6. Migrant employment in occupations with labour shortages

In the light of the ageing EU population and increasing labour shortages, improved participation of migrants in the labour market would strengthen their potential contribution to sustaining economic performance (see section 4.). Previous sections have discussed additional reskilling and upskilling needs, in particular related to the green and digital transitions, and the potential of increasing participation of other underrepresented groups to mitigate labour shortages, and this section considers the possible contribution of migrants in that context. More specifically, it analyses their occupational distribution and the main obstacles that could explain their lower labour market participation rates. Here, migrants are defined as people born outside the EU but residing in the EU, while people born in the country of residence are termed the native population. (239)

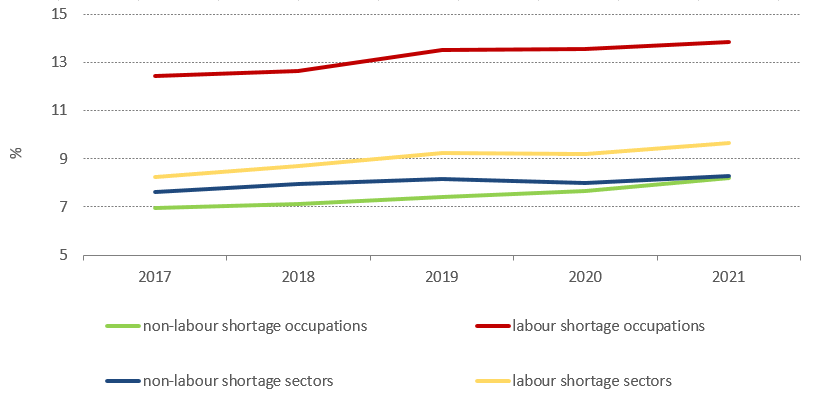

Chart 2.21

Higher share of migrants in labour shortage occupations and sectors

Share of migrants within labour shortage and non-labour shortage occupations and sectors, 2017-2021, EU

Note: Migrant and native workers identified based on country of birth. Analysis limited to population aged 20-64. Excludes data on Bulgaria, Hungary, Malta, Poland and Slovenia, as the EU-LFS files do not provide country of birth for people born outside Europe.

Source: EU-LFS 2017-2021.

In 2021, the share of migrants was higher in occupations characterised by persistent labour shortages in the EU. That share stood at 13.8%, compared to 8.2% in non-labour shortage occupations (Chart 2.21). There was strong heterogeneity in migrant share across labour shortage occupations, ranging from <10% for nursing and midwifery professionals, electrical equipment installers and repairers, machinery mechanics and repairers, and shop salespersons, to over 20% for cooks and domestic, hotel and office cleaners. Between 2017 and 2021, (240) the share of migrants increased almost equally in both labour shortage and non-labour shortage occupations, by 1.4 pp and 1.3 pp, respectively. In labour shortage occupations, the strongest increase in migrant share was observed for software and applications developers and analysts (+3.9 pp), followed by building finishers and related trade workers (+3 pp) and personal care workers in health services (+2.9 pp).

In 2021, sectors facing persistent labour shortages had a higher share of migrants compared to non-labour shortage sectors in the EU. Those shares were 9.6% and 8.3%, respectively (Chart 2.21). This difference was less pronounced than the gap in migrant share between labour shortage and non-labour shortage occupations, at 1.3 pp and 5.6 pp, respectively. In labour shortage sectors, the highest shares of migrants were in services to buildings and landscape activities (22.4%), residential care activities (12.4%), specialised construction activities (10.7%), and computer programming, consultancy and related activities (10.6%), with shares below 7% in repair and installation of machinery and equipment, human health activities, architectural and engineering activities, manufacture of other transport equipment, and manufacture of furniture. Between 2017 and 2021, the share of migrants increased more strongly in labour shortage sectors (1.4 pp) than non-labour shortage sectors (0.7 pp). The highest increases were observed in services to buildings and landscape activities (2.9 pp), computer programming, consultancy and related activities (2.8 pp), and residential care activities (2.5 pp).

