A single European rail traffic management system: will the political choice ever become reality?

About the report: We assessed whether the European Rail Traffic Management System (ERTMS) has been properly planned, deployed and managed. ERTMS is designed to replace the diverse railway signaling systems around Europe with a single system that enables trains to travel uninterrupted across different countries and facilitates rail competitiveness. We found that deployment so far is at a low level and represents a patchwork, despite the fact that the ERTMS concept to enhance interoperability is not generally questioned by the rail sector. Infrastructure managers and railway undertakings are reluctant to invest due to the expenses entailed and the lack of an individual business case (for example in the Member States with well performing national systems and significant remaining lifetime). EU funding can only cover a limited amount of the investments. We make a number of recommendations to the European Commission, the Member States and the European Union Agency for Railways to help improve the deployment and financing of the system.

Executive summary

About ERTMS

ITo run trains on a rail network, a signalling system is needed to manage traffic safely and keep trains clear of each other at all times. However, each European country has developed its own technical specifications for such signalling systems, gauge width, safety and electricity standards. There are now around 30 different signalling systems across the EU managing railway traffic, which are not interoperable.

IITo overcome this and to help create a single European railway area, the European rail industry started developing a European control-command, signalling and communication system - ERTMS in the late 1980s/early 1990s and the European Commission supported its establishment as the single system in Europe. ERTMS’ objective is to replace all existing signalling systems in Europe with a single system to foster interoperability of national rail networks and cross-border rail transport. ERTMS is intended to guarantee a common standard that enables trains to travel uninterrupted across different countries and facilitate rail competitiveness.

IIITo help the Member States deploy ERTMS, approximately 1.2 billion euro was allocated from the EU budget between 2007 and 2013. 645 million euro came from the Trans-European Network for Transport Programme (TEN-T) and 570 million euro from the European Regional Development Fund and the Cohesion Fund. During 2014-2020, the estimated total is 2.7 billion euro, 850 million euro from the Connecting Europe Facility, which has replaced the TEN-T programme, and approximately 1.9 billion euro from the European Structural and Investments Funds.

How we conducted our audit

IVTo assess whether ERTMS has been properly planned, deployed and managed, and whether there was an individual business case, we examined:

- whether ERTMS had been timely and effectively deployed based on proper planning and cost estimates;

- whether there was a business case for individual infrastructure managers and railway undertakings;

- whether EU funding had been effectively managed to contribute to ERTMS deployment.

We visited six Member States: Denmark, Germany, Spain, Italy, the Netherlands and Poland. Altogether these Member States cover partly all nine core network corridors where ERTMS has to be fully deployed by 2030. The audit also covered the role played by the Commission in the planning, management, deployment and financing of ERTMS.

What we found

VISo far, deployment in the EU is at a low level and represents a patchwork, despite the fact that the ERTMS concept and vision to enhance interoperability is not generally questioned by the rail sector. The current low status of ERTMS deployment may mainly be explained by the reluctance of many infrastructure managers and railway undertakings to invest in ERTMS equipment due to the expense entailed and the lack of an individual business case for many of them. EU funding, even if better managed and targeted, can only cover a limited amount of the overall cost of deployment.

VIIThis puts not only the achievement of the deployment targets set for 2030 and investments made so far at risk, but also the realization of a single railway area as one of the major Commission’s policy objectives. It may also adversely affect the competitiveness of rail transport as compared with road haulage.

VIIIDespite the strategic political decision to deploy a single signalling system in the whole EU, no overall cost estimate was performed to establish the necessary funding and its sources. The legal obligations introduced did not imply the decommissioning of national systems, nor are they always aligned with the deadlines and priorities included in EU transport policy. As of today, the level of ERTMS deployment across the EU is low.

IXERTMS is a single system for multiple infrastructure managers and railway undertakings with diverse needs. However, it entails costly investments with no immediate benefit in general for those who have to bear the cost. Problems with compatibility of the different versions installed as well as the lengthy certification procedures also adversely affect the individual business case for infrastructure managers and railway undertakings. Despite the new European Deployment Plan, major challenges of successful deployment remain.

XEU financial support is available for ERTMS investments both trackside and on-board, but it can only cover a limited amount of the overall cost of deployment. It leaves most of the investment to individual infrastructure managers and railway undertakings which do not always benefit, at least immediately, from the deployment of ERTMS. In addition, not all EU funding available for ERTMS was finally allocated to ERTMS projects and it was not always well targeted.

What we recommend

XIThe Court makes a number of recommendations concerning: the assessment of ERTMS deployment costs; decommissioning of national signalling systems; individual business case for infrastructure managers and railway undertakings; compatibility and stability of the system; role and resources of ERA; alignment of national deployment plans, monitoring and enforcement; absorption of EU funds for ERTMS projects and better targeting of EU funding.

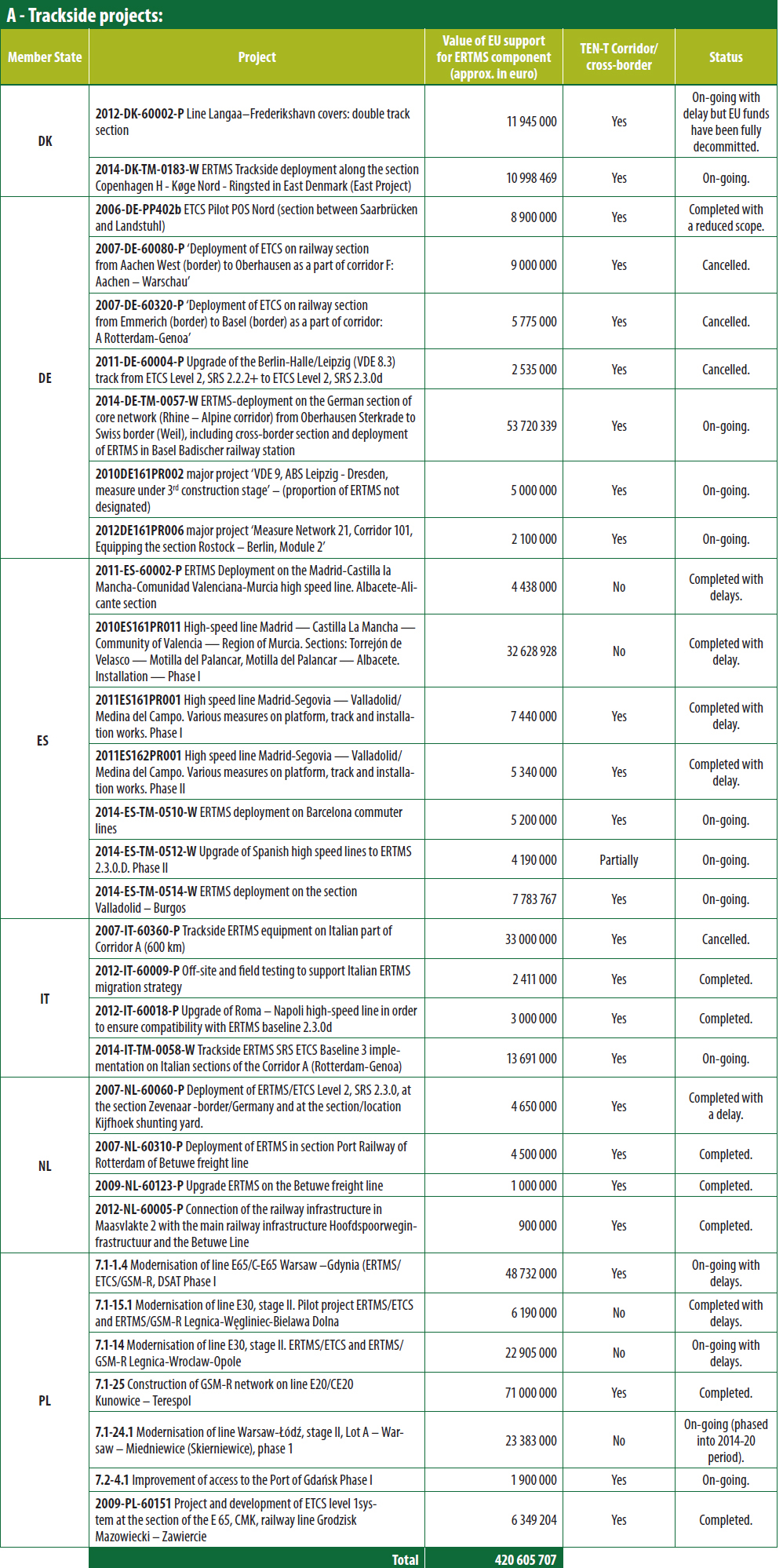

Introduction

Background

01The mobility of goods and persons is an essential component of the EU internal market and the competitiveness of European industry and services, and has a significant impact on economic growth. Rail is considered to be one of the most environmentally friendly modes of transport and has been promoted by the EU as one of the pillars of European transport policy over the last decades.

