4. Convergence in labour market outcomes and related attitudes through a gender lens

4.2. Attitudes to women’s work and sharing unpaid work

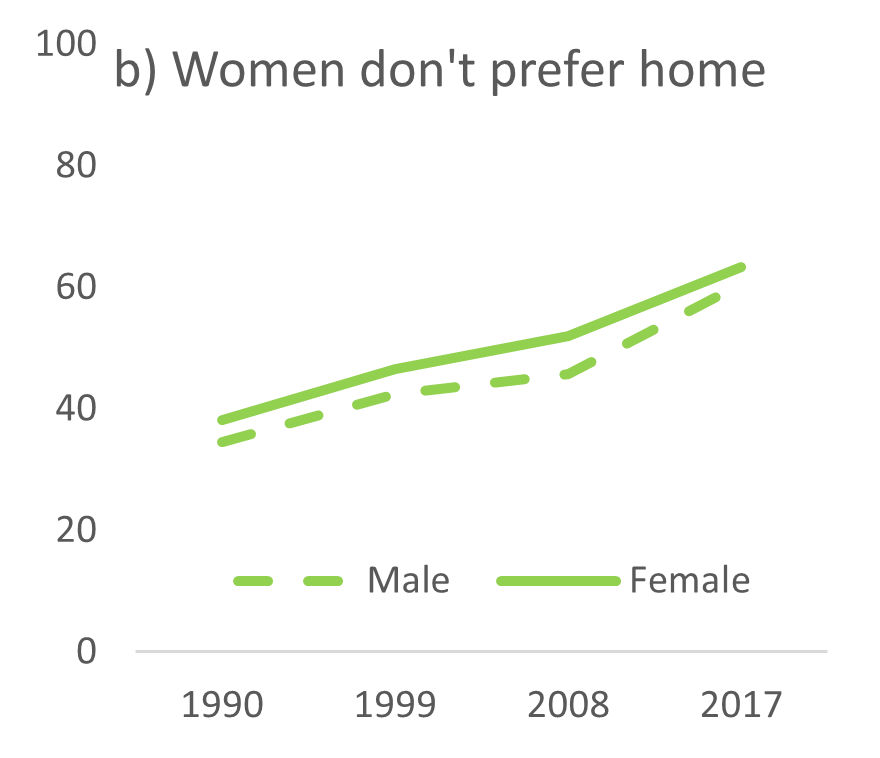

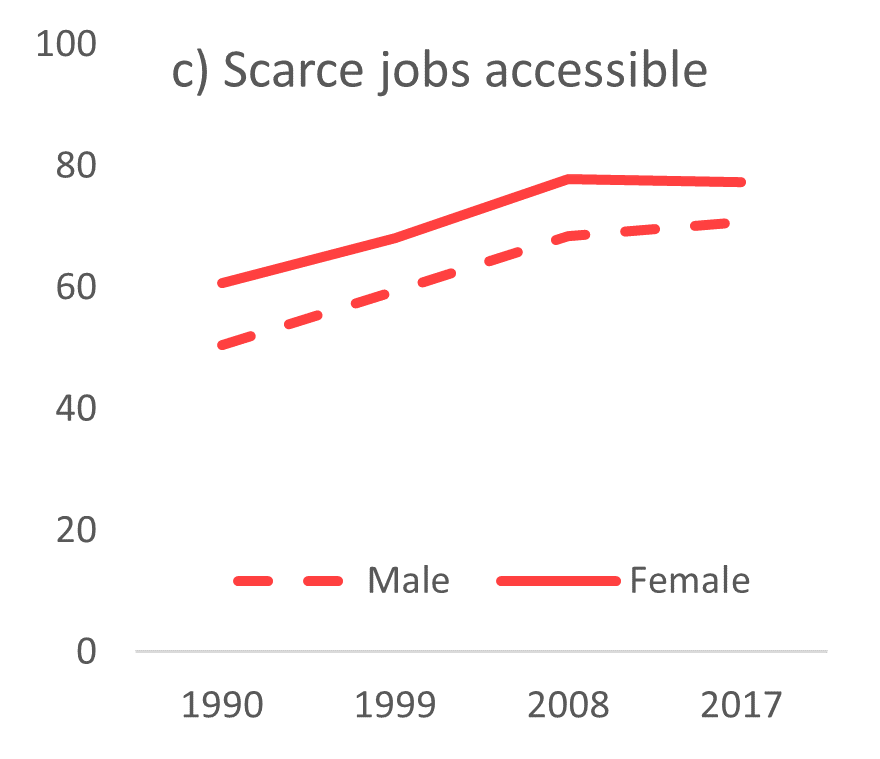

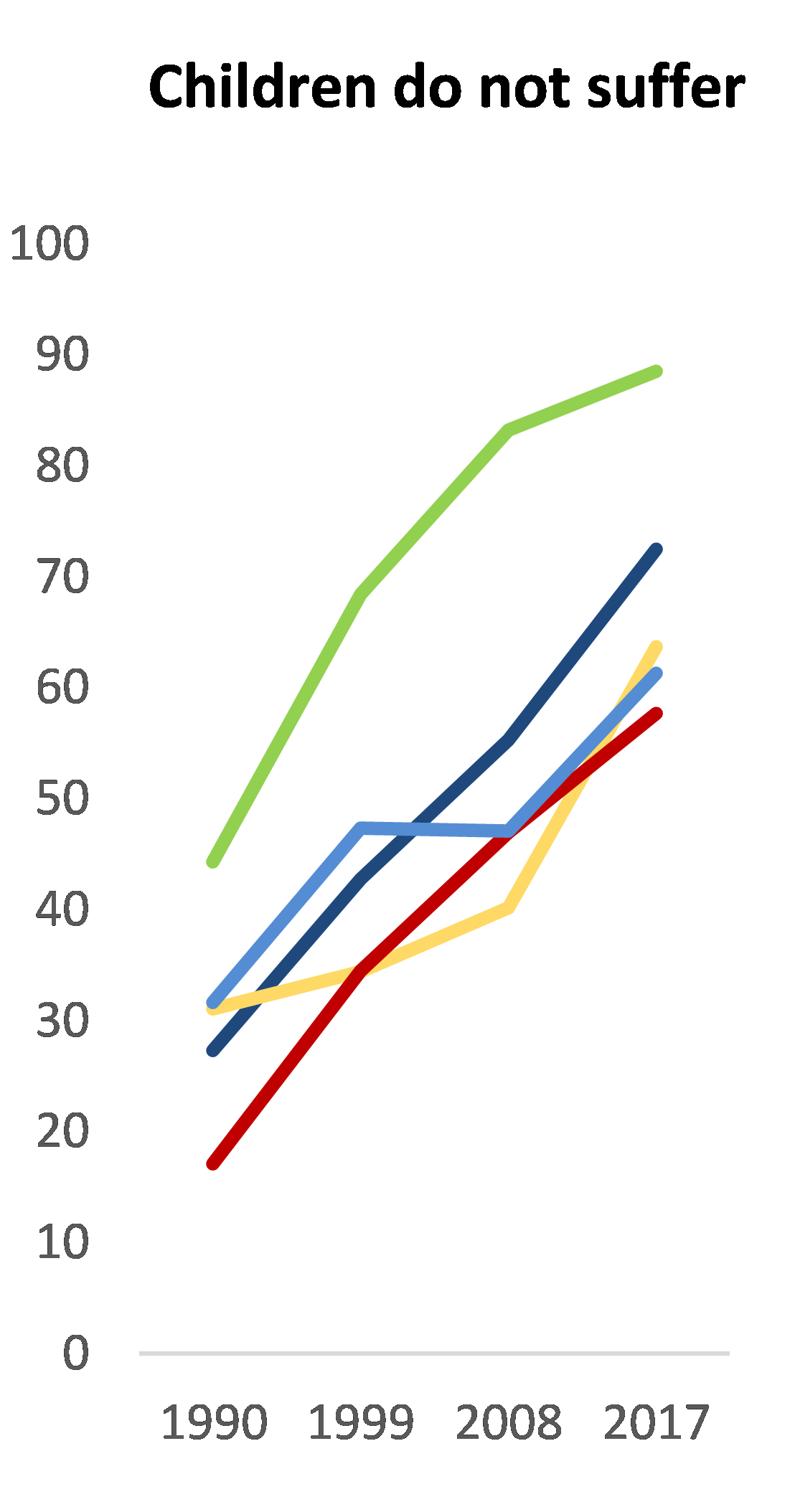

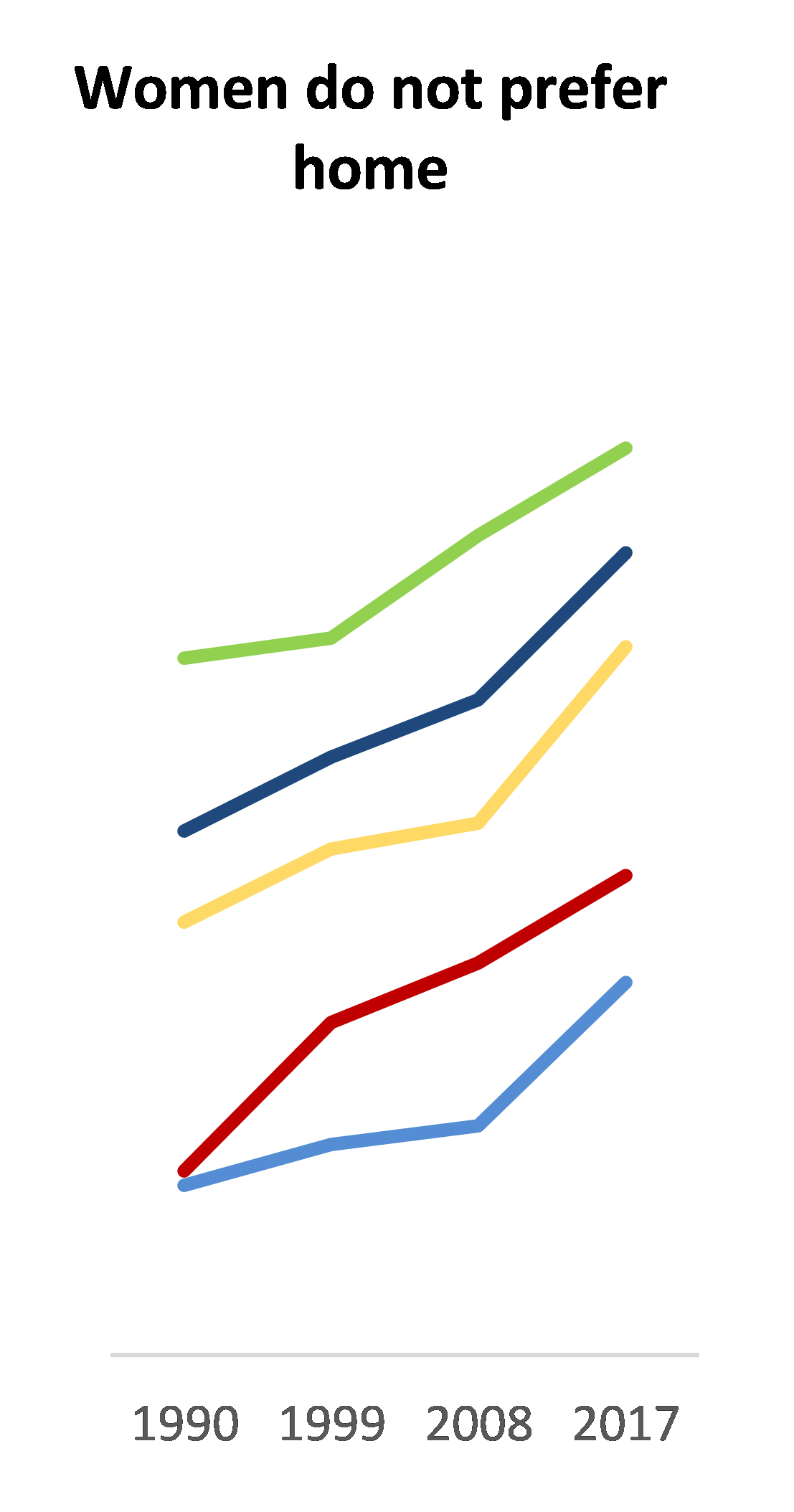

Increasingly positive attitudes to women’s involvement in paid work are consistent with long-term reductions in the gender employment gap. The share of people who do not believe that children suffer when mothers are in paid work increased from less than 40% in 1990 to more than 60% in 2017, with similar proportions among women and men. A comparable increase applies to the share of people who do not consider women to be primarily interested in home and children rather than paid work (Chart 2.11). The proportion of people who oppose preferential access to jobs for men in times of scarcity also increased considerably over the same period, reaching around 75% in 2017 compared to about 55% in 1990.

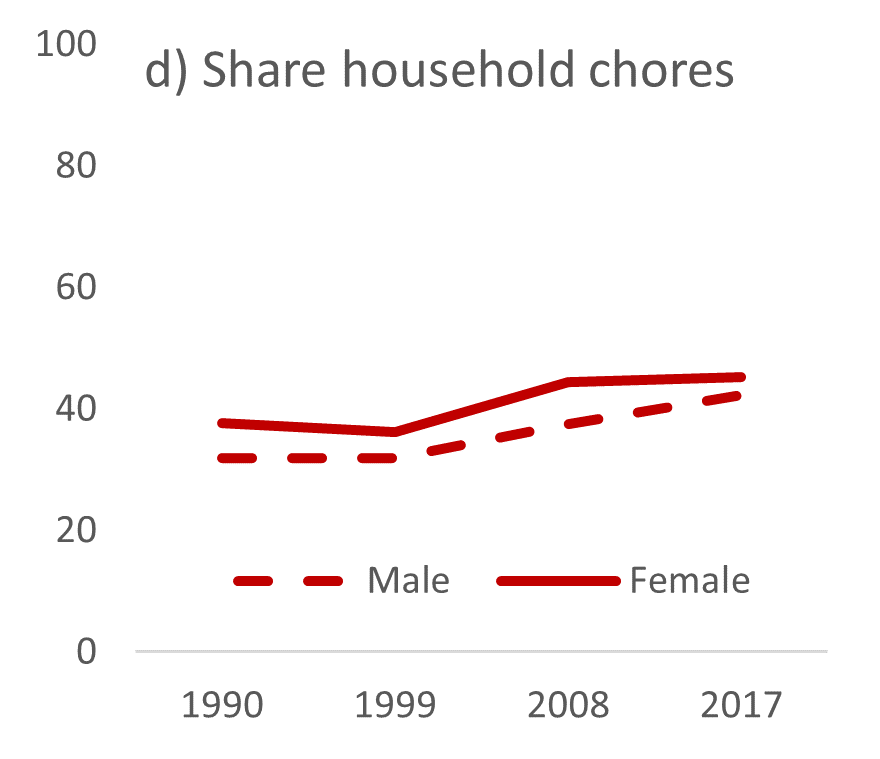

Limited changes in attitudes towards equal sharing of unpaid work pose a challenge to equitable sharing of housework and unpaid care within households. Just over 40% of the EU population believes that sharing household chores is important for a successful marriage or partnership, a minor improvement since 1990 (Chart 2.11). (103) Nevertheless, research shows that sizeable shares of the population hold dual beliefs about women’s roles in society, supporting active roles for women in the labour market while also considering women the primary providers of unpaid work in the household. (104) This belief in women’s role in the household is a persistent challenge to achieving higher employment rates of women.

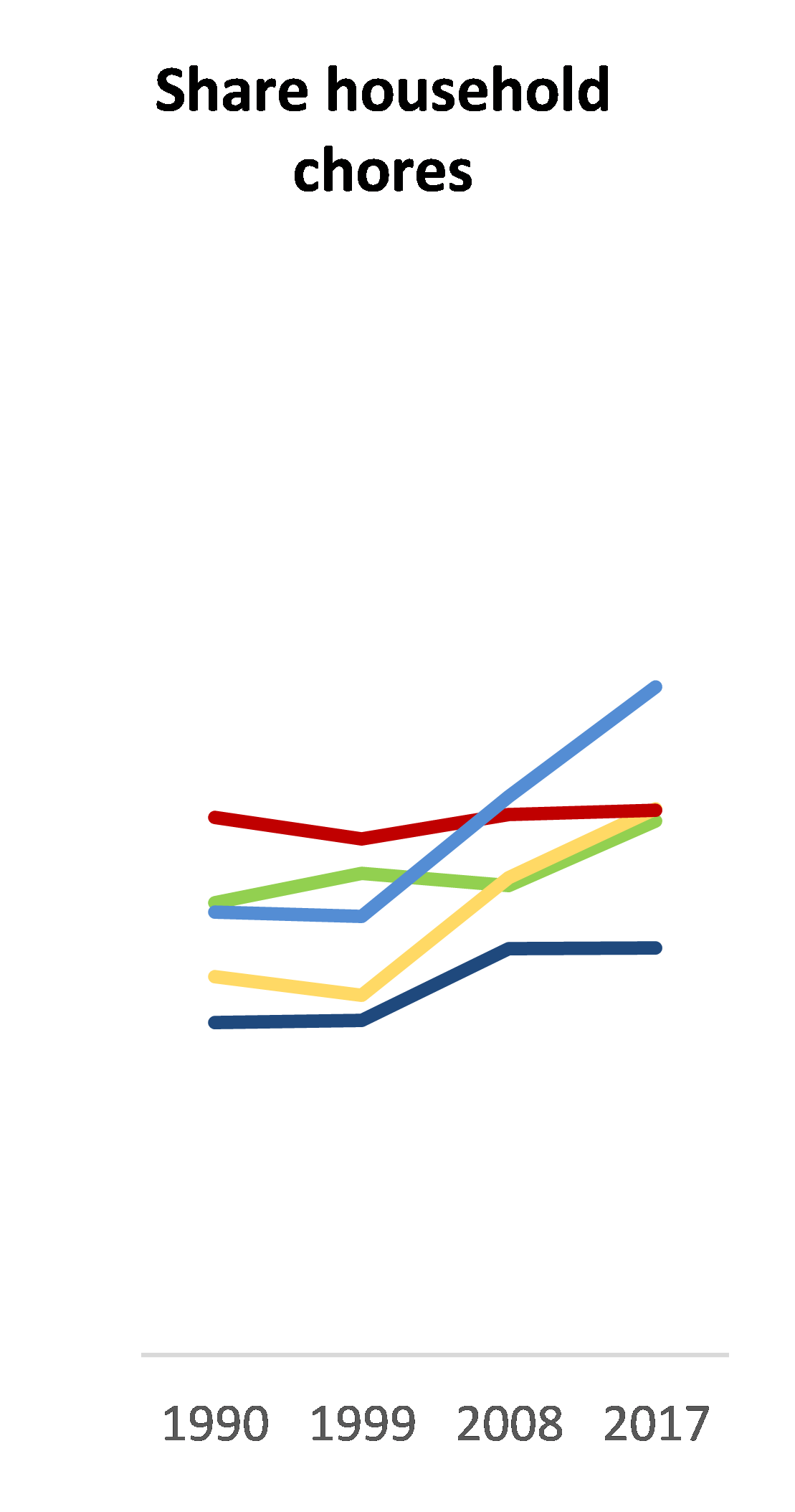

Chart 2.11

Attitudes supporting gender equality in the labour market are more widespread

Proportion of population holding attitudes supportive of gender equality (%) and cross-country variation (standard deviation), 1990-2017, EU

Note: Chart shows the following attitudes: a) Children don’t suffer – share of people disagreeing with the statement ‘When a mother works for pay, the children suffer’; b) Women don’t prefer home – share of people disagreeing with the statement ‘A job is alright but what most women really want is a home and children’; c) Scarce jobs accessible - share of people disagreeing with the statement ‘When jobs are scarce, men have more right to a job than women’; and d) Share household chores – share of people agreeing that sharing household chores is important for marriage or partnership. Data on children don’t suffer missing for Austria in 1999 and data for women don’t prefer home missing for Austria in 1999 and Sweden in 1990. Standard deviation is a measure of cross-country variation, the higher the standard deviation, the higher the cross country variation.

Source: DG EMPL calculations based on European Values Survey data.

Persistent disparities in attitudes between countries complicate convergence towards more gender equal labour market outcomes. Country variation in attitudes to sharing housework and reserving jobs for men in times of scarcity has increased since 1990 (Chart 2.11). This is also the case for variation in attitudes to working motherhood and well-being of children, although cross-country differences dropped sharply after 2008. Cross-country variation in beliefs about women preferring home and children over paid work remain unchanged.

Attitudes supporting gender equality have become more common in the EU since 1990, but differences remain significant. Over 80% of the population of northern Member States agrees that working motherhood is not harmful for children, that women do not prefer children and home over paid work, and that jobs should not be reserved for men in times of scarcity (Chart 2.12). The prevalence of beliefs supporting equality remains lowest in central and eastern Member States, typically ranging from 30% to 60%, which may be linked to the larger gender employment gaps typically observed in some of these countries. By contrast, considering sharing household chores as important is more common in eastern Member States than elsewhere and has become more prominent over the years (from 40% of eastern EU population in 1990 to around 60% in 2017). These finding comes with caveats: firstly, these attitudes only concern housework and not unpaid childcare; and secondly, they do not indicate whether sharing of household chores should be equal between partners. This may be of particular concern in eastern Member States, where beliefs indicating that women prefer taking care of children and staying at home over paid work are common.

Chart 2.12

Considerable and persistent variation in attitudes across the EU

Proportion of population holding attitudes supporting gender equality (%) by country clusters, 1990-2017

Note: Chart shows the following country clusters: west (Austria, Germany, France, the Netherlands); north (Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Sweden); south (Spain, Italy, Portugal); central (Czechia, Hungary, Poland, Slovenia, Slovakia); and east (Bulgaria, Lithuania, Latvia, Romania). Data on ‘children don’t suffer’ missing for Austria in 1999, and data for ‘women don’t prefer home’ missing for Austria in 1999 and Sweden in 1990.

Source: DG EMPL calculations based on European Values Survey data

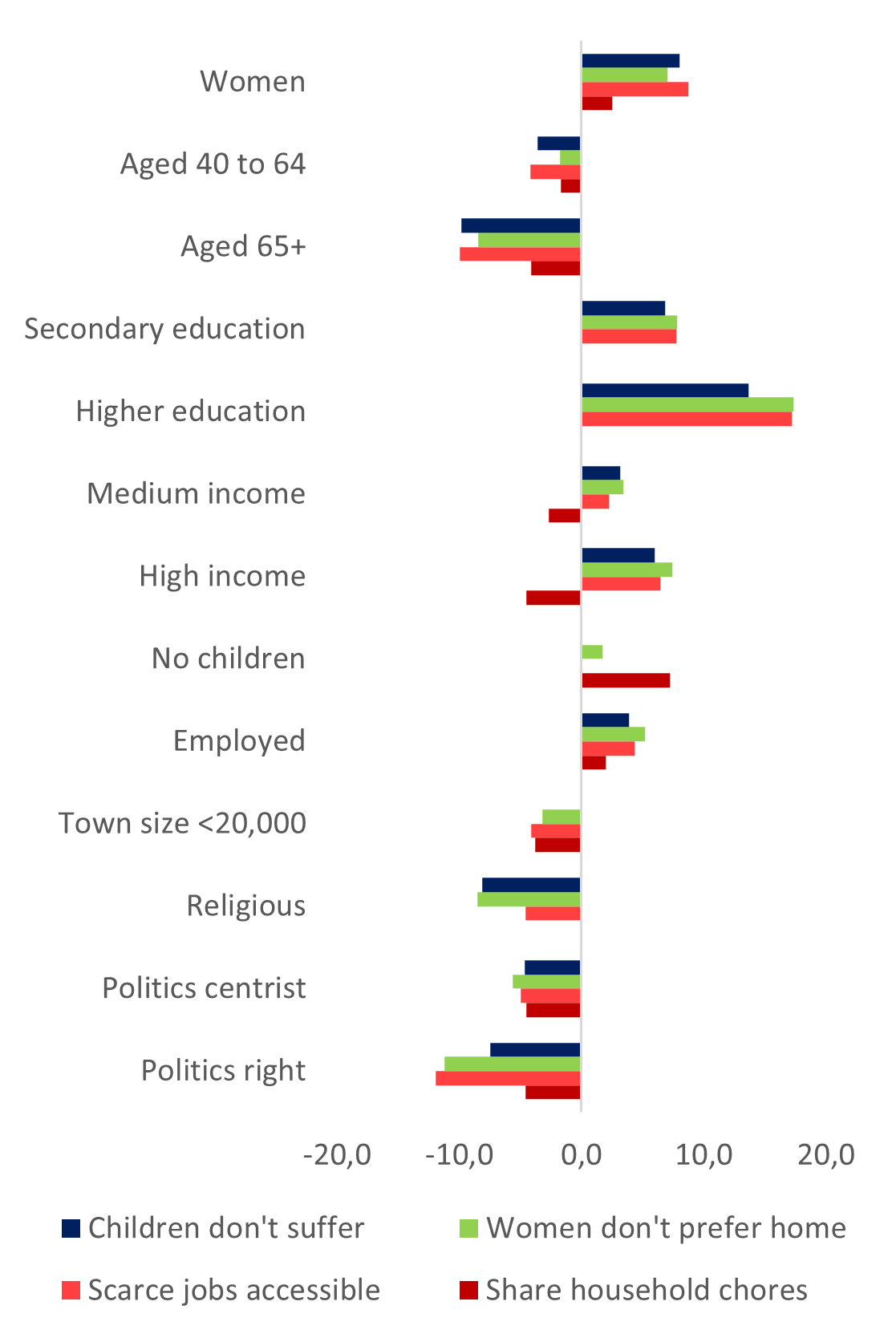

Women and people with higher educational attainment (or incomes) are more likely to support gender equality in the labour market. Over the 1990-2017 period, women in the EU were around 8 pp more likely than men to reject the stereotypes that working motherhood harms children, that women prefer family over paid work and that men have a preferential right to scarce jobs (Chart 2.13). These views were also more common among people with higher educational attainment or (to a lesser extent) higher incomes. For example, those holding tertiary qualifications were around 13-17 pp more likely to report these attitudes than those without upper secondary or tertiary qualifications. At the same time, people who are aged 65+, are religious, or have more traditional voting preferences are more likely to think that working motherhood harms children, and that paid work is valued differently by women and men (Chart 2.13). The differences in attitudes across population groups showed little change over the 1990-2017 period.

Chart 2.13

Attitudes towards women’s position in the labour market vary between population groups

Marginal change in probability of holding a given attitude (pp) by population group, 1990-2017, EU

Note: Probability differences reported against the following comparison groups: gender (men); age (20-39); educational attainment (finished education by 15 years of age); income (lowest income tercile); children (having at least one child); employment status (not in employment); town size (town of 500 000 inhabitants or more); religion (non-religious); political preferences (left-wing). Only statistically significant results (p-value<0.1) reported. Data on children don’t suffer missing for Austria in 1999; data for women don’t prefer home missing for Austria in 1999 and Sweden in 1990.

Source: DG EMPL calculations based on European Values Survey data.

Notes

- 103. Attitudes towards other types of unpaid work (such as childcare) and its sharing by women and men have not been tracked consistently over time.

- 104. The analysis builds on previous research on attitudes in this area, convering earlier developments in the EU context ((Knight and Brinton, 2017); (Grunow, Begall and Buchler, 2018); (Brinton and Lee, 2016); (Scarborough, Sin and Risman, 2019))