EU Assistance to Myanmar/Burma

About the report We examined EU development support to Myanmar/Burma and concluded that it had been partially effective. The EU played a leading role in supporting development priorities and allocated significant funding to the country. However, we report on shortcomings in the Commission’s assessment of needs and in the implementation of EU assistance.

On the basis of the observations in this report, the Court formulates a number of recommendations designed to improve the management of the development aid.

Executive summary

IMyanmar/Burma was experiencing major and difficult political and economic transition during the period audited. Factors such as natural disasters, ethnic conflicts and the limited capacity of local actors and authorities were hampering development efforts.

IIWe examined whether EU support to Myanmar/Burma had been effective. To this end, the audit addressed whether the European External Action Service (EEAS) and the Commission supported well established development priorities. It also assessed the Commission’s management of EU development aid and asked whether EU development support had achieved its objectives. The audit focused on expenditure committed to from 2012 to 2016 under the Development Cooperation Instrument (DCI), following the establishment of a civilian government in 2011. In total, the EU has allocated almost one billion euro for the 2012-2020 period.

IIIWe concluded that EU development support to the country had been partially effective. The EU played an important leading role in supporting development priorities, and allocated significant funding to the country. In a difficult context, where the institutional set-up, progress with the peace process and pace of reforms were uncertain, the EU responded actively to the country’s needs. However, we report on shortcomings in the Commission’s assessment of needs and in the implementation of EU assistance.

IVThe Commission’s decision to focus on four sectors was not in line with the 2011 Agenda for Change, and the EU Delegation’s capacity to cope with the heavy workload was not assessed. The Commission did not sufficiently assess the geographical priorities within the country. Domestic revenue mobilisation did not figure in the consideration of priorities, even though it is a key factor for Myanmar’s development. Joint programming by the EU and individual Member States under the 2014-2016 Joint Programming Strategy was a positive step.

VManagement of EU development aid was generally satisfactory. The actions addressed the country’s development priorities but there were delays. The Commission’s choice of aid modality was reasonable. However, the justification for the amount of funding allocated to each sector and action was not documented. Implementation was also delayed because the 2016 Annual Action Programme (AAP) had never been adopted.

VIImplementation of the UN-managed Trust Fund programmes was affected by delays and slow budget absorption for programme activities. These Funds have accumulated large cash balances but the Commission has not ensured that interest earned on the EU contribution is retained for the actions being funded. Cost-control provisions in the EU-UN contracts had little impact.

VIIOver the 2012-2016 period the Commission used the crisis declaration provisions widely to contract directly with implementing partners. The removal of the requirement for calls for proposals reduced the transparency of the selection procedure and risked having an adverse effect on the cost-effectiveness of projects.

VIIIThe degree to which results were achieved under the projects audited varied. Only half of the projects audited delivered the planned outputs, mainly because of implementation delays. The outcomes and sustainability of the results could not be assessed for almost half of the projects audited because of the delayed implementation of programme activities. Weaknesses were also noted with regard to the quality of project indicators and project monitoring.

IXOn the basis of the observations in this report, the Court formulates a number of recommendations designed to improve the management of the development aid to Myanmar/Burma. The EEAS/Commission are asked to:

- better focus the areas of support in order to increase the impact of the aid;

- strengthen coordination with DG ECHO;

- justify and document the allocation of funding to sectors and for actions;

- enhance the cost-effectiveness of multi donor actions;

- improve project management and ensure that EU actions have more visibility.

Introduction

01Following several decades of authoritarian rule, Myanmar/Burma has been undergoing political and economic transition under a civilian government that took office in March 2011. The government has launched a series of reforms designed to change the country’s political, democratic and socio-economic situation.

02As regards the country’s economic situation, its GDP grew at an average annual rate of 7.5 %1. The workforce is young and the country is rich in natural resources, such as gas, timber, gold and gemstones. Bordering the markets of the two most populous countries in the world, China and India, the country is enjoying a significant increase in direct investment.

