers on how to deal with anxiety and stress8.

Students with special educational needs experienced learning difficulties during the pandemic. Particularly during the three months of quarantine, children and adolescents with dyslexia showed less reading activity and less motivation to read. Parents of children with dyslexia reported significantly more stress, and nearly all parents of children with special educational needs reported difficulties in establishing study routines, negative impacts on their child's learning, and insufficient help from teachers on how to support their child’s learning (Soriano Ferrer et al., 2021).

Box 1: Education, the key to young Roma inclusion and well-being

The education promotion programme aims to prevent and reduce early school leaving among young Roma living in the region of Extremadura (western Spain). Project teams at district level are composed of an education mentor, a job counsellor, an intercultural agent and a job prospector. Together, they design and develop individualised pathways that comprehensively address the difficulties experienced by children up to the age of 16, and regularly monitor the implementation of measures. The mentors, usually coming from the Roma community itself, enhance Roma families’ participation in education, raise awareness among teachers on the needs of young Roma, and help to create links between the Roma community and the education system.

The 2018-2020 programme, which had a total budget of EUR 1.2 million (80% contribution from the ESF operational programme for the region of Extremadura) allowed 1 053 young Roma to participate. This is a significant increase compared to the 2016-2017 programme, which involved just 604 participants.

4. Investing in education and training

The proportion of spending on education as a share of GDP remains stable. In 2019, Spain spent 4% of its GDP on education, similar to the last 3 years, and below the EU average of 4.7%. For pre-primary and primary education, spending was 1.6% of GDP, for secondary education 1.5%, and for tertiary education 0.6%9. In 2019, scholarships represented EUR 2 billion (4% of total education spending). The Ministry of Education has made a remarkable effort to increase grants and scholarships for students: from EUR 1.5 billion in 2017 to more than EUR 1.9 billion in 2020-2021. For 2021-2022, the scholarship budget will increase again by EUR 128 m, benefiting around 850 000 students (390 000 from university)10. The minimum marks required to obtain a scholarship for studying for a Master’s degree decreased from 6.5 to 5 points on average.

Investment in education decreased during the last decade but increased again in the last 5 years. From 2010 to 2019, government spending on school education decreased overall by 1.5% (EUR 0.7 billion less, in real values) and by 9.1% (EUR 0.6 billion less in real values) in tertiary education. This contrasts with an average EU spending increase of 6.4% (4.2% in tertiary education). However, in 2015-2019, education expenditure increased (in real values) by 7.4% (above the EU-27 average of 5.4%): 8.4% in pre-primary and primary education, 11.2% in secondary and post-secondary education and 3.1% in tertiary education. The state budget for 2021 envisages an increase of EUR 4.9 billion, part of which (EUR 1.8 billion) will come from Spain’s Recovery and Resilience Plan11 (see Box 2).

Box 2: The National Recovery and Resilience Plan

The EU will disburse EUR 69.5 billion in grants to Spain under the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) to help the country emerge stronger from the COVID-19 pandemic. Investments related to education and skills represent more than 10% of the total RRF budget.

Spain’s Recovery and Resilience Plan envisages several reforms: operationalising the new Education Act; designing and implementing a new curriculum model for key competences; a VET modernisation plan; and a comprehensive reform of the university system. It includes investments to support these reforms, notably to: (a) create public places for the first early childhood education and care (ECEC) cycle (preferably 1-2 year-olds); (b) support the education guidance, advance and enrichment (#PROA+) programme in schools of particular educational complexity; (c) set up education support for vulnerable students, personal guidance and family units in educational and/or psychoeducational services located in school areas and districts; (d) train teachers and research staff; (e) improve digital university infrastructure; (f) promote the National Distance Education University (UNED); (g) upskill and reskill the workforce; and (h) enable the digital transformation, innovation and the internationalisation of VET.

The plan also includes investment in basic and advanced digital skills (AI, cybersecurity) and covers institutional reforms and capacity building of the national science, technology and innovation system (including universities) as well as the development a new scientific career scheme.

