3. Selected types of social investment

3.3. Investing in skills

Effective investment in skills can increase employment, competitiveness and productivity, fostering economic growth. (162) skills needs, particularly in the context of the green and digital transitions, will require additional investment in adult learning, upskilling and reskilling. These investments can improve employability prospects, addressing skills shortages and mismatches.(163) Investment in lifelong learning helps people to develop their skills in line with labour market needs throughout their entire career, increasing their chances of remaining in the labour market. A labour force with an up-to-date skillset is central to boosting productivity and growth, supporting wages as well as firms’ competitiveness. (164) The European Pillar of Social Rights Action Plan sets an EU headline target of at least 60% of adults participating in training each year by 2030, compared to a participation rate of 39.5% in 2022. The analysis below examines a selection of social investments and illustrates the return on investment in skills of young unemployed people and productivity-enhancing training for the broader population. Within this, Box 3.4 provides additional analysis on the investment needs related to re- and upskilling in the context of the green transition.

Investment in skills for young unemployed people

Young people who are not in employment nor in education or training (NEET) face a higher risk of becoming disconnected from the labour market and social exclusion, with potential negative long-term effects on their entire working lives. (165) In the context of the European Pillar of Social Rights Action Plan, the EU strives to reduce the share of young people who are NEET, from 12.6% in 2019 to 9% by 2030. Different types of interventions and pathways can support young people to enter the labour market. For instance, a majority of trainees feel that a past traineeship experience supported their professional development and made their transition from school to work easier. (166) Vocational education and training and apprenticeships can help develop job-related skills and help young people enter the labour market.

