7. Employment and working conditions in sectors and occupations with persistent labour shortages

Improved working conditions and quality jobs (Box 2.8) are potential drivers of increased labour force participation but also depend on productivity gains. (258) Employment and working conditions potentially affect the prevalence and extent of labour shortages in certain sectors and occupations, particularly when relevant skillsets and experience are not lacking within the available workforce (see section 3.). More specifically, job quality, employment conditions, and earnings can be relevant supply-side factors in attracting labour to sectors and occupations with persistent labour shortages. (259) Training opportunities can also increase the overall attractiveness of work environments and workers’ potential to grow earnings (see Chapter 3, section 3.3.), as well as improving worker retention and preventing skills mismatches through upskilling and reskilling. Variations in employment and working conditions can be the outcome of multiple factors. Differences across sectors and occupations can result from a country’s production structure, differences in productivity gains and demand for labour, as well as the management practices of organisations and firms. They can also stem from a country’s labour supply, including the characteristics and skills of the available workforce. (260) For example, the COVID-19 crisis amplified poor working conditions and job insecurity in some sectors and occupations, such as healthcare, hospitality, and tourism, and for seasonal workers. This led to a growing share of workers moving away from low-quality jobs (low-paying, less flexible, contact-intensive, physically demanding), with a minor impact on the efficiency of EU labour market matching. (261)

Fair working conditions are anchored in the European Pillar of Social Rights. They cover employment conditions, wages, and health and safety at work, among others. (262) The Pillar states that ‘regardless of the type and duration of the employment relationship, workers have the right to fair and equal treatment regarding working conditions’, adding that ‘employment relationships that lead to precarious working conditions shall be prevented, including by prohibiting abuse of atypical contracts’. In addition, it stresses that ‘workers have the right to a high level of protection of their health and safety at work’.

Definitions of working conditions vary and can include the physical, organisational, social, and economic dimensions of jobs. Broadly defined, a working condition is a characteristic, or combination of characteristics, of work that can be modified and improved. According to Eurofound, working conditions refer to the conditions in and under which work is performed, including the organisation of work and work activities, training, health, safety and working time. (263) For the ILO, the term also incorporates the economic dimension of work and its effects on living conditions. (264) While not always included in definitions of working conditions, (265) wages are correlated with workers’ well-being and are widely considered a marker of job quality. The OECD’s Job Quality Framework focuses on the measurement and assessment of job quality and encompasses three dimensions: earnings quality, labour market security, and quality of working environment. (266) Using OECD methodology to capture non-economic aspects of jobs, Eurofound’s job quality indicator focuses on six dimensions, including working time arrangements and the nature and content of work (Box 2.8).

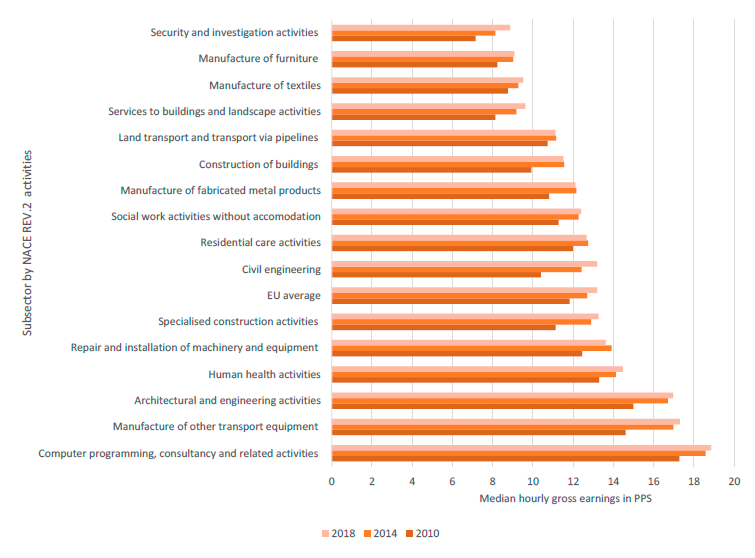

Chart 2.26

Subsectors with persistent labour shortages had both above and below EU average median gross hourly earnings

Median gross hourly earnings (PPS), by subsectors with persistent labour shortages, 2010-2018, NACE 2-digit level, EU-27

Note: Size classes in number of employees is for 10 employees or more.