The plan envisages the creation of 1 000 service units to support vulnerable students and a support and guidance programme for low performing students to prevent early school leaving. It also envisages 135 000 new places in VET and the formal accreditation of professional skills acquired through work experience and non-formal training. It is also expected to significantly boost access to digital learning through investments in devices and skills, as well as through the development of online training courses.

5. Modernising early childhood and school education

The new Education Act (LOMLOE) plans to ensure universal access to ECEC. In 2019, ECE participation of children over the age of 3 (97.3%) remained stable compared to 2014, and above the EU average (92.8%) (Figure 3). Participation of children under 3 years-old in formal childcare has grown steadily in recent years (from 39.3% in 2016 to 57.4% in 2019) and is also above the EU average (Flisi and Blasko, 2019). Policies increasingly focus on improving access for children living in areas of higher risk of poverty or social exclusion as well as in rural areas, to further increase the participation of the under 3 age group.

Figure 3 - Participation in early childhood education of pupils from age 3 to the start of compulsory primary education, 2014 and 2019 (%)

Source: UOE, educ_uoe_enra21

There is a high level of segregation in Spanish schools. According to the Ferrer and Gortazar (2021) report, based on TIMSS and PISA outcomes, Spain is the EU country with the highest degree of school segregation12 at primary school level. However, the level of segregation is average in secondary schools. The report shows that socio-economic and immigrant backgrounds determine school choice and consequently segregation in Spain. The level of segregation differs significantly between regions, with Madrid having the highest rate (if the socio-economic factor is considered) and Cantabria the lowest. The new Education Act lays the foundations to fight against school segregation, with measures to avoid the concentration of vulnerable students in certain schools centres for socio-economic or other reasons.

A curricular reform aims to strengthen competence-based teaching. The reform of school curricula, envisaged under the new Education Act, will affect ECEC, primary and secondary education. It will include methodological guidelines for teaching and learning based on a competence-based curriculum. By incorporating 'soft skills', the new curricula respond to the Council Recommendation on key competences for lifelong learning13. They will also have a stronger focus on digital competences, education for sustainable development and citizenship education. At least 100 independent experts were involved in developing the curricula for all educational levels, with the help of a competence assessment evaluation framework. The reform will also include the preparation of support, guidance and teaching material, as well as training for teachers (at least 4 000 professionals). The roll out of the new curricula is expected by 2022-2023.

Early school leaving is decreasing, but regional differences and gender gaps persist. In 2020, the early leaving from education and training (ELET) rate was 16%, 1.3 pps lower than in 2019. However, the rate for boys was significantly higher (20.2%) than for girls (11.6%). There were also significant regional differences: four Autonomous Communities had ELET rates below 10%, another four had rates between 10% and 15%; seven had rates between 15% and 20%; and the remaining four had rates above 20%14. According to González-Anleo et al. (2021) and Soler et al. (2021), 30% of young people quitting education do so due to economic reasons (need to work to afford studies or other family needs) and 4.4% abandoned school due to social pressure (from family or peers).

Students’ performance in higher education entry exams seems to have changed during the pandemic. The number of students participating in the university admission exam (EBAU) increased by 17.6% on average (225 000 secondary graduates). This is likely due to the increased flexibility, as advised by the Ministry, on exam content and subject choices. Preliminary data on exam results indicate that the proportion of successful candidates was similar to the pre-pandemic period (93.2% vs 95%)15. Some regions showed lower success rates (3-5% less), which may be associated with a sharp increase in participants (20-30%). In most regions with around 14% more applicants, no significant changes in test results were observed. Regional disparities in success rates continue to grow (a gap of 9 pps in 2021 compared to 4.5 pps in 2016). Stakeholders and opposition political parties have raised concerns about regional differences in the content of exams and assessment criteria, which they see as a potential risk to a level-playing field. A successful candidate can enrol in any Spanish university, irrespective of the place of exam.

Girls outperform boys in educational attainment. The Ministry of Education report on gender equality (MEFP, 2021) points out that 84% of female students graduate from lower secondary education (ESO), and 63% from upper secondary (bachillerato), vs 74% and 48% of boys respectively. Seven out of 10 school teachers are women, and women occupy 66% of management positions in schools.

