1. Key indicators

Figure 1 – Key indicators overview

| Portugal | EU-27 | ||||||||

| 2010 | 2020 | 2010 | 2020 | ||||||

| EU-level targets | 2030 target | ||||||||

| Participation in early childhood education (from age 3 to starting age of compulsory primary education) |

≥ 96% | 88.7%13 | 92.2%19,d | 91.8%13 | 92.8%19 | ||||

| Low achieving eighth-graders in digital skills | < 15% | : | 33.5%18,†† | : | : | ||||

| Low achieving 15-year-olds in: | Reading | < 15% | 17.6%09,b | 20.2%18 | 19.7%09,b | 22.5%18 | |||

| Maths | < 15% | 23.8%09 | 23.3%18 | 22.7%09 | 22.9%18 | ||||

| Science | < 15% | 16.5%09 | 19.6%18 | 17.8%09 | 22.3%18 | ||||

| Early leavers from education and training (age 18-24) | < 9% | 28.3% | 8.9% | 13.8% | 9.9% | ||||

| Exposure of VET graduates to work based learning | ≥ 60% | : | : | : | : | ||||

| Tertiary educational attainment (age 25-34) | ≥ 45% (2025) | 25.5% | 41.9% | 32.2% | 40.5% | ||||

| Participation of adults in learning (age 25-64) | ≥ 47% (2025) | : | : | : | : | ||||

| Other contextual indicators | |||||||||

| Education investment | Public expedienture on education as a percentage of GDP | 6.7% | 4.4%p | 5.0% | 4.7%19 | ||||

| Expenditure on public and private institutions per FTE/student in € PPS | ISCED 1-2 | €5 23912 | €5 72718 | €6 07212,d | €6 35917,d | ||||

| ISCED 3-4 | €6 90712,d | €6 97018 | €7 36613,d | €7 76217,d | |||||

| ISCED 5-8 | €7 40312,d | €8 31718 | €9 67912,d | €9 99517,d | |||||

| Early leavers from education and training (age 18-24) | Native | 28.3% | 8.8% | 12.4% | 8.7% | ||||

| EU-born | :u | :u | 26.9% | 19.8% | |||||

| Non EU-born | 31.2% | :u | 32.4% | 23.2% | |||||

| Upper secondary level attainment (age 20-24, ISCED 3-8) | 59.1% | 85.3% | 79.1% | 84.3% | |||||

| Tertiary educational attainment (age 25-34) | Native | 26.3% | 42.5% | 33.4% | 41.3% | ||||

| EU-born | 27.9% | 47.9% | 29.3% | 40.4% | |||||

| Non EU-born | 17.0% | 34.0% | 23.1% | 34.4% | |||||

Source: Eurostat (UOE, LFS, COFOG); OECD (PISA). Further information can be found in Annex I and in Volume 1 (ec.europa.eu/education/monitor). Notes: The 2018 EU average on PISA reading performance does not include ES; the indicator used (ECE) refers to early-childhood education and care programmes which are considered by the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) to be ‘educational’ and therefore constitute the first level of education in education and training systems – ISCED level 0; FTE = full-time equivalent; b = break in time series, d = definition differs, p = provisional, u = low reliability, := not available, 09 = 2009, 12 = 2012, 13 = 2013, 17 = 2017, 18 = 2018, 19 = 2019; †† = Nearly met guidelines for sampling participation rates after replacement schools were included.

Figure 2 - Position in relation to strongest and weakest performers

Source: DG Education, Youth, Sport and Culture, based on data from Eurostat (LFS 2020, UOE 2019) and OECD (PISA 2018).

2. Highlights

- Schools are supported through several programmes to maintain students’ well-being and a good school climate. However, less attention is paid to how teachers cope with stressful conditions, notably during the pandemic.

- Public investment into education keeps growing and will be boosted with allocations from the Recovery and Resilience Facility, with a special focus on improving schools´ digital capabilities.

- Measures were adopted to mitigate the learning losses during the pandemic. Upper grade students were the most negatively affected.

- Portugal is making significant efforts, through policy reforms and investment in vocational education and training (VET) and adult learning, with EU support, to improve skills and competences of their workforce.