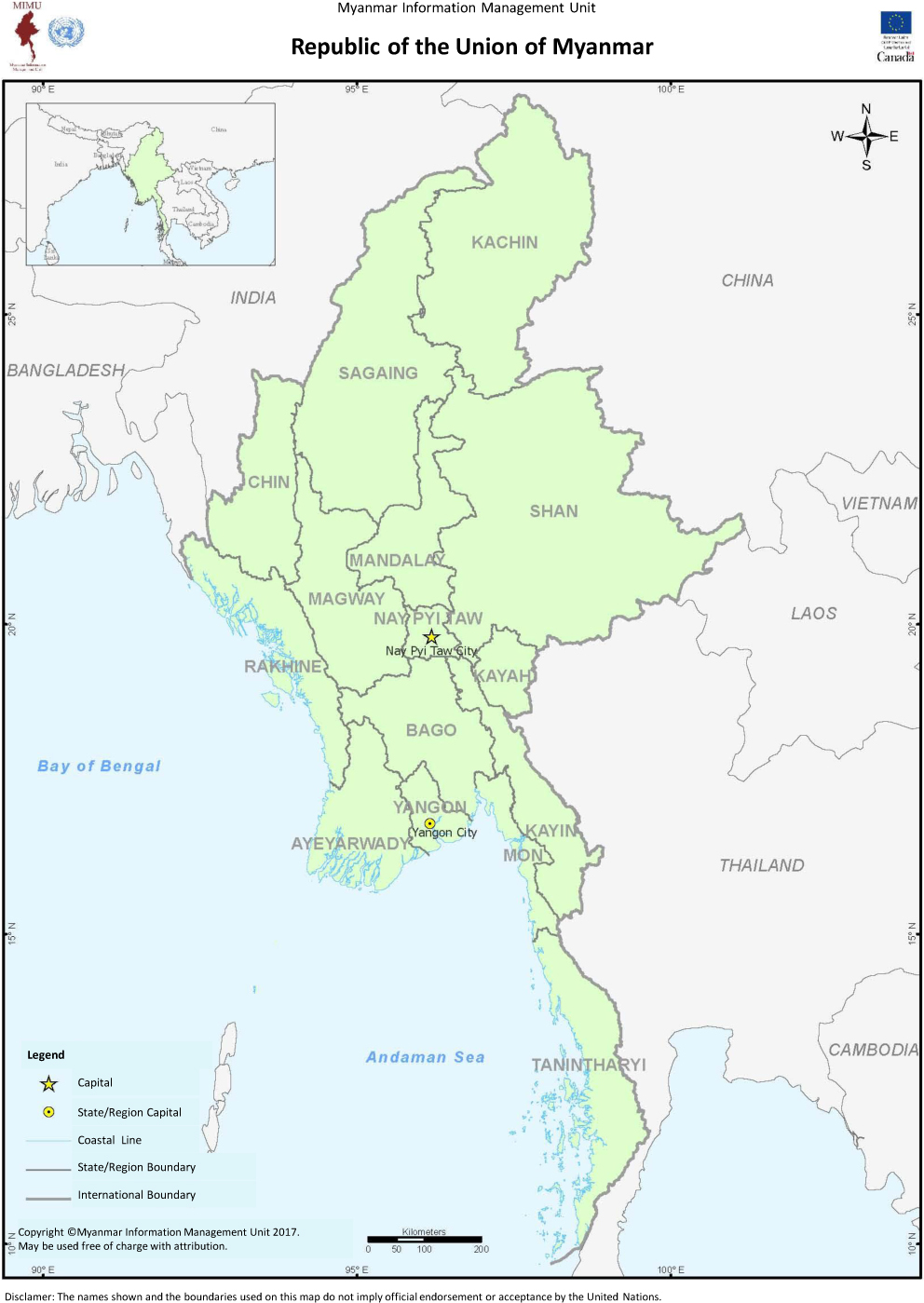

03The population comprises numerous ethnic groups, some of which are embroiled in long-running civil wars. Inter-ethnic and inter-religious tensions persist. The government has signed a Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement with some ethnic armies but the peace process is progressing slowly. Ethnic tensions prevail in states with non-Bamar ethnic groups, particularly in the border regions of the Shan, Kachin and Rakhine States (see map in Annex I).

04In 2016 and 2017 there were renewed outbreaks of violence against the Muslim Rohingya minority in the state of Rakhine (see map in Annex I), a people effectively rendered stateless when the 1982 Burmese Citizenship Law came into force. Recurrent violence exacerbates the conflict and hinders humanitarian and development efforts in the region.

05In order to encourage the reform process, in April 2012 the EU suspended the sanctions imposed on the government and by 2013 had lifted all but the arms embargo. The EU also opened an office in Yangon, which became a fully-fledged EU Delegation in 2013.

06The Council Conclusions of 22 July 2013 on the Comprehensive Framework for the EU's policy and support to Myanmar/Burma frame the bilateral relations. The strategic objectives of this Framework are to (1) support peace and national reconciliation, (2) assist in building a functioning democracy, (3) foster development and trade, and (4) support the re-integration of Myanmar into the international community.

07An EU-Myanmar/Burma Task Force meeting was held in November 2013 to present to the government the tools and instruments the EU has at its disposal to support democratisation. Chaired by former EU High Representative Catherine Ashton and one of the country’s Ministers of the President's Office U Soe Thane, a series of forums were held to deepen the bilateral relationship in a number of areas, including development assistance, civil society, the peace process, and trade and investment.

08The Task Force meeting was followed by EU-Myanmar Human Rights Dialogues, which explored how EU assistance could support efforts to foster human rights, democratic governance and the rule of law on the ground. The EU offered to support the Myanmar government in ratifying international human rights conventions and instruments. The EU also deployed an Election Observation Mission to observe the general election on 8 November 2015.

09The EU has allocated more than one billion euro for the 2007-2020 period (see Table 1), mainly under bilateral, regional and thematic instruments2.

| (million euro) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | 2007-2011 | 2012-2013 | Special Package 2012-2013 | Total 2007-2013 | 2014-2020 | Total 2007-2020 |

| Development Cooperation Instrument | ||||||

| Bilateral envelope | 32.0 | 93.0 | 125.0 | 688.0 | 813.0 | |

| Thematic programmes | 43.9 | 7.7 | 34.0 | 85.6 | 20.6* | 106.2 |

| Regional programmes | 17.0 | 3.8 | 20.0 | 40.8 | 35.9* | 76.7 |

| Other Instruments (IfS, EIDHR, ICI+) | 2.2 | 28.9 | 3.7 | 34.8 | 1.8 | 36.6 |

| Total | 95.1 | 40.4 | 150.7 | 286.2 | 746.3 | 1,032.5 |

* Funding allocation up to 2017.

Source: 2007-2013 and 2014-2020 Multiannual Indicative Programmes (MIPs) and 2007-2015 Annual Action Programmes (AAPs).

10Under the 2007-2013 Multiannual Indicative Programme (MIP) the EU provided bilateral funding for two focal sectors, i.e. education and health. Thematic instruments and regional funding focused mainly on the Food Security and Aid to Uprooted People programmes.

11In 2012, in order to keep up the momentum of the reforms, the EU provided further support to the country under a “Special Package” amounting to 150 million euro. Given this funding, bilateral support was broadened to cover two more focal sectors, i.e. peacebuilding and trade.

12Under the 2014-2020 MIP, bilateral funding totalling 688 million euro has been allocated to four focal sectors: rural development, education, governance and peacebuilding. Together with assistance to the country under thematic and regional programmes and instruments, EU funding for the country over the seven-year period comes to 746.3 million euro. The funding allocated to each sector for the period 2007-2020 is set out in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Allocation of bilateral, regional and thematic funding to each sector under DCI (in million euro)

Sources: 2007-2013 MIP, 2014-2020 MIP, 2007-2015 AAPs.

The funds were implemented using both the direct and indirect management modes.3 In 2016 the EU channelled 63 %4 of funding to the country under indirect management, mostly through UN-agencies. The following Trust Funds were involved: the Livelihoods and Food Security Trust Fund (LIFT), the Quality Basic Education Programme (QBEP), the Three Millennium Development Goals Fund (3MDG) and the Joint Peace Fund (JPF). The percentage of the EU’s contributions to the Funds ranged between 11 % and 37 % (see details in Annex II). Direct management expenditure, consisting primarily of grants, accounted for 37 % of the overall portfolio.

14The country has received support from many donors. Over the 2012-2016 period donor commitments from all sources totalled over 8 billion USD. In addition to the aid from the EU, the country received commitments from Japan (3.3 billion USD), the World Bank (1 billion USD), the UK (593 million USD) and the US (477 million USD)5.