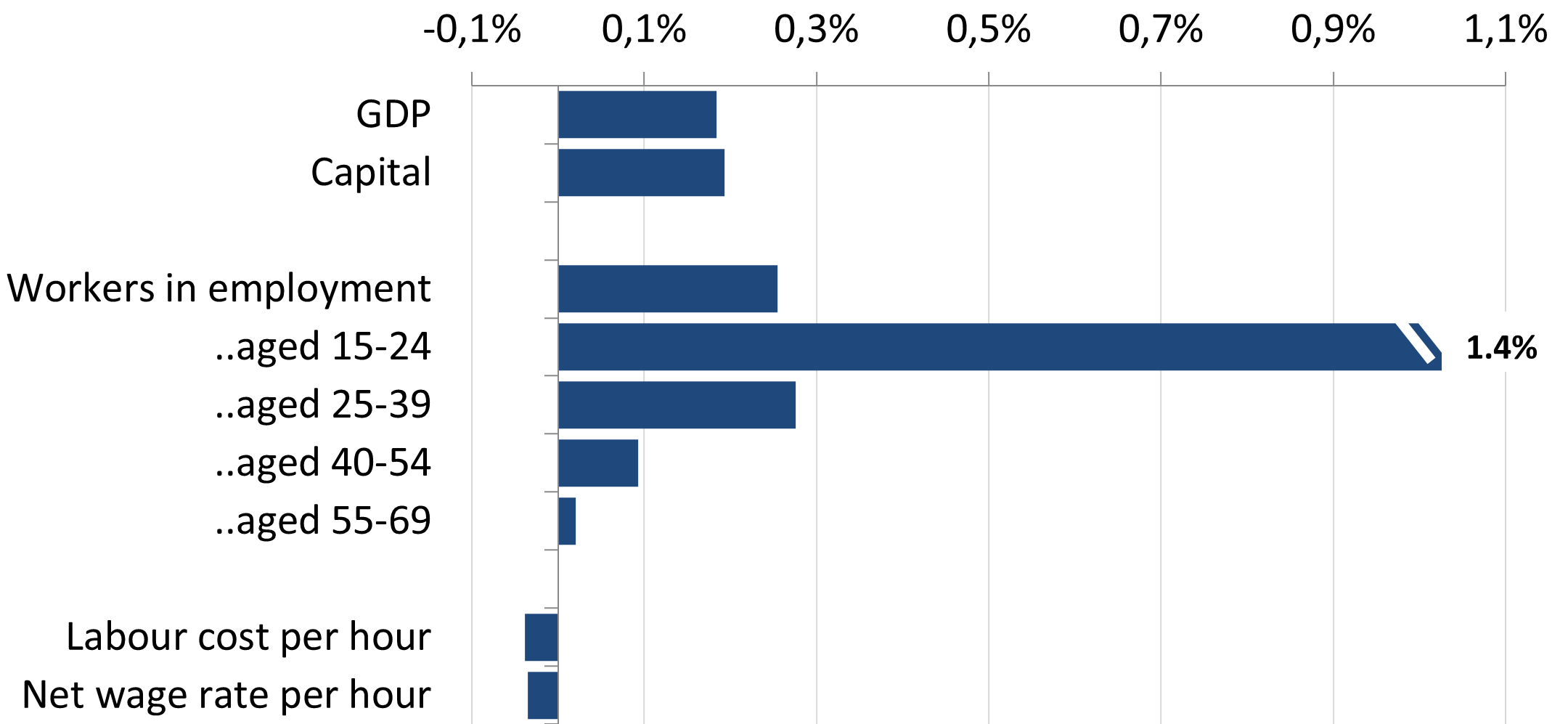

Additional well-designed investment to increase the skills of young unemployed workers is expected to increase employment across all ages in the long term. Investing in the skills of young unemployed people (aged 15-24) can tackle high youth unemployment rates. The average macroeconomic effects of skill-enhancing interventions for young unemployed people for the six countries with the highest youth unemployment rates in 2022 (167) were estimated using DG EMPL’s Labour Market Model (LMM) (Box A3.1 in the Annex). (168) Based on the model simulation, young workers are expected to experience the strongest employment gains, with the number of people aged 15-24 employed increasing by 1.4% due to around a 0.1 pp increase in investment in skill-enhancing training (Chart 3.7). Overall, employment is expected to increase by 0.25%, with early investment in skills assumed to have a sustainable, although decreasing, impact on employability throughout people’s lives. Increasing investment in skills for young unemployed people can contribute to upward social convergence. Assuming that training is well-designed – and thus effective at enhancing skills and reducing unemployment rates – the analysis suggests that the additional spending would lead to a small reduction in disparities and prompt catching-up in unemployment and employment rates, not only for the beneficiaries of the training (aged 15-24) but for the overall working-age population. (169)

Chart 3.7

Skills-enhancing investments for young unemployed people are expected to increase employment and GDP in the long-term

Long-term impact of investment in skills of young unemployed people (aged 15-24) compared to no-policy (reference) scenario

Source: DG EMPL calculations based on LMM.

Helping young people to improve their employability leads to broader positive macroeconomic returns, driving investment and GDP. The initial cost of the measure is estimated to be more than offset by larger economic returns. The overall rise in employment is expected to trigger additional investment to equip new workers with additional capital. As a result, GDP is projected to increase by 0.18% in the long term, compared to a scenario without any additional investment in young unemployed people (Chart 3.7).

