3. Labour market developments

3.1. Employment trends

Despite ongoing economic challenges, labour markets in the EU remain robust. Alongside modest GDP growth of 0.4% in 2023, employment increased by 1.2% in the EU and 1.4% in the euro area, with 216.5 million people employed in the EU and 168.7 million in the euro area. With the exception of Romania (-0.9% compared to 2022), all countries experienced an increase in employment. The countries with the highest percentage increase were Malta (+6.7 %), Ireland (+3.5%), Estonia (+3.2%), Spain (+3.2%) and Luxembourg (+2.2%). All other Member States recorded a percentage growth below 2.0%. Notwithstanding a rise of 1.0% in total hours worked in the EU (+1.3% in the euro area) in 2023 compared to 2022, there was a slight decrease in the number of hours worked per employed person (-0.2% in the EU and -0.1% in the euro area), still below the pre-COVID-19 pandemic levels in 2019. This downward trend, which has been protracted for the last two decades, may reflect the introduction of more efficient and productive technologies, including the acceleration of digitalisation, as well as changes in work attitudes. After recovering in 2021 and 2022, labour productivity decreased again in 2023 compared to the previous year (-0.8% per employed person and -0.6% per hour), reflecting a combination of higher labour supply and fewer hours worked per employed person, (19) as well as low total factor productivity growth.

In 2023, the sectors that contributed most to employment growth were trade, transport, accommodation and public administration, defence, education, human health and social work activities. The numbers of people employed in these two sectors increased by 0.8 million and 0.7 million, respectively. In relative terms, employment grew most in information and communication (+4.2%), indicating the elevated need for specialised skills. It rose by 0.9% in construction and 0.2% in industry, and declined by 1.1% in agriculture, forestry and fishing. The number of self-employed people increased by 1.0% and employee numbers grew by 1.3%.

Chart 1.4

Number of hours worked per person employed stagnated in 2023 despite a resilient labour market

Left chart: Number of people employed, and number of hours worked (2012=100); Right chart: Headcount employment (% change on previous year), 2012-2025

Note: EA = euro area. European Commission (DG ECFIN) 2023 Spring Forecast in the shaded area.

Source: Eurostat [nama_10_a10_e, nama_10_pe, naida_10_pe], DG ECFIN Forecast.

According to the European Commission Spring 2024 Economic Forecast, employment should expand by 0.6% in the EU in 2024 and by 0.4% in 2025, driven by a positive carry-over effect of gains during 2023. Such expansion could be limited by the fact that employers are retaining their workers in a context of labour shortages (so-called labour hoarding). (20) In July 2024, the new indicator of labour hoarding developed by the Commission increased slightly compared to the previous month (+0.4 pp to 10.8%, three-month moving average), slightly above its long-term average (9.7%) and pre-COVID-19 pandemic levels (7.5%, three month moving average in February 2020) (Chart 1.4). The level was higher in retail (15.5%) and construction (15.3%) and, than in industry (9.7%) and services (8.2%). (21)