3. A focus on well-being in education and training

Student well-being and school climate are comparatively good. According to the 2018 programme for international student assessment (PISA) report (OECD, 2019a), 14% of students reported being bullied at least a few times a month, the second lowest in the EU (EU average: 22%). Indicators for disciplinary climate correspond broadly to the EU average: (i) 22% of students had skipped a day of school (EU average: 25%); (ii) 28% of students reported that their teachers have to wait a long time to quieten them down (EU average: 31%); and (iii) 50% had arrived late for school in the 2 weeks before the PISA test (EU average: 50%).

Dedicated programmes support well-being in education. The 'Health Promotion and Education Support Programme’ (PAPES)1, launched in 2014 by the Ministry of Education, has been focused on: (i) mental health and violence prevention; (ii) healthy nutrition and physical activity; (iii) addictive behaviours and dependencies; and (iv) relationships and sex education. The ‘Healthy School Seal’2 is granted to schools that promote health and well-being on a daily basis. The ‘Escolhas Programme’ (PE)3, created in 2001, aims to promote the social inclusion of children and young people from vulnerable socioeconomic backgrounds. This programme is co-financed by the European Social Fund (Alexandre et al., 2020). Furthermore, since 2019/2020, a Ministry’s Plan aims to prevent and combat physical bullying and cyberbullying as well as other forms of violence4. The Ministries of Labour, Solidarity and Social Security and the Ministry of Education issued guidelines for schools on children and young people at risk or in danger. Schools play an essential role in detecting warning signs and ensuring the well-being of children and young people5.

Schools received guidance on how to mitigate the impact of the pandemic including support for pupils’ well-being. In the academic year 2020/2021, the first 5 weeks were devoted to recovering and consolidating learning. The Ministry of Education published the ‘Guidelines for the recovery and consolidation of learning throughout the academic year 2020/2021’6, in view of the expected learning gaps during the lockdown period. Several measures were suggested: (i) promoting students’ well-being on their return to school; (ii) focusing on learning priorities; (iii) creating new support services for students and expanding those that already exist; and (iv) employing different ways to organise school schedules. Specific tutorial support was extended to students in primary and secondary education who did not succeed in the academic year 2019/2020. All schools set up mentoring programmes for students. During the pandemic, the Order of Portuguese psychologists also made several advisory documents and resources available online to support the education community in maintaining their emotional well-being during the confinement7.

Portuguese teachers are among the most stressed in Europe. Portugal is above the European average regarding stress levels associated with teaching, with 87% of teachers reporting quite a bit or a lot of stress at work (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2021). According to Varela et al. (2018), on a sampling of 10% of Portuguese teachers, 9 out of 10 teachers wanted to retire earlier and that there is a strong relationship between emotional exhaustion and a teacher’s age (for teachers over 55 years old, the percentage is close to 70%). In 2019, 46% of teachers in Portugal were aged at or over 50 (EU average: 39%) (OECD, 2020). A recent literature review (Mota, Lopes & Oliveira, 2021) of 46 studies published from 2000 to 2019, concluded that the average percentage of full burnout in Portuguese teachers was considerable.

The pandemic negatively affected higher education students’ and professors’ well-being. Higher education institutions were required to develop programmes to mitigate the negative effects of the pandemic on students, especially for first-year students8. The well-being of university professors was assessed by an online survey carried out in June-July 2020. It covered the teaching staff from the whole country (including the autonomous regions of Azores and Madeira). The study indicates that 37% of professors suffered burnout associated with professional activity, due to prolonged physical and psychological fatigue. Although 96% of the professors gave classes online, only 23% had previous experience in digital education.

4. Investing in education and training

The funding for education has increased, and seems to partly reverse the investment decrease which occurred over the last decade. In 2010-2019, general government expenditure on education (in deflated values) fell by 25.4% (EUR 3 billion), notably in primary and secondary education. Only spending in tertiary education increased by 4.8% (EUR 60 million). This contrasts with an average EU increase in education spending of 6.4%. In 2019, the downward trend stopped with an increase of 4 pps compared to 2018, reaching 4.4% of GDP. However, as in 2018 the level of spending is still below the EU average (4.7%)9. In pre-primary and primary education, spending in 2019 was 1.5% of GDP (1.2% by central government), 1.6% at secondary education (1.4% by central and 0.2% by local governments), and 0.6% in tertiary education (by central government)10.