Among occupations characterised by persistent labour shortages, the majority of migrants were concentrated in lower-skilled occupations in 2021 (Chart 2.22). (241) At 88.9%, this was significantly higher than their corresponding share within non-labour shortage occupations, at 57.7%. Overall, migrants were distributed quite equally between lower-skilled labour shortage occupations, lower-skilled non-labour shortage occupations, and higher-skilled occupations (around one-third in each), while native workers were more concentrated in higher-skilled non-labour shortage occupations (41.9%) and lower-skilled non-labour shortage occupations (34.7%). Around 1 in 10 migrants indicated that their current job requires lower skills than the last job they held before migrating, particularly for higher-educated migrants (14.5%), pointing to possible overqualification. However, around half did not have any work experience before migrating and likely accepted jobs that were less popular among native workers, potentially easing their entry into the labour market.

Chart 2.22

Migrants are concentrated in lower-skilled occupations

Segregation of migrant and native workers across occupations, by skill level, 2021, EU

Note: Migrant and native workers identified based on country of birth. Analysis limited to population aged 20-64. Excludes Bulgaria, Hungary, Malta, Poland and Slovenia, whose EU-LFS data do not provide country of birth for people born outside Europe.

Source: EU-LFS 2021.

Strong growth in the share of migrants was observed in higher-skilled occupations facing persistent labour shortages in the EU between 2017 and 2021. That share increased by 2.4 pp, compared to average increases of 1.4 pp in other occupations. For labour shortage occupations, the gap between the share of migrants in occupations with lower and higher skill levels decreased from 4.5 pp in 2017 to 3.5 pp in 2021, but remained stable for non-labour shortage occupations.

EU countries reporting shortages in occupations identified as experiencing persistent labour shortages tend to have a lower share of migrants working in those occupations. (242) In those countries, the share of migrants was 13.5% in 2021-2022, compared to 14.3% in countries not reporting labour shortages in shortage occupations. (243) (244) However, there were significant differences across labour shortage occupations. (245) For example, the share of migrants among building frame workers, and waiters and bartenders was more than 7 pp higher in countries with no labour shortages. For other occupations, such as machinery mechanics and repairers, sheet and structural metal workers, drivers, and personal care workers, the opposite was true, with the share of migrants higher in countries facing labour shortages. (246) This points to a positive contribution of migrants in alleviating labour shortages in certain occupations.

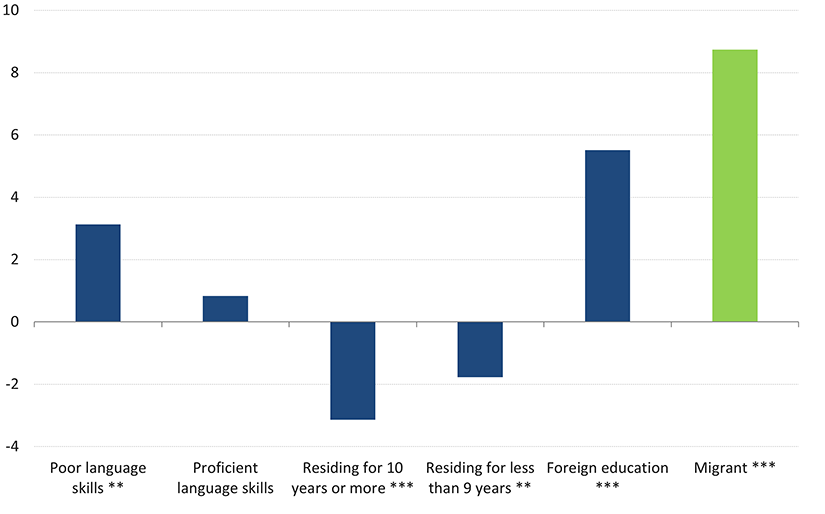

Chart 2.23

Migrants are more likely to be employed in occupations with persistent labour shortages

Factors connected to the probability of being employed in labour shortage occupations vs non-labour shortage occupations, 2021, EU

Note: Regression on full sample (migrants, natives, EU-mobile workers, identified based on country of birth). Analysis limited to population aged 20-64. Excludes Bulgaria, Hungary, Malta, Poland and Slovenia, whose EU-LFS data do not provide country of birth for people born outside Europe. Chart shows a selection of key variables of interest where the deviation from zero shows the difference with respect to the reference group in parenthesis: migrant (people born in the country of residence), foreign education indicates highest level of education achieved abroad (highest level of education achieved in country of residence), residing for less than nine years or residing for 10 years or more (born in the country of residence), proficient language skills comprising advanced and intermediate language skills or poor language skills comprising basic, hardly any, and no language skills (mother tongue). *** significant at 1%, ** significant at 5%, * significant at 10%, no * = not significant. For full set of results, see Figure A.1.