Audit scope and approach

15The audit examined whether EU support to Myanmar/Burma was effective by addressing the following three questions:

- Did the European External Action Service (EEAS) and the Commission support well established development priorities?

- Did the Commission manage EU development aid well?

- Did the EU’s development support achieve its objectives?

The audit covered expenditure committed to over the 2012-2016 period and financed under the DCI. We examined 20 projects - 11 projects under the indirect management mode (of which 10 were managed by Trust Funds6 and one was implemented by a Member State Agency7), and nine projects under direct management8. The details of the projects audited are provided in Annex III.

17The audit work involved a desk review of documentary evidence, such as programming documents and monitoring and evaluation reports. It included a mission on the spot and interviews with staff from the Directorate-General for International Cooperation and Development (DG DEVCO), the EEAS, the EU Delegation and the Directorate-General for European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations (DG ECHO), as well as representatives of EU Member States to Myanmar/Burma, other donors, and implementing partners. Other bodies’ audit, verification9 and Results-Oriented Monitoring (ROM) reports were also taken into account.

Observations

Despite certain weaknesses, the EU played a leading role in supporting established development priorities

18In order to answer the first audit question (see paragraph 15), we assessed whether the EEAS and the Commission had addressed the country’s needs. We also assessed whether the Commission’s development priorities were sufficiently focused and whether it had coordinated them with other donors.

The EEAS and the Commission addressed the country’s needs

19The EEAS and the Commission responded rapidly to the political changes in the country. They initiated human rights dialogue, deployed an Election Observation Mission and engaged in the peace process. The EU Delegation to Myanmar/Burma was set up in 2013. Despite the new structure of the EU Delegation and the local challenges encountered, the EEAS and the Commission established an early and active policy dialogue with the national authorities and ensured that extensive knowledge-gathering was carried out.

20The government of Myanmar/Burma has not agreed a national plan for the country’s development. The needs of the country were extensive and covered many areas, including peace, education, health, agricultural development, governance and institutional capacity. The choice of sectors to be supported was determined in consultation with stakeholders, and the government considered that this tied in with its general development priorities. The EU has allocated significant funding to the country to support development priorities (see paragraph 9).

The choice of development priorities was not sufficiently focused

21Within the framework of the MIPs for Myanmar/Burma, the EEAS and the Commission specified the development priorities and funding allocations. Programming had to be in line with global EU development-policy priorities and implement the 2011 Agenda for Change10. It also had to ensure coherence and complementarity between the various donors and alignment with government priorities.

22The primary objective of the 2011 Agenda for Change was to significantly increase the impact and effectiveness of EU development policy. It called for EU involvement in a maximum of three focal sectors, so as to increase the impact and leverage of its assistance. The Commission decision to increase the number of focal sectors from two to four (see paragraphs 10 to 12) was not clearly justified in accordance with the Commission’s own operating guidelines, and did not take account of the EU Delegation’s capacity to cope with such a large development portfolio in a complex working environment.

23Furthermore, the Commission did not sufficiently assess geographical priorities in terms of regions. For example, the first study on Rakhine state’s specific needs (see paragraph 4) was not carried out until 2017. Such prioritisation could have increased the impact of EU support.

24The generation of government revenue from tax or non-tax sources is a crucial factor in sustainable development, particularly in a country rich in natural resources (see paragraph 2). However, domestic revenue mobilisation was not given due consideration in determining the priorities, even though it is key to Myanmar’s development.

The level of coordination varied

25Once the civilian government came to power in Myanmar/Burma there was a rapid influx of donors with funds for development (see paragraph 14). The country’s government and the development partners had regular meetings and exchanges of information to ensure donor coordination. Their meetings served to improve development aid coherence and effectiveness. The EU took an active part in the cooperation fora.

26The EU and its Member States set up the 2014-2016 Joint Programming Strategy to promote aid effectiveness. Joint Programming was achieved in spite of the absence of a national development plan and was one of the first such examples worldwide. Even though aid-effectiveness gains were modest in terms of reducing aid fragmentation, the joint programming process brought about improved transparency, predictability and visibility.

27However, coordination between DG ECHO and DG DEVCO was inadequate. Humanitarian aid is much needed in certain regions of Myanmar/Burma, particularly in the states of Rakhine and Kachin. Between 2012 and 2016 the European Commission, through DG ECHO, provided some 95 million euro to relief programmes for food security and to assist victims of conflict. Even though both Commission DGs were active in the country, EU humanitarian interventions were not taken into account sufficiently when programmes were formulated. There was also no joint implementation plan linking relief, rehabilitation and development (LRRD). There were examples of cooperation in the spheres of humanitarian and development aid, but they constituted the exception rather than the rule.

28Moreover, DG ECHO was not included in the 2014-2016 Joint Programming Strategy defined by the Commission and the Member States (paragraph 26). This was a missed opportunity to improve coordination, given that humanitarian assistance is expected in areas of protracted crisis, which is the case with some of the country’s regions. A procedure for exchange of information between DG DEVCO and DG ECHO was not formalised until September 2016.

The Commission’s management of EU development aid was generally satisfactory but was affected by delays and shortcomings

29In order to answer the second audit question (see paragraph 15) we assessed whether the Commission had identified and implemented the actions well and selected the appropriate aid modality. We also assessed whether the Commission had coordinated the actions with other donors, and the actions had been monitored properly.

Actions were relevant but there were setbacks

30Under each MIP the Commission adopts financing decisions, i.e. Annual Action Programmes (AAPs), that define the actions, aid modality and total amount of funding for each action. The actions selected were in line with the priorities determined. However, although the focal sectors and the actions supported were in line with government priorities (see paragraph 20), the Commission did not document the determination of the amount of funding, both for each sector under the MIP and for each action under the AAPs.

31The 2016 AAP was not adopted, as some Member States were not supportive of the approach proposed prior to a meeting of the Development Cooperation Instrument (DCI) Committee. The Commission decided to withdraw the proposal. The non-adoption of the 2016 AAP caused considerable delays in implementing the planned actions, as the implementation of 163 million euro under the MIP for 2016 was postponed. Of the total allocation of almost one billion euro for the 2012-2020 period (see Table 1), the amounts committed up to April 2017 accounted for 380.7 million euro.

32The operational criteria considered when the aid modalities were selected and the Implementation Plan was developed were the “future workload of the Delegation” and assuring “a mix of aid modalities”. None of the AAPs reviewed included the criterion of cost-effectiveness of the activities funded. Nevertheless, given the options at hand, the Commission’s choice of aid modalities was reasonable.