Source: EU-LFS 2021.

In 2018, substantial differences in median gross hourly earnings were recorded across subsectors with persistent labour shortages in the EU. (267) For nearly two-thirds (10 out of 16) of subsectors with persistent labour shortages, the median gross hourly earnings (268) expressed in purchasing power standard (PPS) (269) were below the EU average of 13.2. Security and investigation activities (8.9), and manufacture of furniture (9.1) and textiles (9.5) recorded well below average earnings. By contrast, computer programming, consultancy and related activities (18.9), manufacture of other transport equipment (17.3) and architectural and engineering activities (17.0) had far higher than average median hourly gross earnings (Chart 2.26)(Chart 2.26). (270) Between 2010 and 2018, the largest increases in median gross hourly earnings were recorded for civil engineering (27%) and security and investigation services (24%), while increases were far lower for land transport and transport via pipelines (4%) and residential care activities (6%).

Almost half of the subsectors facing persistent labour shortages recorded an above-average share of low-wage earners (7 out of 16). In 2018, the proportion of low-wage earners (i.e. those earning two-thirds or less of the national median gross hourly earnings) varied significantly across shortage subsectors. Many subsectors with lower than average median earnings also had higher than average (15%) shares of low-income earners, in particular for manufacture of textiles (44%) and construction of buildings (26%) (Chart 2.27). (271) However, nearly all subsectors with persistent labour shortages – with the exception of manufacture of furniture and manufacture of fabricated metals – experienced a decrease in the share of low-wage earners between 2010 and 2018.

Chart 2.27

Several subsectors facing persistent labour shortages recorded an above-average share of low-wage earners

Low-wage earners as a proportion of all employees (excluding apprentices), by shortage subsector, 2010-2018, NACE 2-digit level, EU-27

Note: Size classes in number of employees is for 10 employees or more.

Source: Eurostat SES, NACE Rev.2, 2-digit level.