02To run trains on a rail network, it is necessary to have a rail signalling system so that railway traffic can be managed safely and trains kept clear of each other at all times. These systems usually consist of equipment placed both on the tracks and on the locomotives or entire trainsets.

03Over time, each European country has developed its own technical specifications for its signalling system, gauge width, safety and electricity standards. This represents a significant barrier to trans-European interoperability and results in additional costs and technical constraints. In particular, there are around 30 train signalling systems across the European Union, which are not interoperable (see Annex I). As a result, locomotives or trainsets running in several countries or even within a single country need to be equipped with different and multiple national signalling systems.

04In our previous report on rail freight transport1, we already highlighted the fact that among other operational obstacles the different signalling systems in place in the European Union rail network hinder interoperability. We also noted that the European Rail Traffic Management System (ERTMS) was being implemented slowly. Furthermore, we reported on the problems related to implementing projects on cross-border sections in two other our reports published in 20052 and 20103.

What is ERTMS?

05In the late 1980s/early 1990s, in order to overcome this situation caused by different national signalling systems and contribute towards the creation of a single European railway area, the European rail industry started developing a European control-command, signalling and communication system – ERTMS, and the Commission supported its establishment as the single system in Europe. The ultimate objective of this was to replace all the existing signalling systems in Europe with a single system designed to foster interoperability among national rail networks and cross-border rail transport. ERTMS is intended to guarantee a common standard that enables trains to travel uninterrupted across different countries thereby facilitating rail competitiveness.

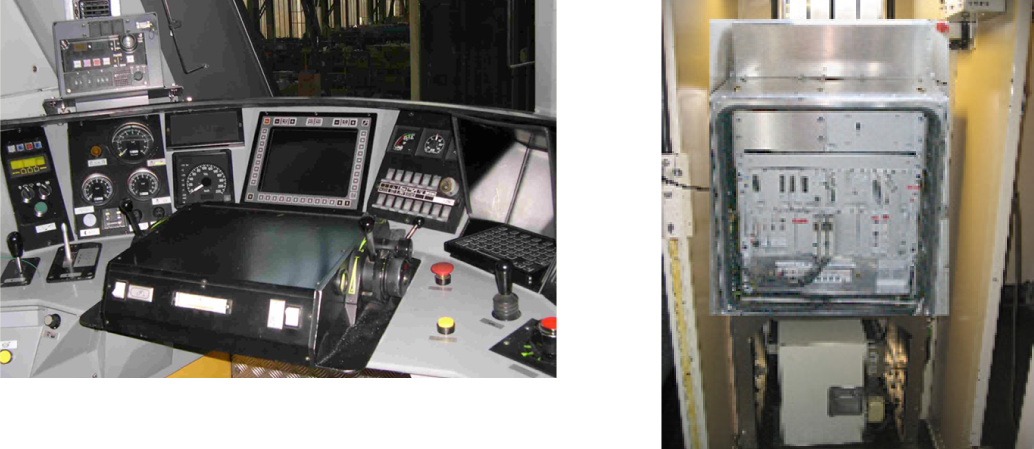

06ERTMS is composed of two software-based sub-systems: trackside and on-board, and both the infrastructure and the train must be equipped4 for the system to work. The trackside system and the system installed on the vehicles exchange information (see Figure 1 and Box 1) enabling continuous supervision of the maximum speed allowed for operation and gives the driver all the information needed to operate with cab signalling. Detail description of the ERTMS system is outlined in Annex II.

Figure 1

ERTMS functioning (level 1 and 2)

Source: European Court of Auditors.

Box 1

ERTMS track side and on-board components

Trackside: A Eurobalise is a passive device that lies on the track, storing data related to the infrastructure, such as speed limits, position references and gradients.

On-board: Driver Machine Interface, which is the interface between the driver and ERTMS, and Euro Vital Computer – a unit with which all the other train functions interact.

©Société nationale des chemins de fer luxembourgeois - CFL.

The successful deployment of ERTMS depends on various stakeholders. While the Commission is responsible for the policy, which it executes together with the European Coordinator and the European Union Agency for Railways (ERA), the product itself is delivered by the rail manufacturing industry according to procurement specifications and contractual requirements. Before being put into operation all the equipment must be tested and certified by notified bodies and authorised by national safety authorities or ERA.

08Physical deployment requires both infrastructure managers and railway undertakings to invest in ERTMS. Infrastructure managers, usually operating under the umbrella of the ministry responsible for transport and infrastructure in each Member State, have to deploy ERTMS trackside infrastructure. Railway undertakings (including fleet owners), which after the rail market liberalisation in the EU may be both public and private companies, have to invest in ERTMS on-board.

The history of ERTMS

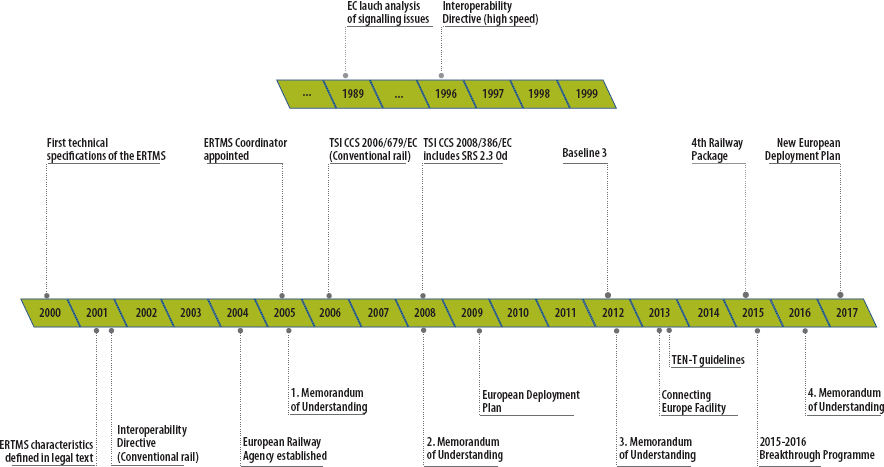

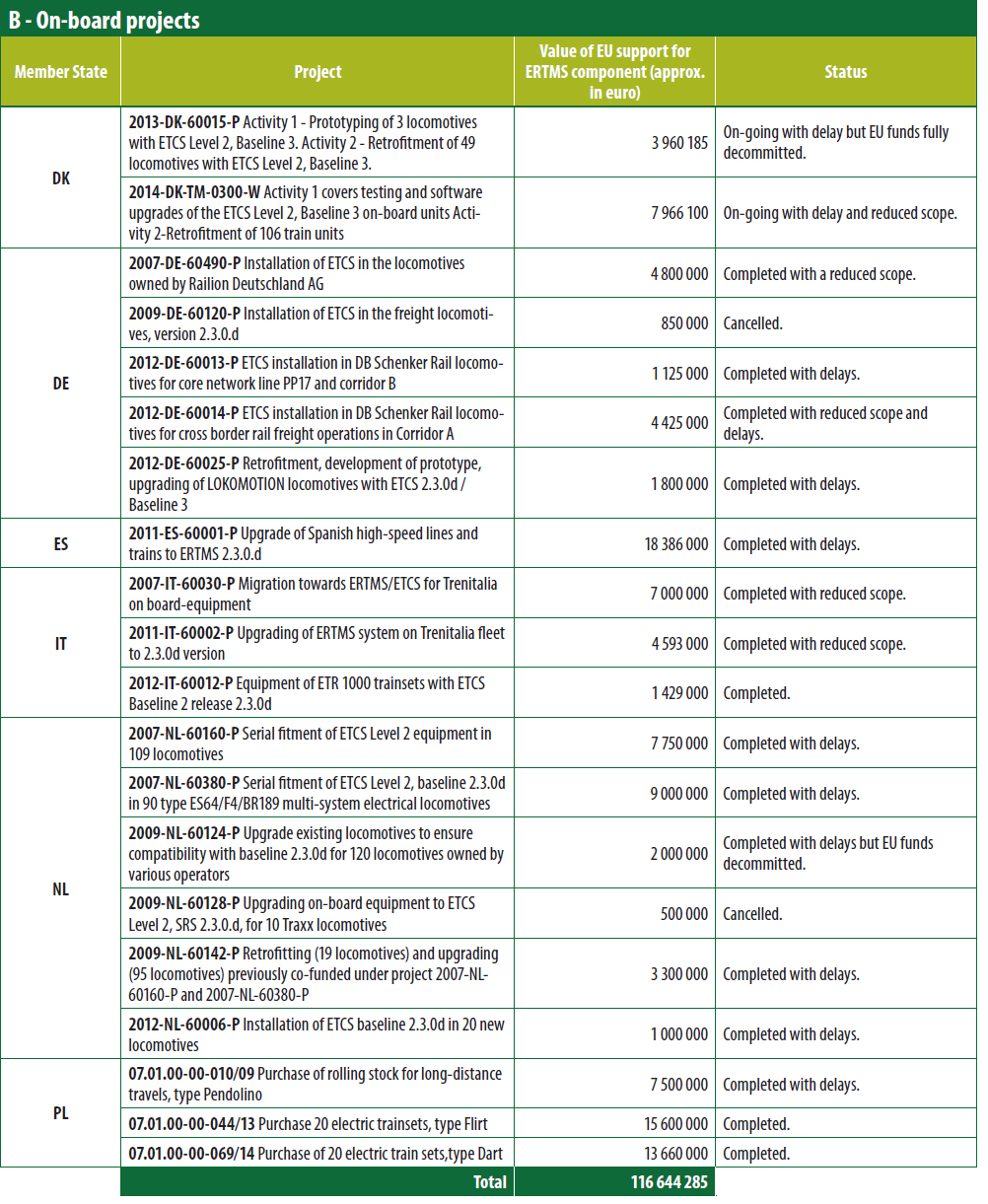

09The concept of a single EU signalling system to enhance interoperability dates back to 1989, when the rail industry and the Commission launched an analysis of rail signalling issues across the EU Member States, and, since then, it has constantly evolved, as summarised in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Timeline of ERTMS history

Source: European Court of Auditors.