Digital education will benefit from a major investment via EU funds. The ‘action plan for digital transition’11 is co-financed by the European Social Fund with a total budget of EUR 170 million for education digitalisation. The plan provides for the purchase of computers for all primary and secondary school pupils – giving priority to those belonging to disadvantaged families, to whom socio-economic support is provided – and improve school connectivity. For the 2020/2021 school year, the government provided approximately 450 000 computers with internet connectivity to schools. The plan also includes provision for a nationwide digital teacher empowerment plan to increase the pedagogical use of digital resources. The plan will address the training needs of all teachers in compulsory education by 2023. The digital training of teachers will be adjusted to their individual digital proficiency (based on teachers’ self-assessments of their digital skills) and followed by a personalised formative pathway.

Portugal plans to remove asbestos from schools buildings using EU support. The national programme for the removal of asbestos from school buildings (from ECE to compulsory education) was announced in June 2020. It is supported by several national and regional programmes under the European Regional and Development Fund. A total of 599 schools will benefit from the planned investment to remove 950 000 square meters of asbestos, notably those located in the Northern region and the Metropolitan area of Lisbon. In 2014-2020, 440 000 square metres of asbestos were removed from 200 primary and secondary schools12.

Box 1: The National Recovery and Resilience Plan

The EU will disburse EUR 13.9 billion in grants and EUR 2.7 billion in loans to Portugal under the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) to help the country emerge stronger from the COVID-19 pandemic. Investments related to education and skills represent about 13% of the total RRF budget.

The Portuguese Recovery and Resilience Plan aims to: (i) build childcare facilities and provide financial support to low-income families to increase their children’s ECEC participation; (ii) improve digital and STEAM (science, technology, engineering, arts and mathematics) education; (iii) invest in energy efficiency in school buildings and affordable accommodation for higher education students; and (iv) help modernise VET and upskill/reskill adults. For disadvantaged communities in the deprived metropolitan areas of Lisbon and Porto, it provides for investment into schools and projects to combat school failure and reduce the number of dropouts by means of fostering VET.

The Plan, among other things, provides for (i) around 600 000 laptops to be supplied to teachers and pupils and 40 000 projectors to primary and secondary public schools; (ii) 15 000 new accommodation places at affordable rents for university students, resulting in 10 000 more higher education graduates, including in STEAM fields; (iii) 22 000 training stations to be upgraded, and (iv) 365 specialised technology centres to be constructed or renovated for training in four strategic areas: industrial, renewable, informatics and digital technologies.

5. Modernising early childhood and school education

Participation in ECE among the 3+ age group is increasing and close to EU average. In 2019, ECE participation of children aged three or over increased to 92.2% (from 91% in 2018), well below the EU average (92.8%) and the EU-level target of 96% by 2030 (Figure 3). Regional differences are pronounced. The 2018 State of Education report13 indicated that the Lisbon Metropolitan Area remains the region with the lowest rates of pre-primary schooling for 3, 4 and 5- year olds (70.7%, 85.0% and 89.2%, respectively), while the Algarve and the Autonomous Region of the Azores were the regions with the highest rate of ECE participation, with 99% of 5-year-old children attending pre-school education.

The rate of early leavers from education and training keeps decreasing, but regional differences persist. In 2020, the ‘early leaving from education and training’ (ELET) rate was at 8.9% (10.6% in 2019), remaining below EU average (9.9%). Disparities in ELET rates range from 6% in the Centro region to 27% in the autonomous region of Azores.

A diagnostic study measured the impact of the first lockdown on students’ learning. It consisted of subject tests for students in mathematics, reading and science, as well as questionnaires to students, teachers, and schools’ managers. Conducted by the Educational Evaluation Institute (IAVE), a sample of 23 338 students from a universe of around 340 000 students from the 2020/2021 academic year from primary, lower and upper secondary education (third, sixth and ninth years) participated in the tests. Results were published in March and September 2021. The analysis showed learning difficulties particularly in the upper grades, where less than half of the students acquired the expected minimum level of competences. Sixth grade students were the most negatively affected by distance learning. Students who had family support fared better overall. In contrast, the youngest students (in the third grade) found it easier to learn from home.