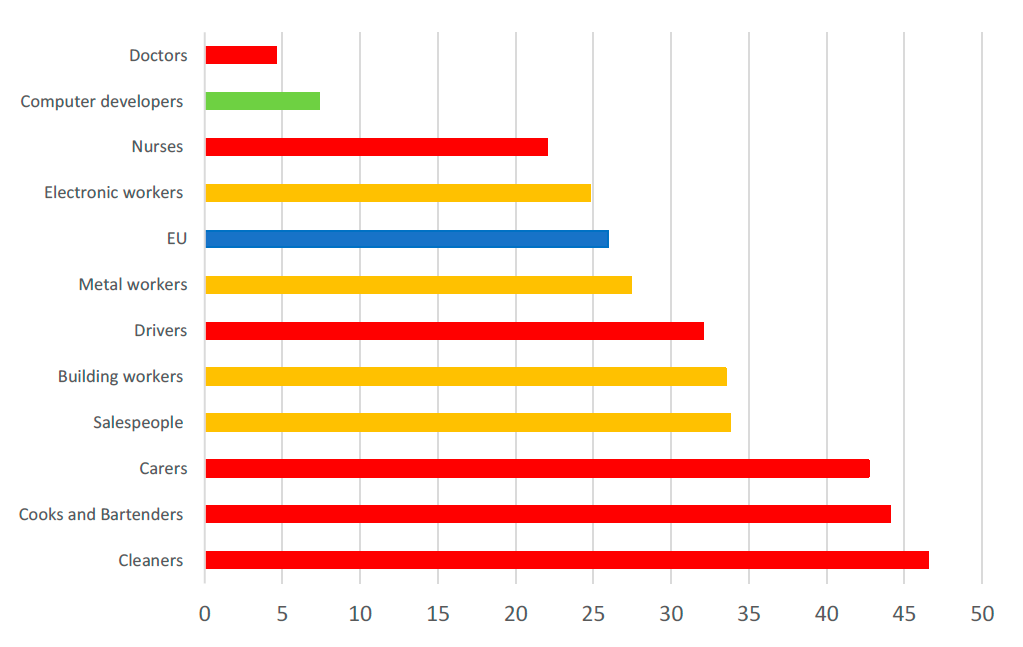

In 2021, several occupations characterised by persistent labour shortages reported an above EU average proportion of workers having difficulties in making ends meet. (272) This was most notable for cleaners (47%), cooks and bartenders (44%), and carers (43%), against the EU average of 26% (Chart 2.28). Only medical doctors (5%) and computer developers (7%) had substantially lower than average shares of workers reporting difficulties in making ends meet. Occupations with persistent labour shortages reporting higher than average difficulties in making ends meet also had higher shares of workers unable to predict their earnings in the next three months, pointing to a link between lower pay and less stable earnings. At least one-quarter of cleaners, building workers, salespeople and cooks reported being unable to tell in advance how much they were going to earn in the next three months. In addition, certain shortage occupations did not believe they were fairly rewarded. For instance, only 40% of nurses felt that they were paid fairly in relation to their efforts and achievements (19 pp lower than the average).

Chart 2.28

Several shortage occupations have above-average difficulties in making ends meet

Proportion of workers in shortage occupations reporting difficulty in making ends meet, 2021, EU-27

Note: Red indicates significantly above EU average job strain, orange indicates slightly above EU average job strain, and green indicates below EU average job strain.

Source: Eurofound, EWCTS 2021.

Workers’ reasons for opting into temporary or solo self-employment are heterogeneous and can be markers of both a desired flexibility and comparatively higher job insecurity. Where job insecurity associated with non-standard forms of employment is indicative of less favourable employment and working conditions, this can make sectors and occupations less attractive for workers and contribute to driving persistent labour shortages. On the one hand, workers may seek out more flexible employment arrangements, and non-standard forms of work (273) can offer such autonomy. Self-employed, including solo self-employed (or ‘own-account’ (274)) workers, can choose to work for multiple clients. Non-standard workers may also see such employment forms as a stepping-stone to more permanent contracts. (275) In addition, more fixed-term forms of employment relationship are common for jobs with a higher rate of seasonal employment, such as those in hospitality and tourism. On the other hand, due to its limited duration, temporary employment ‒ which is by definition fixed-term ‒ can be associated with higher job insecurity, especially when workers do not subsequently move to more stable and permanent jobs. (276) Solo self-employment can also be marked by job insecurity, involve elevated risks of precariousness (277) (not least because in many EU countries it implies more limited access to social protection compared to permanent employment (278)), and may conceal dependent employment relationships and bogus self-employment (279), as well as signalling labour market segmentation within sectors and occupations. A recent European Commission report on the implementation of the 2019 Council Recommendation on access to social protection confirmed that many self-employed workers still face significant gaps in social protection coverage. (280) In 2022, 19 Member States had at least one branch of social protection for which self-employed people were not covered, and, where participation in social protection schemes was voluntary for the self-employed, take-up rates were generally low. Despite offering flexibility and lowering barriers to labour market access for some workers, employment statuses that involve lower job security and elevated risks of precariousness (including due to associated gaps in social protection) can contribute to less favourable employment and working conditions in certain shortage sectors and occupations, in particular where workers do not actively seek them out.

Temporary employment and solo self-employment are common in certain subsectors with persistent labour shortages but far less typical in others. In 2021, the share of temporary employment was substantially higher for social work activities without accommodation (17%) and residential care activities (281) (16%), compared to the EU average (12.1%). By contrast, these shares were lowest for architectural and engineering (7%) and computer programming, consultancy, and related activities (7%). Across shortage subsectors, architectural and engineering activities (20%), specialised construction activities (19%), construction of buildings (13%), and computer programming, consultancy and related activities (11%) recorded above EU average (10.3%) shares of solo self-employed workers. (282)

Box 2.8: Measuring job quality in subsectors and occupations with persistent labour shortages

Job quality is a multidimensional concept that is used to complement job quantity measures, with different actors and disciplines emphasising different dimensions.