The first legislative acts serving this objective were issued in 1996, with the ‘interoperability directive’ on a high-speed rail system5 and in 2001, with the interoperability directive on the trans-European conventional rail system6. In 2004 the European Railway Agency (ERA)7 was established with the objective of developing the technical specifications for interoperability (‘TSIs’). In July 2005, a European ERTMS Coordinator was appointed8. Between 2005 and 2016 the Commission (and ERA since 2008) signed four Memoranda of Understanding with the rail stakeholders, aiming at strengthening cooperation and speeding up ERTMS deployment.

11In 2009, based on the information provided by the Member States9, the Commission adopted an ERTMS European Deployment Plan (EDP)10. This decision set out the detailed rules for ERTMS deployment and identified six ERTMS corridors and a number of main European ports, marshalling yards, freight terminals and freight transport areas to be covered by ERTMS connections, together with their respective timetables, between 2015 and 2020.

12Another important step was the adoption of the TEN-T guidelines in December 201311. These guidelines stated that the trans-European transport network should be developed through a dual-layer structure consisting of a comprehensive network (123 000 km), which includes a core network (66 700 km), comprising in itself nine core network corridors (51 000 km, which had been aligned with the ERTMS corridors included in the European Deployment Plan). These guidelines envisaged that the core network and the comprehensive network should be equipped with ERTMS by 2030 and 2050 respectively. Figure 3 shows the nine core network corridors.

Figure 3

Map of the nine core network corridors

Source: European Commission.

On 30 January 2013, the Commission adopted its proposal for the Fourth Railway Package to complete the single European railway area. The technical pillar which entered into force in June 2016 covers elements directly linked to ERTMS such as rail governance issues and the reinforcement of the role of the ERA, which will become the system authority for ERTMS12 as from mid-2019. Finally, in January 2017, a new ERTMS European Deployment Plan13 was adopted (see also paragraph 63 and 67).

EU financial support for ERTMS

14In order to help the Member States deploy ERTMS on their rail networks, EU financial support is available for both trackside and on-board investments. Approximately 4 billion euro has been earmarked from the EU budget for this purpose between 2007 and 2020 from two main sources: the Trans-European Network for Transport (TEN-T) Programme14, replaced for 2014-2020 period by the Connecting Europe Facility15, and the Cohesion Policy (the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF)16, the Cohesion Fund17 and the European Structural and Investment Funds (ESIF)18) (see Table 1).

| Source of funding | 2007-2013 | 2014-2020 | Co-financing rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| TEN-T/CEF | 645 | 850 | Up to 50 % |

| ERDF/Cohesion Fund/ESIF | 570 | 1 900 | Up to 85 % |

| Total | 1 215 | 2 750 |

Source: European Court of Auditors based on the data from the European Commission.

15The two main sources of EU funding for ERTMS projects are managed under direct or shared management:

- Under direct management (TEN-T and CEF) the Commission is responsible for approving each individual project submitted by the authorities of the Member States. Technical and financial implementation of co-financed projects is the responsibility of the Innovation and Networks Executive Agency (INEA), under the supervision of the Directorate-General for Mobility and Transport of the European Commission.

- Under shared management (ERDF and Cohesion Fund) projects are generally selected by the national managing authorities. The Commission (the Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy) examines and approves the financial contribution to major projects, i.e., projects whose total eligible cost exceeds 50 million euro for the period 2007-2013 and 75 million euro for the period 2014-2020.

The EU budget mostly co-finances two types of project in relation to ERTMS: trackside (equipping rail tracks with the necessary equipment), and on-board (equipping locomotives with ERTMS units). Other co-financed projects consisting of testing, developing specifications or corridor approach projects may also be eligible for support.

17Moreover, in addition to the sources previously mentioned, additional funding can be provided by the Shift2Rail Joint Undertaking19 which was established in 2014 (see paragraph 65). It aims to invest almost one billion euro in research and innovation in 2014-2020 (450 million euro from the EU budget, supplemented by 470 million euro from industry). ERTMS research projects are eligible within the scope of its activities. The European Investment Bank (EIB) provides loans and guarantee schemes for ERTMS trackside deployment and purchase of new rolling stock equipped with ERTMS.

Audit scope and approach

18In this audit we assessed whether ERTMS had been properly planned, deployed and managed and whether there was an individual business case. To do this, we examined:

- whether ERTMS had been deployed in a timely and effective manner based on proper planning and a proper cost estimate;

- whether there was a business case for individual infrastructure managers and railway undertakings;

- whether EU funding had been effectively managed to contribute towards ERTMS deployment.

During our audit we visited six Member States: Denmark, Germany, Spain, Italy, the Netherlands and Poland. Altogether, these Member States partly cover all nine core network corridors where ERTMS has to be fully deployed by 2030. We held interviews with the authorities of Member States (ministries in charge of transport and infrastructure investments, infrastructure managers and national safety authorities), passenger and freight rail operators, fleet owners and other stakeholders (notified bodies, various national and European rail associations).

20We also examined the role played by the Commission and ERA in planning, managing, deploying and financing ERTMS. We held interviews with the Commission (Directorate-General for Mobility and Transport, Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy and INEA), the European ERTMS Coordinator and ERA. Additionally, public information on ERTMS deployment outside the EU (e.g. Switzerland) was also examined.

21Our assessment of ERTMS planning, deployment and management in the EU and, in particular, in the six Member States visited, is also based on a review of a sample of 51 EU co-financed projects related to ERTMS from the 2007-2013 programme period. The total EU-co-financing allocated to the ERTMS component of these projects amounts to approximately 540 million euro, which is around 14 % of all estimated ERTMS funding for the years 2007-2020. Out of 51 projects, 31 projects related to trackside investments and 20 projects to on-board equipment. Annex III contains the list of projects examined.

Observations

ERTMS was a strategic political choice and was launched with no overall cost estimate or appropriate planning for its deployment

ERTMS concept generally is not disputed by the rail sector

22Notwithstanding the big challenges presented in this report, during the audit we found that the idea of a single signalling system, to foster rail interoperability, as the backbone of the single European railway area, was generally not disputed by the rail sector (infrastructure managers, railway undertakings, national safety authorities, suppliers and other stakeholders). Depending on the performance and obsolescence of the existing national signalling systems, ERTMS has a potential to improve the capacity and speed of rail transport. If fully deployed, ERTMS would contribute towards making rail more competitive compared with other modes of transport in accordance with the objectives of the 2011 White Paper20 and would help achieve EU environmental targets.

23In addition to enhanced interoperability, and depending on the performance of the existing national signalling systems and their varying degree of obsolescence, other potential advantages are the following:

- increased capacity: ERTMS can reduce the minimum distance or time between vehicles in commercial service allowing more trains to be run on highly congested rail lines;

- increased commercial speed;

- continuous supervision of train speed with benefits for safety;

- lower maintenance costs for infrastructure managers and

- increased product harmonisation and competition among suppliers

We found that in the visited Member States ERTMS is already now resulting in some benefits for the infrastructure manager and/or the railway undertakings. For example, in Spain, ERTMS performs better than the national signalling system in terms of speed (300-350 km/h as against 200 km/h) and capacity, especially on suburban commuter lines in Madrid and Barcelona.

25Moreover, ERTMS is being deployed in other European countries outside the EU, such as Switzerland (see Box 2), as well as in a number of countries worldwide, usually without EU funding. ERTMS investments outside Europe represent 59 % of the overall ERTMS investment in terms of rail lines and 33 % in terms of on-board units. Unlike in the EU, ERTMS deployment projects abroad are generally greenfield investments (i.e. no previous signalling system was in place) made within one single country and by one railway company. This significantly facilitates its deployment.

