5. Role of social partners in addressing labour and skills shortages

Fostering active involvement of social partners in policy-making is a key principle of the European Pillar of Social Rights and a common objective of the Member States. Social dialogue plays an important role in economic recovery and in alleviating labour market challenges in the wake of the energy crisis and the Russian war of aggression against Ukraine. Across the EU, social partners set skills development activities in some key sectors experiencing shortages, such as healthcare and construction. Collective bargaining helps to improve living and working conditions, such as wages, hours of work, access to training, leave entitlements, and health and safety measures. This section looks at the role of social partners in addressing the labour and skills challenges, including an overview of actions already in place.

Social partners play a key role in addressing labour and skills shortages by facilitating learning opportunities. Under various EU initiatives, social partners cooperate with other stakeholders in actions for skills development (see section 3.3.), ensuring that the workforce is equipped with skills suited to their needs. (373) They can also use cooperation to address technological upgrading and multiskilling. For their part, workers are supported to progress along their career paths and achieve greater job security. (374) Evidence suggests that employees perceive their career prospects to be 28% higher if a trade union or works council is present in their company or organisation. This is linked to better training opportunities, among other factors. (375) In addition to training, social partners also put in place actions targeting retention of workers and integration of migrants to the labour market.

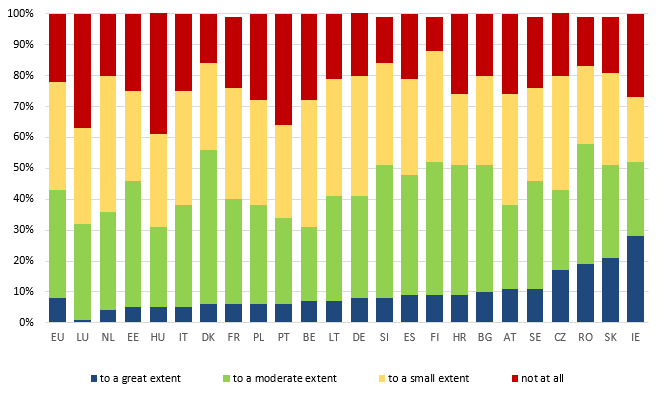

Chart 3.12

Trade unions have a positive impact on all workers’ career prospects

Involvement of social partners’ representatives in skills development at the work place, 2019, EU

Note: Data not available for Cyprus, Latvia and Malta.

Source: ECS 2019.

Despite adding value, social partners are only modestly involved in developing in-work training. In the period 2016-2019, employee representatives in 90% of establishments reported that in-work training took place in the establishments where they are represented. (376) However, the majority reported that they were involved only rarely, if at all, in determining skills needs at the work place (57%), although one-third reported being involved to a moderate extent (Chart 3.12). Representatives’ influence on management decisions in respect of skills development is generally low, with only 8% reporting being involved to a great extent.

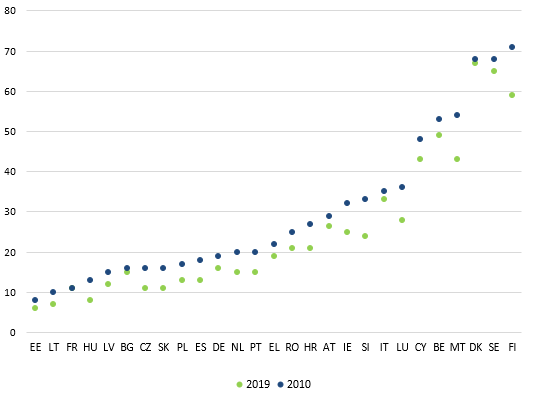

Declining membership poses a challenge to trade unions’ and employers’ organisations’ ongoing role in skills development. Membership and its changes over time remain key to assessing trade unions’ and employer organisations’ strength. Trade union membership is declining in all Member States (Chart 3.13). (377) The drop is particularly notable in Finland (-12 pp) and Malta (-11 pp). The rapidly changing labour market environment, together with increases in non-standard work, migration, and labour mobility, all pose challenges to trade unions’ ability to attract and successfully represent workers in those groups. (378) Membership of employers’ organisations has remained stable in most of the Member States for which data are available.

Chart 3.13

Trade union membership rate declined in all Member States in the last decade

Net union membership as a proportion of wage and salary earners in employment, 2010-2019

Note: Latest available data from 2019, 2018 (Hungary, Czechia, Latvia, Romania, Slovakia), 2017 (Poland), 2016 (Bulgaria, Cyprus, France, Greece, Portugal), 2015 (Slovenia).

Source: OECD/AIAS database on Institutional Characteristics of Trade Unions, Wage Setting, State Intervention and Social Pacts (ICTWSS) 2021.

Promoting collective bargaining remains important to tackling labour and skills shortages, including by improving working conditions. Collective bargaining helps to attract new workers by improving employment conditions in a sector, contributing to more adequate minimum wage protection and general wage development. (379) For example, in Slovenia, the collective agreement in the paper industry sets a higher basic wage, making employment in the sector more attractive. Beyond actual wage increases, the Slovenian example is particularly innovative in that unions and employers agreed to work together to improve the sector’s image. Collective bargaining also helps to retain workers by enabling them to acquire new skills, as in the motor vehicle manufacturing sector in the Netherlands. (380)

The collective bargaining coverage rate is decreasing for most Member States. (381) According to the Structure of Earnings Survey (SES), during the period 2010-2018, the collective agreement coverage significantly decreased for all sectors at NACE 2-digit level. However, in 2018, the difference in coverage rates did not significantly differ between the group of sectors that did/did not experience shortages (1 pp difference). Within the group of sectors experiencing shortages, some recorded a significantly higher share of workers not covered by an agreement at any level (national/industry/individual/local). This group includes architectural and engineering activities, ICT, and manufacture of fabricated metal products and furniture.

At national level, social partners are well placed to design training and support Member States to strengthen the links between learning and labour market needs. In some countries, social partners are key stakeholders in designing measures to increase the labour market relevance of VET systems. Reform of those systems ideally needs to be aligned with labour market changes and respond to rapidly changing labour market demands. The involvement of social partners may ensure that the skillsets embodied in the training systems reflect real occupational needs. (382) Effective dialogue among social partners, PES, chambers of commerce, and governments is crucial in providing relevant labour market information, support, and training. In Portugal, the PES and social partners co-manage a network of 24 training centres. (383) In Denmark, adult vocational training (AMU) was established to provide an adequate response to labour market needs. AMU learning programmes are developed through tripartite agreements with social partners, which decide the learning outcomes and forms of assessment. (384) In the Netherlands, the Foundation for Cooperation on VET and the Labour Market facilitates interactions between different stakeholders involved in VET. (385) (386) The Foundation is responsible for keeping sectoral VET qualifications up to date and it advises the government on skill needs, qualifications, and examination structures. Similarly in Sweden, social partners play an active role in shaping training programmes. (387) However, their impact on policies varies across Member States, with some, such as Poland, reporting a decline in the quality of their involvement in social dialogue.

European cross-industry social partners acknowledge skills challenges and translate them into new priorities for the future. The 2022-2024 cross-industry work programme of the European social partners underlines the importance of a skilled workforce as one of the main assets of the European social and economic model. (388) The 2020 Framework Agreement on Digitalisation, agreed between European cross-industry social partners, encourages social partners to devise common strategies to respond to the digital transformation and commits trade unions and employers to promoting reskilling and upskilling. (389) (390)

Across the EU, sectoral social partners have identified activities to develop skills in some key shortage sectors. Projects for skills identification and development have been initiated in the social services sector and the electricity sector. (391) Social partners in the healthcare sector presented a framework of action to tackle labour shortages and qualification needs. (392) In the chemical, pharmaceutical, plastics and rubber industries sectors, social partners thoroughly analysed digital skills needs and adopted relevant curricula and frameworks for digital skills and competences. (393) In the education sector, social partners work together on recommendations to support life-long learning and to identify challenges, including in the context of digitalisation. (394) With the support of the European Commission, social partners implement multiple projects to promote quality and inclusive VET, upskilling and reskilling of professionals and managers, and skills for the green and digital transitions. (395) In Spain, the government and social partners signed the Agreement for Economic Reactivation and Employment, which aims to develop effective mechanisms for digital training and boost the green transition in all sectors. (396)

In the context of demographic challenges and labour shortages, social partners support the integration of refugees and other migrants into the labour market. Business representatives have suggested prioritising the recognition of qualifications and skills assessment tools for third-country nationals. (397) In 2020, some organisations committed to further efforts in the protection and integration of migrants by strengthening existing integration networks. (398) At the end of 2022, the European Commission and European social and economic partners jointly reaffirmed their renewed commitment to the European Partnership for Integration, underlying the importance of integrating refugees and migrants effectively in the European labour market. (399) The cross-industry social partners worked closely together with the European Commission to develop a Talent Pool pilot (400) to help those fleeing the war in Ukraine to integrate into the EU labour market.

Box 3.11: Measures to improve employment and working conditions at EU and national level

At EU level, regulations and policy initiatives have been introduced to limit or decrease exposure to demanding working conditions and promote access to more favorable and fairer working conditions regardless of employment status, as stipulated by the European Pillar of Social Rights . The analysis confirms the ongoing importance of a number of EU legislative initiatives on health and safety at work such as to address the occupational health and safety risks of workers including their exposure to carcinogens, improving the physical demands of the working environment and preventing violence and psychosocial risks at work, as well as promoting gender equality and fair remuneration (see Chapter 2, section 7).

The EU has introduced numerous initiatives and regulations to ensure fairer working conditions and quality jobs. Directive 2019/1151 on transparent and predictable working conditions introduced measures to prevent abusive practices in the use of on-demand and similar employment contracts. Recently, Directive 2022/2041 seeks to improve the adequacy of minimum wages and strengthen collective bargaining, so as to ensure fair wages and a decent standard of living for workers (based on a full-time employment relationship), with legislative proposals to improve the employment conditions of platform workers and protect workers from the risks related to the exposure of carcinogens at work.

At national level, a recent report (1) found that in the healthcare and long-term care sectors, measures in certain EU countries to address labour shortages have focused on wages and working conditions as a way of improving the attractiveness of these sectors. By contrast, in the ICT sector, where wages and working conditions on average tend to be more favourable, policy measures have focused on skills: identifying current and future skills needs in ICT, developing curricula that match employers’ requirements, and delivering training to a variety of target groups. In addition, measures also aim to attract labour to the ICT sector, in particular from underrepresented groups, such as women.

- 1. Eurofound (2023).

At EU level, new initiatives underline the importance of social partners in fostering better working conditions, ensuring adequate wages, and tackling skills shortages. In January 2023, the European Commission proposed a Council Recommendation to strengthen social dialogue at national level, (401) and adopted a Communication on reinforcing social dialogue at EU level. These documents emphasised the importance of an enabling environment for bipartite and tripartite social dialogue, which can contribute to new or existing labour protection policies, such as the right to disconnect from work or protection against violence and harassment at work (Box 3.11). Recommendations include promoting higher coverage of collective bargaining at all appropriate levels, consultation and involvement of social partners in policy-making, and strengthening their capacity. The recently adopted European Commission Communication on harnessing talent in Europe’s regions also acknowledges the need to enhance social partners’ involvement in regions facing a talent development trap, (402) given the value they add to improving working conditions, wages, and skills and labour shortages.

Notes

- 373. (International Labour Office, 2022).

- 374. (Heyes and Rainbird, 2011).

- 375. (European Commission, 2019b).

- 376. (Eurofound and Cedefop, 2020).

- 377. OECD and AIAS (2021), available here.

- 378. (European Commission, 2016b).

- 379. (European Commission, 2023a).

- 380. (Eurofound, 2022).

- 381. OECD and AIAS (2021), available here.

- 382.(OECD, 2022a).

- 383. PES Network Stakeholder Conference (2022), available here.

- 384. (Cedefop, 2022d)

- 385. Samenwerking Beroepsonderwijs Bedrijfsleven (SBB).

- 386. (OECD, 2022a).

- 387. (Kuczera and Jeon, 2019).

- 388. European Social Dialogue Work Programme 2022-2024, available here.

- 389. (European Trade Union Confederation (ETUC) et al., 2020).

- 390. (Eurofound, 2021).

- 391. Federation of European Social Employers' projects available here.

- 392. (HOSPEEM-EPSU, 2022).

- 393. Social partners in the graphics sector designed a skills-related project targeting the younger generation, ‘Print Your Future’, available here.

- 394. Joint European Union Trade Union Committee for Education (ETUCE) and European Federation of Explosives Engineers (EFEE) statement on opportunities and challenges of digitalisation for the education sector (December 2021), available here.

- 395. DG EMPL database of projects.

- 396. (Eurofound, 2020)

- 397. (SME United, 2023)

- 398. ETUC Resolution for the integration of migrants and the consolidation of the UnionMigrantNet available here; ETUC Resolution on avenues of work for the ETUC in migration and asylum fields (2019-2023) available here.

- 399. Joint statement by the European Commission and Economic and Social Partners on a renewal of the European Partnership for Integration available here.

- 400. Accessible from the EURES website here.

- 401. Proposal for a Council Recommendation on strengthening social dialogue in the European Union available here.

- 400. The talent development trap occurs in regions with insufficient numbers of skilled workers and university and higher-education graduates to offset the impact of the declining working age population due to depopulation and an ageing population.