Eurofound’s 2021 EWCTS (1) captured six dimensions of job quality: physical and social environment; job tasks; organisational characteristics; working time arrangements; job prospects; and intrinsic job features. The job quality indicator uses a methodology developed by the OECD that compares job demands (which affect workers negatively) and job resources (which affect workers positively). When workers have more demands than resources, they experience poorer job quality or job strain.

The job quality index is positively associated with well-being. (2) The dimensions of work and employment included in the index have been selected for their positive/negative association with health and well-being, as demonstrated in high quality epidemiological prospective studies. Occupation and sector have been identified as important determinants of all job quality indices (3) and variation in job quality indices can be observed across both elements.

Where job strain is reported as high, this suggests that improving job quality in the sectors and occupations experiencing persistent labour shortages could potentially increase their attractiveness and participation rates. Job strain also entails higher risks to health and well-being.

- 1. EWCTS is a Europe-wide probability-based survey conducted between March and November 2021. It was carried out via telephone survey, unlike the previous 2015 European Working Conditions Survey (EWCS), which used face-to-face interviews. Data collection for the EWCTS took place when the specific demands of the COVID-19 pandemic may still have had an effect on jobs.

- 2. (OECD, 2022d).

- 3. (Eurofound, 2021).

Dependent self-employment is highest in the construction and human health and social work sectors, and comparatively low in the ICT sector. (283) With self-employed workers constituting a heterogeneous group of workers overall, their economic and organisational dependency are factors that are useful in assessing the boundaries between employment and self-employment. Across shortage sectors, the largest share (17%) of dependent self-employed workers without employees is in construction, followed by human health and social work activities (11%). Professional, scientific, and technical activities contain a substantial share of both dependent (10%) and independent (13%) self-employed people, with ICT (7%) recording a lower share of dependent self-employed workers. (284)