33More than half of the amounts committed were allocated under the indirect management mode, and channelled mostly through UN-managed Trust Funds (see paragraph 13). This allowed the Commission to work in close cooperation with other donors and be involved in large-scale development actions. This aid modality alleviated the burden on Commission staff, as the UN was primarily responsible for managing the Funds.

Implementation by the Trust Funds was affected by delays in committing and disbursing funds

34The Commission committed and disbursed funds to the Trust Funds quickly, but implementation of the UN-managed Trust Fund programmes was affected by delays and slow budget absorption for programme activities. The amounts disbursed for programme activities from LIFT accounted for just 53 % of the contributions to the Fund (with duration 2012-2018), and in the case of 3MDG just 68 % (with duration 2012-2017). Even though the JPF was set up in December 2015, only 3 % of the funding contributed had been paid out in programme activities11.

35Due to the slow implementation of programme activities the cash balances of the UN-managed Trust Funds were sizeable. In the case of LIFT, 3MDG and the JPF, they amounted to 74 million USD, 54 million USD and 18 million USD12, respectively13.

36The contractual provisions signed between the EU and UNOPS, the UN agency that manages three of the four Trust Funds in Myanmar/Burma, allow the latter to retain the interest earned on funds advanced by the Commission. The Commission does not require UNOPS to allocate the interest earned to programme activities.

Cost-control provisions in EU-UN contracts had little impact

37The contractual provisions governing EU funding paid into UN Multi Donor Trust Funds are set out in contribution agreements. These outline the financial commitments of both parties. A specific clause in these contribution agreements states that indirect costs should be limited to 7 % of direct eligible costs incurred by the Funds. As the UN manages the Funds, cost-control is primarily its responsibility. However, the Commission also has an obligation to ensure cost-effectiveness as regards EU contributions. One of the ways it tries to ensure this is by means of verification checks it carries out on the Funds.

38During these checks the verifiers examine the eligibility of the costs submitted by the Trust Funds. In accordance with the agreement reached between the parties, if expenditure is found to be ineligible for EU funding, it will not be disallowed but will be borne by other donors, when sufficient funds are available. This is the so-called “notional approach”. We encountered instances where verifications on behalf of the Commission had detected ineligible costs and the notional approach was applied (see Box 1).

Box 1

Examples of the application of the notional approach

LIFT

In 2012 a verification check by the Commission detected ineligible costs of 7.35 million euro, comprised mainly of advances and loans, incorrectly reported as expenditure. By applying the notional approach the total ineligible expenditure was reduced to 2.44 million euro, as the Trust Fund management reported that sufficient funds were available from other donors to cover 4.91 million euro of the costs determined by the Commission to be ineligible. Subsequently, most of the remaining 2.44 million euro was offset by the Commission against further payments to LIFT, and eventually a balance of 0.35 million euro was recovered from UNOPS.

3MDG / 3DF

In 2012 the Three Diseases Fund (3DF) ceased its activities and 3MDG took over. A verification exercise carried out in 2015 on the Three Diseases Fund (3DF) reported ineligible indirect costs of 640 000 USD. The specified ceiling for indirect costs of 7 % of direct eligible costs specified in the contribution agreement had been exceeded by this amount. When the Fund management was notified of this it informed the Commission that the sum had been covered by funds from other donors.

The examples above illustrate the limited extent to which the Commission can exercise control over the cost-effectiveness of the Funds. In most cases costs which are found to be ineligible by the Commission will be met by other donors. Thus, the findings of the verification checks will have little or no impact on the cost-effectiveness of the Funds. This is also the situation for indirect costs, in the absence of agreement among the donors on the application of an appropriate percentage rate.

40In cases where a donor is also an implementing partner in a multi-donor action, such as in the QBEP (see Annex II and Box 2), there is a significant risk that indirect costs exceeding the 7 % agreed with the EU will be allocated to the implementing partner itself or to other donors.

Box 2

Example of high indirect costs

In the case of the QBEP, indirect costs were twice as high as provided in EU-UN contracts: in addition to the 7 % indirect costs included in the QBEP general budget, a further 7 % was included in the sub-grant budget for projects implemented via International Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs). The costs paid under these sub-grants are allocated to non-EU funding sources. Nevertheless, the overall cost-effectiveness of an action is diminished by the double charging of indirect costs, irrespective of the funding source to which the costs are assigned.

Crisis contract procedures were applied too broadly

41The Commission decided on all directly managed projects, including their scope and budget, and was able to monitor progress closely throughout the lifespan of a project. Tools such as the ROM exercise were used to assist the Commission in its management. The Commission was also in a position to take action during the course of a project. However, both the setting-up of projects and their monitoring are demanding, time-consuming activities, especially when they are numerous and spread across wide areas that are difficult to access. The Commission therefore aimed to fund large projects.

42Over the 2012-2016 period the Commission used the crisis-declaration14 provisions to contract directly with implementing partners without any need for calls for proposals. Use of the crisis declaration meant that there was “imminent or immediate danger threatening to escalate into armed conflict”, and grants and procurement contracts could be negotiated without engaging in a call for proposals or tenders15. Initially, the crisis declaration applied solely to the ethnic states of Chin, Kachin, Kayah, Kayin, Mon, Shan and Rakhine and in the Tanintharyi Division (see map in Annex I). In 2014 the Commission extended the crisis declaration to all contracts “supporting peace and state-building goals in Myanmar” and renewed it each year. The crisis declaration was understandable for the areas directly affected by conflict but less so for peaceful areas. The removal of the requirement for calls for proposals reduced the transparency of the selection procedure and risked having an adverse effect on the cost-effectiveness of projects.

43Although the Commission has itself invoked the crisis declaration since 2012, it only informed the implementing partners of the possibility of applying flexible procedures in 2015 and 2016, and not in 2013 and 2014. While the Commission awarded grants directly, it required the implementing partners to apply contractual procurement procedures in 2013 and 2014, even in the ethnic states.

The risk of double funding was not sufficiently mitigated

44When assessing the Commission’s management of development assistance we found that the risk of double funding was in some cases significant but not mitigated (see Box 3).

