5. Labour shortages in a gender-segregated economy

Gender segregation contributes to persistent labour shortages to the extent that it hampers efficient functioning of the labour market. (215) There are two key channels in which labour market efficiency can be impaired. Firstly, the efficiency with which available workers are allocated to jobs that best match their skills and talents can be reduced by discrimination in hiring, pay and promotions, specific aspects of working conditions (such as availability of the flexible working arrangements important for work-life balance) or undervaluation of certain types of jobs (such as care work) and expectations about who works in them. Secondly, gender segregation can affect the current and future supply of certain skills in ways that make suboptimal use of women’s and men’s talents. Segregation in different fields of education is of paramount importance. It tends to start early in life, when children first encounter gender stereotypes signalling that some subjects are typically male and some typically female, for example in educational materials, or through teacher/parent perceptions. Such stereotypes are not grounded in (or exaggerate) gender differences in early educational outcomes, (216) but nevertheless affect children’s long-term aspirations and self-confidence, contributing to stereotypical subject choices irrespective of individual ability. For example, girls with similar scientific and mathematical achievements to boys enter STEM studies considerably less often. (217) Together, these factors can result in labour markets where many occupations and sectors are dominated by either men or women, with limited efforts to use and/or develop labour supply from the underrepresented gender. This limits the pool of people available to fill new vacancies in times of rising demand, making certain jobs more prone to persistent labour shortages.

The EU labour market is heavily gender segregated across occupations and economic activities. (218) In 2021, fewer than one in four occupations were gender balanced, (218) accounting for less than one-fifth of the overall EU workforce. Almost 4 in 10 workers in the EU worked in an occupation where one gender accounted for more than 80% of all workers. Aggregate measures of gender segregation (220) by occupation imply that roughly every second man or woman would need to change occupation (e.g. more men becoming nursing professionals rather than ICT specialists, and vice versa for women) if all occupations were to become perfectly gender balanced. The picture was similar across sectors and subsectors of the EU economy – less than one-third of subsectors were gender balanced in 2021, comprising about one-quarter of the EU workforce.

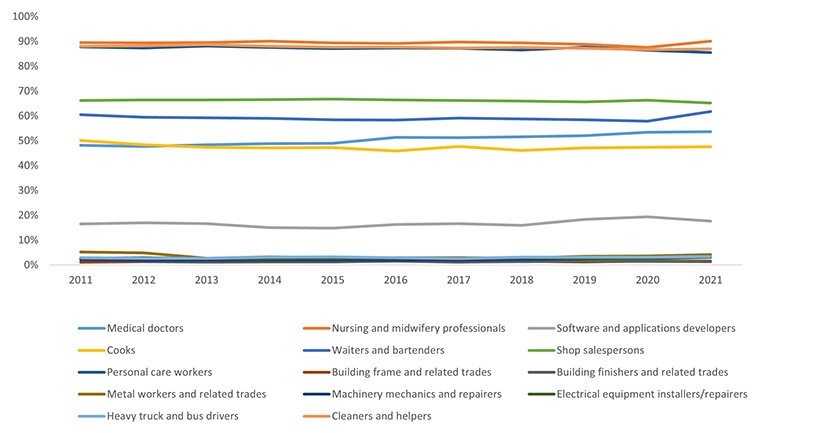

Chart 2.16

Low shares of women in shortage sectors

Proportion of women in shortage sectors (% of all workers in a given sector), 2021, EU-27

Source: EU-LFS 2021.

Historically, increases in women’s activity rates have led to increases in their employment rates, but without substantially changing existing patterns of gender segregation in the EU labour market. Around 82% of the increase in the employment of women since 2011 happened along existing patterns of gender segregation, i.e. without changing the 2011 shares of women in different occupations. The last two decades have seen little change in existing aggregate measures of gender segregation across occupations. (221)

5.1. Gender segregation in sectors and occupations with labour shortages

In the EU, persistent labour shortages are more common in economic activities with low shares of women workers. Most of the sectoral labour shortages common across the Member States (see section 2.1.) are in male-dominated activities, including: computer programming, consultancy and related activities; civil engineering; land transport; several construction and manufacturing activities; repair and installation of machinery and equipment; and security and investigation (Chart 2.16). Women account for most workers in three shortage sectors: health, residential care and social work. In 2021, only 2 out of 16 shortage sectors were gender balanced (manufacture of textiles, and building and landscape services).

Around half of all occupations showing persistent labour shortages across the Member States are male-dominated (Chart 2.17). Shortage occupations where men accounted for more than 80% of workers in 2021 included several STEM occupations (civil engineers, highly skilled ICT occupations), several specialist construction occupations, machinery mechanics and repairers, electrical equipment installers and repairers, and heavy truck and lorry drivers.