Box 2

ERTMS deployment in Switzerland

Switzerland has launched an ambitious ERTMS investment plan to increase capacity and train speed on the busiest segments of the national railway network. For instance, the 45 km-long Mattstetten-Rothrist line is a strategic bottleneck for traffic from Bern to Basel, Zurich, and Lucerne. Equipping this section with ERTMS level 2 has reduced journey time between Zurich and Bern by 15 minutes (from 70 minutes to less than one hour) and headways between trains have been reduced to 110 seconds and train speeds have increased to 200 km/h.

ERTMS deployment was a strategic political choice with no overall cost estimate

26The ERTMS concept as a single signalling system in Europe stems from the strategic political choice, made in the 1990s, to create a single European railway area. The first legal obligation was included as early as 1996 and this was followed by multiple legislative acts making ERTMS deployment compulsory for both high-speed and conventional rail. However, these legal obligations were not based on an overall cost estimate establishing the necessary funding and its sources21.

27It was only in 2015 that the Commission started to assess the cost of ERTMS deployment (see paragraph 47). This exercise was limited to assessing the equipment and its installation cost and was restricted to the core network corridors. The Commission made no assessment for the entire core and comprehensive network, where ERTMS is to be deployed by 2030 and 2050 respectively.

28We found that the deployment of ERTMS (in combination with the required associated works22) both on tracks and on-board turned out to be a costly exercise. The extrapolation of the cost of two visited Member States (Denmark and the Netherlands), which opted for ERTMS on a network scale shows that the overall cost of deploying ERTMS could be up to 80 billion euro by 2030 for the core network corridors or up to 190 billion euro by 2050 when the comprehensive network is expected to be equipped with ERTMS (see paragraph 55). Such works, however, may also be required if systems other than ERTMS replace obsolete signalling equipment or to address maintenance backlogs. The overall cost may decrease over time due to future technological development, economy of scale and increased competition among ERTMS suppliers.

A thicket of legal obligations, priorities and deadlines

29In the course of the last 20 years, numerous legal documents have set obligations related to the deployment of ERTMS. There have also been attempts to prioritise specific lines and set differentiated deadlines. However, there has been little coordination between these obligations, priorities and deadlines and this has hindered a coherent deployment of ERTMS (see also paragraph 36 and 40).

30The obligation to deploy ERTMS starts with Directive 96/48/EC, which makes it one of the basic principles for the interoperability of high-speed lines. The same principle is included for conventional rail in Directive 2001/16/EC, which states that ‘all new infrastructure and all new rolling stock manufactured or developed after adoption of compatible control and command and signalling systems must be tailored to use of those systems’. The first technical specifications for interoperability concerning ERTMS, which are compulsory for both high-speed and the conventional rail, were made legally binding in 2002; these were followed by subsequent technical amendments. Furthermore, Decision 2012/88/EU23 requires the installation of ERTMS for all rail projects funded with EU money regardless of their location. New or renovated lines have to be equipped with ERTMS even where the deadline for deployment of such lines is 2050 or beyond, according to the TEN-T regulation (see paragraph 75).

31As far as on-board deployment is concerned, the decision requires new locomotives and other new railway vehicles ordered after 1 January 2012 or put into service after 1 January 2015, to be equipped with ERTMS, with the exception of regional traffic.

32The first official deadlines for ERTMS deployment are set out in the 2009 European Deployment Plan (EDP), which was limited to six ERTMS corridors, indicating that 10 000 km of trackside should be equipped with ERTMS by 31 December 2015 and 25 000 km by 31 December 2020. As of late 2016 only around 4 100 km were equipped with ERTMS (see paragraph 36). In early 2017 the Commission revised these targets in the new European Deployment plan (EDP) and postponed the deadlines beyond 2015, up to 2023, whereas the remaining sections will only be deployed after 2023, without any fixed and coordinated deadlines (with the exception of the overall deadline of 2030).

33In addition, the TEN-T regulation established a deadline of 31 December 2030 to equip the entire core network of 66 700 km with ERTMS (including nine core network corridors accounting for approximately 51 000 km) and 31 December 2050 for all 123 000 km of the comprehensive network (see Table 2). We found that no interim targets for monitoring have been set for overall ERTMS deployment by 2050. These deadlines and specific sections of lines to be equipped with ERTMS may be subject to change and moving targets as it is envisaged that the newly adopted European Deployment Plan and TEN-T regulation will be revised by 2023.

| Core network corridors | Core network | Comprehensive network1 | Whole EU rail network | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length (km) | 51 000 | 66 700 | 123 000 | 217 000 |

| Deadline | 2030 | 2030 | 2050 | No deadline |

1The comprehensive network includes the core network and the core network corridors (see paragraph 12).

Source: European Court of Auditors based on data of the European Commission and TEN-T Regulation (EU) No 1315/2013.

No deadline is set for decommissioning current national signalling systems

34The EU Member States have adopted different strategies for the deployment of ERTMS on their rail network. Among the Member States visited only Denmark has chosen to dismantle its national system and roll-out ERTMS as a single signalling system on the majority of its national rail network, taking into account shortcomings and obsolescence of its current national signalling system. All the other Member States visited have opted for ERTMS as an add-on software based-system for their national signalling systems, in particular where their remaining lifetime is 15-20 years (for example, in Germany).

35For ERTMS to be a single signalling system in the EU, national signalling systems must be decommissioned. Neither 2009 EDP nor the new EDP includes any strategy for decommissioning national signalling systems. At the time of the audit, no deadline for decommissioning the national signalling systems in the Member States had been established. However, the Member States are obliged to inform the Commission about their deadlines of decommissioning via national implementation plans, due to be submitted to the Commission in July 201724. Notwithstanding the challenges of introducing a coordinated obligation binding on all the Member States, the absence of such information is a significant obstacle that stands in the way of long-term investment planning by railway undertakings nor does it help to accelerate ERTMS deployment across the EU.

So far limited and patchy deployment of ERTMS

36As compared with the targets set (see paragraph 32), out of 51 000 km of core network corridors to be equipped by 2030, only 4 121 km of ERTMS were in operation as of the end of 2016. This only represents around 8 % of the core network corridors. Out of nine core network corridors the most advanced is the Rhine-Alpine corridor with 13 % of lines already equipped. ERTMS deployment in other corridors ranges from between 5 % and 12 % (see Figure 4).

Figure 4

ERTMS deployment in core network corridors as of end of 2016 (in km)

Source: European Court of Auditors based on data of the European Commission.

We consider that this low level of deployment of ERTMS puts the achievement of the targets set for 2030 at risk as these targets are unlikely to be met and significantly undermines potential interoperability benefits. A close follow-up by the Commission of the recently adopted EDP is necessary, as it is a prerequisite of successful deployment.

38The status of ERTMS deployment within the core network corridors varies significantly in the EU Member States (see Annex IV). Out of the six Member States visited, the Netherlands and Spain were the only ones that fulfilled the targets set for 2015 in the 2009 EDP.

39The deployment of ERTMS in the rolling stock in the EU is also low, amounting to around 2 700 units, i.e. 10 % of the total EU fleet. Most of the vehicles already equipped belong to the high speed passenger fleet operating mainly in domestic markets.

40Currently ERTMS is deployed in a patchy way, with many stretches not connected to each other (see Figure 5). In addition, although, according to EU policy, the core network corridors should be the main focus of investments, we found cases of single lines outside the core network with no connection to the rest of the respective network or the cross-border section. Although the Commission is the initiator of the ERTMS concept, it has no precise overview of the overall deployment on the European level as its monitoring is limited to the core network.

Figure 5

ERTMS patchwork deployment on core network corridors

Source: European Commission.

In some cases we found a lack of coordination between trackside and on-board ERTMS deployment. For example, in Poland, the rolling stock equipped with ERTMS has been purchased but, in reality, it only actually works on 218 km (out of 3 763 km of its core network corridors), and trains can run at 200 km/h on just 89 km of these. In the remaining cases, trains run with ERTMS switched off, as the remaining trackside infrastructure is not equipped with ERTMS. In practice, the use of ERTMS is as low as 6.5 % per day. In Italy the effective use of ERTMS equipped trains varies between 19 % and 63 % in terms of train/km and it is limited to high speed lines only.

Many infrastructure managers and railway undertakings have been reluctant to invest in ERTMS due to the lack of an individual business case

An overall positive outcome of ERTMS at EU level, but only in the long term

42Possible benefits of ERTMS generally concern society or the rail sector as a whole rather than the individual infrastructure managers and railway undertakings that have to take the investment decision as to whether or not to install ERTMS, and bear its cost.

43In 2016, the Commission developed a positive aggregate business case for ERTMS deployment at the level of each corridor in a business case report on the nine core network corridors25. However, this business case demonstrates that potential benefits will only materialise, in general, in the long term. In addition, this analysis does not indicate if the benefits of ERTMS deployment will make up for its cost for infrastructure managers or railway undertakings, considered individually or even as a category.