6. Modernising vocational education and training and adult learning

Enrolment in vocational education and training (VET) remains low; the COVID-19 crisis significantly affected the employment rate of VET graduates. In 2019, the share of upper secondary students in VET (36.4%), while growing (35.8 in 2018), remained below the EU average (48.5%). The employment rate of recent upper secondary VET graduates in Spain dropped from 66.0% in 2019 to 50.3% in 2020. The decline was stronger than in other EU countries and in line with the increase in youth unemployment.

The government is proposing a plan for a single integrated VET system. The 2020-2023 plan for modernising the VET system encompasses both initial and continuous VET with the goal of integrating them into a single system linked to the National Qualifications System. The plan also aims to support the continuing professional development of teachers through placements in companies.

The Spanish Recovery and Resilience Plan (RRP) will support the modernisation of the VET system. The contribution of EUR 2 bn will enable more than 3.3 million workers to receive certification of basic and professional skills. The plan also envisages a new VET law by 2022 to regulate the integrated VET system, approved by the Council of Minister on September 202116.

The National Catalogue of Professional Qualifications (NCPQ) will be reviewed and extended. The catalogue will include the design of new vocational training qualifications with a focus on strategic sectors. In initial VET, new short specialisation VET courses were developed for holders of an intermediate- or higher-level VET qualification to allow them to acquire occupation-specific and digital skills qualifications in the same field of studies.

The new Education Act (LOMLOE) envisages a VET reform. The 2020 law improves the regulatory framework for the VET system with the goal of increasing its overall flexibility and responsiveness. It also establishes the same qualification and training requirements for VET teachers as for secondary education teachers (Cedefop and ReferNet, 2021).

VET systems prioritised learners’ well-being during the COVID-19 crisis. The VET system made special arrangements for work placements and final assessments (e.g. online courses) to ensure the programme’s completion. Learners were provided with equipment and internet access, while teachers received teaching resources for digital education (Cedefop ReferNet Spain, 2020; Cedefop and ReferNet, 2021). Individualised mentoring schemes provided vulnerable young people with daily support for academic, health or personal issues (Cedefop, 2020).

Participation in adult learning grew, but only for the highly-qualified. Overall, adult participation in learning increased from 10.6% in 2019 to 11.0% in 2020 (EU average: 9.2%) thanks to the increase in online training. However, compared to 2019, the increase only applied to highly-qualified adults (+0.7 pps), whereas low-qualified adults participated less (-0.3 pps). Consequently, gaps in the participation levels of both groups widened further in 2020 (18.2% of adults with tertiary education vs 3.5% for the less qualified).

The RRP will help to increase adult digital skills. The plan will support the national digital competences plan with EUR 3 bn in 2021-2023. Around 2 600 000 people and 450 000 workers in Spain will benefit from digital skills training to improve their competences and employability. The RRP will also provide upskilling and reskilling training for the employed and unemployed alike, especially the low-skilled, targeting 1 000 000 workers.

7. Modernising higher education

A comprehensive reform of the higher education system in the pipeline. The reform aims to promote access to higher education, reorganise the teaching offer, foster teaching and research capacity, promote the requalification and mobility of teaching and research staff and guarantee the quality and good governance of universities. The reform is being developed after a process of hearing and consultation with relevant stakeholders from the university education community and responds to the recommendations made by the Conference of Rectors of Spanish universities (CRUE) (see below).

New standards for higher education institutions. The Government approved in July a new regulation on the establishment of new Universities, aimed to enhance their quality by strengthening institutional accreditation and internal systems of quality assurance17. Moreover, in September the reform of the organisation of study courses and quality assessment procedures was approved. The government plans to reform the organisation of study courses and quality assessment procedures18, possibly changing from the current 3+2 system to 4+1. This could increase the quality of Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees and make it easier to complete a Master’s degree by lowering the tuition fees, making them more affordable, notably for low income students. It also plans to make the current academic offer more relevant to the labour market. Currently, only 24 out of 3 880 university degrees follow 3+2 system (most at private universities in the Catalonia region). Universities participating in European university alliances (24 out of 85 campuses) will be allowed to use the 3-2 system. The impact of this reform on the Bologna process and on the automatic mutual recognition of academic titles is to be seen.