Chart 2.17

Most shortage occupations are segregated by gender

Proportion of women in shortage occupations (% of all workers in a given occupation), 2011-2021, EU

Note: Analysis based on all Member States where occupational statistics are available at ISCO-08 3-digit level, i.e. excluding Bulgaria, Malta and Slovenia.

Source: EU-LFS 2011-2021.

Conversely, three occupations characterised by persistent labour shortages are jobs in which women account for more than four-fifths of workers. These are nursing and midwifery professionals, personal care workers, and domestic and office cleaners. Gender representation is approximately balanced in only two of the shortage occupations ‒ medical doctors and cooks. For doctors, recent evidence points towards segregation by specialty (e.g. in paediatrics or surgery) in high-income countries. (222)

Gender segregation in occupations facing persistent labour shortages has not changed over time Where either women or men accounted for more than 80% of all workers in an occupation in 2011, this was also the case in 2021, with little or no change in the gender composition of the relevant workforce. This implies that in the absence of measures to tackle gender segregation, increases in women’s labour market participation will address labour shortages only in occupations where women already account for substantial shares of all workers.

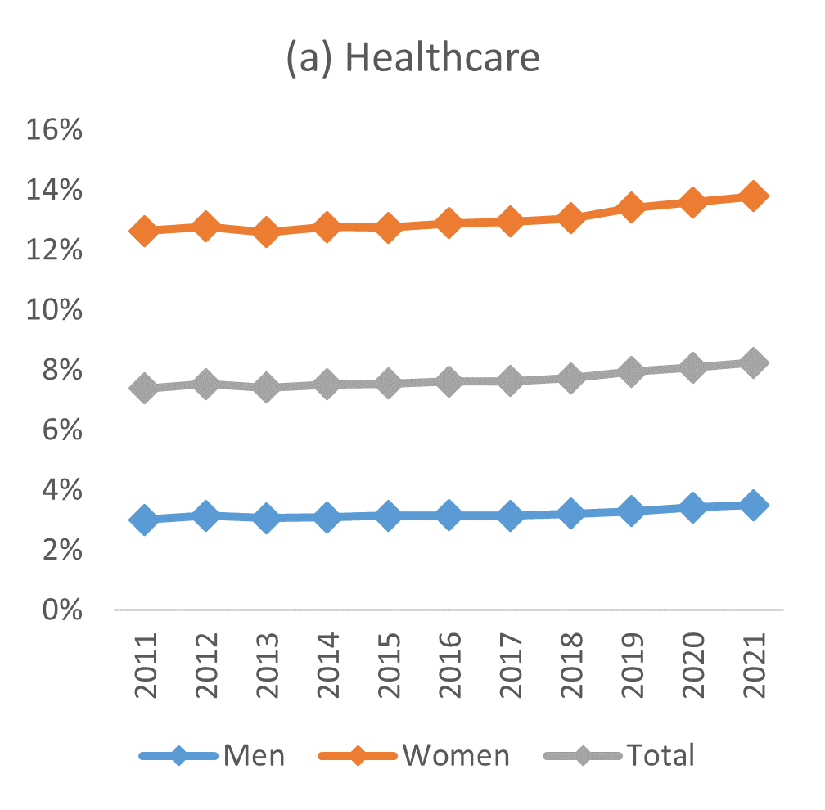

Chart 2.18

Persistent gender segregation in STEM and healthcare occupations

Proportion of workers in STEM and healthcare occupations, by gender, EU

Note: Analysis based on all Member States where occupational statistics are available at ISCO-08 2-digit level, i.e. excluding Malta.

Source: EU-LFS 2011-2021.

5.2. Gender segregation in skilled STEM and healthcare occupations facing shortages

Reducing gender segregation in skilled occupations characterised by persistent labour shortages offers a significant opportunity to attract additional talent. In order for this to happen, the key factors contributing to underrepresentation of either men or women in these occupations must be addressed. This section focuses on factors that lead to segregation in two broader occupational groups known to contain skilled occupations facing shortages: STEM and healthcare. Not only are these two groups already facing labour shortages, they are also projected to see employment demand expand substantially in the coming years (see section 2.1.), making efforts to attract additional talent ever-more pressing.

STEM and healthcare occupations remain gender segregated despite persistent labour shortages. At EU level, in 2021, around 15% of all male workers were employed in STEM occupations, compared to about 5% of all female workers, leading to a gender STEM gap of about 10 pp (Chart 2.18). A similar gender gap can be observed in healthcare occupations, in this case with women as the overrepresented gender ‒ around 14% of all female workers were employed in healthcare occupations in 2021, compared to about 3% of all male workers. While the overall share of employment in STEM and healthcare occupations grew slightly since 2011, the gender gap remained broadly the same in both occupational groups.

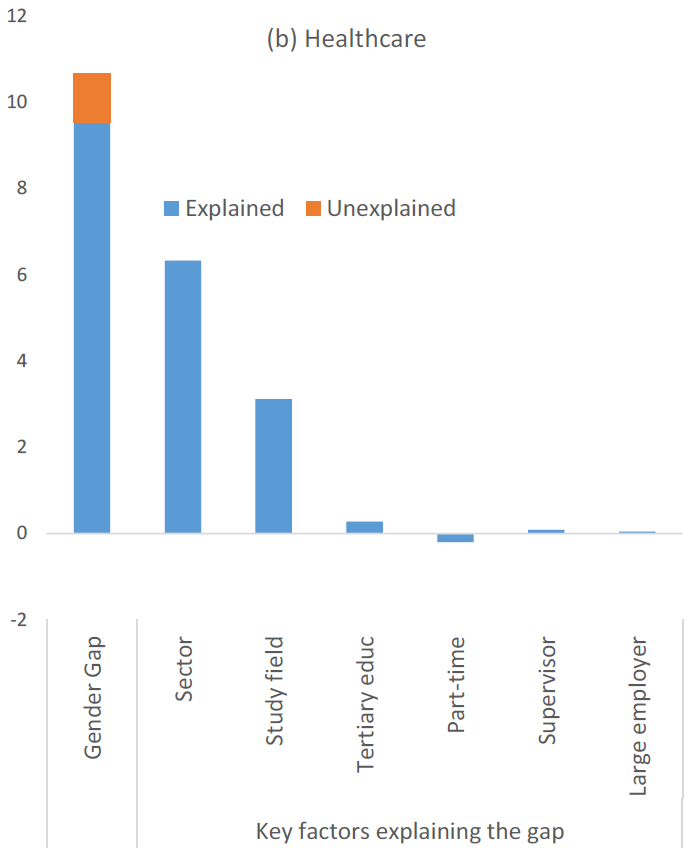

Chart 2.19

Gender gaps in STEM and healthcare are explained by gender differences in fields of education and economic activity

Gender gaps in STEM and healthcare occupations, by contributing factors (pp), workers aged 20-64, 2021, EU

Note: Analysis based on all Member States where occupational statistics are available at ISCO-08 2-digit level, i.e. excluding Malta. The available data distinguish education by study field and ISCED level, but do not distinguish between types of education (e.g. post-secondary vocational vs university tertiary education).

Source: EU-LFS 2021.

Several factors contribute to persistent gender segregation in STEM and healthcare work. Gender segregation in relevant educational fields is crucial. (223) Women account for about one in four tertiary education graduates in engineering, manufacturing and construction, and one in five graduates in ICT, (224) but more than two-thirds of tertiary education graduates in health. Similar patterns can be observed in VET. (225) Various gender stereotypes contribute to gender segregation in both STEM and healthcare from early in life. For example, stereotypes in teachers’ perceptions or depictions of engineers or nurses in school textbooks help to shape children’s future work aspirations. (226) Other factors are more specific to the area. For example, the underrepresentation of women in STEM is linked to the gender divide in advanced digital skills, masculine organisational cultures in some workplaces, and a lack of work-life balance options and role models in certain STEM fields. (227) In healthcare, women particularly dominate occupations that can be linked to their expected roles as unpaid caregivers in society, (228) such as nurses or personal care workers. Given this link to unpaid care, these occupations are often undervalued in status, working conditions and salary. By contrast, some well-paid, high-status healthcare professions associated with technical skills, such as surgery, tend to be performed primarily by men. (229)

Differences in study fields of qualifications (230) held by women and men explain large shares of gender gaps in STEM and, to a lesser extent, healthcare occupations (Chart 2.19). (231) They account for almost half of the underrepresentation of women in STEM and about one-third of underrepresentation of men in healthcare at EU level, with considerable variation across Member States. (232) This reflects the high skill and knowledge intensity of STEM and healthcare work. In 2021, almost two-thirds of workers in STEM occupations held tertiary qualifications, with men holding most of the qualifications directly relevant to STEM work. For example, around 10% of all male workers in the EU achieved a tertiary qualification in engineering, manufacturing and construction, while a further 3% held an ICT qualification. Corresponding proportions for female workers were much lower, at 3% and 1%, respectively. Similar but less pronounced patterns applied to healthcare workers in 2021 ‒ about half were tertiary educated, with women holding the majority of healthcare-related qualifications.

The fact that women and men tend to work in different sectors accounts for much of the remaining gender gap in STEM and healthcare occupations. The drivers of gender segregation outlined at the beginning of this section often operate at sectoral, as well as occupational, level. This includes broader gender norms and stereotypes around work in certain sectors, (233) sectoral differences in remuneration, (234) and sector-specific aspects of working conditions (e.g. option to combine work with unpaid childcare) or work culture. (235) For example, gender segregation in healthcare occupations tends to be far more pronounced in the female-dominated healthcare sector (8 out of 10 workers in healthcare occupations in the EU are women) than in the more gender-balanced professional, scientific and technical activities (where healthcare occupations employ roughly as many men as women).

Chart 2.20

Higher probability of working in STEM or healthcare for women and men with relevant qualifications

Predicted changes in probability of working in healthcare and STEM occupations, by selected worker and job characteristics (pp), workers aged 20-64, 2021, EU

Note: Analysis based on all Member States where occupational statistics are available at ISCO-08 2-digit level, i.e. excluding Malta. Data distinguish education by study field and ISCED level, but do not distinguish between types of education (e.g. post-secondary vocational vs university tertiary education).

Source: EU-LFS 2021.

Holding relevant qualifications increases the likelihood of working in STEM or healthcare occupations for both women and men, but this effect tends to be stronger for the dominant gender (Chart 2.20). For men, holding an ICT qualification increases the chance of working in STEM occupations by almost 30 pp, (236) compared to less than 20 pp for women. (237) A similar, albeit weaker, pattern can be observed for healthcare qualifications, which increase a woman’s chances of working in a healthcare occupation by 22 pp, compared to 19 pp for men.

For men, the probability of working in STEM occupations also increases with achieving at least a secondary generic (238) qualification and with the level of achieved qualification (regardless of field) Men holding at least an upper secondary generic qualification are almost 9 pp more likely to work in STEM occupations than those who did not complete upper secondary education, and the probability increase is even sharper for those holding any tertiary qualification (by about 17 pp). For women, the corresponding increases are far smaller, at less than 5 pp.

Notes

- 215. (European Commission, 2009), (EIGE, 2018).

- 216. For recent studies discussing gender differences in maths performance, see e.g. (Bertoletti et al., 2023a) and (Bertoletti et al., 2023b).

- 217. See, for example, (EIGE, 2018).

- 218. (EIGE, 2018), (Eurofound and Joint Research Centre , 2021), (Mariscal-De-Gante et al., 2023). Gender segregation by occupation is a fairly widespread problem that also occurs frequently in non-EU countries, as shown in a recent study by the World Bank (Das and Kotikula, 2019).

- 219. Occupations with 40-60% of each gender are considered gender-balanced. Occupations are taken at ISCO-08 3-digit level. The analysis is based on all Member States where occupational statistics at this level are available, i.e. excluding Bulgaria, Malta and Slovenia.

- 220. Gender segregation is captured by the Duncan dissimilarity index (see (Eurofound and Joint Research Centre , 2021)).

- 221. (Eurofound and Joint Research Centre , 2021).

- 222. (Pelley and Carnes, 2020), (World Health Organisation, 2019).

- 223. (McNally, 2020), (EIGE, 2020a), (European Parliament, 2015).

- 224. Eurostat educ_uoe_grad02.

- 225. (European Commission, 2022d).

- 226. See, for example, (Thebaud and Charles, 2018) for a detailed discussion of how stereotypes contribute to segregation of STEM work.

- 227. (EIGE, 2020b).

- 228. (Shannon et al., 2019), (World Health Organisation, 2019).

- 229. (EIGE, 2018), (World Health Organisation, 2019).

- 230. Analysis controls for the following broad fields of education in respect of (at least) secondary qualifications: generic programmes and qualifications; education; arts and humanities; social sciences, journalism and information; business, administration and law; natural sciences, mathematics and statistics; ICT; engineering, manufacturing and construction; agriculture, forestry, fisheries and veterinary; health and welfare; services.

- 231. For details on analytical methodology, see (European Commission, 2023i). The results of this analysis need to be read with caution, as considerable data limitations affect the robustness of analysis. The data do not directly capture a number of factors identified as important contributors to occupational gender segregation, such as certain important working conditions (e.g. pay), unpaid childcare obligations, or certain gender norms and stereotypes.

- 232. For details on variation by Member State, see (European Commission, 2023i).

- 233. See, for example, (Thebaud and Charles, 2018) for a detailed discussion of role of stereotypes in STEM sectors.

- 234. For example, declining wages in the health sector have been associated with the increasing proportion of women in this sector in high-income countries (Shannon et al., 2019). There also appears to be a sizeable gender pay gap in the health sector, indicating that men tend to enter in better paid positions (Boniol et al., 2019), (EIGE, 2018).

- 235. (EIGE, 2020a).

- 236. Compared to workers with lower educational achievement (ISCED 0-2).

- 237. This corroborates existing evidence showing that achieving a tertiary qualification in a STEM-related field improves men’s chances of working in that field more than women (EIGE, 2018).

- 238. This includes basic programmes and qualifications, literacy and numeracy, personal skills and development, and other generic programmes and qualifications not further defined.