Many infrastructure managers and railway undertakings with diverse needs expected to invest in one system

44Based on the current legislation (see paragraph 30 and 31), ERTMS is a compulsory investment for different rail stakeholders with very diverse needs: infrastructure managers with obsolete and under-performing signalling systems, infrastructure managers with relatively new and well-performing signalling systems, freight operators, passenger operators, high-speed rail operators, international and domestic rail operators and others. They are all expected to invest in ERTMS as a single signalling system according to the same statutory deadlines, whereas investments in rail infrastructure and rolling stock are usually made on a long term basis, as the average useful lifetime is around 30 years.

45The willingness of infrastructure managers to invest in ERTMS depends on their starting points. Some infrastructure managers already have well-functioning and relatively new signalling systems which has made them reluctant to invest in ERTMS (for example in Germany), whereas in other Member States, the signalling systems were coming to the end of their life-cycles or their performance in terms of safety or speed was no longer sufficient (for example Denmark, see also Box 3). According to the stakeholders interviewed, the obsolescence of national signalling systems will eventually trigger the overall deployment of ERTMS; however, coordinated timing is a decisive factor for ERTMS to be successfully deployed (see paragraph 70).

Box 3

Two examples of factors determining the decision of infrastructure managers whether to deploy ERTMS or not

In Denmark, an analysis was carried out in 2006 to assess how to re-invest most effectively in the signalling system for the state railway. It concluded that the national system was obsolete and it could only be kept in operation until 2020 at the latest. Hence Denmark was the first country in the EU that decided to roll out ERTMS across the whole state-owned railway network without a fall-back to the national signalling system.

In Germany, it is difficult for the infrastructure manager to build a business case for ERTMS deployment as there are already two well performing systems, LZB and PZB. The LZB system, installed on 2 600 km of tracks, already enables trains to run at a speed of around 300 km/h or on lines with high traffic density, even if it is progressively reaching the end of its life cycle, expected around 2030. The PZB system, covering 32 000 km of conventional tracks, is also considered by the German infrastructure manager to be well-performing in terms of safety, capacity and other performance indicators and it will be available for a longer period of time even though it allows lower speed.

As regards railway undertakings, the need to have ERTMS depends on the types of operations and business that they have. Significant differences are, for example, noted between the needs of ERTMS for high speed and conventional traffic (especially freight for which a maximum speed of around 100 km/h is needed), and between railway undertakings operating almost exclusively in one country and those operating international freight and passenger traffic.

ERTMS investments are costly

47It was only in 2015 and 2016 that the Commission started to assess the cost of ERTMS deployment in two studies26. This assessment was limited to the cost of ERTMS equipment and installation and restricted to the core network corridors. Based on this cost category, the trackside deployment cost could range between 100 000 and 350 000 euro per kilometre, i.e. 5-18 billion euro respectively.

48In order to put ERTMS fully into operation on trackside, the total cost to be borne by the infrastructure managers is not however limited to the cost of equipment and installation, but also includes other associated works required to migrate from a fully-functional national signalling system to a fully-functional ERTMS system. According to the Commission these works are a pre-requisite for deployment, even though they are not formally a part of ERTMS.

49The two Member States visited (Denmark and the Netherlands) which opted to deploy ERTMS on a large scale on their rail network have designed their ERTMS national deployment programmes and drafted their estimated budgets. Based on their estimates, we assessed the magnitude of the investments that may be required in order to have a fully-functional ERTMS trackside across the EU. The total estimated cost includes all necessary components, such as: the renovation of the interlocking system, the design, testing and authorisation of the system, project management, investments related to the telecommunication and radio block centres, the training and re-deployment of staff or migration management. Moreover, ERTMS deployed trackside as an additional system may entail further maintenance costs until the national system is not needed any more and is decommissioned.

50In these two Member States, the total cost of ERTMS deployment trackside amounts to 2.52 billion and 4.9 billion euro for 2 132 and 2 886 km of lines respectively, or an average cost of 1.44 million euro per kilometre of line (see more details in Annex V). A linear extrapolation of these estimates indicates that the total cost of ERTMS deployment trackside throughout the core network corridors or the comprehensive network could range between 73 and 177 billion euro, depending on the extent of the deployment (see Table 3). Technological development and economy of scale might reduce in future the overall cost of the ERTMS deployment.

51In addition to the cost of ERTMS deployment on trackside, which is borne by the infrastructure managers, ERTMS must also be installed on the locomotives, at the expense of railway undertakings. The situation differs for existing locomotives, which have to be retrofitted to be able to run on ERTMS equipped lines, and new locomotives, which are purchased with the ERTMS already installed on-board.

52In the case of existing locomotives, the two aforementioned Commission studies refer to a cost per locomotive between 375 000 euro and 550 000 euro, including ERTMS equipment and installation, testing and authorisation and unavailability of the vehicle. In addition, associated training costs are estimated at 20 000 euro per locomotive. Considering that the number of on-board units to be retrofitted is estimated at 22 000 (see paragraph 39), these figures could translate into an average cost of 11 billion euro for the entire fleet (see details in Annex V). Moreover, the additional ERTMS on-board equipment may result in further maintenance cost per locomotive until the national signalling system is decommissioned.

53During the audit we found that the retrofitment cost varies a lot depending on the number of locomotives to be retrofitted and the number of countries in which they operate. In addition, subsequent statutory ERTMS upgrades, resulting from the constant evolution of the system and the correction of errors in the software, entail further significant costs. In some cases we found that the total cost amounts to almost one million euro per on-board unit, and this excludes the unavailability cost, as shown in Box 4.

Box 4

Example of the total cost of the retrofitment of several series of locomotives

In the Netherlands, one of the reviewed projects concerned the retrofitment of several multi-system freight locomotives with ERTMS, baseline 2.3.0d. The cost of the retrofitment, including compulsory upgrades, ranged between 663 000 and 970 000 euro per locomotive. As soon as the infrastructure manager deploys baseline 3 another compulsory up-grade is expected.

In Germany, another selected project consisted in the retrofitment of several freight locomotives with ERTMS baseline 2.3.0d. The cost ranged between 420 000 and 630 000 euro per locomotive. An up-grade to baseline 3, needed to operate in Germany, would on average result in an additional cost of 270 000 euro per locomotive.

New locomotives or trainsets have to be equipped with ERTMS irrespective whether they run on ERTMS equipped lines or not. The average cost of an on-board unit is estimated by railway undertakings in the Member States visited at approximately 300 000 euro (around 15 % of the cost of the whole locomotive). This investment cost is not included in the overall cost estimate for on-board deployment included in the aforementioned studies.

55Hence, ERTMS, together with the required associated works, entails costly investments which have to be covered by infrastructure managers and railway undertakings. The overall cost of ERTMS deployment, both trackside and on-board, could be up to 80 billion euro for the core network corridors or 190 billion euro for the comprehensive network (see Table 3). Such works, however, may also be required if systems other than ERTMS replace obsolete signalling equipment or to address maintenance backlogs. Since infrastructure managers plan their investments over the time horizon of 30-50 years, and while acknowledging the difficulties in anticipating future technological evolution over such a long period, it is of critical importance to have a cost estimate for the deployment and a reliable planning, including financing coverage, as the EU funding cannot be expected to cover the deployment cost and other sources of funding have to be found (see paragraph 73).

| Core network corridors | Core network | Comprehensive network | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Length (km) | 51 000 | 66 700 | 123 000 |

| Cost extrapolation trackside (billion euro) | 73 | 96 | 177 |

| On-board retrofitment (billion euro) | 11 | ||

| Total (billion euro) | 84 | 107 | 188 |

Source: European Court of Auditors based on a linear extrapolation of the existing national estimates in Denmark and the Netherlands.

Compatibility and stability problems adversely affect the individual business case

Problems of compatibility between different versions of ERTMS

56Compatibility problems may arise mainly as a result of two major factors: the integration of ERTMS with the existing national signalling system in each Member State and the deferred deployment of ERTMS across the borders.

57In the EU ERTMS is embedded in the national rail networks and their signalling systems (i.e. brownfield projects). Due to tailor-made ERTMS solutions in the national rail networks there is currently no ERTMS on-board unit in the EU able to run on all rail sections equipped with different versions of ERTMS. Interoperability issues occur not only in the cross-border sections between Member States, but even within one country (for example, the Netherlands). In addition, we noted that, so far, ERTMS deployment has been limited to lines whereas train stations and hubs have not yet been equipped with ERTMS.

58The Member States opted for the deployment of the ERTMS system at different stages of its development and on various railway lines within their national networks. The technical specifications for interoperability have evolved at a very rapid pace hampering the overall stability of the system (on average they have been changed every two years) and resulting in the need for subsequent upgrades. For example, although baseline 2.3.0d was issued in 2008, and is still valid today, baseline 3 was being developed and prioritised for deployment in the meantime27. Locomotives equipped with ERTMS baseline 2 will not be able to run on tracks equipped with baseline 3. The stakeholders expect that this problem will be mitigated in the future as baseline 3 on-board units should be able to run on baseline 2 trackside (see Box 5).