Box 3

Examples of risks of double funding

The 3MDG Fund covers three components: (1) Maternal, New-born and Child Health; (2) Tuberculosis, Malaria and HIV/AIDS; (3) Systems Support. Component 2 is also covered by the Global Fund, which is based in Geneva, Switzerland, operates worldwide, including in Myanmar/Burma, is co-funded by the EU, and managed by UNOPS. The 3MDG funding for Component 2 is specifically intended to complement that provided by the Global Fund in Myanmar/Burma, and to fill any gaps. However, there was no comprehensive assessment of the gaps and overlaps between the two Funds16. No details concerning both Funds’ areas of intervention and their budgets have been presented to either the 3MDG Fund Board or the Commission. Mitigation measures to address the risk of double funding were not taken.

In another case one local NGO received EU support for capacity building from four different EU-funded sources in the absence of any assessment of possible funding overlaps.

In addition, two of the projects audited revealed weak coordination with other donors at the implementation level (see Box 4).

Box 4

Examples of missed opportunities in terms of coordination

In 2012 the World Bank committed more than 80 million USD to a “National Community Driven Development (CDD) Program”. This programme was implemented through various government development structures, including township authorities.

In one region, the EU funded a project for five million euro that included a CDD component. A monitoring report noted that the initiatives had been implemented through the same stakeholders at township level. This created parallel structures and serious overlaps, albeit that the communities benefited from additional investment in their infrastructure.

In another region, the EU funded a project for seven million euro that also included a CDD component. The monitoring report pointed to a lack of sector coordination and the risk of overlaps in this case as well.

There were weaknesses in the monitoring of EU-funded actions and visibility was low

46The Commission’s actions were monitored, reported and evaluated via project reporting, field visits, ROM reports, evaluations and audits. Monitoring improved in the years after the EU Delegation had been set up, but there were still weaknesses.

47It was impossible to assess whether the outputs and outcomes set at the level of an AAP had been attained, for two reasons: some of the AAPs examined did not have output or outcome indicators to allow the actions to be assessed; even where indicators were available, there were no aggregated data on the outputs and outcomes of the various actions carried out in each intervention sector under the AAPs.

48Some of the AAPs call for a performance-monitoring committee to be set up for the actions funded. In the cases audited this committee had either not been set up or had been set up late. In addition, we noted weaknesses in monitoring in 50 % of the projects audited (see Annex IV), half of which comprised Trust Fund projects.

The Commission reacted slowly to verification mission reports

49The Commission is a member of the boards of the LIFT, 3MDG and JPF Funds and of the QBEP’s steering committee. It also carries out verification missions at UN-agencies. The Commission initiated and reacted to verification mission reports slowly (see Box 5).

Box 5

Verification missions

LIFT

The Commission carried out a verification mission in 2012 which detected ineligible costs amounting to 7.35 million euro. The final outstanding amount was not recovered until five years later, in January 2017.

3MDG/3DF

Despite the fact that the 3DF Fund was phased out in 2012, no verification mission was carried out until 2015, with the results being published in 2016, i.e. four years later. No verification mission has been carried out in respect of 3MDG.

EU visibility was low

50Verification mission reports and monitoring reports signalled the low level of visibility of EU-funded actions. The level could be assessed in 10 of the projects audited, and in eight cases did not fully comply with the contractual provisions (see Annex IV).

51Among the advantages of EU Trust Funds is increased visibility. As an initiator of the Joint Peace Fund, the Commission played a major role in designing and setting it up. It had initially considered the option of an EU Trust Fund, but subsequently formally excluded it from the Fund design study because it had been unable to convince the other potential contributors of the merits of this option.

The achievement of objectives was affected by implementation delays

52In order to answer the third audit question (see paragraph 15) we assessed whether the actions delivered the planned outputs and achieved the expected outcomes. The details of the projects audited are provided in Annex III and an overview of the assessment of the individual projects is presented in Annex IV.

Some good results, despite the difficult context

53The objectives of projects funded by the EU were to respond rapidly and flexibly across a range of areas relevant to Myanmar's political transition, and to support the development of policy on economic and social issues. Both external and internal factors had a negative impact on the delivery of results, and undermined the effectiveness of the projects funded. Despite the difficult context, some of the projects we audited achieved good results (see Box 6).

Box 6

Examples of projects that achieved good results

LIFT – Microfinance project

The purpose of the project was to increase the access to loans and other financial services of over 100 000 low-income clients in the country, at least half of whom are either women or reside in rural areas. LIFT provided microfinance institutions with support that allowed them to operate and continue providing services. The project was successful as many availed of the financing to start up or expand their activities.

3MDG – Project supporting Maternal and Child Health

The country’s health sector suffers from inadequate public expenditure, and the maternal and child mortality rates are very high. The project funded by 3MDG supported emergency referral for both pregnant women and children under five years of age. Patients received payments to cover transport, food and treatment costs. The project is likely to significantly contribute to reducing maternal and child mortality.

Project 20

This project involved the construction and improvement of educational facilities in various locations in Rakhine State for IDP and non-IDP children from the Rakhine and Rohingya communities. At the time of the Court’s visit, although it was early to assess the expected outcomes, the project was delivering the outputs as planned.

Delays and weaknesses affected project implementation

54While some of the planned outputs of the projects audited were delivered on time, many were not. In total, 75 % of the projects audited suffered from delays in implementation (see Annex IV).

55In the case of both UN Trust Fund projects and projects under direct management, most were relevant to the objectives defined. However, there were shortcomings in this regard in a quarter of the projects audited (see Box 7).

Box 7

Example of a project only partially relevant to the objectives defined

The objective of an important project for capacity building at institutional level was to strengthen public institutions and non-state actors. However, the project’s scope and deliverables were overly broad and not fully in line with the focal sectors, as they also related to areas such as “the environment” and the “Erasmus” programme.

The objectives of most of the projects audited met the SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, timely) criteria, but the indicators for half the projects we audited were inadequate. In general, no baseline or target values had been set for these projects, which hampered the Commission’s monitoring of the rate of implementation, as well as assessment of the extent to which objectives had been achieved.

57Most of the projects audited achieved some or all of the planned outputs. However, we could not assess the outcomes and sustainability of the results for nearly half of the projects audited because of the delayed implementation of programme activities. Only in one-third of the projects audited was it likely that the expected outcomes would be achieved.

58The Commission’s ROM reports generally evaluated the effectiveness of the directly-managed projects in the sectors assessed as “good”, but the average sustainability assessment was “problematic”.