Source: EU-LFS 2021.

In addition to migrant status, completing the highest level of education abroad or possessing poor language skills (247) increase the likelihood of employment in occupations with persistent labour shortages. Here, being a migrant contributes +8.7 pp, while achieving the highest level of education abroad increases the likelihood by 5.5 pp, and low language skills by 3.1 pp (Chart 2.23). (248) The two latter factors may point to lower hiring requirements and indicate a lower skills demand in labour shortage occupations (see section 2.1.). The analysis shows that people residing in a country for a longer period are less likely to work in occupations characterised by persistent labour shortages than those who arrived more recently. This might indicate that integration prompts people to move to occupations that require higher skills and offer better pay or working conditions (see section 7.). Also, the higher concentration of migrants in lower-skilled occupations does not fully explain their higher probability of being employed in labour shortage occupations. After the skill level of the occupation is taken into account, the probability of migrants to be employed in labour shortage occupations decreases (to 5.5 pp), but remains significant and sizeable, confirming their role in mitigating labour shortages (Figure A.2).

Some untapped potential may remain in the current available pool of migrants. In 2021, the share of employed migrants (63.1%) was significantly lower than that of the native population (74.0%). This difference was more pronounced for women (53.9% of migrant women in employment, compared to 69.4% of native women). This may be linked to the fact that 58.7% of migrant women left their country for family reasons, compared to only 17.2% leaving for employment. Migrant women not in employment indicated care responsibilities as the most common reason for not searching for work. By contrast, family and employment were of about equal importance for men, each reported by around one-third of male migrants. (249) This suggests that a better care offer might increase the labour market participation of migrant women.

More than one-quarter of migrants reported facing obstacles to finding a suitable job in 2021. Host country language skills (24%), recognition of formal qualification obtained abroad (16%), and absence of suitable jobs (15%) were the most frequently cited obstacles. Indeed, 37.4% of migrants reported having little or no host country language skills before migrating, and also showed the highest share of participation in a language course (61.5%). More than one-fifth of migrants reported that their formal qualification obtained abroad was not recognised, they were unaware of the job possibilities or application procedures, or it was too costly, complex or not possible to apply. Only around one-third of migrants found their first job in the host country within the first three months, with slightly more than half finding work within the first year. Over one-tenth of migrants reported that it took longer than four years to find a job, or they did not manage to find a job at all, increasing the risk of long-term unemployment and depreciation of skills.

Chart 2.24

Migrants are less likely to be employed

Factors connected to the probability of being employed vs being not employed, 2021, EU

Note: Regression on full sample (migrants, natives, EU-mobile workers, identified based on country of birth). Analysis limited to population aged 20-64. Excludes Bulgaria, Hungary, Malta, Poland and Slovenia, whose EU-LFS data do not provide country of birth for people born outside Europe. Figure presents a selection of key variables of interest where the deviation from zero shows the difference with respect to the reference group in parenthesis: migrant (people born in the country of residence), foreign education indicates highest level of education achieved abroad (highest level of education achieved in country of residence), residing for less than nine years or residing for 10 years or more (born in the country of residence), proficient language skills comprising advanced and intermediate language skills or poor language skills comprising basic, hardly any, and no language skills (mother tongue). *** significant at 1%, ** significant at 5%, * significant at 10%, no * = not significant. For full set of results, see Figure A.3.

Source: EU-LFS 2021.

Having little or no skills in the main host country language reduces the likelihood of employment (Chart 2.24). That reduction is significant, at 8.9 pp. A recent study shows that the positive effect of better language skills is equally important across very different types of occupations, including low-skilled and medium-skilled jobs and occupations where immigrants are overrepresented. (250) Having achieved the highest level of education abroad decreases the probability of being employed by 1.8 pp, indicating some potential difficulties in recognising and fully utilising foreign qualifications. (251) The negative impact on the likelihood of employment decreases the longer a person resides in a country, but does not fully disappear, even after living there for 10 or more years. However, even when controlling for workers’ characteristics, (252) people born in a non-EU country have a lower probability of being employed than native workers (by 2.0 pp). A separate analysis limited only to migrants shows that migrating for employment reasons increases the probability of employment by 14.5 pp (Figure A.4). These results confirm the obstacles highlighted by migrants and imply unused potential among current migrants to mitigate labour shortages.