Box 5

Examples of compatibility problems

In Italy, 366 km of high-speed lines are equipped with baselines preceding baseline 2.3.0d and will have to be upgraded in the near future to enable new trains to run on them. In addition, conventional lines are supposed to operate with baseline 3. The locomotives equipped with baseline 2.3.0d will not be able to run on these lines. Some of them have already been upgraded with the support of EU co-financing.

In Spain, the first lines were equipped with baseline 2.2.2+. Spain has already upgraded some but further efforts will have to be made to migrate these lines to 2.3.0d. At the time of the audit, 1 049 km out of 1 902 km of lines still needed to be upgraded (55 %). Similarly, 158 out of 362 already equipped vehicles now need to be upgraded to be kept operational.

Need for the industry to deliver a harmonised version

59The lack of compatibility of the ERTMS equipment is also the result of the fact that the industry prepares tailor-made solutions adapted to the specific requirements of each Member State, which are not always compatible. Potential problems and errors are usually not publicly communicated and this affects the learning curve and makes it difficult to find common solutions.

60Additionally, taking into account the large scale of the investments that are planned in the near future under the new EDP, there is a risk that the industry may not be ready to deliver a stable harmonised version of the equipment. The capacity of the industry to deliver the product will depend on the customisation level of the specific tenders launched by the infrastructure managers and railway undertakings. National variations may further increase both costs and risks to interoperability.

Lengthy certification procedures to ensure compatibility

61The certification of ERTMS involves notified bodies, which are responsible for testing and certification, and national safety authorities, which issue authorisations. In order to obtain a certificate for a line or an on-board unit the infrastructure managers and railway undertakings usually cooperate closely with the national safety agency from the very beginning of the project, before a formal application is submitted (the so-called pre-engagement procedure).

62During the audit we found that the certification and authorization processes were relatively lengthy and required on average one-two years, depending on the length of these unofficial technical pre-engagement procedures. In the case of cross-border operations we found that the certification of on-board units was particularly complex and costly due to national variations which also hindered the cross-acceptance of work performed by the national safety authorities in other Member States (see Figure 6).

Figure 6

Cross-acceptance of vehicle

Source: European Court of Auditors.

Enhanced role of ERA a positive move towards the single European railway area

63The recent legislative developments, resulting in a stronger role for ERA are a positive move towards a single European railway area. The Fourth Railway Package entrusts ERA, as a formal system authority for ERTMS, with the tasks of issuing EU-wide safety certificates for railway undertakings and authorisations for vehicles and ERTMS subsystems used in more than one Member State, as well as verifying technical trackside solutions included in tenders submitted by the infrastructure managers from mid-2019 onwards. In addition, ERA will have an increased supervisory role over the notified bodies and national safety agencies and assess tender documentation for trackside deployment in the EU.

64However, there are still significant challenges which put the deployment of ERTMS at risk. These particularly concern:

- ERA’s administrative capacity as the ERTMS system authority for an overall project amounting to hundreds of millions of euro and its enhanced role under the 4th Railway Package;

- the need for practical guidelines and training reducing the steep and costly learning curve in the practical design and deployment of ERTMS in the Member States;

- the increased ERA’s role in the supervision of notified bodies and national safety agencies and its ability to verify ERTMS technical trackside solutions as it might not to be possible for ERA to anticipate any compatibility issue with applicable TSIs from tendering documents;

- the mechanism for appeals and reporting on low quality certificates, which needs to be standardised as do the ERTMS tests to be performed on tracks at EU level as is already the case for rolling stock.

In 2014, a joint undertaking Shift2Rail was established as a public- private partnership to contribute towards the achievement of a single European railway area. We noted that ERA has a limited observer role in its governing board and that there is a need for closer cooperation between Shift2rail and ERA. Therefore, there is a risk that ERA may miss the opportunity to act early when monitoring and consulting Shift2Rail on its deliverables, particularly taking into account that, in addition to primary research, the joint undertaking is also involved in developing products, such as an automatic train operation for future ERTMS baselines. The compatibility of the development of new ERTMS functions with current technical specifications for interoperability is vital to ensure interoperability in the future.

New European Deployment Plan is a step forward but major challenges remain

66Although it turned out that the deadlines set in the 2009 European Deployment Plan for ERTMS deployment were unlikely to be met, the Commission decided not to enforce infringement procedures against any Member States that had not fulfilled their obligations in terms of deploying ERTMS on the corridor sections. Instead, in December 2014, the Commission and the European Coordinator for ERTMS launched the Breakthrough Programme28 to accelerate ERTMS implementation across the EU with a view to adopting a new deployment plan.

67This programme was negotiated with the Member States at a high level. The discussions were held between the European Coordinator and national ministries and infrastructure managers. Based on the Breakthrough Programme and following the negotiations the Commission drafted the new European Development Plan in the form of a legislative act directly applicable to the EU Member States. It was officially published on 5 January 201729.

68The new European Deployment Plan, which is supported by the Member States, is a step towards more realistic deployment, but major challenges remain. Firstly, as in the past, it does not include any overall cost assessment for ERTMS deployment. Secondly, it is in no way linked to any dedicated funding nor is the source of this funding defined; hence other incentives have to be found for the sector to meet its targets. In addition, there is still no legally binding deadline for decommissioning the current national systems with a view to making ERTMS a sole (and not additional) signalling system.

69As regards the long-term predictability needed for the railway undertakings to plan their investments, the new EDP only refers to specific trackside deployment targets between 2017 and 2023, whereas the remaining sections to be equipped are only shown as ‘beyond 2023’, with no fixed deadline (except for the general deadline of 2030). This affects the coordination of deployment among Member States and discourages railway undertakings from planning their on-board investments accordingly. We also found that over the next five years the expected revisions of the legislative acts (see paragraph 33) make it particularly difficult for railway undertakings to make a long term investment decision.

70Moreover, the planned deployment set out in the newly adopted EDP is affected by a lack of time alignment between Member States on cross-border sections. This shows that Member States plan their deployment according to their national needs, regardless of any commitment made in relation to EU priorities. For example, according to current plans, Germany intends to equip only 60 % of its railway lines on core network corridors by 2030, without reaching 100 % completion on any of them.

EU funding can only cover a limited amount of the costly investment, and has not always been properly managed and targeted

EU funding available for ERTMS deployment can only cover a limited amount of the investments

71Approximately 1.2 billion euro was allocated from the EU budget for ERTMS trackside and on-board investments between 2007 and 2013 from two main sources: TEN-T Programme, which amounted to 645 million euro and the Structural Funds (the ERDF and the Cohesion Fund), estimated at 574 million euro (the ERTMS component is estimated at 10 % of major rail investments).

72During the 2014-2020 programme period the EU budget continues to support ERTMS deployment with an estimated total budget of 2.7 billion euro. Regarding the CEF, there have been three dedicated calls for project applications, for an overall amount of 850 million euro from the CEF for ERTMS projects until 202030. ERTMS projects can also benefit from the European Structural and Investments Funds (ESIF) support, in the eligible regions, up to 1.9 billion euro31.

73EU funding available for ERTMS only represents a limited percentage of the overall cost of deployment with most of the financing to be found from other sources. As described in paragraph 55, the cost of ERTMS deployment on core network corridors (both trackside and on-board) is in the order of 90 billion euro. EU financial support for ERTMS projects during the 2007-2020 period amounts to 4 billion euro, or less than 5 % of the total cost of ERTMS deployment on core network corridors.

74In the last two CEF calls for project applications, the value of submitted project proposals exceeded the available funding by 5.6 and four times respectively (the third call for applications had not yet been evaluated at the time of the audit). Thus, even if 100 % of the EU funding is successfully taken up, the infrastructure managers and railway undertakings will still need to cover the outmost majority from other financing sources in order to deploy ERTMS across the EU.

Different issues with ERTMS projects related to the management mode

Lack of monitoring and limited use of EU funding in shared management

75We found that, unlike INEA for TEN-T and CEF projects, the Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy does not involve ERA or external experts in order to assess the compliance of implemented projects with the technical specifications for interoperability. Therefore there is a risk of potential problems involving the compatibility of the different versions of ERTMS installed.

76In the case of Cohesion policy projects, ERTMS investment is usually part of the renovation or construction of a rail section. The signalling equipment is only installed at the final stage of the process. Such projects may experience delays, reaching in some cases the end of eligibility period. As a result, the projects need to be financed from the next programme period as happened in Poland. Therefore, in practice, the use of EU funding for ERTMS investments in the 2007-2013 period was limited (see Annex III).