Investments in skills enhance productivity

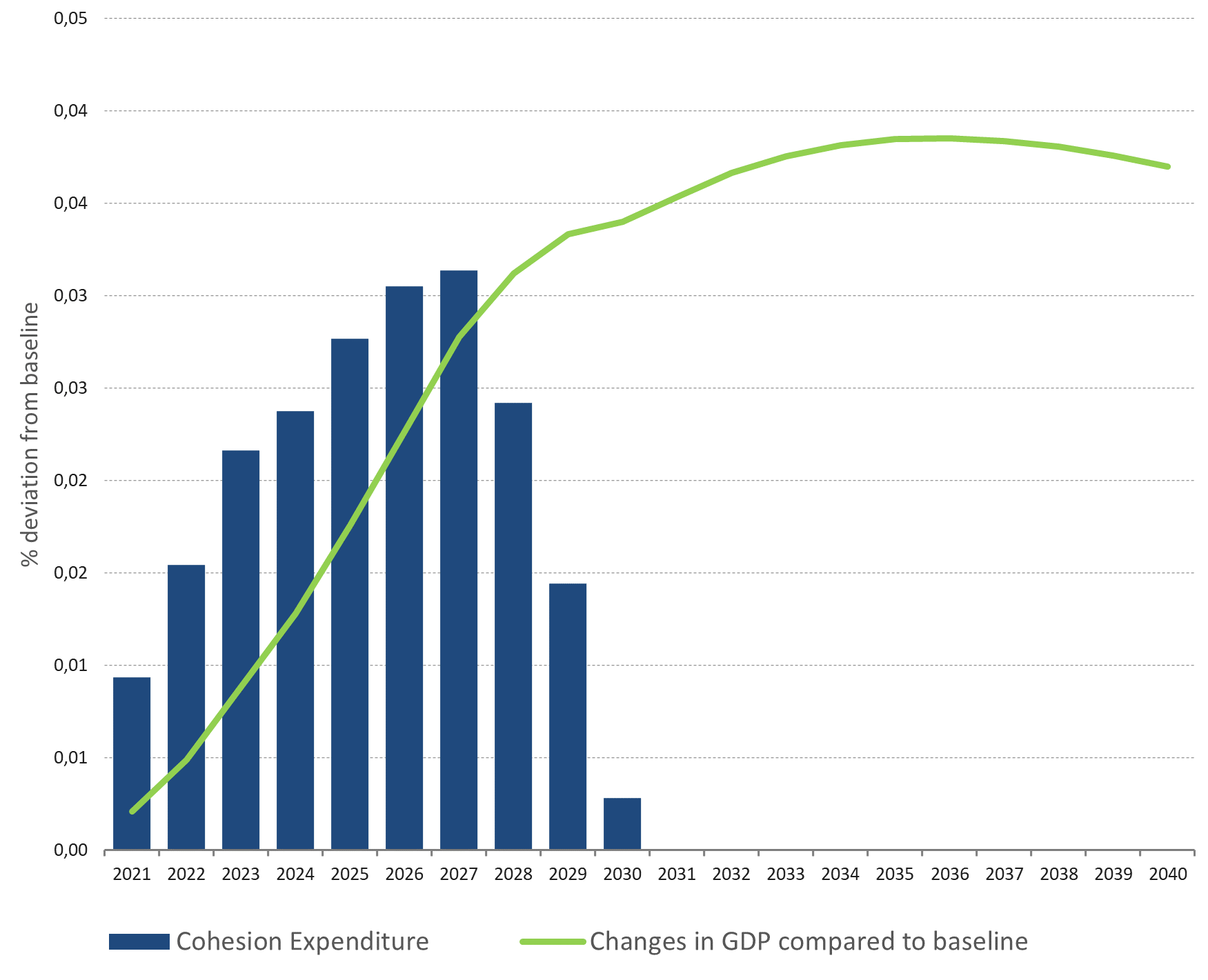

Regional investment in skills in the context of the European Social Fund Plus (ESF+) can lead to significant increases in economic activity in the long term.The European Commission’s RHOMOLO model is used to simulate the potential regional macroeconomic impact of ESF+ investments in skills over the 2021-2027 funding period, which are assumed to increase labour productivity (Box A3.1 in the Annex). (170) The simulations illustrate that ESF+ funding for skills, in addition to the direct employment and social benefits expected in the areas and sectors targeted by the projects financed, could increase EU GDP by up to 0.039% at its peak in 2036 relative to baseline GDP (Chart 3.8). GDP is expected to remain above its baseline level even after expenditure on ESF+ terminates, as the structural effects of increased labour productivity and corresponding adjustments by firms and households materialise. Overall, the initial cost of the measure, at less than 0.035% of GDP per year, is more than offset by the long-term economic returns, which are significantly larger than the original investment.

Chart 3.8

Investment in skills can lead to long-term GDP gains

Expenditure on skills-related ESF+ programmes over 2021-2027 programming period (% over baseline GDP) and expected impact of the investment on GDP (% deviation from baseline GDP)

Note: 'Baseline’ constitutes a scenario with no additional investment.

Source: JRC calculations based on RHOMOLO model.