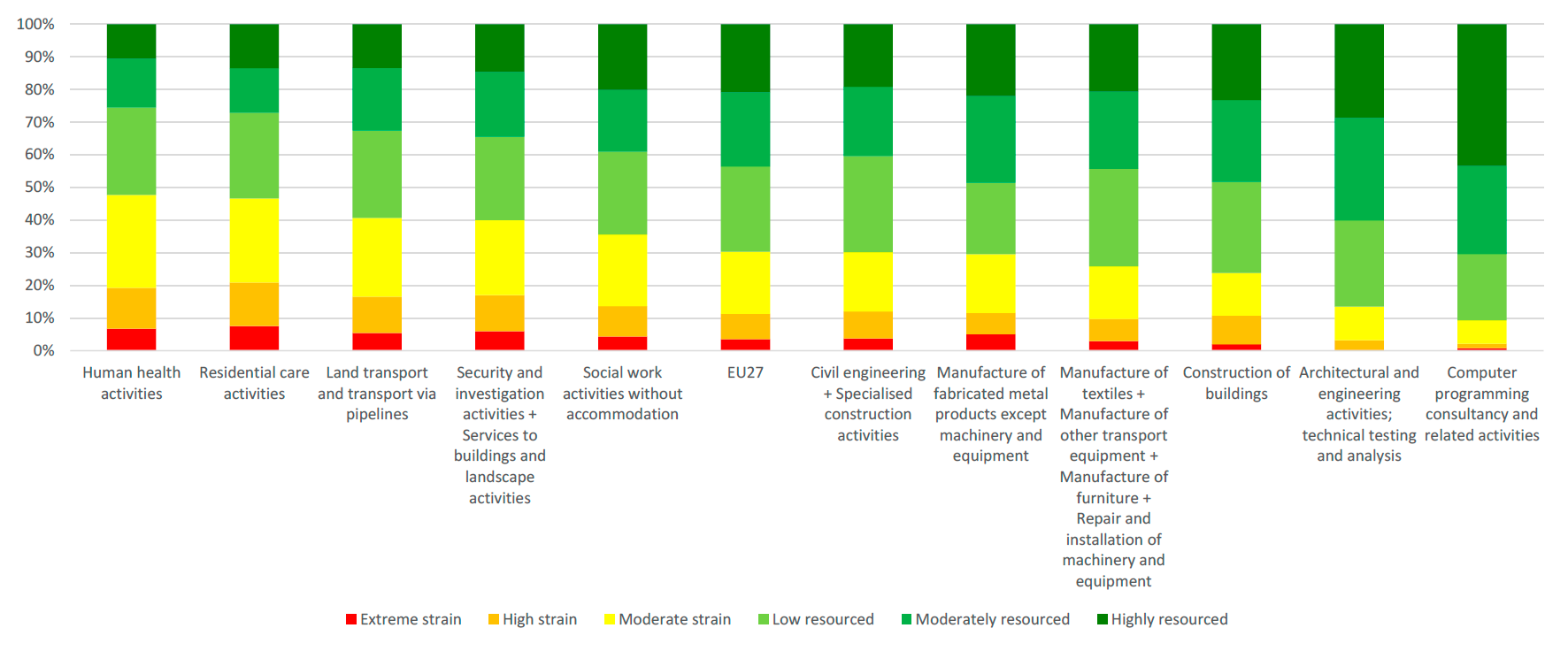

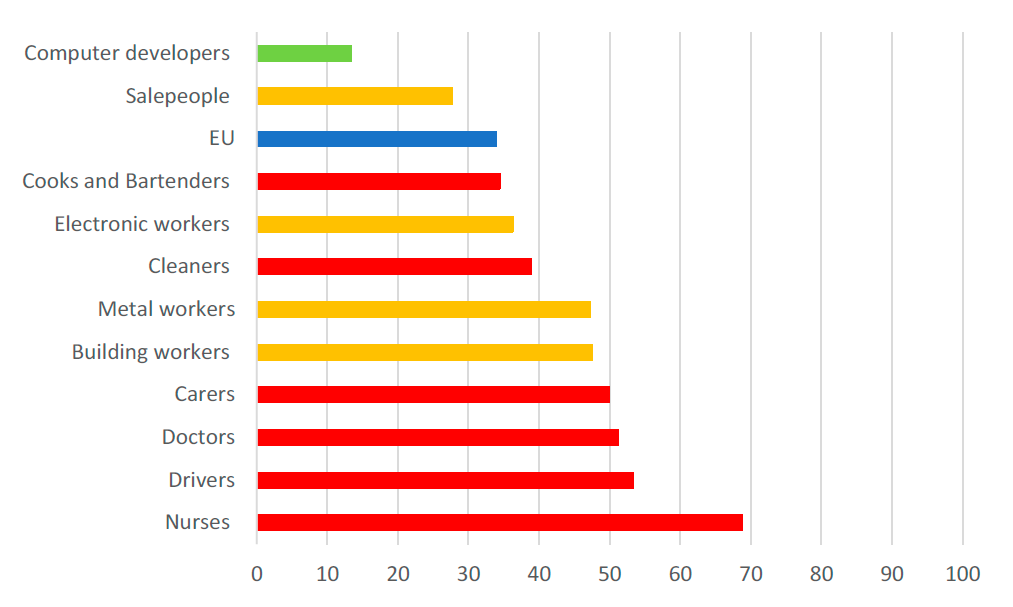

In 2021, workers reported high levels of job strain in some sectors and occupations characterised by persistent labour shortages (Chart 2.29). This was particularly evident in the health (48%), residential care (notably in the context of the on-going COVID-19 pandemic) (47%), (285) and transport (41%) sectors, which were far above the EU average (30%). The share of extremely strained jobs was nearly double the average (4%) in residential care and health sectors (Chart 2.29). By contrast, computer programming, consultancy and related services (9%) and architectural and engineering activities (14%) reported levels of job strain well below the EU average. (286) (287) Across shortage occupations, job strain was substantially higher for nurses (61%), carers (55%), drivers (44%), cooks and bartenders (43%), doctors (43%), and cleaners (36%). It was about average for building, sheet metal, electrical workers, and shop salespeople, and well below average for computer developers (Chart 2.30).

Chart 2.29

Job strain was highest for health, residential care, and transport workers

Job quality index (%), by subsector, EU-27

Source: Eurofound, EWCTS 2021.

Chart 2.30

Job strain for nurses was double the EU average

Job quality index (%), by shortage occupation, EU-27

Source: Eurofound, EWCTS 2021.