When in employment, migrants more often report experiencing discrimination. In 2021, the reported discrimination rate was 8.6% among migrants (5.4% for native workers), with most (65.2%) indicating their foreign origin as the most common reason. By contrast, native workers believed that the discrimination they perceived stemmed from gender (20.5%) or grounds other than age, disability or foreign origin (64.2%). Many studies show that higher-educated migrants are more likely than lower-educated migrants to report feeling discriminated against, with higher perceptions of discrimination associated with higher perceptions of being overqualified for their job. (253) Finally, anti-immigration attitudes have a negative and significant impact on migration inflows to the EU, which might hinder governments’ efforts to attract migrants with the required skills. (254)

Migrants more frequently work in non-standard forms of employment. (255) In 2021, one in five migrants was employed on a temporary contract, compared to around one in eight native workers. More migrants were employed on a contract with a temporary employment agency (4.7%, compared to 2.5% native workers). Migrants worked part-time more often (23.9%, compared to 18.2% native workers), a difference that was even more pronounced in labour shortage occupations, with around 10 pp more migrants in part-time jobs. This could indicate a missed opportunity in not increasing the working hours of migrants to mitigate labour shortages, particularly as 45.1% of migrants working part-time reported their willingness to work more hours (10.5 pp more than native workers).

Chart 2.25

Migrants are more likely to work in non-standard forms of employment

Factors connected to the probability of non-standard forms of employment vs full-time permanent employment, 2021, EU

Note: Regression on full sample (migrants, natives, EU-mobile workers, identified based on country of birth). Analysis limited to population aged 20-64. Excludes Bulgaria, Hungary, Malta, Poland and Slovenia, whose EU-LFS data do not provide country of birth for people born outside Europe. Chart presents a selection of key variables of interest where the deviation from zero shows the difference with respect to the reference group in parenthesis: migrant (people born in the country of residence), employed in labour shortage occupation (employed in non-labour shortage occupation), employed in lower-skilled occupation (employed in higher-skilled occupation), foreign education indicates highest level of education achieved abroad (highest level of education achieved in country of residence), residing for less than nine years or residing for 10 years or more (born in the country of residence), proficient language skills comprising advanced and intermediate language skills or poor language skills comprising basic, hardly any, and no languages skills (mother tongue). *** significant at 1%, ** significant at 5%, * significant at 10%, no * = not significant. For full set of results, see Figure A.5.

Source: EU-LFS 2021.

Migrants are more likely to have non-standard work arrangements (+3.1 pp) even when accounting for personal factors and employment in lower-skilled occupations or those characterised by persistent labour shortages (Chart 2.25). (256) This could be linked to social stigma or other characteristics not captured by the model, making it more difficult for migrants to find full-time permanent employment. This might increase their risk of detachment from the labour market and reduce their potential to contribute to alleviating labour shortages.

Further policies might be needed to strengthen the potential of migrants already residing in the EU to fill future labour shortages (see section 2.2.). Around 47.2% of migrants work in jobs that are likely to experience strong future shortages, compared to 37.6% of natives. (257) However, among those occupations, migrants are primarily concentrated in elementary occupations (38.6% of migrants, compared to 16.2% of native workers) and are strongly underrepresented in high-skilled non-manual occupations (23.4% of migrants, compared to 48.1% of native workers). Complementary to policies targeted at increasing participation rates of other population groups underrepresented in the labour market, such as women, policies addressing the inefficient use of skills of migrants already residing in the EU (due to difficulties in recognising their qualifications or overqualification related to discrimination) and insufficient investment in their upskilling and reskilling (including language skills) could help to reduce future labour shortages, especially in higher-skilled occupations.

Notes

- 239. EU-LFS does not include information on nationality and its change over time. This makes it impossible to use the definition for third-country nationals and EU citizens with migration background suggested in the European Commission Action Plan on Integration and Inclusion 2021-2027, which defines EU citizens with a migration background as nationals of EU Member States who had a third-country nationality and became EU citizens through naturalisation in one of the EU Member States, as well as EU citizens who have a third-country migrant background through their foreign-born parents (European Commission, 2020b). Given the data limitations, this section defines migrant and native workers based solely on their country of birth, without taking account of background. This leads to a much higher number of migrants than using the concept of nationality (around 25.6 million people born outside the EU, compared to 16.8 million third-country nationals in 2021). The analysis does not account for the possible persistence of intergenerational inequalities linked to migration for the native-born children of migrants (OECD, 2018). In addition, it only focuses on migrants residing in the EU and does not consider outsourcing to non-EU countries (which might have a significant impact for teleworkable jobs, such as call centres or ICT assistance), or offshoring to non-EU countries (which might be particularly relevant for manufacturing). This section does not cover intra-EU mobile workers, as their occupational mobility is extensively analysed in the European Commission Annual Report on Intra-EU Labour Mobility 2022 (European Commission, 2023a). That report showed a limited impact for intra-EU mobile workers in mitigating labour shortages in the short-term.