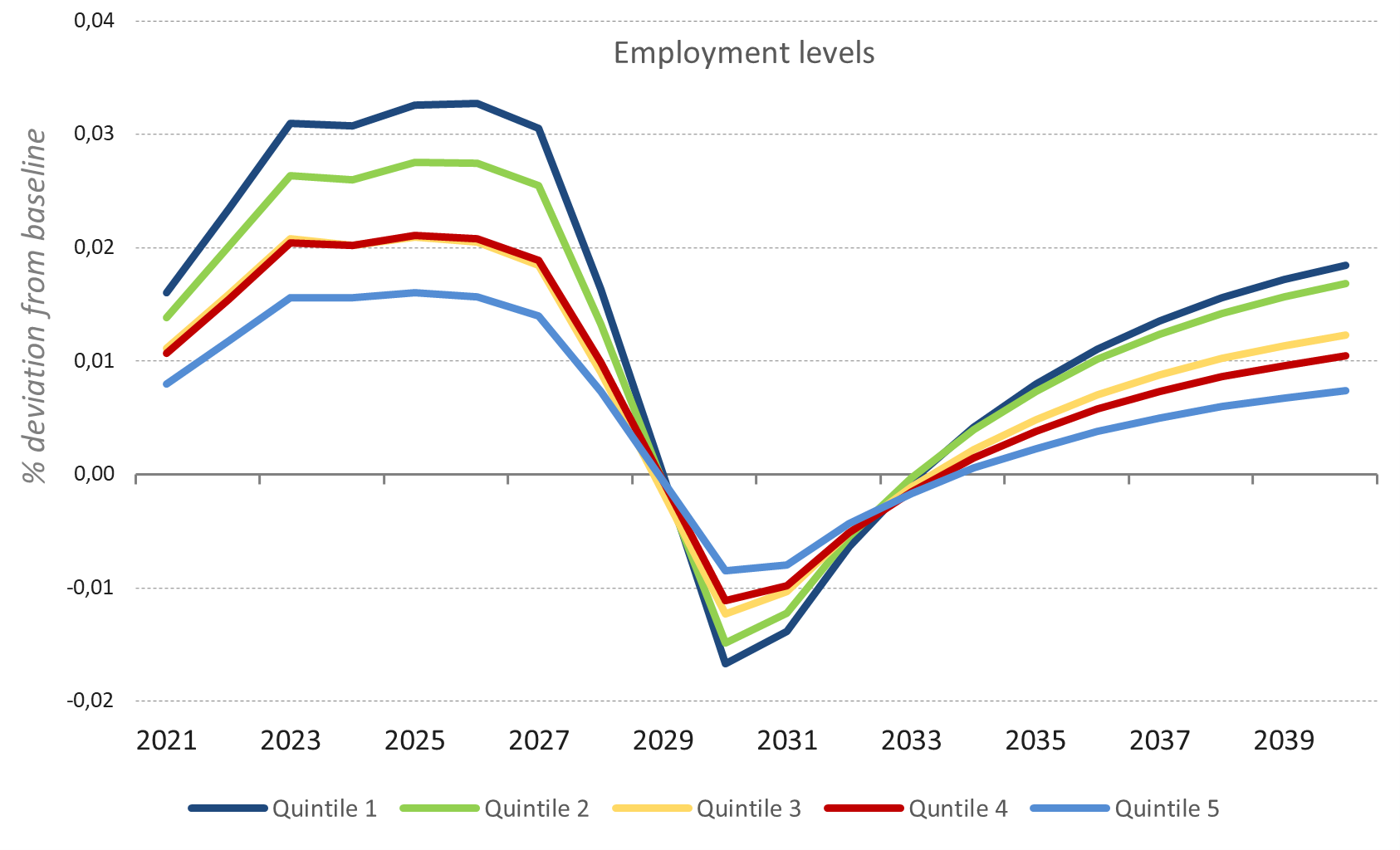

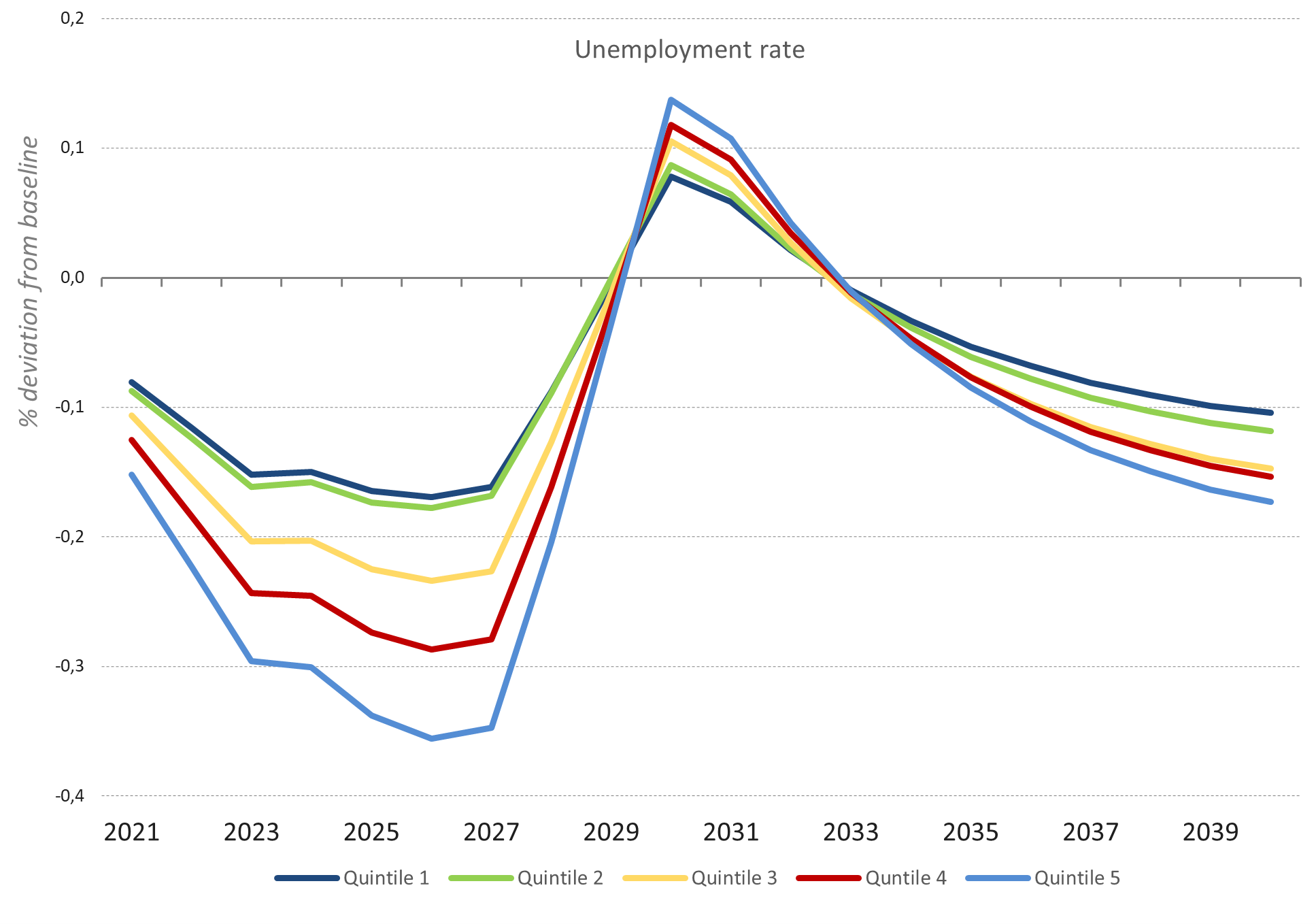

Targeted investments in skills can lead to employment gains throughout the funding period and in the long-term.At their peak in 2026, EU-level employment gains are projected to be 0.024% compared to the baseline scenario of no investment, with the largest employment gains expected for the lowest income quintiles (Chart 3.9). (171) This impact is larger in regions with more significant investments. (172) When the demand stimulus related to the ESF+ funds ends, employment decreases and temporarily dips below its initial level, (173) before recovering and rising above the initial level in the long term. (174) Developments in the unemployment rate mirror these results, with decreases in unemployment rates projected in the short and long term, as vacancies for upskilled individuals who benefitted from the programmes are filled (Chart 3.9).

Chart 3.9

Investment in skills can improve labour market outcomes in the short and long term

Expected EU-level impact of ESF+ investment in labour productivity-enhancing programmes on levels of employment (left) and unemployment rate (right) by income quintile (% deviation from baseline)

Note: Income quintile 5 indicates the richest income quintile and quintile 1 the poorest.

Source: JRC calculations based on RHOMOLO model.