The support to Rakhine state did not achieve significant results

59Of a total financial commitment to the country of 380.7 million euro (see paragraph 31), 38.8 million euro has been allocated to Rakhine state. The financial allocation targeting Rakhine state is based on the lessons learnt by a small number of implementing partners. The results expected of most of the projects in our sample that were implemented in Rakhine state were only partially achieved (see Box 8).

Box 8

Food Security project in Rakhine state

LIFT supported a food security project in Rakhine state. Poor results have been achieved since it began in 2013, owing to both

- external challenges, such as violent attacks on international NGOs, and

- internal deficiencies, such as low field-implementation capacity and weak cooperation between implementing partners.

Despite the LIFT management being aware of the situation, after the project expired LIFT contracted the same partners to continue implementing the project and no call for proposals had been launched.

The objective of the newly established JPF is to support a nationally-owned and inclusive peace process in Myanmar/Burma (see Annex II). However, the Fund’s largest component does not target Rakhine. This represents a missed opportunity as far as this highly vulnerable region is concerned.

Conclusions and recommendations

61Over the 2012-2016 period Myanmar/Burma was undergoing political and economic transition. Factors such as natural disasters, ethnic conflicts and the limited capacity of local actors and authorities were hampering development efforts.

62The audit examined whether EU support to Myanmar/Burma was effective. We concluded that EU development support to Myanmar/Burma had been partially effective. In a difficult context the EU played an important and leading role in supporting development priorities and allocated significant funding to the country. However, we report on shortcomings in the Commission’s assessment of needs and in the implementation of EU assistance.

63The Commission’s decision to focus on four sectors was not in line with the 2011 Agenda for Change and the Commission’s own operating guidelines, and did not take into account the EU Delegation’s capacity to cope with the heavy workload. There was no assessment of geographical priorities within the country. Generation of domestic revenue was not considered in determining the development priorities (see paragraphs 22 to 24).

Recommendation 1 – The need to focus support to increase impact

The Commission and the EEAS should:

- focus on not more than three specific areas of intervention, or justify further sectors;

- foster domestic revenue mobilisation;

- rank priorities in accordance with the most urgent regional needs and the level of support provided by other donors on a geographical basis for the country.

Timeframe: by the next programming period starting 2020.

64Joint programming by the EU and individual Member States under the 2014-2016 Joint Programming Strategy was a positive step (see paragraph 26). Coordination between the DGs managing the development and humanitarian assistance in areas of protracted crisis did not work well. The Commission did not draw up a joint implementation plan for LRRD (see paragraph 27).

Recommendation 2 – Coordination of the interventions

The Commission should:

- develop an implementation plan with DG ECHO that links relief, rehabilitation and development particularly in areas of protracted crisis;

- include humanitarian aid in the new programming document drawn up with EU Member States (Joint Programming Strategy).

Timeframe: end of 2018.

65The management of EU development aid was generally satisfactory. The actions addressed the country’s development priorities but there were delays. The Commission’s choice of aid modality was reasonable. However, the justification for determining the amount of funding to be allocated to each sector and action was not documented. Implementation was also delayed, as the 2016 AAP was never adopted (see paragraphs 30 to 33).

Recommendation 3 – Implementation of the actions

The Commission should:

- justify and document the allocation of funding to each focal sector and each action.

Timeframe: programming phase of the new MIP (2019/2020).

66Implementation of the UN-managed Trust Fund programmes was affected by delays and slow budget absorption for programme activities (paragraph 34). The UN-managed Trust Funds have accumulated significant cash balances but the Commission has not ensured that interest earned on the EU contribution is retained for the actions being funded (see paragraph 36). The cost-control provisions in EU-UN contracts had limited impact (see paragraphs 37 to 40). The Commission reacted slowly to verification mission reports (see paragraph 49).

Recommendation 4 – Cost-effectiveness of the multi-donor actions

The Commission should:

- endeavour to agree an appropriate level of indirect costs with other donors.

Timeframe: end of 2018.

67During the 2012-2016 period the Commission used the crisis-declaration provisions to contract directly with implementing partners. The widespread removal of the requirement for calls for proposals reduced the transparency of the selection procedure and risked having an adverse effect on the cost-effectiveness of projects (see paragraphs 41 to 43).

68Monitoring improved over the years, but there were some weaknesses. There were insufficient output and outcome indicators for assessing the actions. The Commission did not ensure that the performance-monitoring committees were set up in accordance with Commission Decisions (see paragraph 48). Generally, the EU’s support was not sufficiently visible (see paragraph 50).

Recommendation 5 – Monitoring of the actions

The Commission should:

- consolidate the available information so that outputs and outcomes set at the level of AAPs may be better assessed;

Timeframe: 2019.

- insist that the provisions concerning the visibility of EU actions are applied.

Timeframe: end of 2018.

69The degree to which results were achieved under the projects audited varied significantly. Only half the projects audited delivered the planned outputs, mainly because of implementation delays (see paragraph 54). The projects in the Court’s sample that were implemented in Rakhine state did not achieve significant results (see paragraph 59). The fact that the newly established Joint Peace Fund does not target the highly vulnerable region of Rakhine state represents a missed opportunity (see paragraph 60).

Recommendation 6 – Achievement of results

The Commission should:

- improve project management to avoid delays in project implementation;

- explore again the possibility of Rakhine state being placed in the Joint Peace Fund’s sphere of competence.

Timeframe: end of 2018.

This Report was adopted by Chamber III, headed by Mr Karel PINXTEN, Member of the Court of Auditors, in Luxembourg at its meeting of 12 December 2017.

For the Court of Auditors

Klaus-Heiner LEHNE

President

Annexes

Annex I

Map of Myanmar/Burma

Annex II

UN-managed Trust Funds

The Livelihoods and Food Security Trust Fund (LIFT) is a multi-donor trust fund with the objectives of helping the poor and disadvantaged people of Myanmar/Burma out of poverty, and assisting them in overcoming malnutrition and building livelihoods. The Fund is managed by the United Nations Office for Project Services (UNOPS).

The Three Millennium Development Goals Fund (3MDG) has the objectives of reducing the burden of three communicable diseases (HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria) and improving the health of mothers and children in Myanmar/Burma. The Fund took over the Three Diseases Fund (3DF) in 2012, when the latter’s activities ceased. It is managed by UNOPS.