- 240. Comparison to earlier years is not possible – there is a break in time series for migrants as Germany’s EU-LFS data do not report country of birth for people born outside the country of residence before 2017.

- 241. Skill levels ‘1, 2 and 4’ and ‘2’ were grouped as lower-skilled; skill levels ‘3’, ‘3 and 4’ and ‘4’ were grouped as higher-skilled. All labour shortage occupations had a corresponding skill level of either ‘2’ or ‘4’.

- 242. Reported shortages by country taken from the 2022 EURES report on labour shortages and surpluses, primarily referring to the period between Q3 2021 and Q2 2022, depending on the country (ELA, 2023).

- 243. Part of this result could be driven by other country-specific factors, such as overall tightness of the labour market. For example, following the same methodology and based on (ELA, 2023), the migrant share in occupations facing persistent labour shortages was 4.4 pp higher in EU countries that did not report labour shortages in those occupations in 2020-2021 (compared to 0.8 pp in 2021-2022). This suggests that in recent years, persistent labour shortages in some occupations have (re-)emerged in some countries not previously facing labour shortages in occupations characterised by persistent labour shortages.

- 244. This result is in line with the 2022 EURES report on labour shortages and surpluses (ELA, 2023), which shows that in 2021, the share of people born outside the EU-27 and working in most widespread shortage occupations (11%) was higher than the share of those people in all occupations (8%).

- 245. Most of the countries reported severe labour shortages in the labour shortage sectors (at NACE 2-digit level) in 2021 (based on BCS and definition of severe labour shortages described in section 2.1.).

- 246. This may be related to the differences in regulation of those professions across countries (see Regulated Professions Database here).

- 247. Following the methodology in the EU-LFS 2021 ad hoc module on the labour market situation of migrants and their immediate descendants, analysis on language skills here focuses on the main host country language. For multilingual countries, the main host country language is the official language of the region where the respondent lives.

- 248. When controlling for degree of urbanisation, level of education, gender, length of residence in a country, age, temporary work, part-time work, size of the firm, country where highest level of education was achieved, and current language skills in the main host country language.

- 249. Studies show that migrating for family-related reasons is associated with poorer labour market outcomes than moving for employment or other reasons ( (Gillespie, Mulder and Thomas, 2021), (Kanas and Steinmetz, 2021), (Lens, Marx and Vujic, 2018)).

- 250. (Carlsson, Eriksson and Rooth, 2023).

- 251. Overall, receiving some part of their education abroad (i.e. through Erasmus or other exchange programmes) might be linked to higher employability and earnings’ potential ( (Kratz and Netz, 2018), (Wiers-Jenssen, Tillman and Matherly, 2020)). However, this analysis considers the country where the highest level of education was successfully completed rather than international Employment and Social Developments in Europe 2023 education experience more generally. While the findings suggest that completing the highest level of education abroad is likely to lower the probability of being employed, the results might be more diverse when considering the impact on earnings, which is outside the scope of this analysis (Wiers-Jenssen and Try, 2005).

- 252. Characteristics considered: degree of urbanisation, level of education, gender, length of residence in the country, age, country where the highest level of education was achieved, and current language skills in the main host country language.

- 253. (OECD, 2018), (Schaeffer, 2019), (Steinmann, 2019), (Migration Policy Group, 2022).

- 254. (Di Iasio and Wahba, 2023) show that a 10% increase in negative attitudes reduces migration inflows by 0.4%. However, this effect is smaller than for other economic factors, such as income and unemployment.

- 255. Defined as having a temporary job, or a contract with a temporary employment agency, or working part-time.

- 256. Controlling for degree of urbanisation, level of education, gender, length of residence in a country, age, temporary work, part-time work, size of the firm, country where highest level of education was achieved, current language skills in the main host country language, and employment in labour shortage or lower-skilled occupations.

- 257. Occupations with a future shortage indicator with a value of at least 2.7 (Table 2.4).