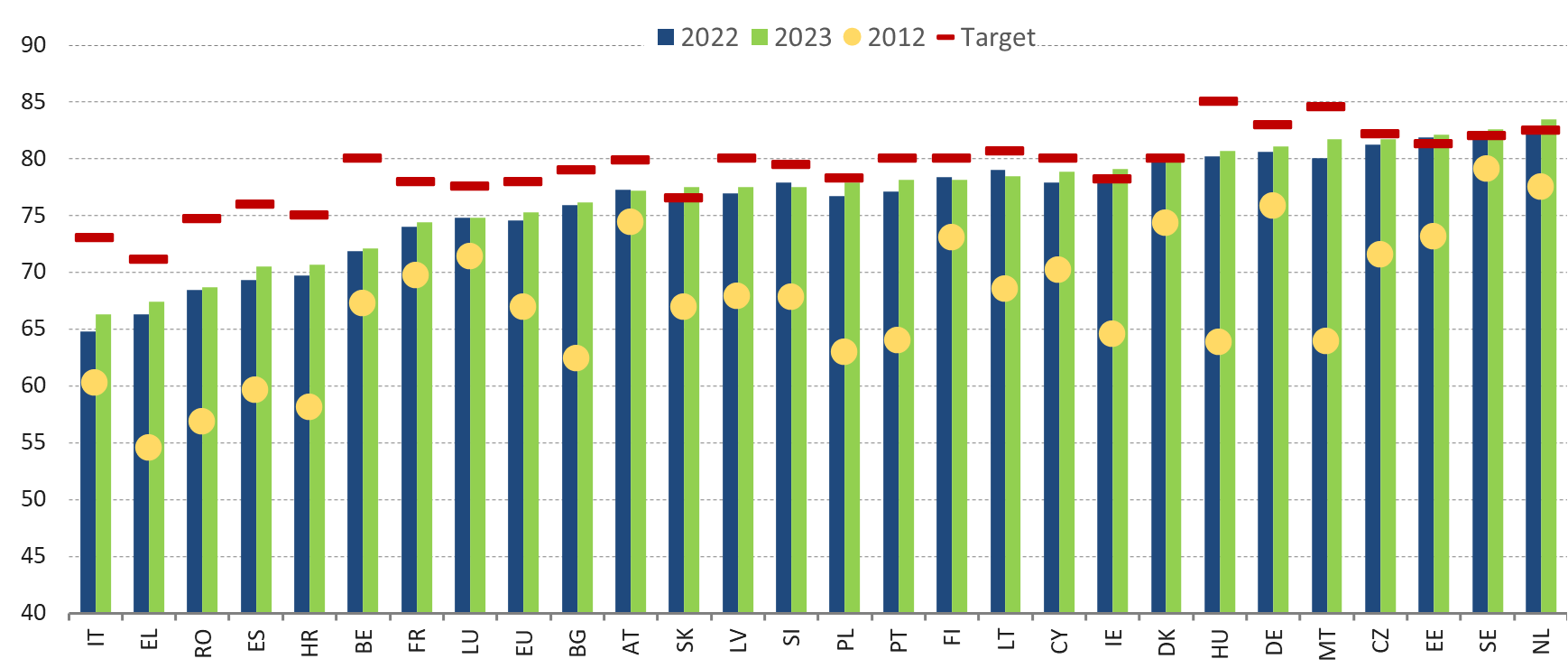

In 2023, the employment rate for individuals aged 20-64 reached the highest recorded levels in the EU. At 75.3%, it corresponded to an increase of 0.7 pp in both the EU and euro area (74.7%) compared to 2022 (Chart 1.5). The 2023 EU employment rate is getting closer to the EU Porto target, which aims to achieve at least 78% of people aged 20-64 in employment in the EU by 2030, with national targets specific to each Member State. The largest increases were recorded in Malta (+1.6 pp), Italy (+1.5 pp), Poland and Spain (both +1.2 pp), while the employment rate declined in Lithuania (-0.5 pp), Slovenia (-0.4 pp), Denmark (-0.3 pp), Finland (-0.2 pp) and Austria (-0.1 pp). Five Member States (Estonia, Ireland, the Netherlands, Slovakia, Sweden) are already above their national target (Chart 1.5).

Chart 1.5

Employment rates reached historic levels in 2023, but growth is slowing

Employment rate (% of people aged 20-64) in the EU and euro area (left) and across all EU Member States (right)

Source: Eurostat [lfsi_emp_a].

The gender employment gap (22) continued to decrease in 2023, albeit slowly, while the employment rate for women surpassed 70% for the first time. Within the EU, the difference in employment between women and men stood at 10.2 pp, a decline of 0.5 pp from 2022 and 1.1 pp from 2019. The employment rate for women rose to 70.2%, while the rate for men rose to 80.4%. Further improvements are necessary to meet the ambition set out in the action plan to implement the European Pillar of Social Rights of at least halving the gender employment gap by 2030 compared to 2019 (11.3 pp).

The employment rate rose for all age groups in 2023, but at a slower pace than in previous years. On a yearly basis, the rate grew by 0.4 pp (to 35.2%) for young workers (aged 15-24), by 0.5 pp (to 82.2%) for prime age workers (aged 25-54) and by 1.7 pp (to 63.9%) for older workers (aged 55-64) (Chart 1.6). Despite the COVID-19 pandemic, over the period 2019-2023, the employment rate for younger workers increased by 1.7 pp. Potentially as a result of several national pension reforms and the entry of more active cohorts in these age groups, the employment rate during that same period rose by 5.3 pp for older workers and by 2.0 pp for prime-age workers during the same period. The gender employment gap was wider for older workers (12.0 pp) than for prime-age workers (10.1 pp) and young workers (4.3 pp).