Enrolment and completion rates remain high, but study choices are not aligned with labour market needs. The tertiary education attainment at 47.4% in 2020 is one of the highest in the EU (above the average of 40.5%)19 and keeps growing (0.9 pps higher than in 2019). The rate is higher for women than men (53.5% vs 41.3%) (Figure 4). In the last 5 years, the number of STEM graduates decreased almost by 10%20, as well as the number of female STEM graduates declined (from over 32 000 in 2015 to around 28 000 in 2019). In 2020, the employment rate of recent tertiary graduates in Spain (75.9%) was below the EU average (83.7%)21. The share of ICT graduates in 2019 remains at 4.2% (above the EU average of 3.9%). The share of ICT specialists in the labour force is growing (3.8% vs 3.6% in 2019)22, including female ICT specialists (1.14% vs 1.04% in 2019), but both are still below the EU average (4.3% and 1.39% respectively in 2020). ANECA, the National Agency for quality evaluation and accreditation, developed in collaboration with 64 universities a reference guide for universities to improve the employability of their graduates23.

Figure 4 -Tertiary educational attainment (25-34) by sex, 2020

Source: Labour Force Survey, edat_lfse_03.

A 2030 strategy for Spanish universities will transform higher education24. The CRUE strategy recommends measures to: (1) adapt the university education offer and it make more flexible; (2) implement new teaching models for distance/blended learning, including remote assessment of students; (3) support the role of universities in long-life learning (new formal and non-formal teaching/learning models for upskilling/reskilling); (4) promote internationalisation (joint EU-wide degrees and mutual grade recognition); (5) modernise and improve quality assurance and appraisal systems for teaching staff and higher education institutions; (6) boost and attract talent (including from the private sector) and increase teachers/students mobility; (7) foster technology transfer, entrepreneurship and university-business cooperation; (8) make universities more suited to the green and digital transition and make them more inclusive; (9) develop new financial models and multiannual financial frameworks; and (10) update the staff regulation to create new models of recruitment, career development and closing gender and inclusiveness gaps.

Tuition fees vary widely between universities. The cost of a university credit (equivalent to 10 teaching hours) differs by up to 50% between Spanish universities. For 2020-2021, the government capped the fee per credit of Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees at EUR 18.4625. Universities exceeding that limit have to lower their fees by 2022-2023. Madrid and Cataluña have the highest average fees (around EUR 24) and the Canary Islands and Galicia have the lowest (around EUR 12)

The pandemic affected higher education. CRUE issued a report describing how universities reacted to the pandemic26 and making a number of policy recommendations, notably to: guarantee the highest possible students participation in face-to-face courses; provide more scholarships and enough digital means for online teaching; optimise the use of the learning environment; further develop digital technologies for learning; and increase teachers’ digital competences, including applying digital assessment techniques.

8. References

Cedefop (2020). Digital gap during COVID-19 for VET learners at risk in Europe. Synthesis report on seven countries based on preliminary information provided by Cedefop’s Network of Ambassadors tackling early leaving from VET. https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/content/digital-gap-during-covid-19-vet-learners-risk-europe

Cedefop ReferNet Spain (2020). An unexpected challenge for VET in Europe 2020. https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/news-and-press/news/spain-unexpected-challenge-vet-europe-2020

Cedefop; ReferNet (2021). VET REF: developments in vocational education and training policy database. Cedefop monitoring and analysis of VET policies. [Unpublished].

Ferrer, A. and L. Gortazar (2021) Diversity and freedom: reduction of school segregation and free choice of school (Diversidad y libertad: Reducir la segregación escolar respetando la capacidad de elección de centro), EsadeEcPol. https://dobetter.esade.edu/es/segregacion-escolar-esadeecpol

Flisi, S., and Zs Blasko (2019) A note on early childhood education and care participation by socio-economic background, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxemburg, 2019, ISBN 978-92-76-09694-8, doi: 10.2760/315380, JRC117663.

González-Anleo, J.M, Megías, I., Ballesteros, J.C., Pérez, A. and E. Rodríguez (2021), 'Spanish Young People 2021. New report of Spanish juvenile reality', SM Foundation.