The Quality Basic Education Programme (QBEP) was set up with the objective of increasing equitable access to basic education and early childhood development, especially in disadvantaged and hard-to-reach communities. It is managed by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF).

The Joint Peace Fund (JPF) is intended to support a nationally-owned and inclusive peace process in Myanmar/Burma. It was established in 2015 and is managed by UNOPS.

| (million USD) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sector of intervention | Fund | Period | Donor Funds contributions | EU contribution committed | % of EU commitments to total donor contributions | As at |

| Food security/ Livelihood/ Rural Development |

LIFT | 2009-2017 | 439.7 | 130.2 | 30% | 31.1.2017 |

| Health | 3MDG | 2012-2017 | 279.6 | 31.5 | 11% | 1.11.2016 |

| Education | QBEP | 2012-2017 | 76.6 | 28.5 | 37% | 31.12.2016 |

| Peacebuilding | JPF | 2015-2017 | 105.2 | 20.8 | 20% | 28.2.2017 |

Source: ECA.

Annex III

Sample of projects audited

| (million) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contract No | Sector of intervention | Contractor | Contracted | Paid | Starting date | End date of operations |

| Livelihoods and Food Security Trust Fund (LIFT) | UNOPS | 81.8 EUR | 47.5 EUR | 1.1.2012 | 31.12.2018 | |

| 1 | Agri-business project | Private Company | 18.1 USD | 11 USD | 18.12.2015 | 31.12.2018 |

| 2 | Food Security project | NGO | 22.1 USD | 15 USD | 1.3.2013 | 31.12.2015 |

| 3 | Food Security project | NGO | 10.5 USD | 4.3 USD | 1.1.2016 | 31.12.2018 |

| 4 | Microfinance project | UN Agency | 7.0 USD | 6.7 USD | 1.11.2012 | 31.12.2018 |

| 5 | Market Access project | NGO | 4.0 USD | 3.4 USD | 11.6.2014 | 10.6.2017 |

| 6 | Food Security project | NGO | 2.1 USD | 0.8 USD | 10.6.2016 | 31.5.2019 |

| Three Millennium Development Goals Fund (3MDG) | UNOPS | 27.5 EUR | 22.4 EUR | 1.1.2013 | 31.12.2017 | |

| 7 | Tuberculosis project | UNOPS | 13.0 USD | 4.5 USD | 1.10.2014 | 31.12.2017 |

| 8 | Maternal and Child Health | NGO | 6.8 USD | 5.6 USD | 1.7.2014 | 31.12.2017 |

| Quality Basic Education Programme (QBEP) | UNICEF | 22.0 EUR | 21.7 EUR | 1.1.2013 | 30.6.2017 | |

| 9 | Early Childhood Care | Clerical Association | 4.0 USD | 3.1 USD | 23.10.2014 | 30.6.2016 |

| 10 | Early Education Response | NGO | 2.4 USD | 1.3 USD | 15.10.2013 | 20.6.2017 |

| (million euro) | ||||||

| 11 | Governance | Member State Agency | 20.0 | 9.4 | 1.8.2015 | 31.7.2019 |

| 12 | Governance | Private company | 12.2 | 2.4 | 1.10.2015 | 30.9.2018 |

| 13 | Aid to Uprooted People | NGO | 8.0 | 5.5 | 10.7.2012 | 9.4.2017 |

| 14 | Peacebuilding | UN Agency | 7.0 | 3.8 | 15.3.2015 | 14.3.2019 |

| 15 | Peacebuilding | NGO | 7.0 | 4.4 | 1.2.2015 | 31.7.2018 |

| 16 | Aid to Uprooted People | NGO | 5.6 | 5.0 | 29.12.2012 | 14.8.2017 |

| 17 | Peacebuilding | NGO | 5.0 | 2.8 | 1.3.2015 | 31.8.2018 |

| 18 | Peacebuilding | NGO | 5.0 | 1.0 | 1.10.2016 | 30.9.2020 |

| 19 | Aid to Uprooted People | NGO | 3.2 | 2.9 | 1.2.2013 | 30.4.2017 |

| 20 | Peacebuilding | Clerical Association | 2.0 | 1.6 | 1.1.2015 | 31.12.2017 |

Annex IV

Assessment of the individual projects - overview

| No | Well selected | Relevant | LOGFRAME | Well monitored | On schedule/ budget absorption |

Outputs delivered | Likely to achieve the expected outcomes | Sustainability of the action/exit strategy | EU visibility | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMART objectives | RACER indicators | Baseline/ target values |

|||||||||

| 1 | Partially | Yes | Partially | Partially | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Too early | Too early | Partially |

| 2 | Yes | Yes | Partially | Partially | Partially | No | No | No | No | Partially | No |

| 3 | Partially | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Partially | Partially | Partially | Too early | Too early | Partially |

| 4 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Partially | Partially | No |

| 5 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | Partially | No |

| 6 | Yes | Yes | No | Partially | Partially | Partially | Partially | Partially | Too early | Too early | Partially |

| 7 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Partially | No | Partially | Too early | Too early | Not assessed |

| 8 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Partially | Yes | Yes | Partially | Not assessed |

| 9 | Partially | Partially | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not assessed |

| 10 | Partially | Partially | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Too early | No |

| 11 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Partially | Partially | Too early | Too early | Not assessed |

| 12 | Yes | Partially | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Partially | Too early | Too early | Not assessed |

| 13 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Partially | No | Partially | No | Partially | Partially | No | Not assessed |

| 14 | Partially | Partially | Yes | Partially | Partially | Yes | Partially | Partially | No | Partially | Not assessed |

| 15 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Partially | Partially | Yes | Too early | Too early | Yes |

| 16 | Partially | Yes | Yes | Partially | No | Yes | No | Partially | Partially | Yes | Not assessed |

| 17 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Partially | Partially | Partially | Partially | Yes | Yes | Yes | Partially |

| 18 | Partially | Yes | Yes | Partially | N/A | Too early | No | Too early | Too early | Too early | Too early |

| 19 | Partially | Partially | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Partially | Yes | Partially | Partially | Not assessed |

| 20 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Partially | Yes | Partially | Yes | Too early | Too early | Yes |

Acronyms and abbreviations

AAP: Annual Action Programme

CDD: Community-Driven Development

DCI: Development Cooperation Instrument

DG DEVCO: Directorate-General for International Cooperation and Development

DG ECHO: Directorate-General for European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid

EIDHR: European Instrument for Democracy and Human Rights

EEAS: European External Action Service

ICI+: Instrument for Cooperation with Industrialised Countries

IcSP: Instrument contributing to Stability and Peace (formerly the Instrument for Stability (IfS))

IDP: Internally Displaced Person

JPF: Joint Peace Fund

LIFT: Livelihoods and Food Security Trust Fund

LRRD: Linking Relief, Rehabilitation and Development

MIP: Multiannual Indicative Programme

NGO: Non-Governmental Organisation

QBEP: Quality Basic Education Programme

RACER: Relevant, Accepted, Credible, Easy and Robust

ROM: Results-Oriented Monitoring

SMART: Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, Timely

SWITCH-Asia: EU-funded programme to help consumers and businesses switch to sustainable consumption and production

UNICEF: United Nations Children’s Fund

UNOPS: United Nations Office for Project Services

3DF: Three Diseases Fund

3MDG: Three Millennium Development Goals Fund

Endnotes

1 World Bank data, 2012-2016.

2 Funding instruments can be country-based (bilateral), regional or have a specific thematic focus.

3 Under direct management the European Commission is in charge of all EU budget implementation tasks, which are performed directly by its departments either at its headquarters or in the EU Delegations. Under indirect management the Commission entrusts budget implementation tasks to international organisations, the development agencies of EU Member States, partner countries or other bodies.

4 Out of 438 million euro for all contracts (Source: 2016 External Assistance Management Report).

5 Ministry of Planning and Finance, Foreign Economic Relations Department, https://mohinga.info/en/dashboard/location/.

6 Projects 1 to 10.

7 Project 11.

8 Projects 12 to 20.

9 Commission’s audit performed on UN-agencies.

10 The primary objective of the Agenda for Change, adopted in 2011, is to significantly increase the impact and effectiveness of EU development policy. See https://ec.europa.eu/europeaid/policies/european-development-policy/agenda-change_en.

11 As at 31 January 2017 for LIFT, 1 November 2016 for 3MDG and 28 February 2017 for the JPF. Dates vary due to different reporting cycles.

12 See above.

13 UNICEF could not provide certified cash flow statements for the QBEP.

14 Article 190(2) of Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) No 1268/2012 of 29 October 2012 on the rules of application of Regulation (EU, Euratom) No 966/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council on the financial rules applicable to the general budget of the Union (OJ L 362, 31.12.2012, p. 1).

15 As defined in Article 128 of the Financial Regulation No 966/2012, Article 190(2) of Commission Delegated Regulation No 1268/2012 of 29 October 2012 on grants, Article 190 of the Financial Regulation No 966/2012, Article 266(1)(a) of Commission Regulation No 1268/2012 on services, Article 190 of the Financial Regulation No 966/2012, Article 268(1)(a) of Commission Regulation No 1268/2012 on supplies, Article 190 of the Financial Regulation No 966/2012, Article 270(1)(a) of Commission Regulation No 1268/2012 on works.

16 For the biggest project under this component the initial analysis in 2013 indicated that this action would require a budget of USD 0.7 million, noting that the Global Fund was already supporting it to approximately USD 12.7 million. Nevertheless, in 2014 the action was granted USD 11.4 million, a figure that rose to USD 13 million in 2015, but there was no explanation as to why the needs had increased so significantly.

| Event | Date |

|---|---|

| Adoption of Audit Planning Memorandum (APM) / Start of audit | 22.11.2016 |

| Official sending of draft report to Commission | 11.10.2017 |

| Adoption of the final report after the adversarial procedure | 12.12.2017 |

| Official replies of the Commission and the EEAS received in all languages | 20.12.2017 |

Audit team

The ECA’s special reports set out the results of its performance and compliance audits of specific budgetary areas or management topics. The ECA selects and designs these audit tasks to be of maximum impact by considering the risks to performance or compliance, the level of income or spending involved, forthcoming developments and political and public interest.

This performance audit was carried out by ECA Chamber III, which is responsible for auditing spending on external actions, security and justice. The Reporting Member, Mr Karel Pinxten, Dean of the Chamber, was supported in the preparation of the report by Gerard Madden, his Head of Private Office, Mila Strahilova, Attaché and Head of Task, Beatrix Lesiewicz, Principal Manager, Roberto Ruiz Ruiz and Francesco Zoia Bolzonello, Auditors. Linguistic support was provided by Cathryn Lindsay.

Contact

EUROPEAN COURT OF AUDITORS

12, rue Alcide De Gasperi

1615 Luxembourg

LUXEMBOURG

Tel. +352 4398-1

Enquiries: eca.europa.eu/en/Pages/ContactForm.aspx

Website: eca.europa.eu

Twitter: @EUAuditors

More information on the European Union is available on the internet (http://europa.eu).

Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2018

| ISBN 978-92-872-8974-2 | ISSN 977-5679 | doi:10.2865/141504 | QJ-AB-17-025-EN-N | |

| HTML | ISBN 978-92-872-8991-9 | ISSN 1977-5679 | doi:10.2865/90946 | QJ-AB-17-025-EN-Q |

© European Union, 2018.

For any use or reproduction of photos or other material that is not under the European Union copyright, permission must be sought directly from the copyright holders.

GETTING IN TOUCH WITH THE EU

In person

All over the European Union there are hundreds of Europe Direct Information Centres. You can find the address of the centre nearest you at: https://europa.eu/european-union/contact_en

On the phone or by e-mail

Europe Direct is a service that answers your questions about the European Union. You can contact this service

- by freephone: 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (certain operators may charge for these calls),

- at the following standard number: +32 22999696 or

- by electronic mail via: https://europa.eu/european-union/contact_en

FINDING INFORMATION ABOUT THE EU

Online

Information about the European Union in all the official languages of the EU is available on the Europa website at: http://europa.eu

EU Publications

You can download or order free and priced EU publications from EU Bookshop at: https://op.europa.eu/en/web/general-publications/publications. Multiple copies of free publications may be obtained by contacting Europe Direct or your local information centre (see http://europa.eu/contact)

EU law and related documents

For access to legal information from the EU, including all EU law since 1951 in all the official language versions, go to EUR-Lex at: http://eur-lex.europa.eu

Open data from the EU

The EU Open Data Portal (http://data.europa.eu/euodp/en/data) provides access to datasets from the EU. Data can be downloaded and reused for free, both for commercial and non-commercial purposes.

Special Report

Special Report