3. Assessment of policies to address skill shortages and improve matching

3.3. What works and for whom? Training programmes to help address skills shortages

Training programmes are key to addressing skills shortages by enabling upskilling and reskilling throughout the working life. Policies that better align skills demand and supply by training jobseekers or people at risk of unemployment can help to address labour and skills shortages. It is important, therefore, to ensure that training provision is tied to skills demands in the labour market.

Counterfactual impact evaluations can improve the effectiveness of training design. A 2023 European Commission report (340) emphasised that the effectiveness of training measures should always be evaluated, including their long-term impact. (341) Evaluations of training frequently focus on the effects of programmes on employment outcomes, with some also looking at additional outcomes such as earnings, occupational mobility, health, and social inclusion. Recently, the European Commission published a synthesis of individual ESF and Youth Employment Initiative (YEI) counterfactual impact evaluations in the Member States in the 2007-2013 and 2014-2020 programming periods. (342) Overall, it found that ESF and YEI interventions in the EU are effective, with around 40% of estimates for training programmes (343) having significant positive effects on employment outcomes, and the average effect sizes of training programmes increasing over time. (344) This section presents the findings of counterfactual impact evaluations of training programmes in Lithuania and Finland, carried out in the context of a joint OECD-European Commission project (Box 3.6). (345)

Box 3.6: OECD-European Commission joint project on counterfactual impact evaluation

Between 2020 and 2024, the OECD and the European Commission are undertaking a joint project on counterfactual impact evaluation through the use of linked administrative and survey data. Within the context of the project, vocational training programmes in Lithuania and Finland have been evaluated,focusing on employment, earnings, and occupational mobility outcomes. Overall, the project has a dual aim:to improve the effectiveness of active labour market policies (ALMPs) based on the results of the counterfactual impact evaluations; and to strengthen the countries’ capacity for evidence-based policy-making. It builds on previous European Commission work, including guidelines for advanced counterfactual impact evaluation methods and tailored guidelines for national authorities evaluating the impact of the ESF. (1)

Countries employ a variety of ALMPs to address gaps in labour market opportunities and improve jobseekers’ employability. Accurately evaluating these policies can help to identify what works and for whom. Counterfactual impact evaluations can provide reliable evidence on the causal impacts of training programmes. Experimental approaches are often considered when evaluating the impact of a policy or programme, as entities are randomly assigned to the treatment and control groups. In situations where it is not possible to conduct randomised control trials, quasi-experimental counterfactual impact evaluations can mimic the process of randomisation by constructing a control group that is as close as possible to the treatment group, in order to isolate the causal effects of training on labour market outcomes.

Evaluations ‒ particularly counterfactual impact evaluations ‒ provide valuable information for making informed policy choices, establishing the accountability of public expenditure, and building support for continued deployment of measures in the longer-term. A key requirement for such evaluations is the use of rich data of good quality, which can be obtained by linking different registers, or through surveys.

- 1. European Commission (2019a); European Commission (2020c); European Commission (2020e).

In Lithuania, employer involvement in the vocational training programme was associated with more positive employment effects. (346) Individuals can participate in voucher-based training through agreement with the PES or through a tripartite agreement involving a future employer. The evaluation, in the context of the OECD-European Commission project, found that the programme had a positive effect on employment and income after nine months, and that it persisted after three years. More positive effects were found for jobseekers with an employer agreement, suggesting a favourable role of employer involvement. In Lithuania, employers can choose the vocational training programmes individuals undertake, provided they have made a commitment to hire the individuals on completion of their training. The report highlights that employer involvement is favourable not only in terms of employment outcomes but also in potentially helping employers to address local skills shortages. The evaluation found that persistent negative effects of vocational training on occupational mobility (347) – which analyses the occupations that individuals enter into constructed as a ‘job ladder’ - were recorded for those aged 30-50. However, positive effects were recorded for women aged 30-50, while jobseekers under 30 years of age were also found to experience upward occupational mobility.

The voucher system allows Lithuania to offer a large selection of training programmes, with a lower administrative burden. The evaluation found that the voucher system could play a role in helping to address local skills shortages more quickly and effectively. Within the system, jobseekers could select from accredited training providers and many different programmes, with the duration of training lasting an average of 2.8 months. The OECD report highlighted that in the 2014-2020 period, jobseekers enrolled in 2 000 different types of courses, with vouchers offering a quick and versatile means of addressing skills demands. The evaluation also found particularly strong positive employment effects of training among women over 50 and among participants with lower skills levels (Chart 3.10).

Chart 3.10

Strong positive employment effects of vocational training for certain subgroups in Lithuania

Percentage point change in employment probability at 24 months (%), by gender, age, skill level

Source: OECD (2022c).

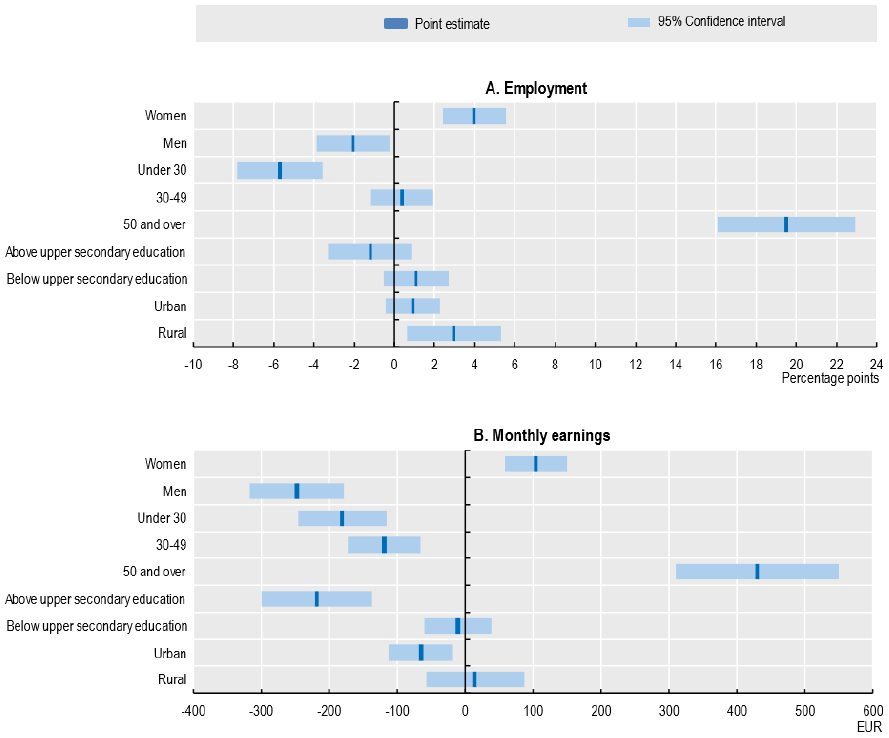

In Finland, both self-motivated training (SMT) and short-term labour market training (LMT) programmes were found to have a positive effect on employment, with longer LMT courses proving more effective. (348) The evaluation addressed the two main types of training ‒ SMT and LMT programmes – offered to jobseekers. (349) SMT was found to have a small positive effect on employment three years after the start of the programme and LMT after two years, with no positive effects for earnings, on average. However, positive impacts on earnings were found for certain subgroups, notably women and older jobseekers, who exhibited larger gains in employment and income (Chart 3.11). Longer LMT courses were found to be more effective in increasing the likelihood of employment and earnings. For both SMT and LMT, training supported individuals to change occupation, (350) but was not associated with upward occupational mobility overall, although some impacts were found for subgroups. Both types of training resulted in a more equal distribution of occupations, with participants moving towards the middle of the distribution of occupations and the share of low-quality occupations reducing considerably. (351)

Chart 3.11

Positive employment and earning effects of SMT in Finland are particularly strong for women and over-50s

Change in employment probability (%), by jobseeker characteristics (gender, age, and skill level), four years after the first observation

Source: OECD (2023a).

In Finland, the provision of LMT courses is linked to systems for skills assessment and anticipation. Skills assessment and anticipation are important tools for addressing skills shortages in both the short and long term (Box 3.7). Finland has a high share of vacancies in highly skilled occupations – in order to ensure that the provision of training is in line with skills needs, forecasting and the anticipation of local development needs takes place within the PES system and involves local PES offices. The evaluation found that workers in some industries with lower labour shortages are more likely to participate in retraining through vocational training. By contrast, labour shortages exist in the restaurant and construction industries, yet workers still sought to retrain. This may be due to the comparatively poor pay and conditions in these industries. (352)

Box 3.7: Anticipating and assessing skills needs in Estonia

The national Skills Assessment and Anticipation exercise (OSKA) in Estonia provides insights into the integration of systematic information on occupational demand and supply to ensure targeted training courses and education. (1)

Established in 2015 and funded primarily by an ESF grant, OSKA is a system of applied research on the labour and skills required in the country. It reviews past trends at national and sectoral level and assesses how various drivers of change will affect future skills demand in sectors of the economy such as ICT and healthcare. (2)

Within OSKA, analyses are based on labour market and education statistics and are compiled in cooperation with employers, policy makers, and representatives of VET and higher education institutions. OSKA is used systematically by the Estonian Unemployment Insurance Fund (EUIF) to guide the provision of training programmes to prevent unemployment and to provide guidance for employment counsellors referring jobseekers for training. The EUIF also has an Occupational Barometer (based on Finland’s Occupational Barometer), which measures short-term supply and demand in different occupations.

Notes

- 340. (European Commission, 2023j).

- 341. Lock-in effects are common across training programmes and are expected where people are studying to accumulate skills. This accumulation can be significant over time and effects should be studied over the longer term to ensure that benefits are properly captured.

- 342. (European Commission, 2022h).

- 343. These are made up of ‘vocational training’, ‘mentoring’ and ‘other training’. The report found that 20-25% display negative significant effects.

- 344. Previous research highlighted that time horizons are an important factor in the assessment of skills training, with education and training programmes (so-called human capital programmes) found to have more significant impacts two-three years after completion (Card, Domnisoru and Taylor, 2018).

- 345. (OECD, 2020a).

- 346. The (OECD, 2022c) report evaluates a voucher-based training programme for jobseekers, where different courses and accredited training providers can be selected. It can be read here.

- 347. In order to provide a tractable measure of occupational mobility, the analysis relies on an occupational index, which is calculated from observed wages. The analysis maps the occupation of individuals entering employment onto an occupational index, which can be interpreted as a ‘job ladder’.

- 348. (OECD, 2023a).

- 349. SMT allows jobseekers to study degree-level programmes while retaining their unemployment benefits for up to two years; short-term LMTs are vocational courses of shorter duration, with the PES deciding who participates.

- 350. Occupational mobility was analysed by looking at occupational distribution by market value.

- 351. Low-quality occupations are defined in terms of observed wages, based on the occupational index.

- 352. (OECD, 2023a). Limited duration seasonal employment is also more common in certain sectors, such as accommodation and food services and construction (see Chapter 2 Section 7.). In addition, fixed-term employment can constitute a stepping-stone to more permanent contracts, particularly for young people.