MEFP (2021) Report on gender equality in education Ministry of Education and Vocational Training. https://www.educacionyfp.gob.es/mc/igualdad/igualdad-cifras.html

Martínez M.; Rodríguez, I., and G. Velasquez (2020). Lokdown children. https://www.observatoriodelainfancia.es/oia/esp/documentos_ficha.aspx?id=7073

Orgilés, M., Morales, A., Delvecchio, E.; Mazzeschi C. and J.P. Espada (2020) Immediate psychological effects of the COVID-19 quarantine in youth from Italy and Spain. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.579038

OECD (2019a), PISA 2018 Results (Volume III): What School Life Means for Students’ Lives, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/acd78851-en

OECD (2019b), PISA 2018 Results (Volume I): What Students Know and Can Do, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5f07c754-en

Soler, A. et al (2021). Map of ESL in Spain, (Mapa del abandono educativo temprano en España), Fundación Europea Sociedad y Educación. https://www.sociedadyeducacion.org/site/wp-content/uploads/Informe_AET_GENERAL_WEB.pdf

Soriano-Ferrer, M., Manuel Ramón Morte-Soriano., M.R., Begeny, J. and E. Piedra-Martínez (2021). Psychoeducational challenges in Spanish children with dyslexia and their parents' stress during the COVID-19 pandemic. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.648000

Annex I: Key indicators sources

| Indicator | Eurostat online data code |

| Participation in early childhood education | educ_uoe_enra21 |

| Low achieving eighth-graders in digital skills | IEA, ICILS. |

| Low achieving 15-year-olds in reading, maths and science | OECD (PISA) |

| Early leavers from education and training | Main data: edat_lfse_14. Data by country of birth: edat_lfse_02. |

| Exposure of VET graduates to work based learning | Data for the EU-level target is not available. Data collection starts in 2021. Source: EU LFS. |

| Tertiary educational attainment | Main data: edat_lfse_03. Data by country of birth: edat_lfse_9912. |

| Participation of adults in learning | Data for the EU-level target is not available. Data collection starts in 2022. Source: EU LFS. |

| Public expenditure on education as a percentage of GDP | gov_10a_exp |

| Expenditure on public and private institutions per student | educ_uoe_fini04 |

| Upper secondary level attainment | edat_lfse_03 |

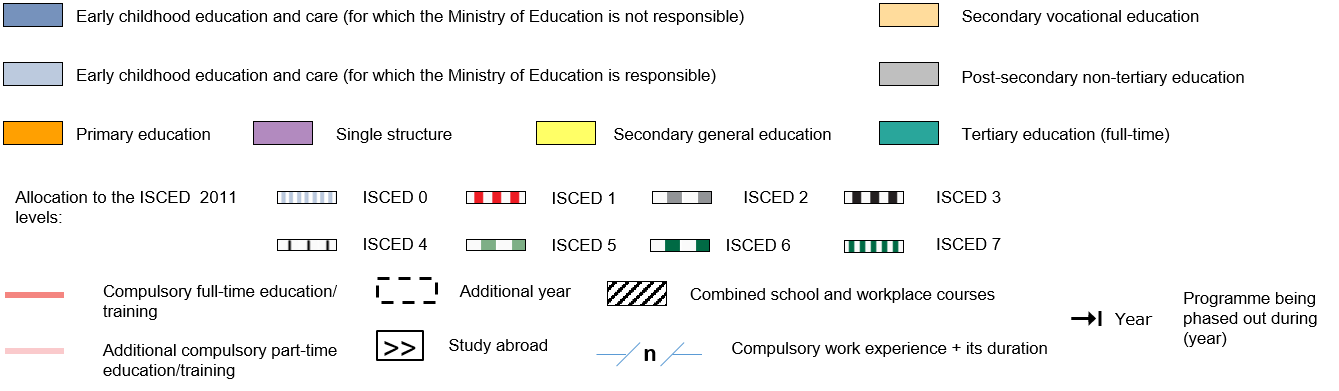

Annex II: Structure of the education system

Source: European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2021. The Structure of the European Education Systems 2021/2022: Schematic Diagrams. Eurydice Facts and Figures. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Any comments and questions on this report can be sent to: