1. Key indicators

Figure 1 – Key indicators overview

| Luxembourg | EU-27 | ||||||||

| 2010 | 2020 | 2010 | 2020 | ||||||

| EU-level targets | 2030 target | ||||||||

| Participation in early childhood education (from age 3 to starting age of compulsory primary education) |

≥ 96% | 89.9%13 | 88.4%19 | 91.8%13 | 92.8%19 | ||||

| Low achieving eighth-graders in digital skills | < 15% | : | 50.6%18 | : | : | ||||

| Low achieving 15-year-olds in: | Reading | < 15% | 26.0%09,b | 29.3%18 | 19.7%09,b | 22.5%18 | |||

| Maths | < 15% | 23.9%09 | 27.2%18 | 22.7%09 | 22.9%18 | ||||

| Science | < 15% | 23.7%09 | 26.8%18 | 17.8%09 | 22.3%18 | ||||

| Early leavers from education and training (age 18-24) | < 9% | 7.1% | 8.2% | 13.8% | 9.9% | ||||

| Exposure of VET graduates to work based learning | ≥ 60% | : | : | : | : | ||||

| Tertiary educational attainment (age 25-34) | ≥ 45% (2025) | 44.2% | 60.6% | 32.2% | 40.5% | ||||

| Participation of adults in learning (age 25-64) | ≥ 47% (2025) | : | : | : | : | ||||

| Other contextual indicators | |||||||||

| Education investment | Public expedienture on education as a percentage of GDP | 5.3% | 4.7% | 5.0% | 4.7%19 | ||||

| Expenditure on public and private institutions per FTE/student in € PPS | ISCED 1-2 | €15 05012 | €16 00818 | €6 07212,d | €6 35917,d | ||||

| ISCED 3-4 | €15 16912 | €17 15118 | €7 36613,d | €7 76217,d | |||||

| ISCED 5-8 | :12 | €33 51418 | €9 67912,d | €9 99517,d | |||||

| Early leavers from education and training (age 18-24) | Native | 6.0% | 7.8% | 12.4% | 8.7% | ||||

| EU-born | 11.0%u | 8.7% | 26.9% | 19.8% | |||||

| Non EU-born | :u | :u | 32.4% | 23.2% | |||||

| Upper secondary level attainment (age 20-24, ISCED 3-8) | 73.4% | 75.4% | 79.1% | 84.3% | |||||

| Tertiary educational attainment (age 25-34) | Native | 40.0% | 48.6% | 33.4% | 41.3% | ||||

| EU-born | 49.0% | 70.5% | 29.3% | 40.4% | |||||

| Non EU-born | 46.0% | 65.9% | 23.1% | 34.4% | |||||

Sources: Eurostat (UOE, LFS, COFOG); OECD (PISA). Further information can be found in Annex I and in Volume 1 ( ec.europa.eu/education/monitor). Notes: The 2018 EU average on PISA reading performance does not include ES; the indicator used (ECE) refers to early-childhood education and care programmes which are considered by the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) to be ‘educational’ and therefore constitute the first level of education in education and training systems – ISCED level 0; FTE = full-time equivalent; b = break in time series, d = definition differs, u = low reliability, := not available, 09 = 2009, 12 = 2012, 13 = 2013, 17 = 2017, 18 = 2018, 19 = 2019.

Figure 2 - Position in relation to strongest and weakest performers

Source: DG Education, Youth, Sport and Culture, based on data from Eurostat (LFS 2020, UOE 2019) and OECD (PISA 2018).

2. Highlights

- Bullying is evenly distributed among schools, but disadvantaged students show a lower sense of belonging.

- Public expenditure on education is well above the EU average and families received further support to mitigate the impact of the COVID-19 crisis.

- Learning deficits were discernible with particular regard to language skills in German, the teaching language for most subjects.

- Employment rates among young people declined during the pandemic, including for tertiary graduates.

3. A focus on well-being in education and training

In the international comparison, bullying is at average levels in Luxembourg, but pupils’ sense of belonging depends largely on a school’s socio-economic profile. Pupils’ well-being is not covered by the Education Acts. Compared to other PISA-participant EU countries, the sense of belonging among Luxembourg pupils would appear to be one of the factors with the strongest positive impact on their reading performance (Fig. 3) (OECD, 2019). The gap in the sense of belonging between pupils attending advantaged and disadvantaged schools is one of the highest in the EU, with pupils from an immigration background in particular reporting a lower sense of belonging. This suggests that performance could be improved by stronger inclusion measures. The share of pupils reporting that they were bullied at least a few times a month is below the EU average (20.6% vs 22.1%). In Luxembourg, the differences between schools in the levels of bullying incidents are smaller than in other countries. The proportion of pupils who reported being bullied at least a few times a month increased by 5 percentage points between 2015 and 2018 (EU average: 3.3 percentage points). One of the tools used to reduce bullying in Luxembourg’s European Schools - international schools primarily attended by the children of EU staff - is Finland’s KiVa anti-bullying programme, which has effectively reduced bullying in Finland and developed into a worldwide anti-bullying network. KiVa is based on the idea that the way peer bystanders behave when witnessing bullying plays a critical role in perpetuating or ending the incident. As a result, the intervention is designed to modify peer attitudes, perceptions and understanding of bullying. The programme specifically encourages students to support victimised peers rather than embolden bullying behaviour (European Commission, 2018).

Figure 3 - Change in reading performance when students feel that they belong at school, PISA 2018

Source: OECD (2019). Note: data for FI and IT are not statistically significant.

A regular report examines the situation facing young people. According to the 2008 Youth Act, the Minister responsible for Youth is in charge of presenting a 5-yearly report on this issue. The Act also specifies that interventions in the field must be based on evidence gathered on the situation facing young people. The report’s author is the University of Luxembourg, which also conducts the Youth Survey launched in 2019. The 2020 Youth Report (MENJE, 2021a) finds that the overall well-being of young people in Luxembourg is satisfactory but influenced by individual, social and structural factors. Disadvantaged families are less able to support their children. Even before the pandemic, the number of young people suffering from mental-health issues grew substantially. On a positive note, the report finds that formal and non-formal learning can play a central role in impacting positively on the well-being of young people. Another related survey focuses on pupils’ behaviour as regards health (HBSC, 2020). According to the most recent edition in 2018, in the space of 12 years the proportion of 11-18 year-old pupils becoming victims of mobbing (bullying of an individual by a group) fell from 13% to 8%. Another positive trend is lower consumption of alcohol and cigarettes and healthier eating habits among young people. Less positively, the proportion of pupils suffering from performance pressure and exam stress had increased over the same 12year period from 35% to 40%.

Life satisfaction and emotional well-being among children fell during the first lockdown. The report on ‘Subjective well-being and stay-at-home experiences of children aged 6 to 16 during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Luxembourg’ shows that children’s life satisfaction decreased sharply during lockdown (Kirsch, C., Engel de Abreu, P. M.J., Neumann, S., Wealer, C, Brazas, K., & Hauffels, I., 2020). While 96% of children said they were satisfied or very satisfied with their lives before the pandemic, only 67% were satisfied or very satisfied with their lives during it. The emotional well-being of children varied according to various factors. Significantly lower emotional well-being was reported by older children, children with a less advantaged socio-economic background and girls. Key dimensions of subjective well-being during the pandemic were the difficulty, quantity and content of school work when schools were closed, fear of illness, and satisfaction with the way adults listen to children. During the school closures, teachers received guidance from the Ministry of Education on how to detect pupil distress and how to address pupils’ issues and concerns.

Young people display alarming rates of suicidal thoughts and depression. The evaluation of the 2015-2019 national suicide prevention plan, a multi-sectoral policy including education, was published in March 2020 (Santé, 2020). The plan was based on the Australian ‘Living Is For Everyone (LIFE)’ initiative, the main goal of which is to make individuals, families and the community better able to respond quickly and in a coordinated manner to people’s distress. The evaluation of the action plan under the suicide prevention plan revealed that 15.2% of 12-18 year-olds had seriously contemplated suicide in the 12 months prior to the survey. 28% of the same age group suffered bouts of depression of at least 2 weeks during which they stopped their usual activities.

4. Investing in education and training

Public expenditure on education is above the EU average and was further increased to support parents during the school closure period. Public expenditure on primary to tertiary education per student, expressed in purchasing power standards, was the highest in the EU in 2018 (the most recent year for which data are available), standing at EUR 17 013.30 (followed by Austria with EUR 10 944.3). Public expenditure on education as a proportion of GDP is not a reliable indicator for Luxembourg because cross‐border workers and foreign capital invested in the country make a significant contribution to its GDP. Measured as a percentage of the total public budget, Luxembourg spent 11% on education in 2019, compared to an EU average of 10%. Staff remuneration accounts for 69% of education expenditure. Statutory salaries for teachers with 15 years of experience at each level of education are 66% to 79% higher than the salaries of other tertiary graduates (OECD, 2020). In order to allow parents to look after their children during school closures, special leave on family grounds was introduced. The amount budgeted for this was estimated at EUR 222 million, depending on for how long educational institutions were closed (Government, 2020).

Families received various forms of pandemic-related support. At the beginning of 2021, the child benefit allowance was increased. The basic monthly amount of child benefit was raised to EUR 265, combined with a monthly age supplement of EUR 20 for children aged over 6 and EUR 50 for children over 12. During school closures, parents were exempted from paying the childcare contribution. Over this period, the government continued to pay its contribution to childcare hours under the childcare voucher scheme (chèque-service accueil – CSA) in favour of education and care facilities, mini-crèches and certified childminders (Government, 2020).

The school population is growing and becoming ever more diverse. Between 2010 and 2020, the school-age population (4-16 year-olds) increased by 11% (vs 1% on average in the EU). The overall population grew by 24% in the same period, mainly due to immigration. In the 2020/2021 school year, pupils with Luxembourgish as their first language were the minority both in primary (34.3%) and secondary education (39.6%) (MENJE, 2021). Only 84.0% of pupils follow the national curriculum; others follow a European or international curriculum in public schools (4.4%) or private schools (11.6%). This high cultural and linguistic diversity poses particular challenges for the school system.

Box 1: The national recovery and resilience plan

The Luxembourg plan 1 is worth a total amount of EUR 183.1 million, of which EUR 93.4 million will be funded as non-repayable support under the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF). It aims to address structural challenges in skills, health, housing and governance and to foster the green and digital transitions 2 . Investments related to education and skills account for more than 5% of the total RRP budget.

5. Modernising early childhood and school education

Recent investments aim to increase access to and improve quality in early childhood education and care (ECEC). 88.4% of children take part in ECE from the age of 3, which is below the EU average (92.8%) and the new EU-level target of 96% set for 2030. Luxembourg has invested heavily in extending access to early childhood education and care and non-formal day care facilities in the last 10 years, nearly tripling the number of places and doubling the availability of childminders (Neumann 2018). Compulsory education starts with 2 years of pre-school from the age of 4, which can be supplemented with an optional year from the age of 3. The 2016 Youth Act established national quality standards in ECEC which all providers had to meet by September 2017 in order to be eligible for the government’s childcare voucher (CSA) co-financing scheme. This includes activities to familiarise children aged 1 to 4 with Luxembourgish and French. Childcare vouchers give parents reduced rates at crèches, after-school centres, mini-crèches and day care centres. In 2019, the childcare system was extended to include a new type of institution, mini-crèches. These are small-scale day care centres for children aged up to 12 that look after a maximum of 11 children.

Teachers and families received significant support during the school closures linked to the COVID-19 pandemic. A national learning platform, ‘schouldoheem.lu’, was created to provide digital learning materials and is updated daily with new content. It provides educational material for primary and secondary education, links to other interesting platforms, online challenges in various topics, links to helplines, etc. A second website, ‘kannerdoheem.lu’, provided recreational materials and ideas for non-formal learning, games and leisure activities for confined home spaces. In primary school, teachers provided pupils with a work plan and learning materials. Secondary school teachers gave regular assignments and feedback to their pupils in languages, mathematics and their specialisation subjects. All pupils were offered a two-week catch-up session before the start of the 2020/2021 school year, and additional coaching sessions were offered during the first term of the school year for pupils who were lagging behind.

The rate of early leavers from education and training (8.2%) is within the EU-level target (below 9%). This figure should be treated with caution because of the limited sample size. National estimates based on the actual number of young people under 24 who left the Luxembourgish school system without a diploma or leaving certificate during the reference year indicate that early school leaving decreased from 9.2% in 2016/2017 to 8.16% in 2019/2020. This rate also includes young people who had left the national school system but then enrolled in a foreign or private school later on. Boys are 83% more likely to leave school early than girls. Most young people are aged between 16 and 18 or in grades 9 and 10 when they drop out of school. These are the grades when pupils need to choose between different educational paths: academic (classique), general (général) or vocational (régime professionnel) (MENJE, 2021b). 97% of pupils who dropped out repeated a year at least once. Numbers repeating the school year remain high: by the end of primary education (age 12) 21.1% of pupils have repeated at least one school year (MENJE, 2021d). According to a survey by the National Youth Service (MENJE, 2021c), young people who have left education without a qualification are three times more likely not to participate in either education, employment or training at age 20 to 34 than their peers who have not dropped out from education. In 2020, the proportion of 20-34 year-olds not in education, employment or training (NEET) was 9.6% (EU average: 17.6%). To support reintegration, the SNJ contacts these young people and informs them about possible training and employment offers or alternative paths such as a period of voluntary service or a training workshop.

Pupils’ basic skills are below the EU average and strongly linked to socio-economic status. Luxembourg’s average levels of competence, as measured in the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), were lower in 2018 than in 2015 and 2012 in reading and science, but stable in mathematics. All were significantly lower than the respective EU average. The proportion of low achievers is well above the EU average in all three areas tested: 27.2% in mathematics, 29.3% in reading and 26.8% in science, compared to 22.9%, 22.5% and 22.3% respectively at EU level. In 2018, advantaged students scored 122 points higher than their disadvantaged peers, the largest such gap observed across all EU countries. Only 1% of disadvantaged students performed at the top levels (5 or 6), compared to the EU average of 2.5%. Pupils’ performance is heavily influenced by their ability to cope with the trilingual education system3. This system is challenging for all, but especially for pupils who speak a language other than Luxembourgish at home.

National tests give some insight into the pandemic’s impact on pupils’ learning development. Based on the results of the national competence tests (Epreuves Standardisées – EpStan), the University of Luxembourg analysed the influence of the pandemic on pupils’ learning outcomes. In pre-primary and primary education, the competency scores remained stable, except for a substantial decline in German in grade 3. The same trend was observed in lower secondary, especially among pupils from less advantaged socio-economic backgrounds, deepening existing inequalities. As German is the language of literacy training and teaching in Luxembourg, this deterioration is also likely to have repercussions for most other subjects. According to the accompanying survey, families coped well with home schooling and teachers communicated with their pupils regularly. Infrastructure was not a problem for accessing digital materials (LUCET, 2021). With an average class size at primary level of 15 pupils in public institutions – compared to the OECD average of 21 – Luxembourg was in a favourable position to reopen its schools while maintaining a safe distance of 1 to 2 metres between pupils and staff (OECD, 2020).

Digital sciences are being introduced in secondary education. In 2015, the government launched the Digital4Education strategy to boost young people’s digital skills. This covers a wide range of actions and options, such as raising cybersecurity awareness, ‘maker spaces’ that allow pupils to experiment with 3D printers, and free access to digital classrooms and the MS Office suite for teachers. Since the 2020/2021 school year, coding has been incorporated in mathematics classes in teaching cycle 4 (ages 10 to 11) and from 2021/2022 it will be taught across all subjects in teaching cycles 1 to 3 (ages 4 to 9). In secondary education, computer science will become a new subject in 2021/2022, including coding and computational thinking. From 2021/2022, some 18 secondary schools – about half of all secondary schools – will take part in a pilot scheme introducing digital sciences from grade 7 onwards through the 3 years of lower-secondary education. From 2022/2023, the new subject will be taught once a week in all secondary schools from grade 7 (MENJE, 2021c). In addition, the Luxembourg Tech School (LTS) programme offers extracurricular activities for 11-19 year-old pupils who are interested in the digital world and willing to learn about and apply technology in a real-world business context. Currently, LTS is present in more than 10 schools providing project-based personalised coaching for more than 200 pupils. As part of the strategy for improving digital education, the National Teacher Training Institute (Institut de formation de l’Éducation nationale – IFEN) offers new continuing professional development courses to both primary and secondary school teachers.

6. Modernising vocational education and training and adult learning

Vocational education and training (VET) graduates continue to enjoy excellent employment prospects. The employment rate among recent VET graduates is 100% (EU average: 79.1%). Nevertheless, the data need to be treated with caution because of the small sample size. In 2020, 61.9% of all learners in upper secondary education were enrolled in vocational education and training. The government took several measures to mitigate the impact of the COVID-19 crisis on the number of available apprenticeship places and thereby prevent early school leaving from VET colleges. In 2020, direct financial aid in the form of an apprenticeship bonus (between EUR 1 500 and EUR 5 000 per apprentice) was launched to encourage training organisations to offer apprenticeship places; the deadline for signing an apprenticeship contract was also extended.

A new technical programme in smart technologies replaces the former training programme in electronics. Since 2018/2019, five secondary schools have offered ‘Smart Technologies technical training’. The new 4-year technical programme uses a practice-orientated and project-based teaching approach. During the first 2 years of the programme, students learn the basics of electronics and smart technologies. In the second half of the programme, students can opt to specialise in one of five fields: robotics and automation; computing and electronics (‘infotronics’); renewable energy; smart energy; and e-controls. During the specialisation period, students work at a company in order to learn how to apply their skills in real life. Students graduate with a diploma in general secondary education, allowing them either to enter the labour market straight away or to continue their studies at tertiary level.

Overall participation in the labour market and adult learning is high, but lower among low-skilled and older workers. 16.3% of adults participated in learning, compared to an EU average of 9.2% in 2020. Participation is much less common among low-skilled workers (5.7%), increasing the risk of their skills becoming outdated and, ultimately, of early retirement. The employment rate among older workers (aged 55 to 64) remained particularly low (43.1%) in 2019, compared to an EU average of 59.1%. In its coalition agreement, the government pledged to promote the quality of lifelong learning by introducing a personal training account and training vouchers allowing all employees to follow basic training for digitalised professions free of charge. In June 2019, the establishment was announced of a new quality assurance agency (MENJE 2019d).

Various measures were taken to promote adult learning. The ‘Future Skills’ initiative launched in October 2020 allows jobseekers to follow a 3-month training course combined with a 6-month traineeship. The training focuses on soft, digital and project management skills. The ‘Digital Skills’ programme offers training vouchers to employees who benefited from the short-time work scheme between January and March 2021. In addition, the public employment service launched a ‘Basic Digital Skills programme’ for jobseekers in January 2020.

Luxembourg’s national recovery and resilience plan fosters skills development. There will be investments in vocational training programmes for jobseekers and workers placed in short-time work respectively. These vocational training programmes are expected to help mitigate the employment impact of the COVID-19 crisis. A complementary reform under the plan relates to the design of further vocational training programmes.

Box 2: European Social Fund project ‘Skill you up 2.0’

Total budget: EUR 599 500 (ESF: 50%)

Duration: 1 January 2020–31 December 2021

Target: 144 jobseekers

This measure builds on a previous scheme set up in 2018. It targets jobseekers aged over 30 who have a minimum of 5 years in secondary education, takes stock of their acquired skills (both technical and behavioural) and of their motivations, and draws up a concrete professional project for their reintegration into the labour market.

7. Modernising higher education

Tertiary attainment and graduate employment rates are among the highest in the EU. 60.6% of the population aged 25 to 34 holds a tertiary degree (EU average 40.5%), the highest rate in the EU. This is partly thanks to the high proportion of graduates in the migrant population (69.0%, compared to 48.6% of native Luxembourgers). The proportion of highly qualified women in this age group exceeds that of men by 11.3 pps (EU average 10.8). Study programmes at the University of Luxembourg are either bilingual, trilingual (French, German, English) or entirely in English. With a high proportion of international students, Luxembourg may have been more adversely affected by the travel restrictions linked to the pandemic than other countries (OECD, 2020).

Employment rates declined during the pandemic. The employment rate of recent tertiary graduates in 2020 was 84.7%, above the EU average of 83.7%, but almost 10 pps lower than in 2019 (Figure 4). Young people were hit particularly hard by the crisis: their unemployment rate increased by 7.9 pps within a year, reaching 25.1% in the first quarter of 2021. Having a tertiary degree carries not only an employment premium, but a considerable earnings advantage in most OECD countries. In Luxembourg, 25-64 year-olds with a tertiary degree and income from full-time, full-year employment earned 47% more in 2018 than full-time, full-year workers with upper secondary education, compared to 57% on average across OECD countries.

Figure 4 – Employment rates of recent graduates (20-34 years old) at ISCED levels 3 to 4 and 5 to 8, 2010-2020 (%)

Source: LFS, edat_lfse_24

University education was adapted to COVID safety standards in 2020/2021. All seminar rooms at the university were equipped with multimedia tools to enable students’ on-site participation on a rotation basis. The other students in the groups followed classes via video-conferencing. The university announced that the 2021 summer exams would be organised in a remote format and that it would extend hybrid teaching to the winter semester of 2021/2022. To support the mental and physical well-being of students and staff, a free programme, Campus Life, was launched in October 2020 with three focal points: Campus Sport, Campus Art and Campus Well-Being. The programme aims to encourage students and staff to try a new form of art, a new sport or a new discipline and to maintain or even improve their inner balance.

A new short-cycle programme was launched in October 2020 to protect young people from unemployment. The new 'Diplom+' post-secondary training scheme is a flexible programme over two semesters targeting young people who, having completed secondary education, are not enrolled in higher education and have yet to find employment. Participants are offered modules in general job skills such as project management and presentation and computer skills. On average, 25 hours per week are expected to be spent on study, leaving enough time for participants to search for a suitable job or study option. The programme can be interrupted at any time and completed modules are certified. Diplom+ entitles participants to benefit from study allowances. Take-up in the first year was modest, with 143 enrolments, of whom 22 youngsters were able to find a job or enrol in a study programme.

References

European Commission (2018): Kiva Antibullying Programme. https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=1251&langId=en&reviewId=205

Government (2020): Government of Luxembourg: Was sind die Folgen der Schließung von Kinderbetreuungseinrichtungen? https://guichet.public.lu/de/actualites/2020/decembre/29-consequences-fermeture-structure-accueil.html

Government (2020): Government of Luxembourg: https://guichet.public.lu/de/actualites/2020/decembre/29-consequences-fermeture-structure-accueil.html

HBSC (2020): Heinz, Andreas; van Duin, Claire; Kern, Matthias Robert; Catunda, Carolina; Willems, Helmut: Trends from 2006 - 2018 in Health Behaviour, Health Outcomes and Social Context of Adolescents in Luxembourg. https://orbilu.uni.lu/bitstream/10993/42571/1/HBSC%20Trend%20Report%202006_2018.pdf

Kirsch, C., Engel de Abreu, P. M. J., Neumann, S., Wealer, C, Brazas, K., & Hauffels, I. (2020): Subjective well-being and stay-at-home-experiences of children aged 6-16 during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Luxembourg: A report of the project COVID-Kids. https://orbilu.uni.lu/handle/10993/45450

LUCET (2021): University of Luxembourg, Luxembourg Centre for Educational Testing: What has the COVID-19 crisis done to our education system? https://wwwen.uni.lu/university/news/slideshow/what_has_the_covid_19_crisis_done_to_our_education_system

MENJE (2021a): Ministère de l’Éducation Nationale, de l’Enfance et de la Jeunesse: Rapport national sur la situation de la jeunesse au Luxembourg 2020: le bien-être et la santé des jeunes au Luxembourg. https://men.public.lu/fr/publications/statistiques-etudes/jeunesse/2021-06-jugendbericht.html

MENJE (2021b): Ministère de l’Éducation Nationale, de l’Enfance et de la Jeunesse: Education system in Luxembourg: Key figures School year 2020-2021. https://men.public.lu/fr/publications/statistiques-etudes/themes-transversaux/20-21-enseignement-chiffres.html

MENJE (2021c): Ministère de l’Éducation Nationale, de l’Enfance et de la Jeunesse: Jeunes décrocheurs et jeunes inactifs au Luxembourg. https://men.public.lu/fr/publications/statistiques-etudes/statistiques-globales/2021-05-jeunes-decrocheurs.html

MENJE (2021d): Ministère de l’Éducation Nationale, de l’Enfance et de la Jeunesse: Rapport d’activités 2020. https://men.public.lu/en/publications/rapports-activite-ministere/rapports-ministere/rapport-activites-2020.html

MENJE (2021e): Ministère de l’Éducation Nationale, de l’Enfance et de la Jeunesse: Digital Sciences. Une nouvelle discipline à l’enseignement secondaire classique et général à partir de 2021-2022. https://men.public.lu/en/publications/dossiers-presse/2020-2021/18-digital-sciences.html

Neumann S. (2018) : Non-formale Bildung im Vorschulalter, University of Luxembourg — Service de coordination de la recherche et de l’innovation pédagogique et technologique, Nationaler Bildungsbericht 2018, https://www.bildungsbericht.lu/

OECD (2019): PISA 2018 Results (Volume III) – What School Life Means for Students’ Lives. https://www.oecd.org/publications/pisa-2018-results-volume-iii-acd78851-en.htm

OECD (2020): Education at a Glance 2020. https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/

SANTE (2020) : Ministère de la Santé: Evaluation du Plan National de Prévention du Suicide du Luxembourg 2015-2019. https://sante.public.lu/fr/politique-sante/plans-action/plan-prevention-suicide-2015-2019/evaluation-rapport.pdf

Annex I: Key indicators sources

| Indicator | Eurostat online data code |

| Participation in early childhood education | educ_uoe_enra21 |

| Low achieving eighth-graders in digital skills | IEA, ICILS. |

| Low achieving 15-year-olds in reading, maths and science | OECD (PISA) |

| Early leavers from education and training | Main data: edat_lfse_14. Data by country of birth: edat_lfse_02. |

| Exposure of VET graduates to work based learning | Data for the EU-level target is not available. Data collection starts in 2021. Source: EU LFS. |

| Tertiary educational attainment | Main data: edat_lfse_03. Data by country of birth: edat_lfse_9912. |

| Participation of adults in learning | Data for the EU-level target is not available. Data collection starts in 2021. Source: EU LFS. |

| Public expenditure on education as a percentage of GDP | gov_10a_exp |

| Expenditure on public and private institutions per student | educ_uoe_fini04 |

| Upper secondary level attainment | edat_lfse_03 |

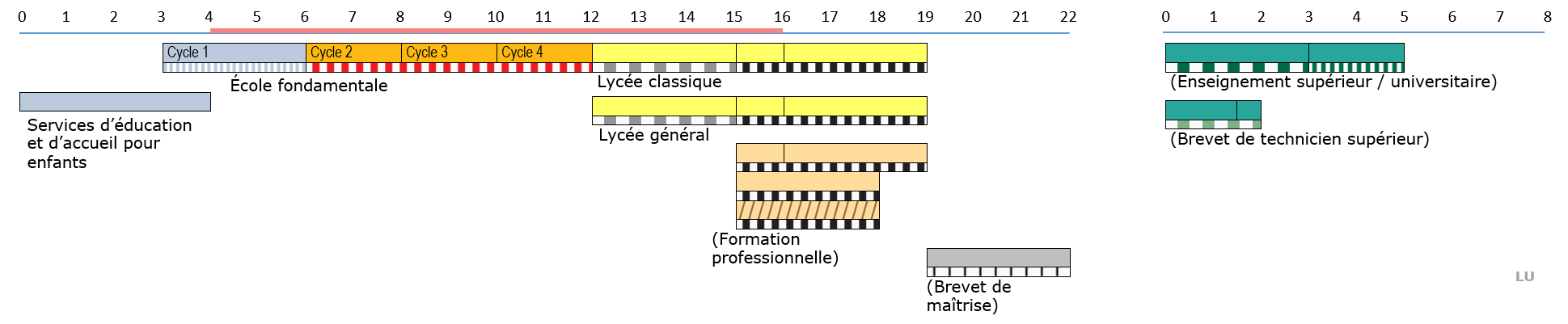

Annex II: Structure of the education system

Source: European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2021. The Structure of the European Education Systems 2021/2022: Schematic Diagrams. Eurydice Facts and Figures. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Any comments and questions on this report can be sent to: