EU actions for cross-border healthcare: significant ambitions but improved management required

(pursuant to Article 287(4), second subparagraph, TFEU)

About the report The 2011 Cross‐border Healthcare Directive seeks to ensure EU patients’ rights to access safe and high‐quality healthcare, including across national borders within the EU. These rights are also intended to facilitate closer cooperation between Member States on eHealth and the treatment of rare diseases. We concluded that although EU actions in cross-border healthcare enhance Member States’ collaboration, the benefits for patients were limited. We found that despite the progress made on providing EU citizens with information on cross-border healthcare, in some areas this information remains difficult to access. We identified weaknesses in the Commission’s strategic planning and project management. We make recommendations focusing on the Commission’s support for National Contact Points, the deployment of cross-border exchanges of health data, and EU’s actions in the field of rare diseases.

Executive summary

IWhile cross-border healthcare remains marginal in comparison to healthcare delivered domestically, in some situations, the most accessible or appropriate care for patients is available in a Member State other than their home country. Patients’ ability to make a free and informed choice to access cross-border healthcare can improve their healthcare.

IIThe 2011 Cross-border Healthcare Directive seeks to guarantee EU patients’ right of access to safe and high-quality healthcare across national borders within the EU, and their rights to be reimbursed for such care. The Directive facilitates closer cooperation in a number of areas: notably the cross-border exchange of patients’ data and access to healthcare for patients with rare diseases.

IIIApproximately 200 000 patients a year take advantage of the systems put in place under the Directive to receive healthcare treatments abroad: less than 0.05 % of EU citizens. In recent years, France reported the highest number of outgoing patients and Spain the highest number of incoming patients. The majority of patient mobility has been between neighbouring Member States.

IVWe examined whether the Commission has overseen the implementation of the Directive in the Member States well and provided guidance to the National Contact Points responsible for informing patients about their right to cross-border healthcare. We assessed whether the results achieved for cross-border exchanges of patients’ data were in line with expectations and demonstrated benefits to patients. We also examined key recent EU actions in the field of rare diseases focusing on the creation of the European Reference Networks. These networks seek to share knowledge, provide advice on diagnosis and treatment through virtual consultations between healthcare providers across Europe, and thus raise standards of care.

VWe conclude that while EU actions in cross-border healthcare enhanced cooperation between Member States, the impact on patients was limited at the time of our audit. These actions are ambitious and require better management.

VIThe Commission has overseen the implementation of the Cross-border Healthcare Directive well. It has guided the National Contact Points towards providing better information on cross-border healthcare, but there remains some scope for improvement.

VIIAt the time of our audit, no exchanges of patients’ data between Member States had taken place and no benefits to cross-border patients from these exchanges could be demonstrated. The Commission did not establish an implementation plan with timelines for its new eHealth strategy and did not estimate the volumes of potential users before deploying the cross-border health data exchanges.

VIIIThe concept of European Reference Networks for rare disease is widely supported by EU stakeholders (patients’ organisations, doctors and healthcare providers). However, the Commission has not provided a clear vision for their future financing and how to develop and integrate them into national healthcare systems.

IXBased on our conclusions, we make recommendations focusing on the Commission’s support for National Contact Points, the deployment of cross border exchanges of health data, and EU’s action in the field of rare diseases.

Introduction

01The Cross-border Healthcare Directive (“the Directive”)1:

- sets out EU patients’ rights to access safe and high-quality healthcare across national borders within the EU, and their rights to be reimbursed for such healthcare;

- establishes National Contact Points to provide citizens with information on their rights to cross - border healthcare;

- seeks to facilitate closer cooperation on eHealth, including cross-border exchanges of patients’ data and

- seeks to facilitate patients’ access to healthcare for rare diseases, notably by the development of European Reference Networks (ERNs).

Patients’ rights to cross-border healthcare

02Healthcare is a national competence and Member States finance, manage and organise their health systems2. The Directive sets out the conditions under which a patient may travel to another EU country to receive planned medical care which will be reimbursed under the same conditions as in their Member State. It covers healthcare costs, as well as the prescription and delivery of medications and medical devices, and complements the legal framework already set out in the EU Regulation on the coordination of social security systems3 (see Annex I for the comparison of patients’ rights under the Directive and the Regulation). The Directive aims to facilitate access to safe and high-quality cross-border healthcare based on the free and informed choice of patients, as in some situations, the most accessible or appropriate care for patients is only available in a Member State other than their home country. However, the Directive does not encourage patients to receive treatment abroad.

03Patients seeking to receive healthcare in another Member State are entitled to relevant information on standards of treatment and care, on reimbursement rules and on the best legal pathway to use. Each National Contact Point should provide this information. Member States can require prior authorisation for certain types of healthcare, mainly for treatment which involves either an overnight hospital stay or the use of highly specialised infrastructure or equipment. They do so in around 1 % of cases.

04The Directive confirms that patients seeking healthcare abroad should be reimbursed for that healthcare by their home country, provided that they are entitled to that healthcare at home. The level of reimbursement for treatment abroad is set at the level of cost that would have been incurred by the home country. The requirement for upfront payment by patients, while intrinsic to the design of the Directive, is widely recognised as a significant challenge that patients face4. However, the Directive offers the option for Member States to provide patients with an estimate of healthcare costs.

05The number of citizens claiming reimbursement for medical care received abroad under the Directive is low (approximately 200 000 claims a year – fewer than 0.05 % of EU citizens) compared to those making use of the Regulation on the coordination of social security systems (approximately 2 million claims a year for unplanned treatments abroad). Expenditure on cross-border healthcare incurred under the Directive is estimated at 0.004 % of the EU-wide annual healthcare budget5. A 2015 Eurobarometer survey reported that fewer than 20 % of citizens were aware of their rights regarding cross-border healthcare. The Commission has no recent data on the awareness of citizens regarding the Directive.

06The use of the Directive varies among the Member States. For cross-border healthcare services not requiring prior authorisation, France had the greatest number of outgoing patients (close to 150 000 patients in 2016), with Spain, Portugal and Belgium treating the highest numbers of incoming patients6. Table 1 shows patient mobility in all EU and EEA countries under the Directive in 2016, which covers both cross-border healthcare services and products. The numbers include patient mobility for both, treatments not requiring Prior Authorisation (in total 209 534 patients) and those requiring Prior Authorisation (in total 3 562 patients).

Table 1 – Patient mobility under the Directive in 2016

| Outgoing patients in 2016 | |

|---|---|

| Country | Number of patients |

| FRANCE | 146 054 |

| DENMARK | 25 343 |

| FINLAND | 11 427 |

| NORWAY | 10 301 |

| POLAND | 8 647 |

| SLOVAKIA | 6 110 |

| SLOVENIA | 1 835 |

| UNITED KINGDOM | 1 113 |

| IRELAND | 791 |

| CZECHIA | 401 |

| LUXEMBOURG | 277 |

| ITALY | 201 |

| CROATIA | 200 |

| ROMANIA | 130 |

| ESTONIA | 80 |

| ICELAND | 53 |

| BELGIUM | 30 |

| LATVIA | 27 |

| LITHUANIA | 19 |

| CYPRUS | 13 |

| SPAIN | 11 |

| GREECE | 10 |

| AUSTRIA | 9 |

| BULGARIA | 5 |

| PORTUGAL | 5 |

| MALTA | 4 |

| GERMANY | no data |

| HUNGARY | no data |

| NETHERLANDS | no data |

| SWEDEN | no data |

| Total | 213 096 |

| Incoming patients in 2016 | |

|---|---|

| Country | Number of patients |

| SPAIN | 46 138 |

| PORTUGAL | 32 895 |

| BELGIUM | 27 457 |

| GERMANY | 27 034 |

| LUXEMBOURG | 12 530 |

| CZECHIA | 12 300 |

| ESTONIA | 10 044 |

| ITALY | 9 335 |

| POLAND | 6 545 |

| SWEDEN | 6 162 |

| GREECE | 5 639 |

| HUNGARY | 4 169 |

| AUSTRIA | 2 437 |

| CROATIA | 1 680 |

| NETHERLANDS | 1 653 |

| UNITED KINGDOM | 1 646 |

| ROMANIA | 1 003 |

| BULGARIA | 686 |

| IRELAND | 674 |

| MALTA | 463 |

| FINLAND | 403 |

| FRANCE | 371 |

| LITHUANIA | 369 |

| NORWAY | 327 |

| SLOVAKIA | 259 |

| CYPRUS | 254 |

| DENMARK | 198 |

| LATVIA | 167 |

| ICELAND | 141 |

| SLOVENIA | 117 |

| Total | 213 096 |

Source: ECA based on Report on Member State data on cross-border patient healthcare following Directive 2011/24/EU – Year 2016 available on the Commission’s website.

07The Commission supports cross-border cooperation in healthcare by means of numerous studies and initiatives, including via Interreg7, funded under the European Structural and Investments Funds. Member States are responsible for managing their health systems, and for any cooperation arrangements between Member States. Such cooperative arrangements often develop without the involvement of the Commission. The recent Commission study on activities and EU investment in cross-border cooperation in healthcare identified 423 EU-funded projects8 in support of cross-border collaboration initiatives in healthcare in the period from 2007 to 2017.

Cross-border exchanges of health data

08The Directive mandates the Commission to support Member States cooperation on eHealth and establishes a voluntary network of Member State authorities (eHealth Network) to support the development of common standards for transferring data in cross-border healthcare. eHealth is also a key part of the European Commission’s Digital Single Market strategy and its development in the EU is structured around the actions listed in the Commission’s Actions Plans for eHealth and in the 2018 strategy on eHealth9. The Commission also launched a Task Force in 2017 which is examining incentives and obstacles to achieve secure exchange of health data across the EU.

09The Commission, together with the Member States, is building an EU-wide voluntary eHealth Digital Service Infrastructure (eHDSI), to enable the exchange of patients’ health data – specifically ePrescriptions and Patient Summaries – across national borders. This project involves 22 Member States10 and aims at connecting their eHealth systems to the EU eHealth Infrastructure through a dedicated “portal” known as the National Contact Point for eHealth (NCPeH) (see Figure 1 showing the procedure for cross-border exchange of ePrescriptions).

Figure 1

Cross-border exchange of an ePrescription

Source: ECA.

In some Member States11, the use of ePrescriptions is common. Other Member States however have only recently started to pilot or implement ePrescriptions services. Reduced availability of eHealth services at national levels is one of the main challenges associated with the deployment of the EU-wide eHealth Infrastructure. In addition some Member States do not participate at all (e.g. Denmark – see Box 1 on eHealth applications for patients) or only participate in some of the services of the EU-wide eHealth Infrastructure.

Box 1

eHealth applications for patients in Denmark

The national eHealth portal – Sundhed.dk (https://www.sundhed.dk) allows Danish patients to access their medication profiles, view scheduled consultations with healthcare providers, and re-order certain medication themselves. In 2018, the Danish authorities were working on a pilot project to add further features to the eHealth portal so as to make it easier for patients who consult the doctor frequently (e.g. for chronic disease patients) to schedule their appointments.

In addition, the “Medicinkortet” mobile application allows patients to request an extension for their existing digital prescriptions. All medical prescriptions issued in Denmark are digital.

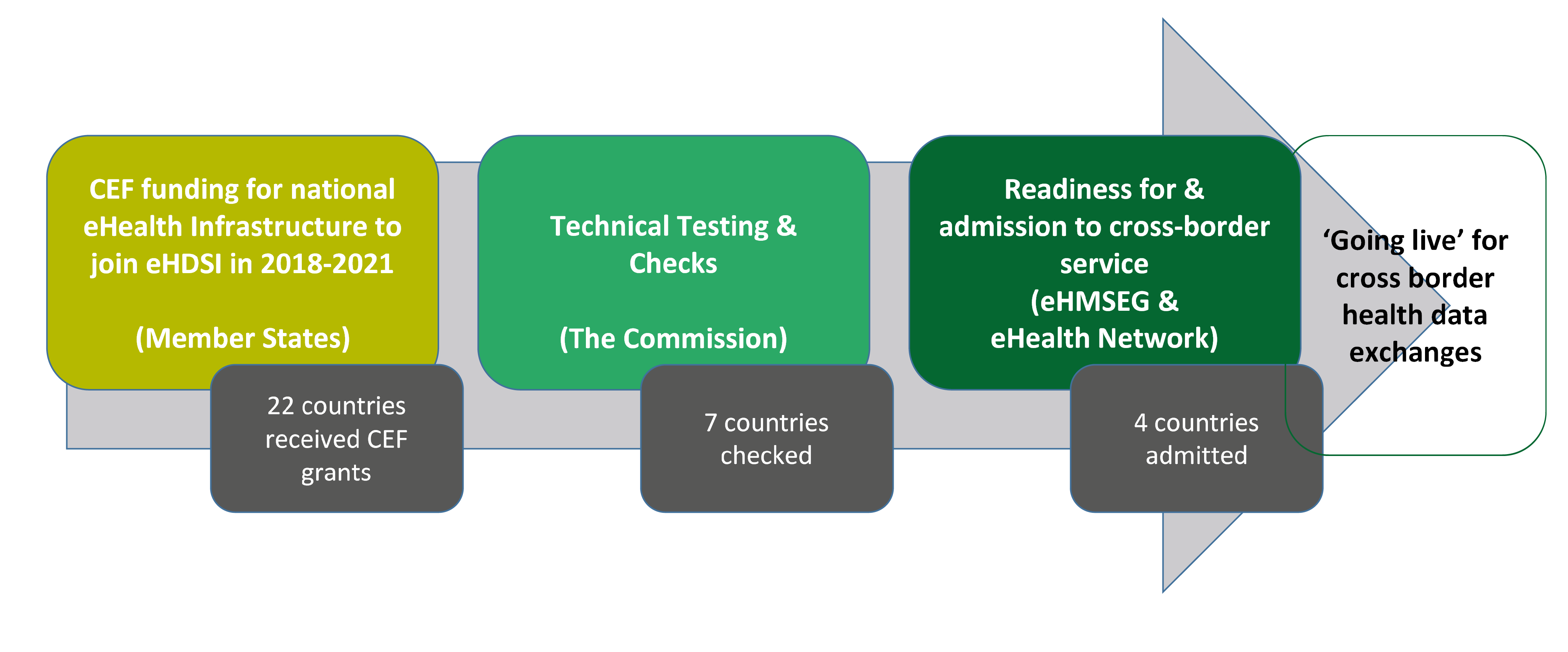

The EU finances eHealth Infrastructure through the Connecting Europe Facility building on a pilot project for cross-border exchanges of health data12. Member States that wish to start cross-border exchanges of health data need to go through a testing and auditing process following which a Member States Expert Group (eHMSEG) makes a recommendation. The eHealth Network then takes a final decision on which countries can ‘go live’ in cross-border health data exchanges.

Cross-border initiatives for rare disease patients

12The Directive defines a rare disease as any disease affecting fewer than five people in 10 000. An estimated 6 000 to 8 000 rare diseases affect between 6 % and 8 % of the EU population, i.e. between 27 and 36 million people. The specificities of rare diseases – a limited number of patients and a scarcity of relevant knowledge and expertise – led the Council of the European Union to single out cooperation in this field as “as a unique domain of very high added value of action at Community level”13.

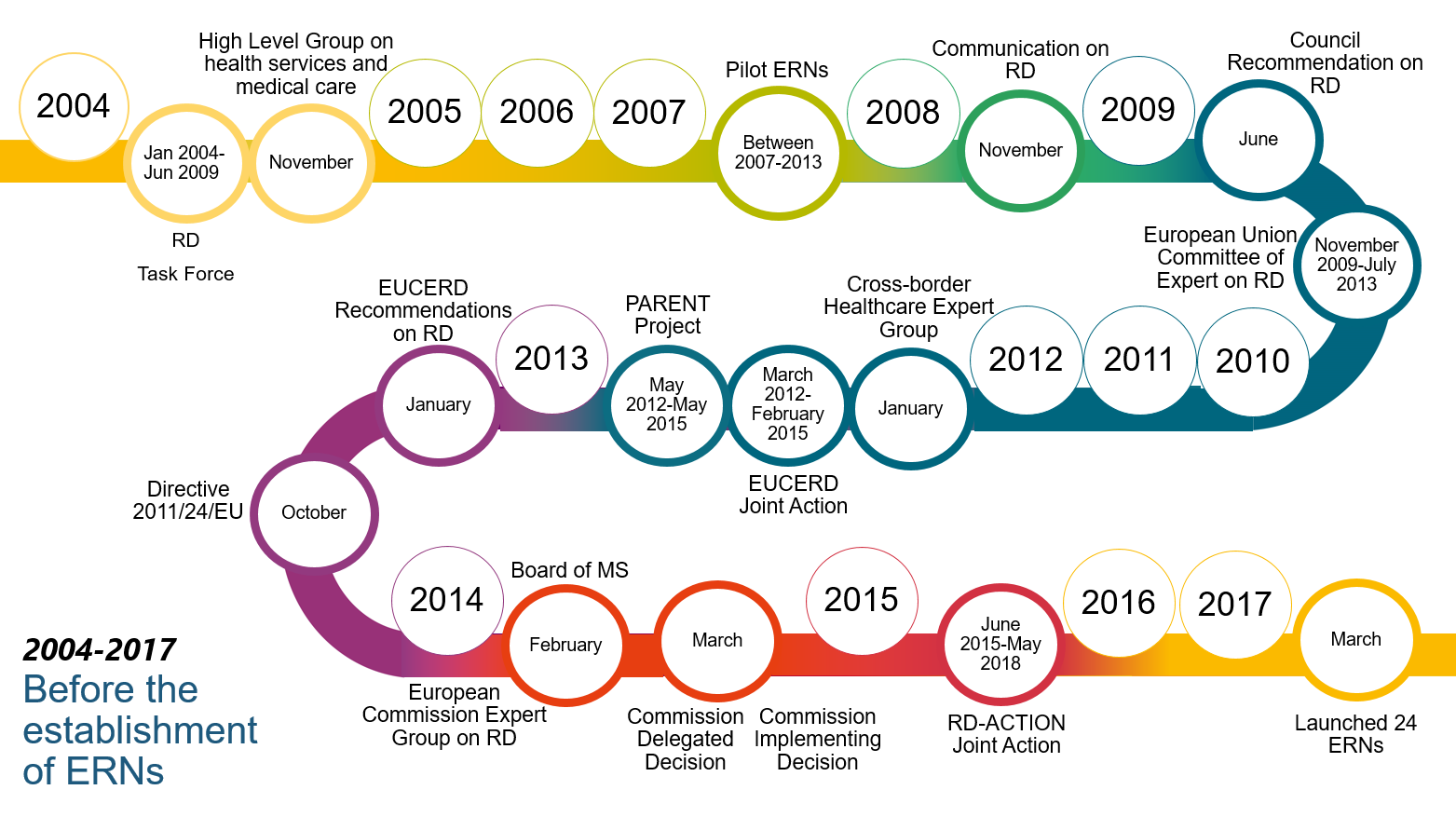

13The Commission put forward a specific policy framework to tackle rare diseases, notably through the creation of the European Reference Networks, in its 2008 Communication “rare diseases: Europe’s challenge”. The Directive mandates the Commission to support the Member States in the development of the ERNs. Figure 2 shows successive policy developments leading to their establishment.

Figure 2

Successive policy developments leading to the establishment of the European Reference Networks

Source: ECA.

The ERNs are intended to reduce time to diagnosis and improve access to appropriate care for rare disease patients and provide platforms for the development of guidelines, training and knowledge sharing. 24 Networks were launched in 2017 for different classes of rare diseases. Each receives €1 million funding over five years from the EU Health Programme. The Commission also finances patient registries and support activities for the ERNs as well as the development of IT tools, notably through the Connecting Europe Facility (CEF).

15When a patient case is referred to an ERN, a “virtual” panel of medical experts is convened via the Clinical Patient Management System (CPMS), a web-based application provided by the Commission in November 2017. The application enables doctors to share information, data and images on individual patients, subject to their consent, and to get support in the diagnosis and treatment. 73 % of ERN members had registered to use the application and 333 panels had been created by December 2018 (see Box 2 showing examples of rare disease patients’ cases consulted by the ERNs).

Box 2

Examples of a rare disease patients cases consulted by a European Reference Network

In 2018, the ERN for Paediatric Cancer was presented with cases concerning two Lithuanian children with rare paediatric cancer. Following advice received from specialists via the ERN, new treatments were provided to these children.

In 2017, the ERN for Rare and Complex Epilepsy was presented with the case of a

In both cases, the ERNs provided valuable advice on patient treatment.

The Board of Member States for ERNs14 approves the creation and membership of the Networks. By the end of 2018 there were 952 healthcare providers (i.e. institutes, hospital units) in over 300 hospitals participating in the ERNs, spread out over the EU. No ERN covered more than 19 Member States. Figure 3 shows that the distribution of healthcare provider members of the ERNs varies across the EU. The highest number of HCPs participating in the ERNs comes from Italy. This Member State has a longstanding national strategy for rare disease actions and a national network of specialised hospitals and centres qualified to assist patients with rare diseases.

Figure 3

Distribution of healthcare provider members of European Reference Networks across the EU

Source: ECA based on data on health care provider members to European Reference Network per Member State provided by the Commission, February 2019.

Audit scope and approach

17One of the strategic goals of the European Court of Auditors (ECA) is to examine performance in areas where EU action matters to citizens15. Improving Europe's health infrastructure and services and their accessibility and effectiveness is an area in which EU action can add value for EU citizens. We launched our audit 10 years after the Commission approved its strategy on rare diseases and the main EU pilot project for cross-border exchanges of healthcare data started. Our audit sought to answer the following question:

Do EU actions in cross-border healthcare deliver benefits for patients?

18We examined whether:

- the Commission oversaw the implementation of EU cross-border healthcare Directive in the Member States well;

- the results achieved so far in terms of cross-border exchanges of health data are in line with expectations;

- EU actions on rare diseases add value to Member States efforts to facilitate patients’ access to cross-border healthcare.

Our audit covered the period from the adoption of the Commission’s rare disease strategy and the launch of the EU’s main pilot project for cross-border exchanges of health data in 2008. We performed the audit work between February and November 2018 and held interviews with the Commission representatives form Directorate-General for Health and Food Safety (DG SANTE), Directorate-General for Communications Networks, Content and Technology and Directorate-General Joint Research Centre (DG JRC) and with five Member States’16 authorities responsible for implementing the Directive. Our choice of Member States considered the main EU funded projects for cross-border exchanges of health data.

20We also surveyed all Member States’ representatives in the Cross-border Healthcare Expert Group to obtain their opinions on main developments and challenges hampering patients’ access to cross-border healthcare and representatives of the eHealth Network on their opinion on the Commission’s work on cross-border exchanges of patients’ data. We received 15 responses from the Cross-border Healthcare Expert Group and 10 from the eHealth Network.

21We audited EU funded projects which aimed to facilitate access to cross-border healthcare, including those for exchanging health data across borders and for developing and maintaining the European Platform on Rare Diseases Registration. We organised an Expert Panel to obtain independent advice on the EU’s rare disease policy and the European Reference Networks.

Observations

The Commission has ensured that the EU Cross-Border Healthcare Directive has been put into practice

22In order to oversee the implementation of the Directive, the Commission needs to monitor and enforce its transposition by the Member States through completeness and compliance checks. The Commission also has to report on the operation of the Directive and appropriately guide the National Contact Points responsible for provision of information to patients on cross-border healthcare.

The Commission has monitored and enforced transposition of the Directive

23Following the Directive’s transposition deadline of 25 October 2013 and the Commission’s completeness checks of the transposition by the Member States, the Commission opened 26 infringement procedures for late or incomplete notification of transposition measures. In addition, the Commission initiated 21 infringement procedures on late or incomplete transposition of the Implementing Directive on the recognition of medical prescriptions issued in another Member State17. After all Member States provided complete notifications of transposition measures, the Commission closed these procedures by November 2017.

24The Commission checks Member States’ legislation to establish whether they had correctly transposed the Directive’s provisions. In order to target these checks, the Commission identified four priority areas that act as barriers to cross-border patients: reimbursement systems, the use of prior authorisation, administrative requirements and the charging of incoming patients. Following these checks, the Commission opened 11 own-initiative infringement cases, four of which had been closed by November 2018, after Member States amended national transposition measures.

25We consider that the Commission’s checks has led to improvements in the systems and practices employed by the Member States.

The Commission has reported on the operation of the Directive in a timely manner

26The Commission is required to draw up a report every three years, starting in 2015, on the operation of the Directive18. These reports should include information on patient flows and the costs associated with patients’ mobility. While the Directive does not oblige Member States to collect data on patients’ flows, it specifies that they shall provide the Commission with assistance and all available information for preparing the report. In 2013, Member States agreed to provide specific data to the Commission on an annual basis.

27The majority of Member States were late in the adoption of the national transposition measures (see paragraph 23) and this delayed their provision of data to the Commission in 2015. In 2017, 26 Member States provided it but for six of them, data was incomplete. In addition, data was not comparable from one country to another as some Member States reported all reimbursements without specifying whether they were granted under the Directive or the Regulation on the coordination of social security systems. The Commission recognised the limited accuracy of data included in the reports. For example, the overview of patient flows was incomplete. Table 1 shows that four Member States did not provide data on outgoing patient flows in 2016.

28Despite these challenges, the Commission met its reporting obligation on time. It adopted its recent report in September 2018 and presented an overview of patient flows and of the financial impact of cross-border healthcare under the Directive.

The Commission guided the National Contact Points in improving the information on cross-border healthcare

29The Commission supports and guides the National Contact Points with the aim of providing clear and comprehensive information on patients’ rights to cross-border healthcare. To do that the Commission published a number of relevant studies19. Prior to the Directive’s transposition deadline, in 2013 the Commission sent a guidance note to the Member States on cross-border healthcare treatment pathways available for patients: the Cross-border Healthcare Directive and the Regulation on the Coordination of Social Security systems.

30However, fewer than half of the National Contact Point websites explained the two different ways for patients to obtain healthcare in other countries20. In March 2018, the Commission sought to address the potential for confusion between the two pieces of legislation by holding a capacity-building workshop for NCPs and by developing a practical toolbox to help NCPs pass the information on to patients. Our survey showed that the competent authorities in the Member States welcomed the toolboxes, but that further work is needed to help explain the difference to patients.

31A recent Commission study21 considered that the information available to patients on NCPs websites was generally adequate and met the requirements of the Directive, but that the websites could provide more information on incoming patient rights and on the reimbursement of cross-border healthcare costs for outgoing patients. In addition, a report on the Directive by the European Parliament noted that “in-depth information on patients’ rights was generally lacking on the NCPs websites”22.

32NCPs are not required by the Directive to include information on European Reference Networks on their websites. We found that some NCPs did provide such information, and others were considering how to do so. German, Irish, Estonian, Lithuanian and UK representatives have already expressed interest in liaising with the ERN Board of Member States for ERNs23. The rare disease experts that we consulted considered that NCPs should provide such information about the Networks.

Exchanging patients’ health data across borders: high expectations had not been matched by results at the time of the audit

33Creating mechanisms to exchange patients’ health data within the EU requires a clear strategic and governance framework, supported by the Member States. Clear objectives should be set and performance monitored regularly. Before launching the large-scale projects, the Commission with the support of the Member States should estimate the volumes of potential users. Lessons should be learnt from the earlier pilot projects.

The 2018 eHealth Strategy did not include an implementation plan

34The Commission’s eHealth Action Plans set out its approach to eHealth, including to cross-border exchanges of patients’ health data. The current Action Plan runs from 2012 until 2020. In April 2018, the Commission adopted a new eHealth strategy24, which is broader in scope than the current Action Plan. It notably includes the possible expansion to cross-border exchange of electronic health records.

35In 2014, the Commission published an interim evaluation of the eHealth Action Plan25. While positive overall, the evaluation noted some weaknesses and recommended that the Commission should update the plan to include the most relevant issues, provide a clear governance structure and create a monitoring and coordination mechanism.

36The Commission implemented most of the actions foreseen in the eHealth Action Plan. It has not followed the 2014 evaluation recommendation to update its Action Plan nor revised it to reflect the 2018 eHealth Strategy. Therefore, the plan does not include relevant issues, such as the introduction of the General Data Protection Regulation. In addition, the Commission has not set out responsibilities for the plan’s implementation.

37The 2018 eHealth strategy refers to new challenges such as the introduction of the General Data Protection Regulation and cybersecurity threats. However, this strategy did not include an implementation plan with timelines for expected results and outputs that would show the Commission’s approach to implementing the eHealth strategy. When the Commission launched its 2018 strategy on eHealth the only evaluation of its 2012-2020 Action Plan dated from 2014.

The Commission underestimated the difficulties involved in deploying EU-wide eHealth Infrastructure

38The Commission has worked on exchanges of patient health data between Member States in two stages: a pilot project (epSOS)26 from 2008 to 2012, costing €18 million and an ongoing deployment project (EU-wide eHealth Infrastructure) with a budget of €35 million27 launched in 2015.

39epSOS’s goal was to develop an Information and Communication Technology framework and infrastructure to enable secure cross-border access to patient health information. The pilot was to test the functional, technical and legal feasibility and acceptance of the proposed solution for cross-border health data exchanges. It was intended to “demonstrate the practical implementation of the solution in a number of settings in a number of participating states”.

40The project developed the definitions of data content of Patient Summaries and ePrescriptions (see paragraph 09) as well as mechanisms for testing, reviewing and approving exchanges of health data across borders. It has contributed to the development of eHealth interoperability specifications and guidelines. It has also provided common standards to foster these exchanges and demonstrated Member States commitment to cooperation in this area.

41The project planning phase did not set the scope and scale of testing required before practical implementation. Testing of the feasibility of the proposed solution consisted of 43 transfers of patient data. This meant that the project provided a limited practical demonstration of the proposed solution. In the final review of the project, external evaluators concluded that the number of real Patient Summaries and ePrescriptions was “too low to consider the epSOS services as operational and robust”28. However, this exchange, while limited, was considered by the Commission a sufficient proof of concept for the eHDSI.

42The Commission assessed the epSOS project in 2014. This assessment noted that “although the expectations about statistically relevant numbers of patients’ encounters have not been met in the epSOS project so far, the concept of the epSOS approach for cross-border interoperability has been proven to be valid”29. In addition, interoperability problems at legal, organisational and semantic levels had proven to be a greater challenge than expected. The Commission also identified ineligible costs claims from the project’s contractors, mostly linked to personnel costs. At the time of our audit, the Commission was in the process of recovering ineligible expenses, amounting to 42 % of financing provided.

43Despite these challenges, in 2015 the Commission decided to use this pilot project’s outputs as the basis for the development of the large scale EU-wide eHealth Infrastructure (eHDSI). The eHDSI architecture, technical and semantical specifications, legal, organisational and policy agreements among the participating Member States are based on epSOS deliverables.

44We identified weaknesses in the Commission’s preparation for this complex project, notably insufficient estimation of the volumes of potential users (patients and providers, i.e. pharmacies and hospitals) of the cross-border eHealth services that eHDSI provides and an insufficient assessment of the cost-effectiveness of these services before launching the eHDSI. Therefore, we find that the Commission underestimated difficulties involved in deploying an EU-wide eHealth Infrastructure.

The Commission overestimated the likely take-up of the eHealth Digital Service Infrastructure

45Commission announcements on the likely level of health data exchanges across borders have been overoptimistic (see Box 3).

Box 3

The Commission’s announcements on the take-up of EU-wide eHealth Infrastructure

In December 2017 the Commission announced that: “In 2018, twelve EU Member States will start exchanging patient data on a regular basis”30.

On its website on eHealth Infrastructure governance, the Commission stated that “It is expected that towards 2019, the EU’s cross-border health data exchange starts to be an accepted practice of the national healthcare systems ...”31.

When assessing its own performance, the Commission reported in 2017, ten Member States as “having capacity to the health data exchange and join the Cross-Border eHealth Information Services”32. This figure was based on Member States’ self-reporting on a question about the establishment of their national eHealth portals and included Member States which had only started to build their portals, but had not confirmed their readiness to exchange health data across borders.

By the time of our audit (November 2018), exchanges of patients’ health data across borders had not yet started via the EU eHealth Infrastructure (see Annex II, which shows the planned ‘going-live’ deployment dates for cross-border health data exchanges in the Member States). By this time, the Commission had assessed the capacity of seven Member States33 to ‘go live’ in cross-border exchanges. Four of these Member States (Czechia, Estonia, Luxembourg and Finland) had undergone follow up checks. In October 2018, the eHMSEG recommended that they ‘go live’, provided that all corrective actions had been taken. Figure 4 presents the process by which Member States join the Cross-border eHealth Information Service and the 2018 state of play.

Figure 4

The process of joining the Cross-border eHealth Information Service – state of play 2018

Source: ECA based on information provided by the Commission.

We also found that these four Member States were admitted to the EU-wide eHealth Infrastructure to operate different types of eHealth services. At the time of the audit, Finland was ready to send ePrescriptions, while Estonia could receive them (in early 2019 this was the only exchange of ePrescription available in Europe). According to the Commission, 550 ePrescriptions were settled this way between January and the end of February 2019. Czechia and Luxembourg were ready to receive Electronic Patient Summaries from abroad, but no Member States could yet send them via eHDSI. In addition, at the start only some national Healthcare Providers and pharmacies in these countries will use the system. Box 4 explains how patients could benefit from cross-border exchanges of ePrescriptions and Electronic Patient Summaries.

Box 4

Cross-border exchanges

ePrescriptions (the case of Finland and Estonia),

When a patient with an ePrescription issued in Finland goes to an Estonian pharmacy to get their medicine, the pharmacy should register the patient’s ID. The pharmacy should then send the prescription data, provided patient consent is available, to the Estonian eHealth portal (NCPeH) which should forward it to the Finnish eHealth portal. After the medicine is dispensed to the patient by the Estonian pharmacy, the Finnish eHealth portal should be informed that the ePrescription has been processed (see Figure 1).

and Electronic Patient Summaries.

When an individual has a medical emergency or makes an unplanned visit to a healthcare provider abroad, medical personnel could electronically access basic medical information about the patient in the patient’s home country via the EU eHealth portal. The Patient Summary may include information on the patient’s allergies to medication and can facilitate patient’s diagnosis abroad.

European Reference Networks for rare diseases are an ambitious innovation but their sustainability has not been demonstrated

48For the Commission to effectively support the Member States in the development of the European Reference Networks, such support needs to be provided in the context of the legal framework, and with a coherent strategy and a clear roadmap.

The Commission has not updated its framework for EU actions on rare diseases

49The development of the European Reference Networks is part of the EU’s wider policy on rare diseases, which includes such elements as support for the development of national rare disease plans, improved standardisation of rare disease nomenclature and support for research on rare diseases. The Commission’s 2008 Communication on rare disease aimed to “encourage cooperation between the Member States and if necessary to lend support to their action”. The objective was to set out “an overall Community strategy for support to Member States”34 in tackling rare diseases. The Council endorsed this approach in its Recommendation on an action in the field of rare diseases of 8 June 200935.

50The Commission published an implementation report on both, the Communication and the Council Recommendation in 2014. The report concludes that “by and large, the objectives of the Communication and the Council Recommendation have been reached”. These objectives included the establishment of a clear definition of rare diseases or improvement of their codification in the healthcare systems. The report does caution that “there is still a long way to go” to ensure rare disease patients across the EU get the care they need and points to the lack of rare disease strategies in some Member States as an area requiring further work. It lists 11 actions envisaged by the Commission including continued support for the European platform for rare diseases and for the development of rare disease plans.

51Despite the conclusion that the objectives had been reached, 9 of the 11 envisaged actions are a continuation of existing initiatives. The Commission has not updated its rare disease strategy since 2008, although it is managing important initiatives such as the Networks and the EU wide platform for rare diseases registries.

The Commission did not apply all lessons learned from the European Reference Networks pilots

52The Commission funded ten pilot Reference Networks between 2007 and 2013. The Commission’s consultative committee on rare diseases (EUCERD)36 evaluated these pilot ERNs and published a “Preliminary analysis of the outcomes and experiences of pilot European Reference Networks for rare diseases” in 2011. However, when the Commission set up the ERNs, they tackled only some of the issues raised in the 2011 evaluation e.g. support for patient registries, the need for a dedicated Information and Communication Technology tool and for each Network member to have quality control processes for its care practices. Outstanding issues include:

- sustainability of the Networks beyond their initial funding period;

- the development of a continuous monitoring and quality control system for the Network members;

- the administrative challenges and financial costs of expanding a Network and

- sustainable support for patient registries.

The Board of Member States for the Networks has, since its launch in 2014, continued to work on these outstanding points. It has made progress on continuous monitoring and quality control (for which in September 2018 it approved a set of core indicators collected by the ERNs). However, new issues such as the integration of the Networks into national healthcare systems and collaboration with industry have emerged and have yet to be resolved. Figure 5 illustrates the different challenges facing the Networks, which the Commission, the Board of Member States or the Networks Coordinators Group are currently trying to address.

Figure 5

Challenges to the European Reference Networks development

Source: ECA, based on Board of Member States for European Reference Networks minutes.

The Commission supported the establishment of 24 European Reference Networks but did not create an effective system to assess participants

54The Directive mandated the Commission to establish specific criteria and conditions which Healthcare Providers must fulfil in order to join an ERN37. The Commission used a consultant to develop a set of guidelines for applicants as well as for the Independent Assessment Body (IAB), which evaluated the ERNs and individual Healthcare Provider applications. The Commission worked to raise awareness of the launch of the ERNs among relevant stakeholders and its initial objective to support the establishment of ten ERNs38 was exceeded as 24 were created (see Annex III showing a list of European Reference Networks).

55Figure 6 illustrates the assessment process of Healthcare Provider’s applications to join the ERNs. Before submitting an application, every Healthcare Provider had first to be endorsed by their Member State’s competent authority. The assessment procedure at the EU level was limited to an eligibility check of applications and the assessment of a sample of 20 % of individual applications.

Figure 6

Decision tree for the eligibility check and assessment process for Healthcare Provider (HCP) applications to join European Reference Networks

Source: ECA analysis based on documents provided by Consumer, Health, Agriculture and Food Executive Agency.

The Independent Assessment Body produced 62 negative preliminary reports. For all these cases, the applicants provided information39 on outstanding issues which enabled the Assessment Body to give a positive opinion. However, our examination of a sample40 of assessment reports found that in many cases, the Assessment Body awarded its final positive opinion on the basis of incomplete information. The final outcome of the assessment process was that 952 Healthcare Providers out of the 953 that applied were accepted into the ERNs. We conclude in practice that this assessment process added limited value to the establishment of the ERNs.

57The sample-based system of assessment was not originally complemented by any other monitoring or assessment measures. The Commission has been working with the Member States representatives and ERN coordinators since December 2016 on developing a system of continuous monitoring by the Commission and periodic self-evaluation for all ERNs members. However, at the time of the audit they had not decided what measures should be taken if this monitoring system identifies under-performing Healthcare Providers. The Commission also plans to evaluate the ERNs at the end of their five-year financing period41.

The EU budget does not contain a specific budget line for the European Reference Networks

58The Directive required the Commission to support Member States in the development of the ERNs. The EU budget does not contain a specific budget line for the ERN costs. To support the ERNs’ operations, the Commission has provided funding from different spending programmes (Health Programme, Connecting Europe Facility) and through different spending mechanisms (calls for proposals and tenders). The Commission did not set out a comprehensive spending plan for the period 2017-2021 and communicate it to the ERNs and budgetary authority.

59In November 2017, the Commission provided the Networks with the Clinical Patient Management System for sharing and consulting patients’ data (see paragraph 15). Patients’ consultations using this system is one of the significant aspects of the ERNs’ operations. However, the use of cross-border consultations through CPMS highlighted the issue of recognising doctors’ time spent on the diagnosis and treatment of patients in another Member State. Figure 7 shows the number of consultation panels created in the System per ERN between November 2017 and December 2018.

Figure 7

Consultation panels are a sign of ERN operation

Source: Commission’s CPMS report 12.2018

Each ERN coordinator currently receives €1 million over a period of five years in EU funding42 for administrative costs. There were often delays in the payment of the annual administrative funding to the ERNs. A Commission survey of ERN coordinators in January 2018, to which 20 ERNs responded, showed that sustainability of financing is one of the top two challenges facing the ERNs43. 17 of the 24 ERNs have included identification of other funding sources within their objectives or risk-mitigation strategies.

61In addition to this administrative funding the Commission provided grants to the ERNs to support the achievement of their objectives. It launched procurement procedures to develop activities to support the establishment and development of the Networks. By the end of 2018, these included:

- the use of the eHealth solutions, i.e. Clinical Patient Management System (€5 million allocated from the Connecting Europe Facility fund);

- the development of the Clinical Practice Guidelines (in total €4 million from the Health Programme);

- the ERNs’ registries (in total €2 million for five ERNs in 2018 from the Health Programme);

- the provision of training and tools for ERN coordinators (call for tender to external company with estimated value: €400 000);

- the provision of secretarial support to the ERN coordinators Working Group (call for tender to external company with estimated value: €380 000);

- the development of templates of the ERNs’ documents (call for tender to external company with estimated value: €100 000).

The ERN coordinators consider that participating in the numerous calls for proposals run by the Commission imposed significant administrative burden. Moreover, the long-term sustainability of the ERNs’ registries, currently financed with Health Programme funds, is unclear despite the Commission emphasising the risk of project based funding for registries in its 2008 Communication on rare diseases.

Despite delays, the Commission is now launching an EU wide platform for rare disease registries

63In its 2008 Communication on rare diseases, the Commission highlighted the importance of databases and registries to enable epidemiological and clinical research on rare diseases. It further stressed the importance of ensuring the long-term sustainability of these systems. In response to this challenge, in 2013, DG JRC started to develop the European Platform for Rare Diseases Registries co-funded by the Health Programme44 and open to all European rare disease registries. The JRC’s platform aims to deal with the fragmentation of data contained in rare disease patient registries across Europe by promoting EU-level standards for data collection and providing interoperability tools for rare disease data exchanges.

64We found that, in parallel to the JRC platform, the Commission funded another project, RD-Connect from research and innovation funding programme (Seventh Framework Programme), which had as one of its objectives the creation of a directory of patient registries for rare disease research. Both projects have a similar aim of connecting registries in the EU to make it easier for researchers to access data on rare diseases. As a result, the Commission is funding two projects with potentially overlapping outputs.

65At the time of the audit the JRC platform was due to go live in February 2019, more than two years later than initially planned. One of the reasons for the delay was that, the development of the JRC platform also included transferring two existing networks45 to the JRC, which required more time and resources than anticipated. We found that the original timing and budget allocation planned for the platform were unrealistic. Furthermore, DG SANTE’s funding provided to the JRC platform currently covers approximately 45 % of the costs of the work but there is no provision for the financial sustainability of the platform or planning to ensure that the platform is successful other than a dissemination plan drafted in the fourth quarter of 2017.

Conclusions and recommendations

66We examined the Commission’s oversight of the transposition of the Cross-border Healthcare Directive in the Member States and the results achieved so far for cross-border exchanges of health data. We also assessed EU actions in the field of rare disease policy. We sought to answer the following question:

Do EU actions in cross-border healthcare deliver benefits for patients?

67We conclude that while EU actions in cross-border healthcare were ambitious and enhanced Member States collaboration, they require better management. The impact on patients was limited at the time of our audit.

68We found that the Commission oversaw the implementation of the Directive in the Member States well (paragraphs 23 to 28), and supported the work of National Contact Points responsible for providing information for cross-border patients. It has recently developed a practical toolbox for the NCPs. However, EU patients still face challenges in accessing healthcare abroad and only a minority of potential patients are aware about their rights to seek cross border healthcare. The complexity of cross-border healthcare treatment pathways available for patients under the Cross-border Healthcare Directive and Social Security Coordination Regulation makes it difficult to provide patients with clear information. NCPs give limited information about ERNs on their websites (paragraphs 29 to 32).

Recommendation 1 – Provide more support for National Contact PointsThe Commission should:

- building on former actions, support the work of National Contact Points, including on how best to communicate the relationship between the Cross-border Healthcare Directive and the Social Security Coordination Regulation pathways,

- provide guidance on presenting information about European Reference Networks on the National Contact Points websites;

- follow up on the use by National Contact Points of the 2018 toolbox.

Target implementation date: 2020

69In 2018, the Commission adopted a new eHealth strategy without updating the current eHealth Action Plan. The 2018 eHealth strategy does not include an implementation plan committing to timelines for expected results and outputs (paragraphs 34 to 37).

70The work on cross-border exchanges of health data has resulted in the creation of interoperability standards. The Commission, in cooperation with the Member States, is building EU-wide infrastructure for these exchanges. The Commission did not estimate the likely numbers of users of the EU-wide eHealth Infrastructure before launching the project. The Commission’s forecasts of the likely take-up of cross-border exchanges of health data were overoptimistic. There were delays in the deployment of the eHealth Infrastructure and cross-border health data exchanges via eHealth Infrastructure had not started at the time of our audit (paragraphs 38 to 47).

Recommendation 2 – Better prepare for cross border exchanges of health dataThe Commission should:

- assess the results achieved for cross-border exchanges of health data via EU-wide eHealth Infrastructure (for ePrescriptions and Electronic Patients Summaries);

- in the light of this, assess the 2012 eHealth Action Plan and the implementation of the 2018 eHealth strategy, including whether these actions have provided cost-effective and timely solutions, and meaningful input to national healthcare systems.

Target implementation date: 2021

Target implementation date: 2021

The launch of the European Reference Networks is an ambitious innovation in cross-border healthcare cooperation, particularly as healthcare is a Member State competence. The Commission provided the ERNs set up with the Clinical Patient Management System to facilitate sharing of patient data. The ERNs were established in March 2017 and it is too early to assess their success in adding value to Member States efforts to provide better care to rare disease patients.

72We found that the Commission has not taken stock of its progress in the implementation of the EU rare disease strategy since 2014 (paragraphs 49 to 51). The process of establishing the ERNs and the Commission’s on-going support for them was marked by shortcomings and the Commission did not set out a spending plan for the ERNs. The ERNs face significant challenges to ensure they are financially sustainable and are able to operate effectively within and across national healthcare systems. The Commission has therefore encouraged Member States to integrate ERNs into national healthcare systems (paragraphs 52 to 62). We also found that there were delays in launching the EU wide platform for rare disease registries (paragraphs 63 to 65).

Recommendation 3 – Improve support to facilitate rare disease patients’ access to healthcareThe Commission should:

- assess the results of the rare disease strategy (including the role of the European Reference Networks) and decide whether this strategy needs to be updated, adapted or replaced;

- in consultation with the Member States set out ways forward to address the challenges faced by the European Reference Networks (including integration of the European Reference Networks into national healthcare systems, and patients’ registries);

- work towards a simpler structure for any future EU funding to the European Reference Networks and reduce their administrative burden.

Target implementation date: 2023

Target implementation date: 2020

Target implementation date: 2022

This Report was adopted by Chamber I, headed by Mr. Nikolaos MILIONIS, Member of the Court of Auditors, in Luxembourg at its meeting of 10 April 2019.

For the Court of Auditors

Klaus-Heiner LEHNE

President

Annexes

Annex I – Comparison of patients’ rights to cross-border healthcare under the Directive and the Regulation

| DIRECTIVE | REGULATION | |

|---|---|---|

| Sector | Public + Private | Public only |

| Eligible treatments | Treatments available under patients’ own country's health-insurance | Treatments available under the other country's national health-insurance |

| Prior authorisation | Required under certain circumstances | Always required for planned care Not required for emergency situations |

| Costs covered | Reimbursement up to the amount had the treatment been carried out in patients’ home country | Complete funding (barring co-payment charges) |

| Reimbursement of co-payment charges | Up to the limit of the cost in the home country | Yes (under certain conditions) |

| Method of payment | Patients pay up-front and are reimbursed at a later time (reimbursement-system) | Between countries, no up-front payment from patients required (funding-system) |

| Eligible countries | All EU & EEA countries | All EU & EEA countries + Switzerland |

Source: ECA based on the website ‘Healthcare beyond borders’.

Annex II – State of play of planned deployment for cross-border health data exchanges in the EU

Source: ‘Service Catalogue, Delivery and Overall Deployment – eHDSI – ePrescription and Patient Summary’ available on eHDSI website46.

Annex III – List of European Reference Networks

| ERN abbreviated name | ERN full name |

|---|---|

| Endo-ERN | ERN on endocrine conditions |

| ERKNet | ERN on kidney diseases |

| ERN BOND | ERN on rare bone disorders |

| ERN CRANIO | ERN on craniofacial anomalies and ENT disorders |

| EpiCARE | ERN on rare and complex epilepsies |

| ERN EURACAN | ERN on rare adult solid cancers |

| EuroBloodNet | ERN on rare haematological diseases |

| ERN eUROGEN | ERN on urogenital diseases and conditions |

| ERN EURO-NMD | ERN on neuromuscular diseases |

| ERN EYE | ERN on eye diseases |

| ERN Genturis | ERN on genetic tumour risk syndromes |

| ERN GUARD-Heart | ERN on rare and low prevalence complex diseases of the heart |

| ERN ERNICA | ERN on inherited and congenital abnormalities |

| ERN ITHACA | ERN on congenital malformations and rare intellectual disability |

| ERN LUNG | ERN on respiratory diseases |

| ERN TRANSPLANT-CHILD | ERN on transplantation in children |

| ERN PaedCan | ERN on paediatric cancer (haemato-oncology) |

| ERN RARE-LIVER | ERN on hepatological diseases |

| ERN ReCONNET | ERN on connective tissue and musculoskeletal diseases |

| ERN RITA | ERN on immunodeficiency, autoinflammatory and autoimmune diseases |

| ERN-RND | ERN on neurological diseases |

| ERN Skin | ERN on rare skin disorders |

| MetabERN | ERN on hereditary metabolic disorders |

| VASCERN | ERN on multisystemic vascular diseases |

Acronyms and abbreviations

AAR: Annual Activity Report

CEF: Connecting Europe Facility

CPMS: Clinical Patient Management System

DG SANTE: Directorate-General for Health and Food Safety

eHDSI: eHealth Digital Service Infrastructure

eHMSEG: eHDSI Member States Expert Group

epSOS: Smart Open Service for European Patients

ERN: European Reference Network

EUCERD: European Union Committee of Experts on Rare Diseases

HCP: Healthcare Provider

IAB: Independent Assessment Body

JRC: European Commission’s Directorate-General Joint Research Centre

NCP: National Contact Point

NCPeH: National Contact Point for eHealth

RD: Rare Disease

TFEU: Treaty on the Functioning of the EU

Glossary

Cross-border healthcare: healthcare provided or prescribed outside the insured person's country of affiliation

eHealth: use of Information and Communication Technology in health products, services and processes combined with organisational change in healthcare systems and new skills. eHealth is the transfer of healthcare by electronic means

Electronic Health Record (EHR): a comprehensive medical record or similar documentation of the past and present physical and mental state of health of an individual in electronic form, and providing for ready availability of these data for medical treatment and other closely related purposes

ePrescription: a prescription for medicines or treatments, provided in electronic format with the use of software by a legally authorised health professional and the electronic transmission of prescription data to a pharmacy where the medicine can then be dispensed

European Reference Networks (ERNs): virtual networks involving healthcare providers across Europe. They aim to tackle complex or rare diseases and conditions that require highly specialised treatment and a concentration of knowledge and resources

ERN Coordinator: for each network, one member acts as coordinator. They facilitate cooperation between network’s members.

Interoperability: capacity to make use of and exchange data between different health systems in order to interconnect information

Rare Disease (RD): a disease or disorder is defined as rare in the EU when it affects fewer than 5 in 10 000 people

Endnotes

1 Directive 2011/24/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 9 March 2011 on the application of patients’ rights in cross-border healthcare (OJ L 88, 4.4.2011, p. 45).

2 Article 168 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU (TFEU).

3 Regulation (EC) No 883/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004 on the coordination of social security systems (OJ L 166, 30.4.2004, p. 1). This Regulation is of relevance to cross-border healthcare in the context of labour mobility and tourism and their links between healthcare and social security systems.

4 According to results by the survey of NCPs carried out by the Cross-border Healthcare Expert Group in May 2017 and confirmed by the ECA’s own survey of Cross-border Healthcare Expert Group members.

5 Commission report on the operation of Directive 2011/24/EU on the application of patient rights in cross-border healthcare,

6 Annex B of Commission report on the operation of Directive 2011/24/EU, COM(2018) 651 final.

7 European Territorial Cooperation (ETC), better known as Interreg, is one of the two goals of the EU cohesion policy and provides a framework for joint actions and policy exchanges between national, regional and local stakeholders from different Member States.

8 Study on Cross-Border Cooperation. Capitalising on existing initiatives for cooperation in cross-border regions – Commission study published in March 2018. The list of projects and their objectives as identified by the study may be accessed online here.

9 Commission’s Communication on enabling the digital transformation of health and care in the Digital Single Market; empowering citizens and building a healthier society of 25 April 2018, COM(2018) 233 final. The Communication resulted from the mid-term review of the Digital Single Market Strategy.

10 Belgium, Czechia, Germany, Estonia, Ireland, Greece, Spain, France, Croatia, Italy, Cyprus, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Hungary, Malta, the Netherlands, Austria, Poland, Portugal, Slovenia, Finland, and Sweden.

11 Ten Member States reported more that 90 % as national coverage for ePrescriptions in 2017 (Croatia, Czechia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Greece, Italy, Portugal, Spain and Sweden).

12 epSOS – Smart Open Service for European Patients – project funded under the Competitiveness and Innovation Programme (CIP) theme 3: Sustainable and interoperable health services.

13 Council Recommendation of 8 June 2009 on an action in the field of rare diseases.

14 The Board of Member States for ERNs was created by the Commission Implementing Decision 2014/287/EU of 10 March 2014 setting out criteria for establishing and evaluating European Reference Networks and their Members and for facilitating the exchange of information and expertise on establishing and evaluating such Networks (OJ L 147, 17.5.2014, p. 79).

16 Denmark, Italy, Lithuania, the Netherlands and Sweden.

17 Commission Implementing Directive 2012/52/EU of 20 December 2012 laying down measures to facilitate the recognition of medical prescriptions issued in another Member State (OJ L 356, 22.12.2012, p. 68).

18 Article 20 of the Directive.

19 These studies include: 2012 Study on a best practice based approach to National Contact Point websites with recommendations to Member States and the Commission on how to provide the appropriate information on various essential aspects of cross-border healthcare through NCPs; 2014 Study on the impact of information on patients’ choice within the context of the Directive; 2015 Evaluative study on the operation of the Directive containing inter alia a review of NCP websites.

20 According to a survey of NCPs carried out by the Commission for its Report on the operation of the Directive.

21 Study on cross-border health services: enhancing information provision to patients published on 20 July 2018.

22 The report on the implementation of the Cross-Border Healthcare Directive of 29 January 2019 by the Committee on the Environment, Public Health and Food Safety.

23 The report from the meeting of NCPs of 5 May 2017.

24 Commission’s Communication on enabling the digital transformation of health and care in the Digital Single Market; empowering citizens and building a healthier society of 25 April 2018, COM(2018) 233 final. The Communication resulted from the mid-term review of the Digital Single Market Strategy.

25 Interim evaluation of the eHealth Action Plan 2012-2020, Deloitte study prepared for the Commission.

26 The total project budget was €38 million of which the EU agreed to co-finance €18 million. In total 24 countries participated in the project.

27 The amount includes IT services for the ERNs.

28 Final technical review report of EpSOS of 12 November 2014

29 In 2014, DG SANTE’s Information Systems Unit carried out an epSOS project assessment in order to obtain an overview of what the project delivered in terms of output and achievements and to summarise the conclusions about the maturity of the project for potential further large-scale implementation.

30 Commission’s website: Cross-border digital prescription and patient data exchange are taking off.

31 Commission’s website: eHDSI governance.

32 Annex of the 2016 Annual Activity Report (AAR) – Health and Food Safety. In its 2017 AAR, the Commission reported nine Member States, as Denmark withdrew from the Cross-Border eHealth Information Services (see paragraph 10 and Box 1).

33 Czechia, Estonia, Croatia, Luxembourg, Malta, Portugal, and Finland.

34 Commission Communication “on Rare Diseases: Europe’s challenge”, COM(2008) 679 final.

35 Council Recommendation of 8 June 2009 on an action in the field of rare diseases.

36 European Union Committee of Experts on Rare Diseases (EUCERD) set up by the European Commission Decision of 30 November 2009 (2009/872/EC).

37 The Commission developed the framework for this work in the Implementing and delegated decisions of 10 March 2014.

38 DG SANTE 2016 AAR (Annex A, p. 169) indicates an interim milestone of ten ERNs under the result indicator 1.5.A: number of established ERNs.

39 Article 4(5) of Commission Implementing Decision 2014/287/EU.

40 In our sample of 50 Healthcare Providers assessment reports from 23 ERNs, we found that 30 Healthcare Providers did not provide information on clear action plan.

41 Article 14 of Commission Implementing Decision 2014/287/EU of 10 March 2014.

42 3rd Health Programme.

43 Board of Member States for ERNs, 6 March 2018.

44 Based on the Administrative Agreement between DG SANTE and the JRC.

45 The EUROCAT (European Surveillance of Congenital Anomalies) and SCPE (Surveillance of Cerebral Palsy in Europe).

46 In November 2018, the eHealth Network granted permission to ‘go live’ in the cross-border exchanges of health data via eHDSI to four Member States: Finland can send ePrescriptions, while Estonia can receive them. Czechia and Luxembourg are now allowed to receive Electronic Patient Summaries from abroad, but no Member States can yet send them via eHDSI. Three Member States (Croatia, Malta and Portugal) plan to apply to ‘go live’ in the first quarter of 2019.

47 Each Member State participating in the eHDSI received the funding from the CEF Telecom Programme to set up their National Contact Point for eHealth and start the cross border exchange of health data. The timeline of national implementation is part of a Grant Agreement signed by each Member State with the Commission.

48 The four countries authorised to go-live by the eHealth Network in November 2018 plan to deploy more than one service (sending and receiving e-prescriptions are two different services). (i) Finland has started sending e-prescriptions and plans to start receiving them by the end of 2019. (ii) Estonia has started receiving e-prescriptions and plans to start sending them by the end of 2019. (iii) The Czech Republic is ready to both send and receive patient summaries and plans to start sending and receiving e-prescriptions by the end of 2020. (iv) Luxembourg is ready to receive patient summaries and plans to start sending them by the end of 2019. It also plans to start sending e-prescriptions by the end of 2020.

On 11 March, Croatia received a positive recommendation by the eHealth Member State Expert Group (eHMSEG) to go live with the exchange of e-prescritions (both sending and receiving) and patient summaries (receiving), once the auditors confirmed that the last pending corrective action has been successfully implemented. This recommendation has to be adopted by the eHealth Network in order to become effective.

49 http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:12012E/TXT&from=EN

50 Notably: 1) The conclusions of the Rare 2030 Pilot Project funded by the European Parliament aims to support future policy decisions, examine the feasibility of new approaches and propose policy recommendations (results expected by early 2021); 2) the evaluation of the Third Health Programme (expected by mid-2021); 3) the evaluation of Directive 2011/24/EU on the application of patients’ rights in cross-border healthcare (expected by the end of 2022); 4) the evaluation of the Horizon 2020 Framework Programme for Research and Innovation (expected date still to be confirmed).

51 https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/cross_border_care/docs/2018_crossborder_frep_en.pdf

Audit team

This ECA’s special reports set out the results of its audits of EU policies and programmes, or of management-related topics from specific budgetary areas. The ECA selects and designs these audit tasks to achieve maximum impact by considering the risks to performance or compliance, the level of income or spending involved, forthcoming developments and political and public interest.

This performance audit was carried out by Audit Chamber I Sustainable use of natural resources, headed by ECA Member Nikolaos Milionis. The audit was led by ECA Member Janusz Wojciechowski, supported by Kinga Wiśniewska-Danek, Head of Private Office and Katarzyna Radecka-Moroz, Private Office Attaché; Colm Friel, Principal Manager; Joanna Kokot, Head of Task; Nicholas Edwards, Deputy Head of Task and Frédéric Soblet, Aris Konstantinidis, Anna Zalega, Michela Lanzutti, Jolanta Zemailaite, Auditors. Mark Smith provided linguistic support.

From left to right: Frédéric Soblet, Kinga Wiśniewska-Danek, Aris Konstantinidis, Janusz Wojciechowski, Colm Friel, Joanna Kokot, Nicholas Edwards, Jolanta Zemailaite.

Contact

EUROPEAN COURT OF AUDITORS

12, rue Alcide De Gasperi

1615 Luxembourg

LUXEMBOURG

Tel. +352 4398-1

Enquiries: eca.europa.eu/en/Pages/ContactForm.aspx

Website: eca.europa.eu

Twitter: @EUAuditors

More information on the European Union is available on the internet (http://europa.eu).

Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2019

| ISBN 978-92-847-1934-1 | ISSN 1977-5679 | doi:10.2865/280048 | QJ-AB-19-005-EN-N | |

| HTML | ISBN 978-92-847-1903-7 | ISSN 1977-5679 | doi:10.2865/946816 | QJ-AB-19-005-EN-Q |

© European Union, 2019.

For any use or reproduction of photos or other material that is not under the European Union copyright, permission must be sought directly from the copyright holders.

GETTING IN TOUCH WITH THE EU

In person

All over the European Union there are hundreds of Europe Direct Information Centres. You can find the address of the centre nearest you at: https://europa.eu/european-union/contact_en

On the phone or by e-mail

Europe Direct is a service that answers your questions about the European Union. You can contact this service

- by freephone: 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (certain operators may charge for these calls),

- at the following standard number: +32 22999696 or

- by electronic mail via: https://europa.eu/european-union/contact_en

FINDING INFORMATION ABOUT THE EU

Online

Information about the European Union in all the official languages of the EU is available on the Europa website at: https://europa.eu/european-union/index_en

EU Publications

You can download or order free and priced EU publications from EU Bookshop at: https://op.europa.eu/en/web/general-publications/publications. Multiple copies of free publications may be obtained by contacting Europe Direct or your local information centre (see https://europa.eu/european-union/contact_en)

EU law and related documents

For access to legal information from the EU, including all EU law since 1951 in all the official language versions, go to EUR-Lex at: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/homepage.html?locale=en

Open data from the EU

The EU Open Data Portal (http://data.europa.eu/euodp/en/data) provides access to datasets from the EU. Data can be downloaded and reused for free, both for commercial and non-commercial purposes.

Special Report

Special Report