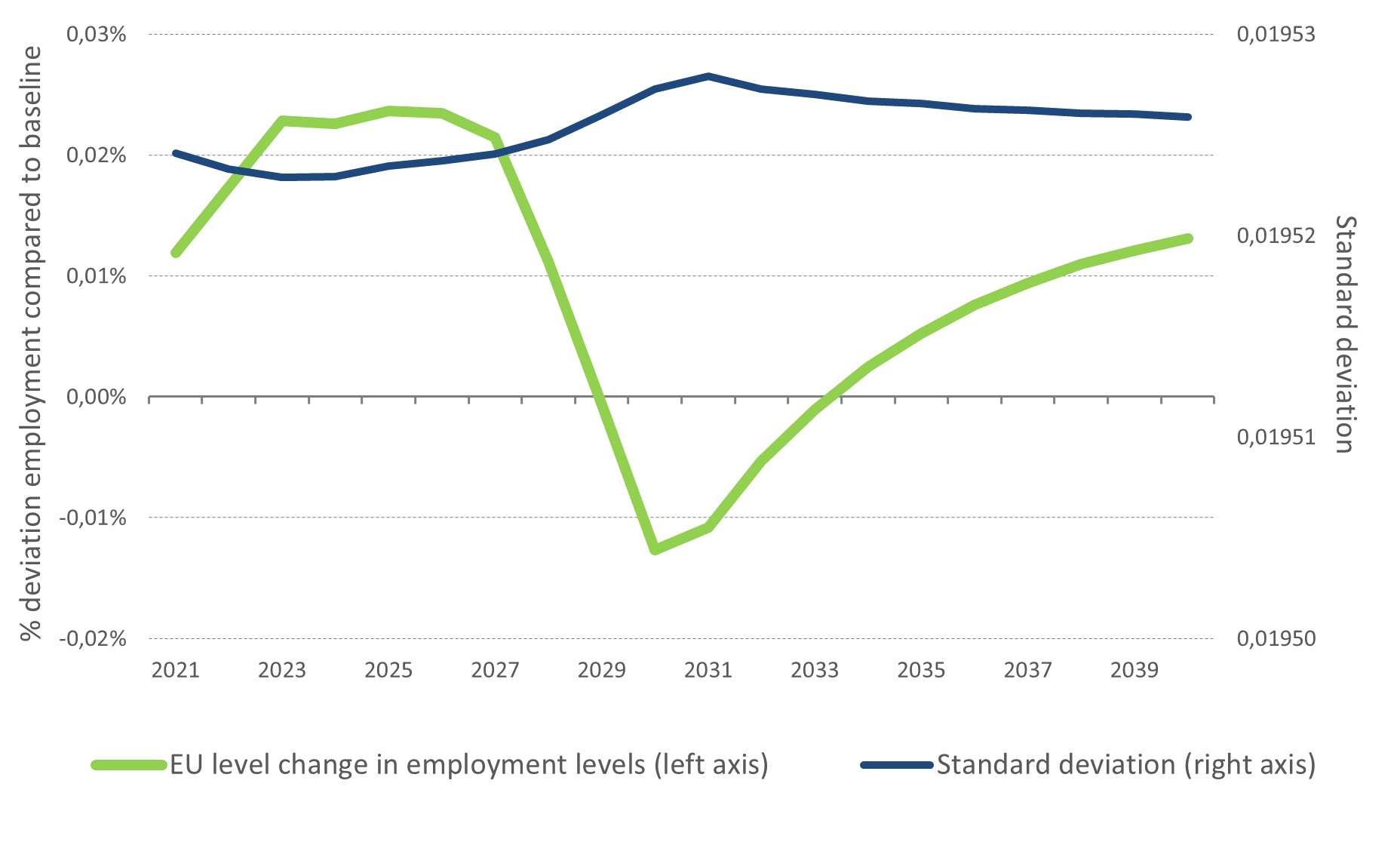

Targeted investment in skills has the potential to contribute to sustained regional economic convergence.The simulation suggests upward convergence in GDP per capita between NUTS2 regions in the EU as a result of the ESF+ 2021-2027 funding period (Chart 3.10). (175)Regions with lower relative GDP per capita are projected to grow more strongly as a result of the funding, catching up with regions with higher initial GDP per capita levels. (176) Despite evidence of regional convergence in employment levels during the funding period, (177) these effects are not sustained in the medium and long term. This could be because of an overall improvement in outcomes in regions not directly receiving ESF+ funding but experiencing positive spillover effects. This is in line with previous analyses showing that improvements in skills-matching in some regions may have positive spillover effects into other regions. (178) These overall improvements would thus limit the potential for convergence across regions (Box A3.1 in the Annex).(179)Individuals might also need to be retrained in the medium to long term in line with changing skills needs, reducing the effect of the intervention in the medium to long term. (180)More generally, the convergence impact of skills-related ESF+ investments on labour market outcomes appears to be limited, as the changes in the standard deviations (as a measure of convergence) are relatively small in scale (Chart 3.10).

Chart 3.10

Investment in skills contributes to upward regional convergence in GDP, with only limited short-term convergence in labour market outcomes

EU-level change in GDP compared to baseline and variation across regions, 2021-2040 (left). Average change in employment levels and variation across regions (right), 2021-2040

Note: Standard deviation is a measure of regional variation, the higher the standard deviation, the higher the regional variation.

Source: JRC calculations based on RHOMOLO model.

Box 3.4: Investments for a fair green transition

Social investment can help to advance the fair green and digital transitions and adapt to demographic change in the EU. This box provides novel evidence on how social investment can support the fair green transition, based on recent findings from the DG EMPL-JRC AMEDI and DISCO(H) project. (1)

Investment needs in the transition towards a climate-neutral economy: policy context

The ambition of the European Green Deal requires massive public and private investment and systemic change, including re- and up-skilling the workforce, changes in business models, and lifestyles. (2) Since its launch in 2019, the EU has set climate targets in law to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by at least 55% by 2030, and the Commission recommended a new 2040 target to reduce GHG net emissions by 90% (both compared to 1990 levels). The Council Recommendation on ensuring a fair transition towards climate neutrality (3) guides Member States to adopt concrete policy packages on quality employment in the green economy, skills and training, social protection, and access to essential services (including affordable housing, energy and transport), and to align investment flows with the investment needs for a just transition.

Investments in decarbonisation, infrastructure, as well as human capital are central to achieving the goals of the European Green Deal. While the importance of social investments linked to the green transition is recognised in the 2020 European Green Deal Investment Plan, human capital and social infrastructure are still underfinanced. Investment needs for retraining, reskilling and upskilling in manufacturing of strategic net-zero technologies alone are estimated at around a total of EUR 3.1 to 4.1 billion by 2030. (4) The EU is currently mobilising investments for a fair green transition through several funding mechanisms, such as the Just Transition Mechanism (EUR 55 billion over 2021-2027), the Social Climate Fund (EUR 86.7 billion over the period 2026-2032), the RRF (EUR 275 billion), (5) and ESF+ (EUR 9.6 billion over the period 2021-2027).

The analysis presented in this box assesses social investment needs related to reskilling and upskilling with a particular focus on the renewable energy sector. To scale up manufacturing of clean technologies (wind, solar, batteries, heat pumps, electrolysers), the European Commission has proposed the Net Zero Industry Act (NZIA). According to the needs assessment accompanying the Act, between 30 000 and 100 000 additional jobs will be created by 2030 to produce wind and solar-related technologies, depending on factors such as specific technologies used, pace of adoption and innovation, scale of investment, and policy frameworks. However, the biggest job creation will be across the value chain: the installation and deployment of wind and solar power generation could lead to about 130 000 to 145 000 additional skilled workers in other sectors by 2030. (6) The main sectors affected by the investment in wind and solar power generation are construction and services, where the bulk of these jobs are concentrated (about 90%). This is followed by the transport sector, where additional jobs come mainly from the infrastructure development for the installation of windmills. According to new estimates, the additional wind and solar capacity to deliver European Green Deal targets may require an investment in skills of EUR 1.1 to 1.4 billion by 2030. Achieving the REPowerEU targets will require the creation of over 3.5 million jobs by 2030. (7)

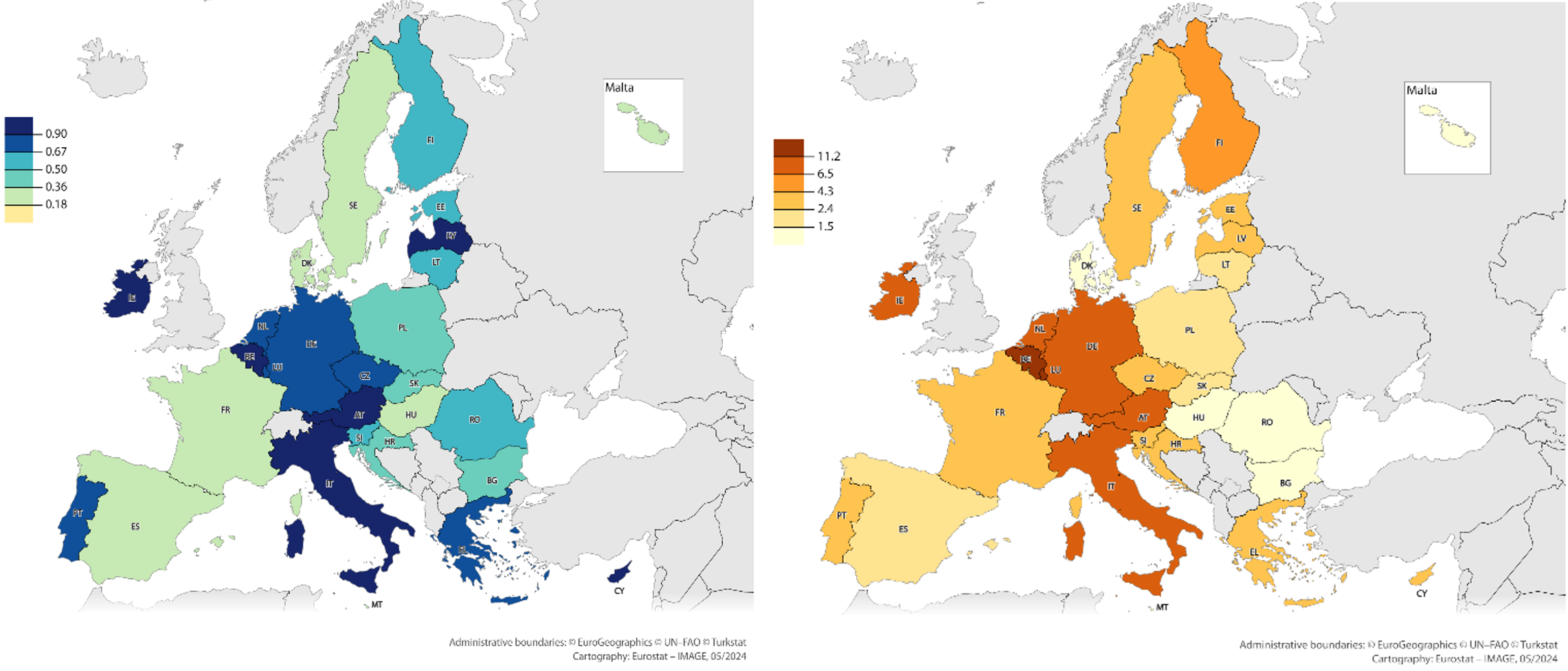

Countries with a higher share of renewables in power generation tend to have lower job creation and training costs associated with the installation and deployment of wind and solar power generation by 2030 and vice versa. Countries such as Belgium, Ireland and Italy need a high number of additional workers, about 1 job created per thousand people in the labour force by 2030, due to the deployment needs of wind and solar power generation (Figure 1, left map). The average share of renewables between 2020 and 2022 (based on Eurostat data) is comparably low for these countries (between 27% and 38%). Conversely, job creation should be close to 0.4 jobs per thousand people in Portugal or Sweden, which have a higher share of renewables (59% and 78%, in wind and solar power generation, respectively). Similarly, Member States with relatively higher installed capacity today show lower (re-)training expenses per person in the workforce, as additional job creation is not as high (Figure 1, right map). For instance, Belgium, Ireland and Italy plan to undergo a catching-up process in wind and solar deployment between 2025 and 2030. Currently, they are exploring their available renewable potential and increasing the share of wind and solar in their energy mix, stimulating the need for different skillsets and tasks in those sectors (e.g. drivers bringing blades for wind power generation to sites).

Figure 1

Job creation and training costs for installation and deployment of wind and solar power generation by 2030 is expected to be more prominent in Member States with a lower share of renewables now

Additional workers needed for installation and deployment of wind and solar power generation by 2030, per thousand people (left map). Training costs (EUR per person) in the labour force in 2030 (right map)

Source: JRC calculations under AMEDI project, based on information from multiple sources (PRIMES and POTEnCIA energy models, EU 2020 Reference scenario (European Commission, 2021), JRC-GEM-E3 model investment matrix for the EU-27 and retraining costs estimates per person per year (European Commission, 2020c); (Vandeplas et al., 2022).

Investing on promoting lifestyle changes and levers to achieve climate neutrality

Beyond investing in human capital, investing in affordable and sustainable mobility, food, energy and housing is also central to achieving climate neutrality in a fair manner. Changes in lifestyles and behaviours are important levers to transition towards a resource-efficient, climate-neutral, and pollution-free circular economy and could help to reduce GHG emissions by 40-70% by 2050. (8) Sustainable lifestyles are ‘a cluster of habits and patterns of behaviour embedded in a society and facilitated by institutions, norms and infrastructures that frame individual choice, in order to minimise the use of natural resources and generation of wastes, while supporting fairness and prosperity for all’.(9)

Reducing the consumption impacts of those contributing most to resource use, pollution and GHG emissions can enable a fair transition. The distributive aspect of the consumption footprint shows that the consumption patterns of higher income groups have larger environmental and climate impacts. Higher income households tend to consume significantly more than other income groups, resulting in higher environmental and climate pressures. The consumption footprint for the 20% of the population with the highest income is 1.8 times higher than the footprint of the poorest 20% in the EU (see Chart A3.2 in Annex). Higher income households have larger environmental and climate impacts due to their mobility and transport choices (22%), as well as from the consumption of household goods and appliances (11%). On the other hand, as poorer households spend a higher proportion of their income on food (54%) and housing-related expenses and particularly energy (25%), measures to encourage and enable more sustainable lifestyles need to keep affordability in mind if they are to avoid having regressive effects. More granular information on the precise types of expenditure within each broad consumption is needed in order to design policies that can foster sustainable lifestyles in a fair manner. In this context, the design of green tax reforms is crucial to ensure that these measures are fair and do not reinforce inequalities.

- 1. See Assessing and Monitoring Employment and Distributional Impacts of the European Green Deal (AMEDI) project here. See Distributional Assessments of the Consumption Footprint of Households in the EU (DISCO(H)) project here.

- 2. The European Green Deal is Europe's policy framework for the transition towards a fair, modern, resource-efficient and carbon-neutral society and economy by 2050.

- 3. (European Commission, 2022b)

- 4. Equivalent to EUR 8 749 to EUR 8 754 per worker (European Commission, 2023b)

- 5. (European Commission). See Recovery and Resilience Scoreboard here.

- 6. (European Commission, 2023b)

- 7. (EurObserv'ER, 2022)

- 8. (Creutzig et al., 2022)

- 9. (Akenji and Chen, 2016)

Notes

- 162.(Hemerijck, 2017).

- 163.(European Commission, 2023b).

- 164.(European Commission, 2019a).

- 165.(Cedefop, n.d.).

- 166.(European Commission, 2023d).

- 167.Greece, Spain, Italy, Romania, Slovakia, Sweden.

- 168.DG EMPL’s LMM is a general equilibrium model that places a special emphasis on labour market institutions.

- 169.Beta coefficient is negative and statistically significant for both unemployment (aged 15-24) and employment (aged 15-24; aged 25-59) rates, respectively. An analysis of the employment rate of 15-64-year-old was not possible due to the age breakdown of the LMM.

- 170.(Christou et al., 2024).

- 171.The lower income quintiles also experience larger increases in real wages compared to the richest income quintile, as their labour productivity increases relatively more.

- 172.For instance, in the Bulgarian region BG31, Severozapaden, and the Portuguese region PT20, Região Autónoma dos Açores, impacts at the peak are +0.195% and +0.185%, respectively.

- 173.The temporary decrease in employment below initial levels stems from modelling specificities. In the model, agents are myopic and make decisions based only on past and current economic conditions. Thus, they cannot anticipate the end of the monetary injection (at the end of the implementation period), nor the full positive impact of the supply-side effects of the policy intervention that will materialise in the future. The combination of positive shocks (increased government spending and increased productivity) and negative shocks (contributions needed to finance the policy) together with the asymmetric nature of the shocks across regions and agents being myopic can lead to a temporary negative effect at the end of the implementation period.

- 174.Despite ESF+ spending of less than 0.1% of EU GDP for each year of the programming period, employment would still be 0.013% higher than the baseline 20 years after the start of the programme.

- 175.The coefficient of variation of the GDP per capita indicator follows a similar decreasing trend to the standard deviation.

- 176.Beta coefficient is negative (-0.008) and statistically significant at 1% significance level, measured at year 10 relative to baseline, and remains negative and significant over the time horizon of the analysis (20 years since the start of the funding period).

- 177.Beta coefficient is negative (-0.0004) and statistically significant at 1% significance level, measured at year 5 relative to the baseline.

- 178.(European Commission, 2023b).

- 179.This finding can be explained through other regions profiting from the increased demand and increased production in regions benefitting from the investment, for example through the provision of intermediate inputs and additional trade dynamics that may improve labour market outcomes in regions not originally affected.

- 180.The immediate effect of the intervention is modelled to depreciate over time.