Figure 3 - Participation in early childhood education of pupils from age 3 to the starting age of compulsory primary education, 2014 and 2019 (%)

Source: UOE, educ_uoe_enra21

Schools tried to maximise face-to-face education to mitigate learning losses. The Ministry of Education published a report (DGEEC, 2020) on how the education system was coping with the pandemic. Most schools tried to reorganise classes to reduce concentration and limit contagion (implementing shifts, maintaining bubbles, splitting classes, etc.). A vast majority of schools developed distance learning classes and participation rates were high. The report also points out that #EstudoEmCasa, a distance learning platform created during the pandemic, was only used as a teaching tool by around half of schools. Between April and June 2020, the percentage of schools that reported students who were exclusively accessing pedagogical content through #EstudoEmCasa declined significantly.

National assessments in lower and upper secondary education were altered. In response to the pandemic, tests to assess competences as well as the lower secondary final exam at ninth grade were cancelled. To address the major concern on students’ learning losses, based on the recommendations of a working group, the Plan 21|23 – Escola+ was launched in June 2021 with the aim of recovering and consolidating students learning plans for students in primary and secondary education14. Other temporary measures were adopted such as extending the academic year, and changing the school calendar (carnival holidays were suspended and the Easter break shortened).

6. Modernising vocational education and training and adult learning

Portugal is modernising VET with support from the RRF. As part of the national Recovery and Resilience Plan (RRP), Portugal is proposing a significant reform of its VET system to improve the low educational and qualification attainment levels as well as reduce the high number workers who lack basic and digital skills. The ultimate goal is to adapt skills development to current and future labour market needs and broaden education, training and lifelong learning opportunities for all. The dedicated component on skills and qualifications in the Portuguese RRP comprises measures to (i) strengthen the overall policy coordination of education and VET policies and (ii) modernise the VET offer regulated by the National Catalogue of Qualifications (CNQ) based on the system for anticipating which qualifications are needed in the labour market. Major investments are planned to modernise VET institutions and schools in upper secondary by means of (i) creating and modernising specialised technological centres, and (ii) broadening and modernising the public employment service’s network of professional training centres.

In 2020, Portugal launched a dedicated programme for the digital training of youngsters. The training programme ‘Youth + Digital’ (‘Jovem + Digital’)15 was launched as part of the action plan for the digital transition. It aims to align vocational training with labour market needs and improve the professional skills of young adults (aged 18 to 35) to increase their social inclusion and employability. The training courses are part of the national catalogue of qualifications leading to qualification at European Qualifications Framework (EQF) levels 4 or 5. They cover areas such as digital commerce, business intelligence, and social network management with a maximum duration of 350 hours (Cedefop and ReferNet, 2021; Cedefop ReferNet Portugal, 2021).

Portugal will encourage students to acquire key competences in VET. According to the 2018 law16, VET graduates must acquire 10 competences described in the students’ profile when they finish compulsory education17. These include (i) consciousness and body control; (ii) interpersonal relationships; (iii) personal development and autonomy; and (iv) well-being, health and environment (Cedefop and ReferNet, 2021; Cedefop ReferNet Portugal, 2018). The law, in line with relevant legislation18, also gave schools more autonomy in designing how learners could gain these competences. Since 2019, several training courses were provided to teachers and school principals to promote autonomy, curricular flexibility and inclusive education. In addition, monitoring teams from the Ministry of Education provide support to schools and promote good practices. Schools share their strategies in addressing learners’ needs and promoting their socio-emotional well-being (Cedefop and ReferNet, 2021).

The COVID-19 pandemic further hindered the slow progression in adult learning in Portugal. The share of adults (aged 25-64) participating in learning decreased by 0.5 pps. from 2019 to 2020 (it currently stands at 10.0%, still above the EU average of 9.2%). The share of low-qualified adults decreased even further (from 4.2% in 2019 to 3.3% in 2020, close to EU average of 3.4%). However, the share of high-qualified adults remained unchanged (47.8% in 2020, well above the EU average of 20.8%).

The Qualifica programme remains the main flagship initiative to address the persistent challenges in adult learning. Between 2017 and 2020, the European Social Fund supported the Qualifica programme, significantly contributing to adult education and training (483 471 registered participants by December 2020) and to the recognition, validation and certification of previously acquired skills and competences (562 620 partial and total certifications awarded)19. Yet, a significant proportion of the certifications obtained are partial in nature and there is scope to involve a more significant number of adults in the Qualifica programme. This can be achieved notably by recognising learning acquired in formal, informal and non-formal settings, quite relevant for low-skilled adults.