Significant decommitment levels in direct management

77Although the value of submitted project applications exceeded the available funding (see paragraph 74), the original TEN-T allocations32 to ERTMS projects had been subject to significant decommitments during the 2007-2013programme period. Overall in the EU, 50 % of TEN-T funds originally allocated to ERTMS projects were decommitted (see Table 4) and only 218 million euro out of 645 million euro (34 %) had already been paid out at the time of the audit. The decommitment rate goes up to 86 % for the six Member States selected for the audit33.

| Member State | Denmark | Italy | Germany | Spain | Poland | Netherlands | Six Member States selected | Total EU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ratio of decommitment | 100 % | 94 % | 92 % | 83 % | 75 % | 38 % | 86 % | 50 % |

Source: European Court of Auditors calculations based on data of INEA as of January 2017.

78The main reason for these decommitments is the fact that EU financial provisions are not aligned with the life cycle of ERTMS projects, which can be affected among others by long testing and certification procedures or changes in the technical specifications and national implementation strategies. Delays in implementation or reductions in the original project scope resulted in the full or partial decommitment of funding, as it was not possible for the beneficiaries to complete the project within the eligibility periods set in the calls for proposals.

79There is a risk that CEF funds may also be decommitted during the 2014-2020 programme period. At the time of the audit, the payments made amounted to 50 million euro out of the 689 million euro allocated (7.3 %). Four projects, accounting for a total EU support of 30.7 million euro, were cancelled even before they had obtained any pre-financing and the grant agreement had been signed due to a change of implementation plans or excessively high costs requested by suppliers.

80EU funds that have been decommitted at an early stage of the programme period can be used again to finance other ERTMS projects. However, the Commission does not have a clear view of how much of the amounts recovered from ERTMS actions were actually re-allocated to ERTMS. All EU funds already decommitted or to be decommitted at a later stage in the programme period (i.e. after 2013), are transferred back to the general EU budget, thus reducing the availability of EU funds for ERTMS deployment.

EU funding has not always been well targeted

On trackside, limited focus on cross-border sections and core network corridors, especially in Cohesion policy

81The EU funding was not always concentrated on core network corridors as is shown in our analysis of the projects selected for the audit (see paragraph 86). This is particularly the case for Cohesion policy support as installing ERTMS is compulsory whenever renovating or building a new rail line regardless of the project location. This does not comply with the prioritisation of corridors (i.e. ERTMS corridors or core network corridors) promoted by the Directorate-General for Mobility and Transport (see paragraph 30) and may lead to ineffective use of EU funds, as a line which needs to be equipped under Cohesion policy might not use ERTMS in practice for a long time and then need a subsequent upgrade of the signalling system.

82As regards border crossing, only limited EU support was allocated for cross-border trackside sections despite EU policy and the Court’s recommendations in 2005 and 2010: in six visited Member States out of 31 trackside projects selected for the review only six concerned cross-border sections, however, two of these projects were cancelled (Germany).

83As far as the Member States selected for this audit are concerned, in Germany ERTMS has not been put into commercial operation on any cross-border section, whereas Austria, Belgium and the Netherlands have already equipped some sections at their borders with Germany. The Netherlands have also equipped the cross-border section with Belgium and Spain has one operational cross-border section with France whereas at the time of the audit, Denmark, Italy and Poland had not yet equipped any of their cross-border sections on core network corridors.

EU funding available for on-board units mostly taken up by domestic traffic

84EU financial support allocated to on-board units is mostly taken up by the railway undertakings which for passenger traffic run almost exclusively on domestic lines. In the case of the six Member States visited, 70 % of TEN-T and CEF support for on-board units during the 2007-2015 period was allocated to railway undertakings operating passenger domestic traffic. Rail freight traffic, which is more likely to be involved in international traffic, accounted for the remaining 30 % of the available support.

85In addition, freight locomotives are not supported by Cohesion policy funding for retrofitment. Only passenger vehicles, used for domestic traffic under the public service obligation scheme and generally owned by the incumbent rail operator, can potentially benefit from this source of EU support for the purchase of new or upgrade of existing rolling stock.

Status of EU-co-financed projects examined during the audit: delays, decommitments and inaccurate targeting

86At the time of the audit, 14 out of 31 trackside projects selected had been completed, although five were late and one had been completed with a reduced scope. 13 projects were on-going, including three that were subject to delays which, in one case, had led to the full decommitment of the EU funding. Four projects were cancelled and the EU funding was consequently decommitted. Six out of 31 trackside projects were not or only partially implemented on TEN-T corridors. This was particularly the case for Cohesion policy projects (four out of 11 projects).

87As regards on-board equipment, 16 out of 20 projects had been completed, including nine with delays and three with a reduced scope. Two projects were on-going, but in one case the delay resulted in EU funding being decommitted and in another case the project was both delayed and had had its scope reduced. Two projects were cancelled and the EU funding was fully decommitted. For detailed information see Annex III.

Conclusions and recommendations

88Overall, the Court found that the deployment of ERTMS had been based on a strategic political choice and had been launched with no overall cost estimate or appropriate planning for a project worth up to 190 billion euro by 2050. Despite the fact that the ERTMS concept and the vision of enhancing interoperability are not generally questioned by the rail sector, so far ERTMS deployment has been low and patchy. The current status of ERTMS deployment can mainly be explained by the reluctance of many infrastructure managers and railway undertakings to invest in ERTMS equipment due to the costly investment entailed and the lack of an individual business case for many of them (for example in the Member States with well performing national systems and significant remaining lifetime). Even if EU funding could be better managed and targeted, it can only cover a limited amount of the costly investment.

89This creates risks not only for the achievement of the ERTMS deployment targets set for 2030 and the investments made so far, but also for the realization of a single European railway area which is one of the major policy objectives of the European Commission. It may also adversely affect the competitiveness of rail transport as compared with road haulage.

ERTMS was a strategic political choice and was launched with no overall cost estimate or appropriate planning for its deployment

90Despite the political decision to deploy a single signalling system in the whole of the EU, no overall cost estimate was performed to establish the necessary funding and its sources, even though the project is costly. The legal obligations introduced did not require the decommissioning of the national signalling systems, and these obligations are not aligned with deadlines and priorities included in the EU transport policy. At the time of the audit, the level of ERTMS deployment across the EU was low.

Recommendation 1 – Assessment of ERTMS deployment costs

The Commission and the Member States should analyse the total cost of ERTMS deployment (both trackside and on-board) by Member State, taking into account the core network and comprehensive network in order to introduce a single signalling system throughout the EU, given that the time horizon for this type of investment is 30-50 years. The assessment should not only include the cost of ERTMS equipment and its installation, but also all other associated costs based on the experience gained in front runner Member States deploying ERTMS on a large scale.

Deadline: by the end of 2018.

Recommendation 2 – Decommissioning of national signalling systems

The Commission should seek agreement with the Member States on realistic, coordinated and legally binding targets for decommissioning the national signalling systems so as to avoid ERTMS becoming just an additional system to be installed.

Deadline: by the end of 2018.

Many infrastructure managers and railway undertakings have been reluctant to invest in ERTMS due to the lack of an individual business case

91Even though ERTMS could result in an overall positive outcome at EU level in the long run, many infrastructure managers and railway undertakings have been reluctant to invest in it because of the lack of an individual business case. ERTMS is a single system for multiple infrastructure managers and railway undertakings with diverse needs, but it entails costly investments with, generally, no immediate benefit for those who have to bear the cost. Problems with the compatibility of the different ERTMS versions installed and the lengthy certification procedures also adversely affect the individual business case for infrastructure managers and railway undertakings. Notwithstanding the new European Deployment Plan, major challenges to successful ERTMS deployment remain. It is important that ERA has the administrative capacity to act as the ERTMS system authority, taking into account its enhanced role and responsibilities under the Fourth Railway Package.

Recommendation 3 – Individual business case for infrastructure managers and railway undertakings

The Commission and the Member States should, together with rail stakeholders and the ERTMS supply industry, examine diverse financial mechanisms to support individual business cases for ERTMS deployment without any further excessive reliance on the EU budget.

Deadline: by mid-2018.

Recommendation 4 – Compatibility and stability of the system

- The Commission and ERA should, with the support of the supply industry, keep the ERTMS specifications stable, correct the remaining errors, eliminate the incompatibilities between the different ERTMS trackside versions already deployed and ensure future compatibility for all ERTMS lines. In order to do so, ERA should proactively engage in co-operation with the infrastructure managers and national safety authorities prior to the legal deadline in June 2019.

Deadline: with immediate effect.

- The Commission and ERA should, in strong coordination with the supply industry, set a road map for developing a standardised on-board unit able to run on all ERTMS equipped lines.

Deadline: by mid-2018.

- The Commission and ERA should work together with the industry to initiate and steer the development and promote the use of standard tendering templates for ERTMS projects available to all infrastructure managers and railway undertakings to ensure that the industry only delivers compatible ERTMS equipment.

Deadline: by mid-2018.

- The Commission and ERA should facilitate the learning process for persons involved in ERTMS deployment and operation in each Member State so as to reduce the steep learning curve, by exploring different solutions, such as coordinated trainings or exchange of information and guidelines.

Deadline: by mid-2018.

Recommendation 5 – Role and resources of ERA

The Commission should assess whether ERA has the necessary resources to act as an efficient and effective system authority and fulfil its enhanced role and responsibilities on ERTMS under the Fourth Railway Package.

Deadline: by mid-2018.

Recommendation 6 – Alignment of national deployment plans, monitoring and enforcement

- Member States should align their national deployment plans, in particular, when a deadline shown in the new European Deployment Plan is beyond 2023. The Commission should closely monitor and enforce the implementation of the new EDP. Whenever possible, Member States should synchronise the deployment deadlines for earlier cross-border projects, so as to avoid a patchwork deployment of ERTMS.

Deadline: with immediate effect.

- In view of long planning horizons in the ERTMS sector (going up to 2050), the Commission, in consultation with the Member States, should set milestones to allow proper monitoring of the progress.

Deadline: for the core network, by the end of 2020. For the comprehensive network, by 2023.

EU funding can only cover a limited amount of the costly investment, and has not always been properly managed and targeted

92EU financial support is available for ERTMS investments both trackside and on-board, but it can only cover a limited amount of the overall cost of deployment. It leaves most of the investment to individual infrastructure managers and railway undertakings, which do not always benefit, at least immediately, from the deployment of ERTMS. In addition, not all EU funding available for ERTMS was ultimately allocated to ERTMS projects and it was not always well targeted.

Recommendation 7 – Absorption of EU funds for ERTMS projects

The Commission should adapt the CEF funding procedures to better reflect the life-cycle of ERTMS projects so as to significantly reduce the level of decommitments and maximise the use of EU funding available for ERTMS investments.

Deadline: starting from 2020.

Recommendation 8 – Better targeting EU funding

The Commission and Member States should target EU funding available for ERTMS projects better in cases of both shared and direct management:

- when allocated to trackside equipment, it should be limited to cross-border sections or core network corridors, in line with the EU transport policy priorities;

- when allocated to on-board equipment, priority should be given to rail operators who are mostly involved in international traffic so as to encourage intramodal and intermodal competition.

Deadline: with immediate effect for new project applications.

This Report was adopted by Chamber II, headed by Mrs Iliana IVANOVA, Member of the Court of Auditors, in Luxembourg at its meeting of 12 July 2017.

For the Court of Auditors

Klaus-Heiner LEHNE

President

Annexes

Annex I

List of national signalling systems in the EU Member States

Source: ERA.

Annex II

ERTMS technical description

ERTMS is based on the Technical Specification for Interoperability for ‘Control-Command and Signalling’ (TSI CCS), developed by ERA. It can be installed both as an add-on (or overlay) to an existing signalling system or as a single system to be installed for new radio-based infrastructure.

In order to make ERTMS function both the trackside and the train must be equipped with it. The system installed on trackside and the system installed on the vehicles exchange information which makes it possible continuously to supervise the maximum speed allowed for operation, giving the driver all the information needed to operate with cab signalling. The two main components of ERTMS are the European Train Control System (ETCS), deployed trackside in the form of a balise and the Global System for Mobile communications-Rail (GSM-R), a radio system providing voice and data communication between the track and the train.

Currently there are three levels of ERTMS, depending on how the trackside is equipped and the way in which the information is transmitted to the train, and several versions, known as ‘baselines’, as the system is constantly evolving as the result of technological development.

The ETCS levels are as follows:

- Level 1 involves the continuous supervision of train movement but a non-continuous communication between the train and trackside (normally by means of Euro-balises). Lineside signals are necessary.

- Level 2 involves continuous supervision of train movement and continuous communication, provided by GSM-R, between both the train and the trackside. Lineside signals are optional.

- Level 3, provides continuous train supervision with continuous communication between the train and trackside and no need for lineside signals or train detection systems on the trackside other than the Euro-balises. This level was not yet operational at the time of the audit.

A baseline is a set of documents with a concrete version listed in the TSI CCS, i.e. the specifications for many aspects, components, interfaces, etc. concerning ERTMS. Baseline 2, was the first complete set of requirements to be adopted at European level that was considered to be interoperable. Baseline 3 is a controlled evolution of Baseline 2 which includes new additional functions and has been designed to provide backward compatibility with Baseline 2.

Annex III

List of projects examined

Annex IV

ERTMS deployment in core network corridors by Member States as of end of 2016

Source: European Commission.

Annex V

Methodology for the linear extrapolation of ERTMS deployment cost

Source: European Court of Auditors based on a linear extrapolation of the existing national estimates in Denmark and the Netherlands.

Glossary

Baseline: A stable kernel in terms of system functionality, performance and other non-functional characteristics.

Cohesion Fund: The Cohesion Fund aims at strengthening economic and social cohesion within the European Union by financing environment and transport projects in Member States with a per capita GNP of less than 90 % of the EU average.

Connecting Europe Facility (CEF): Since 2014, the Connecting Europe Facility (CEF) has provided financial aid to three sectors: energy, transport and information and communication technology (ICT). In these three areas, the CEF identifies investment priorities that should be implemented in the coming decade, such as electricity and gas corridors, the use of renewable energy, interconnected transport corridors, cleaner modes of transport, high-speed broadband connections and digital networks.

European Deployment Plan (EDP): A document that was finally agreed in 2009 and included in Commission Decision 2009/561/EC on the technical specifications for interoperability. The aim of the EDP is ‘to ensure that locomotives, railcars and other railway vehicles equipped with ERTMS can gradually have access to an increasing number of lines, ports, terminals and marshalling yards without needing national equipment in addition to ERTMS’.

European Rail Traffic Management System (ERTMS): A major European industrial project which aims to replace the different national train control and command systems. It has two basic components, an automatic train protection system (ATP) to replace the existing national ATP-systems, the European Train Control System (ETCS); and a radio system for providing voice and data communication between the track and the train, based on standard GSM technology, but using frequencies specifically reserved for rail (GSM-R).

European Union Agency for Railways (ERA): Previously European Railway Agency, established in 2004 with the objective of developing the technical specifications for interoperability, including ERTMS and to contributing towards the effective functioning of a Single European Railway Area without frontiers. The ERA’s main task is to harmonise, register and monitor technical specifications for interoperability (TSIs) across the entire European rail network and set common safety standards for European railways. The ERA itself has no decision-making powers, but it helps the Commission to draw up proposals for decisions.

European Regional Development Fund (ERDF): The European Regional Development Fund aims to reinforce economic and social cohesion within the European Union by redressing the main regional imbalances through financial support for the creation of infrastructure and productive job-creating investment, mainly for businesses.

European Structural and Investment Funds (ESIF): These are five separate funds that aim to reduce regional imbalances across the Union, with policy frameworks set for the seven-year budgetary period. The funds are the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) the European Social Fund (ESF), the Cohesion Fund (CF) the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD) and the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund (EMFF).

Incumbent operator: The rail operator with a historically dominant position in the national market, deriving from a single integrated company which used to be responsible for the management of the rail infrastructure and provision of transport services.

Infrastructure manager: A body or undertaking responsible in particular for establishing, managing and maintaining railway infrastructure.

Interoperability: Interoperability is defined as the capability to operate on any stretch of the rail network without any difference. In other words, the focus is on making the different technical systems on the EU’s railways work together.

Innovation and Networks Executive Agency (INEA): The Innovation and Networks Executive Agency (INEA) is the successor of the Trans-European Transport Network Executive Agency (TEN-T EA), which was created by the European Commission in 2006 to manage the technical and financial implementation of its TEN-T programme. INEA, with its headquarters in Brussels, officially started its activities on 1 January 2014 in order to implement parts of the Connecting Europe Facility (CEF), Horizon 2020, and other legacy programmes (TEN-T and Marco Polo 2007-2013).

Notified Body: A body designated by a Member State which is involved in verifying conformity of subsystems with technical specifications for interoperability and draws up the EC certificate of verification. The task of the notified body begins at the design stage and covers the entire manufacturing period through to the acceptance stage before the subsystem is placed in service.

Rail signalling system: A system used to manage railway traffic safely and keep trains clear of each other at all times.

Railway undertaking: A public or private rail operator licensed according to applicable EU legislation, the principal business of which is to provide services for the transport of goods and/or passengers by rail. In this report, it also covers fleet owners such as train asset leasing companies.

Trans-European Transport Networks (TEN-T): A planned set of road, rail, air and water transport networks in Europe. The TEN-T networks are part of a wider system of Trans-European Networks (TENs), including a telecommunications network (eTEN) and a proposed energy network (TEN-E). The infrastructure development for TEN-T is closely linked with the implementation and further advancement of EU transport policy.

Endnotes