In 2023, the employment rate rose for people aged 25-54 with lower and medium levels of education. The increase was most notable among those with lower education (+0.8 pp, to 64.1%) while it stagnated for those with tertiary education. Despite the implied reduction in the gap, rates remained highest for those with medium-level vocational education (+0.4 pp, to 84.9%) and those with tertiary education (89.7%), who are typically more likely to have the skills required in the labour market.

High employment disparities exist between the general population and people in vulnerable situations, including non-EU citizens or people with disabilities. The disability employment gap stood at 21.5 pp in 2023. In 2023, the employment rate was 76.2% for national workers aged 20-64 (+0.8 pp compared to 2022), 77.6% for EU mobile workers (+0.6 pp), and 63.0% for non-EU workers (+1.2 pp).

Chart 1.6

Employment rates rose in all population groups

Employment rate by sex, age group, educational attainment level and citizenship (% of population of respective group), EU, 2023

Note: % of population aged 20-64 for all groups, except by educational attainment (% of population aged 25-54). No data for International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) 3-4 GEN and VOC before 2021. ISCED (0-2) less than primary, primary and lower secondary education; ISCED (3-4 GEN) general upper secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary education; ISCED (3-4 VOC) upper secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary education; ISCED (5-8) tertiary education.

Source: Eurostat [lfsi_emp_a, lfsa_ergaedn].

The employment rate in rural regions continued to increase, surpassing 75% for the first time. It is close to the employment rate of the total population at the EU level (75.3%), with differences across Member States.

Increases in the numbers of permanent and full-time workers were the primary reason for the rise in employment. The proportion of temporary employment among individuals aged 15-64 in the EU dropped significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and has not returned to the same levels (23.1 million or 11.6% in 2023, 1.6 pp below the 2019 rate and 0.5 pp lower than in 2022). Comparison of the growth rates of employment (+1.2%) and temporary employment (-3.8%) shows that more people have permanent contracts. The share of part-time workers aged 15-64 in the EU increased by 0.2 pp in 2023 (to 17.8%, or 35.4 million people), still below the 2019 rate (19.4%). The share of workers in temporary (12.8%) and part-time (28.5%) employment remained significantly higher among women than men (10.5% and 8.4%, respectively). The gender gap remained stable in both temporary employment (at 2.3 pp) and in part-time employment (at 20.1 pp). Care duties remain the main reason for part-time employment (21.2%), followed by no full-time job found (19.4%) and education and training (14.2%). The proportion of involuntary part-time employment as a share of total part-time employment further decreased to 19.4% in 2023 (-1.5 pp) following a consistent trend since 2014.

Working conditions have improved over the last decade. The number of workers working long hours decreased by nearly one-quarter compared to 2014, reaching 6.9% in 2023. Similarly, the share of workers with atypical working time was 33.9% in 2023, having decreased by nearly 5 pp over a 10-year period, with only a slight increase in 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The proportion of people working more than one job remained remarkably stable between 2020 and 2023 (3.9%), only a slight decrease since 2013 (-0.3 pp).

Notes

- 18. (European Commission, 2024a)

- 19. (European Commission, 2024a)

- 20. ‘Labour hoarding can be defined as “that part of labour input which is not fully utilised by a company during its production process at any given point in time” (ECB, 2003). Typically, labour hoarding, implying under-utilisation of the workforce, occurs in periods of slack or downturn in economic activity. The rationale for companies not to lay off (redundant) employees in such periods is that (i) dismissing workers usually involves costs, e.g. severance payments, and (ii) recruiting workers once economic activity recovers also entails costs (screening the labour market for candidates, training them, etc.)’. When economic activity picks up again, companies may not hire new workers immediately, but rather rely on the underutilised labour already in the company. The European Commission developed an indicator of labour hoarding, which measures the percentage of managers expecting their firm’s output to decrease, but employment to remain stable or increase, based on the Joint Harmonised EU Programme of Business and Consumer Surveys (BCS) (European Commission, 2023c).

- 21. See Business and Consumer Survey here .

- 22. Difference between the employment rate of women and men aged 20-64.