The RRP includes significant investments in adult education. Under the plan, support will be provided to the pilot project ‘Accelerator Qualifica’ that aims to set up procedures for the recognition, validation and certification of mature skills. In addition, the plan includes the national adult literacy plan (integrated as a component of the Qualifica programme) aimed to strengthen the population’s basic skills and therefore promote their social inclusion.

Box 2: VET professional courses in ‘Agrupamento de Escolas de Estarreja’

VET secondary double certification courses (three-year cycles) with both training in school and in a work environment, aim to develop the right professional competences for the labour market. These courses, funded under the ESF human capital operational programme, seeks to improve educational opportunities and the labour market relevance of education and training systems, facilitating the transition from education to work. The objective is also to strengthen vocational education and training systems and their quality, including through mechanisms for anticipating the skills needed for the labour market, adapting curricula and setting up and developing work-based learning systems, including dual-learning systems and apprenticeships.

Close cooperation with local employers’ skills demands allows training provision and labour market needs to be aligned. A total of 1 664 trainees were supported in the school cluster ‘Escolas de Estarreja’ between 2014 and 2021 for a total ESF budget of EUR 4 600 953. Results from the 2016-2019 cycle reveal an 83% share of graduated students. Around 80% of the students gained employment after they completed their studies or pursued further qualifications 6 months after concluding the course in 2019.

Website: https://www.aeestarteja.pt

7. Modernising higher education

The attainment of tertiary education is increasing, underpinned by measures to support access to and enrolment in higher education. Tertiary education attainment, for ages 25-34, increased in 2020 (41.9% vs 37.4% in 2019). Women continue to surpass men (49% vs 34.6%) (Figure 4). In 2019, the number of science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) graduates increased, but the share of female graduates remained static. For 2020-2021, the Ministry of Science, Technology and Higher Education (MCTES) made a number of the vacant study places reserved for international students available to nationals attending the national competition for access to higher education. To expand access to tertiary education, tuition fees were reduced, and more students were granted scholarships, notably students from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Figure 4 - Tertiary educational attainment (ages 25-34) by sex, 2020

Source: Labour Force Survey, edat_lfse_03.

The RRF will help build affordable student accommodation to address shortages. Investments in tertiary student accommodation may help enable access to and completion of tertiary studies. Around one third of university students come from more distant areas20, and high accommodation costs (notably in large metropolitan areas) may create a barrier for them to enrol in higher education, sometimes forcing them to abandon their studies. This affects in particular students from low-income households and those with special needs who need more inclusive facilities. In 2019, 600 more places were made available thanks to the collaboration of youth hostels, military infrastructures and churches. The creation of another 2 500 new places was planned for 2020 and 2 700 for 2021. The majority will be in the Lisbon and Porto metropolitan areas. The RRF will speed up the implementation of 2019 national students accommodation plan (PNAES) by providing EUR 375 million in loans to create additional accommodation for 15 000 students by 2025. However, while the Plan provides for 30 000 places to be made available by 2030, the current demand is much higher with 113 000 new students moving into university towns. The newly created places will cover the needs of around 25% of these students.

Higher education professors require further digital and pedagogical training. Digital skills of teachers in higher education were not developed as systematically as for those in compulsory education. Several researchers (Alarcão, 2015; Cunha, 2016; Leite, 2010; Xavier & Leite, 2019; Gomes & Tavares, 2017) highlight the need to invest in pedagogical and digital training for university teachers, as overall they are still very attached to more traditional teaching methods.

8. References

Abrantes, P., & Roldão, C. (2016). Old and new faces of segregation of Afro-descendant population in the Portuguese education system: a case of institutional racism? In: Conferência internacional da seção de educação comparada da sociedade portuguesa. Edições Universitárias Lusófonas, Lisboa.

Alexandre, J., Barata, M. C., Oliveira, S., Almeida, S., & Gomes, J. (2020). Avaliação externa do Programa Escolhas E7G: Relatório final. Lisboa: ACM. https://cld.pt/dl/download/7134548a-8416-4a10-9e9b-d1753b117613/AvalExternaE7G.pdf

Cedefop; ReferNet (2021). VET REF: developments in vocational education and training policy database.

Cedefop monitoring and analysis of VET policies. [Unpublished].