Nurses and carers indicated far higher than average exposure to all physical risks, physical demands, and social demands. A breakdown of the job quality index for shortage occupations experiencing above-average job strain reveals that work intensity is most severe for medical doctors and nurses, who report higher than average levels of working at high speed, to tight deadlines, and with elevated emotional demands. Looking at job prospects, between one-quarter and one-third of nurses, carers and cooks expect an undesirable change in their work situation. Nevertheless, workers in shortage occupations with above-average job strain (with the exception of cooks and bartenders) report a higher than average level of intrinsic satisfaction with their job, including feelings of carrying out useful work, being able to do their work well, and having enough opportunities to use their knowledge and skills in their current job.

Workers in occupations experiencing persistent labour shortages and significantly higher levels of job strain more often report that their health and safety is at risk because of their work (Chart 2.31). In 2021, the highest levels of health and safety at risk at work were reported by nurses (69%), drivers (53%), doctors (51%) and carers (50%), while it was on par with the EU average (34%) for cooks and bartenders. Data on non-fatal accidents at work also show elevated risks in the construction sector, with 48% of building workers and 47% of metal workers reporting health and safety risks at work. (288) Of the shortage occupations, only computer developers and sales workers report below average health and safety risks at work. Similar conclusions are drawn for shortage sectors experiencing higher levels of job strain, with over half (52%) of the workers in human health and land transportation, 47% of workers in residential care services, and 45% of workers in security activities reporting that their health and safety is at risk at work.

Chart 2.31

High shares of nurses, drivers, doctors and carers report health and safety risks at work

Proportion of workers reporting health and safety risks at work, shortage occupations, 2021, EU-27

Note: Occupations in red/orange/green have a job strain well above/close to/well below the EU average.

Source: Eurofound EWCTS 2021.

Most of the occupations characterised by persistent labour shortages involve substantial customer contact and activities in numerous work locations. Customer contact is less common for cleaners, developers, and metal workers. Except for three shortage occupations (doctors, nurses, computer developers), the use of digital technology at work is below average (see section 3.2.). With the exception of computer developers, activities of shortage occupations mostly take place outside workers’ homes, i.e. at their employers’ or clients’ premises, on the road, or from multiple locations.

When the gender segregation of occupations with persistent labour shortages is considered, three in four female-dominated occupations report higher than average job strain. These include nurses, carers, and cleaners. Gender-mixed shortage occupations, such as cooks and doctors, also report significantly poorer levels of job quality. Most male-dominated shortage occupations report average job strain, with substantially higher overall job quality for computer developers.

Overall, earnings, job strain and employment status could help to explain persistent labour shortages in certain subsectors. Analysing all factors across subsectors with persistent labour shortages, workers in social and residential care and workers in security and services to buildings activities have lower median gross hourly earnings, higher job strain and higher shares of temporary employment, compared to the EU average. (289) For the construction of buildings, non-standard employment forms are more common, with lower than average hourly earnings and job strain. By contrast, computer programming, architectural and engineering activities, and specialised construction services stand out as shortage subsectors with higher median gross hourly earnings, (290) lower job strain (291), and higher shares of solo self-employment than the EU average, with other factors (notably, skills) likely to determine their persistent shortages.

Job strain and adequate pay could play a role in explaining persistent shortages in certain occupations. Of the shortage occupations experiencing higher than average job strain, cleaners, cooks and bartenders, carers, salespeople, building workers, drivers and metal workers report above-average difficulties in making ends meet. Nurses indicate the highest job strain and health and safety risks at work and report less difficulty in making ends meet, but also feel they are not fairly rewarded. By contrast, computer developers and electronic workers report below-average job strain and less difficulty in making ends meet, pointing to other drivers (e.g. skills) as the primary cause of their persistent shortages.

Notes

- 258. More generally, employment and working conditions also depend on the productivity of sectors. They also support and accommodate the inclusion of wider groups of people in the labour market and can prevent premature labour market exit, for example due to illness.

- 259. Given that they are offered by employers, they are also characteristics of labour demand.

- 260. The analysis of variation here does not allow for an assessment of a causal relationship between working conditions and persistent labour shortages.

- 261. (European Commission, 2022g), (European Commission, 2023a).

- 262. (European Commission, 2018).

- 263. More information available here.

- 264. According to the ILO definition, working conditions cover a broad range of topics and issues, from working time (hours of work, rest periods, and work schedules) to remuneration, as well as the physical conditions and mental demands of the workplace.

- 265. Article 153 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) excludes pay from the scope of its actions in the area of working conditions.

- 266. More information available here.

- 267. Based on the latest available data of the Eurostat Structural Earnings Survey (SES).

- 268. Gross hourly earnings are defined as gross earnings in the reference month divided by the number of hours paid during the same period. The number of hours paid includes all normal and overtime hours worked and remunerated by the employer during the reference month.

- 269. Derived by dividing any economic aggregate of a country in national currency by its respective purchasing power parities.

- 270. At sectoral level, the persistent shortage sectors administrative and support services and transport and storage activities recorded the lowest median hourly earnings in PPS, with information and communication activities recording the highest (Chart A.4).

- 271. At sectoral level, the persistent shortage sectors administrative and support services and transport and storage activities recorded the highest share of low-wage earners, while information and communication activities recorded the lowest (Chart A.5).

- 272. Data based on the Eurofound 2021 European Working Conditions Telephone Survey (EWCTS).

- 273. Non-standard forms of employment analysed here include temporary employment and solo self-employment.

- 274. Own-account workers are those who, working on their own account or with one or more partners, hold the type of job defined as a self-employed job, and have not engaged any employees to work for them on a continuous basis during the reference period.

- 275. (Filomena and Picchio, 2021).

- 276. While temporary contracts can facilitate entry to the labour market for low-skilled and young workers, there is a risk they may not move to more stable and permanent jobs (European Commission, 2022g)

- 277. Solo self-employed people in the selected Member States are particularly vulnerable to in-work poverty (Horemans and Marx, 2017). A recent report also analyses the AROP and SMSD rates for solo self-employed workers in selected Member States (De Becker et al., 2022).

- 278. (Spasova and Wilkens, 2018).

- 279. For example, labour market segmentation is a major challenge in Poland. One instrument that impedes social security coverage is bogus self-employment. Civil law contracts are the most common instrument replacing full-time employment, with data suggesting that 20-30% of workers have these precarious contracts.

- 280. (European Commission, 2023a)

- 281. Residential care includes activities for the elderly and people with disabilities, those with mental and substance abuse issues, nursing, and other residential care activities.

- 282. At sectoral level, the share of temporary employment was above the EU average for administrative and support services, and human health and social work activities. The share of solo self-employment was above the EU average for professional, scientific, and technical activities, construction and information and communication activities (Chart A.6 and Chart A.7).

- 283. Based on the 2017 EU-LFS ad hoc module on self-employment, which defined dependent self-employment as having one client or one dominant client in the past 12 months.

- 284. No reliable data for the subgroup of own-account workers by sector.

- 285. Results should be interpreted within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, with the EWCTS being carried out between March and November 2021.

- 286. When the number of observations collected within a subsector/occupation of interest was too low to provide reliable statistical estimations, the respective subsector/occupation was merged with other subsector(s)/occupation(s) within the same sectoral/occupational group of close level.

- 287. Even though the EU average is referred to as a value distinguishing better and worse results, it is worth noting that not in all cases is the EU average itself is not always a satisfactory result.

- 288. In 2020, the highest incidence of non-fatal accidents at work in the EU was in construction, with 2 987 accidents per 100 000 people employed [HSW_N2_01].

- 289. Similarly, workers in health have much higher than average job strain and slightly higher shares of temporary employment, paired with above-average hourly earnings. Workers in transport and transport via pipelines activities report lower than average earnings and higher job strain, paired with lower shares of non-standard forms of work.

- 290. Aggregated due to sample sizes. In the case of civil engineering, median gross hourly earnings in PPS are reportedly in line with the EU average.

- 291. To note for the measurement of job strain the sub-sectors civil engineering and specialised construction services were merged, due to sample sizes.