Cedefop ReferNet Portugal (2018). Portugal: linking VET programmes with the student exit profile. https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/news-and-press/news/portugal-linking-vet-programmes-student-exit-profile

Cedefop ReferNet Portugal (2021). Portugal: digital training to fight youth unemployment. https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/news-and-press/news/portugal-digital-training-fight-youth-unemployment

European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice (2021). Teachers in Europe: Careers, Development and Well-being. Eurydice report. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/eurydice/sites/eurydice/files/teachers_in_europe_2020_1.pdf

Mota, A.I., Lopes, J. and C. Oliveira (2021). Burnout in Portuguese Teachers: A Systematic Review. European Journal of Educational Research. Volume 10, Issue 2, 693 – 703. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1300166.pdf

OECD (2019a), PISA 2018 Results (Volume III): What School Life Means for Students’ Lives, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/acd78851-en

OECD (2019b), PISA 2018 Results (Volume I): What Students Know and Can Do, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5f07c754-en

OECD (2020). TALIS 2018 Results (Volume II): Teachers and School Leaders as Valued Professionals, TALIS, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/19cf08df-en

Varela, R., Della Santa, R., Oliveira, H.M., Coimbra de Matos, A., Rolo, D., Leher, & R., Areosa, J. (2018). Wear, Living and Working Conditions in Portugal: a multidisciplinary perspective. Lisbon: UNL. https://research.unl.pt/ws/portalfiles/portal/27307668/Desgaste_Condi_es_de_Vida_e_Trabalho.pdf

Annex I: Key indicators sources

| Indicator | Eurostat online data code |

| Participation in early childhood education | educ_uoe_enra21 |

| Low achieving eighth-graders in digital skills | IEA, ICILS. |

| Low achieving 15-year-olds in reading, maths and science | OECD (PISA) |

| Early leavers from education and training | Main data: edat_lfse_14. Data by country of birth: edat_lfse_02. |

| Exposure of VET graduates to work based learning | Data for the EU-level target is not available. Data collection starts in 2021. Source: EU LFS. |

| Tertiary educational attainment | Main data: edat_lfse_03. Data by country of birth: edat_lfse_9912. |

| Participation of adults in learning | Data for the EU-level target is not available. Data collection starts in 2021. Source: EU LFS. |

| Public expenditure on education as a percentage of GDP | gov_10a_exp |

| Expenditure on public and private institutions per student | educ_uoe_fini04 |

| Upper secondary level attainment | edat_lfse_03 |

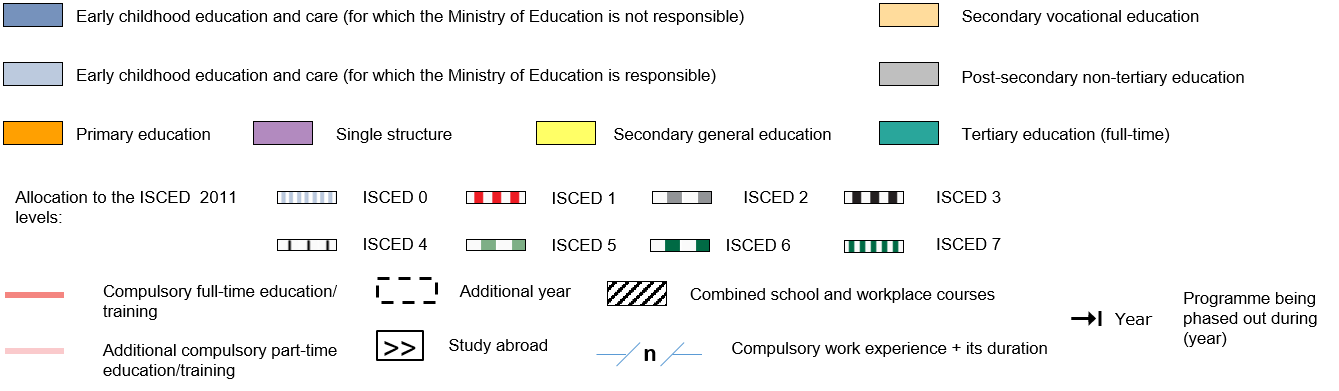

Annex II: Structure of the education system

Source: European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2021. The Structure of the European Education Systems 2021/2022: Schematic Diagrams. Eurydice Facts and Figures. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Any comments and questions on this report can be sent to: