The certification bodies’ new role on CAP expenditure: a positive step towards a single audit model but with significant weaknesses to be addressed

About the report: This audit examined the role of the Certification Bodies which provide opinions on the legality and regularity of spending under the Common Agricultural Policy at Member State level. The Common Agricultural Policy accounts for almost 40 per cent of the EU Budget. We assessed whether a new framework set up in 2015 by the European Commission enables the Certification Bodies to form their opinions in line with EU regulations and international audit standards. Although the framework is a positive step towards a single audit model, we found that it is affected by significant weaknesses. We make a number of recommendations for improvement, to be included in new Commission guidelines due into force from 2018.

Executive summary

IWith a budget of 363 billion euro (in 2011 prices) for the 2014-2020 period (around 38 % of the total amount of the multiannual financial framework 2014-2020), the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) is under shared management between the Commission and the Member States (MSs). While the Commission delegates the implementation of the budget to paying agencies (PAs) designated by MSs, it retains ultimate responsibility and is required to ensure that the EU’s financial interests are protected as though the Commission were performing the delegated budget implementation tasks itself.

IIFor this purpose, certification bodies (CBs) appointed by MSs have been entrusted with the role of being the PAs’ independent auditors since 1996. They have been required, since the 2015 financial year, to also provide an opinion, prepared in accordance with internationally accepted audit standards, stating whether the expenditure for which reimbursement has been requested from the Commission is legal and regular. The 2015 financial year was thus the first for which the Commission could use the CBs’ enhanced work on legality and regularity.

IIIIn this context, we assessed whether the framework set up by the Commission enabled the CBs to draw an opinion on the legality and regularity of CAP expenditure in accordance with the applicable EU regulations and internationally accepted audit standards, thus providing reliable results for Commission’s assurance model. We conclude that the framework designed by the Commission for the first year of implementation of the new work of the CBs has significant weaknesses. As a result, the CBs’ opinions do not fully comply with the applicable standards and rules in important areas.

IVThe CBs’ new role is a positive step towards a single audit model because the CBs’ outputs have the potential to help MSs to strengthen their control systems, reduce audit and control costs and enable the Commission to obtain independent additional assurance as to the legality and regularity of expenditure.

VAgainst this backdrop, we analysed the Commission’s existing assurance model and the changes introduced to take account of the CBs’ enhanced role. We noted that the Commission’s assurance model remains based on the Member States’ control results. For the 2015 financial year, the CBs’ opinion on legality and regularity were merely one factor taken into account when the Commission calculated its adjustments of the errors reported in the Member States control statistics. As those opinions are the only source which provides independent assurance on legality and regularity on an annual basis, the CBs’ work, once done in a reliable manner, should become the key element for the Commission’s assurance.

VIOur examination of the Commission’s guidelines compliance with the applicable regulations and internationally accepted audit standards identified the following weaknesses:

- For the risk assessment procedure, we observed that the Commission required CBs to use the accreditation matrix which creates the risk of inflating the level of assurance that the CBs can derive from PAs’ internal control systems;

- The CBs’ sampling method for transactions based on the PAs’ lists of randomly selected on-the-spot checks entailed a series of additional risks that were not overcome: in particular, the CBs’ work can only be representative if the samples initially selected by the PAs are themselves representative. A portion of the sampling for non-IACS transactions is not representative of expenditure and is thus is not representative of the financial year audited;

- As regards substantive testing, the Commission required CBs, for part of the sampling, to carry out only a re-performance of the PAs’ administrative checks;

- The Commission required CBs for their substantive testing, only to re-perform the PAs’ initial checks. While re-performance is a valid audit collection method, internationally accepted audit standards also state that auditors should choose and perform all audit steps and procedures that they themselves consider appropriate in order to obtain sufficient audit evidence to form a reasonable assurance opinion;

- As regards the drawing of the auditor’s conclusion, we found that the guidelines required the CBs to calculate two different error rates in relation to legality and regularity, and that the use made of these rates not only by the CBs, but also by DG AGRI, was not appropriate;

- Finally, we concluded that the CBs’ opinion on the legality and regularity of expenditure was based on an understated total error. Indeed, the errors detected and reported by the PAs in their control statistics were not taken into account by the CBs in calculating their estimated level of error.

We make a number of recommendations to address these observations:

- The Commission should use the CBs’ results, when the work is defined and performed in accordance with the applicable regulations and internationally accepted audit standards, as the key elementof its assurance model regarding the legality and regularity of expenditure;

The Commission should revise its guidelines as follows:

- focus the CBs’ risk assessment as regards legality and regularity on the key and ancillary controls already used by the Commission;

- require CBs, for the selection by the CBs of IACS transactions from the list of claims randomly selected by the PAs for on-the-spot checks, to put in place appropriate safeguards concerning the representativeness of the CBs’ samples; the timely CBs on-the-spot visits; the non-disclosure of the CBs’ sample to the PAs;

- for the sampling of non-IACS expenditure, require the CBs to draw their samples directly from the lists of payments;

- allow the CBs to carry out: on-the-spot testing for any transaction audited, and to carry out all audit steps and procedures that they themselves consider appropriate, without being limited to re-performing the PAs initial checks;

- require the CBs to calculate only a single error rate regarding legality and regularity;

- for IACS transactions which are sampled from the list of PAs’ random on-the-spot checks, the overall error calculated by the CBs, to be able to issue an opinion on legality and regularity of expenditure, should also include the level of error reported by the PAs in the control statistics, extrapolated to the remaining transactions not subject to PA on-the-spot checks.The CBs have to ensure that the control statistics compiled by the PAs are complete and accurate.

Introduction

Expenditure under the Common Agricultural Policy

01For agriculture, EU support is granted through the European Agricultural Guarantee Fund (EAGF) and the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD). The total allocation for these two funds amounts to 363 billion euro (in 2011 prices) for the 2014-2020 programme period, which represents around 38 % of the total MFF for the period 2014-20201.

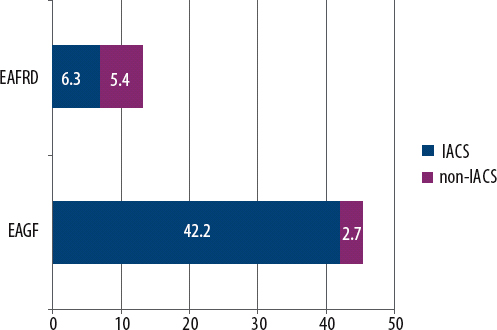

02Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) expenditure under both funds can be grouped in two categories:

- Integrated Administrative and Control System (IACS) expenditure, which is entitlement-based2 and consists mainly of annual per hectare payments.;

- non-IACS expenditure, which are reimbursement-based payments, consisting mainly of investments in farms and rural infrastructure, as well as interventions in agricultural markets.

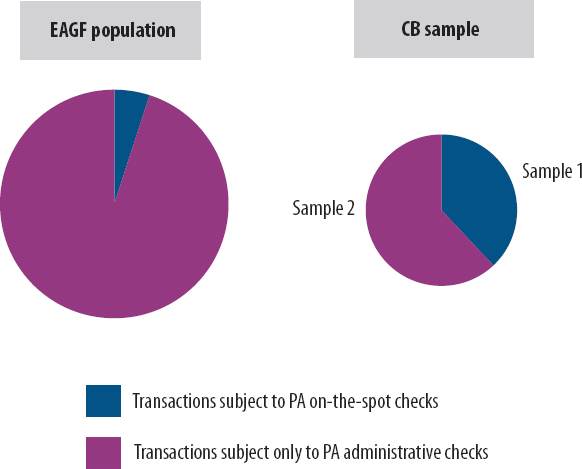

The split between IACS and non-IACS expenditure for the two funds (around 86 % and 14 % of CAP expenditure respectively) for the 2015 financial year is show in Figure 1 below:

Figure 1

The breakdown of CAP expenditure for the 2015 financial year (in billion euro)

The legal and institutional framework for shared management under the CAP

04Responsibility for managing the CAP is shared between the Commission and the Member States. About 99 % of the CAP budget is spent under shared management, as defined in the Financial Regulation3. The CAP Horizontal Regulation4 lays down ground rules specifically for the financing, management and monitoring of the CAP. The Commission has been empowered to further specify these rules through implementing regulations5 and guidelines.

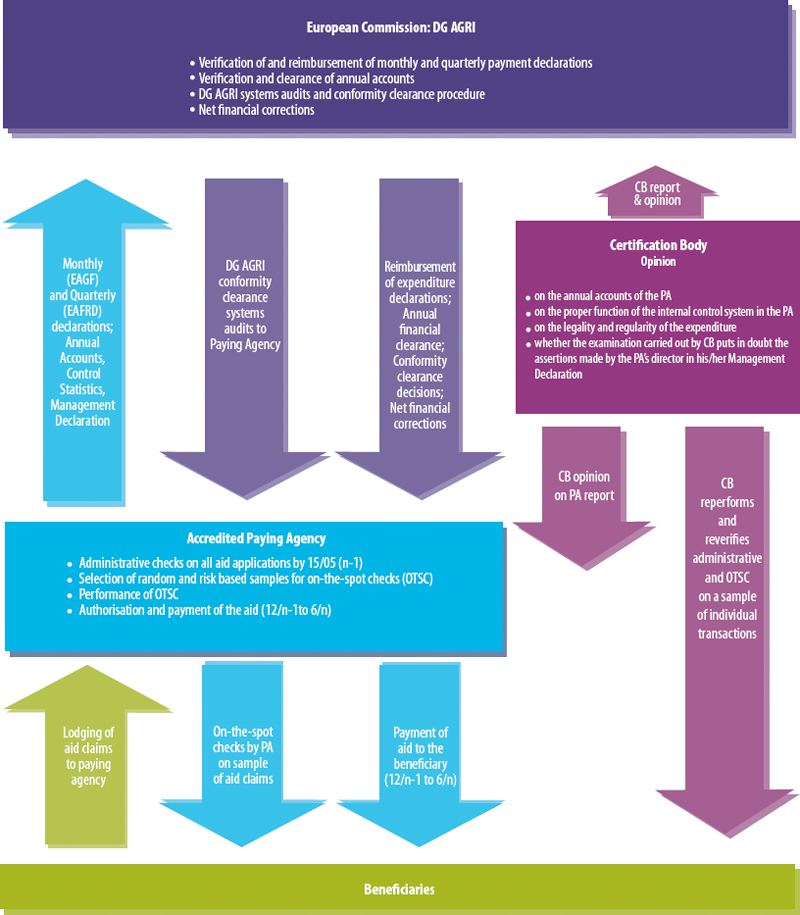

05Under shared management, the Commission remains ultimately responsible for the budget, but delegates its implementation to bodies specially designated by the Member States: the paying agencies (PAs). The Commission’s Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development (DG AGRI) oversees the PAs’ implementation of the budget, verifying and reimbursing the expenditure declared monthly (for the EAGF) and quarterly (for the EAFRD) by the PAs and, ultimately, assessing whether expenditure is legal and regular by means of the conformity clearance procedure6. If this procedure reveals weaknesses in a PA’s control system which have a financial impact on the EU budget, the Commission may apply financial corrections to that PA. DG AGRI’s shared management model, setting out the roles of the different parties involved, is presented in Annex I7.

06At Member State level, the CAP budget is managed by PAs accredited by the relevant Member State’s competent authority (CA)8. The PAs perform administrative checks on all project applications and payment claims received from beneficiaries, as well as on-the-spot checks on a minimum sample of 5 % for the vast majority of supporting measures9. Following these checks, the PAs pay the beneficiaries the amounts due and declare those amounts monthly (EAGF)/quarterly (EAFRD) to the Commission for reimbursement. All the amounts paid are then recorded in the PAs’ annual accounts. The director of each PA provides the Commission with these annual accounts, along with their declaration (the management declaration (MD)) regarding the effectiveness of their control systems, which also summarises the levels of error stemming from their control statistics10. The Commission’s authorising officer (DG AGRI’s Director General for the CAP) takes these annual accounts and MDs into account in DG AGRI’s annual activity report (AAR).

07The Financial Regulation requires the Commission, in entrusting the PAs with budget implementation tasks for the CAP under shared management, to ensure that the EU’s financial interests are protected to the same standard as though the Commission were performing these tasks itself11. This includes establishing appropriate control and audit responsibilities, such as the examination and acceptance of accounts. For the CAP, the certification body (CB) assumes these audit responsibilities at Member State level.

Role and responsibilities of certification bodies

08The CBs have been performing their role as independent auditors of the PAs since the 1996 financial year12. The role required the CBs to issue a certificate, in accordance with internationally accepted audit standards, stating whether the accounts to be transmitted to the Commission were true, complete and accurate, and whether the internal control procedures had operated satisfactorily, with particular reference to the accreditation criteria.

09The Financial Regulation13 and the CAP Horizontal Regulation14 have increased the role and responsibilities of CBs. In addition to their responsibility for the accounts and internal control, CBs have been required, since the 2015 financial year, to provide an opinion stating whether the expenditure for which reimbursement has been requested from the Commission is legal and regular. This opinion, drawn up in accordance with internationally accepted audit standards, must also state ‘whether the examination puts in doubt the assertions made in the MD’.

10The CAP horizontal regulation also stipulates that a CB must be a public or private audit body designated by the CA and that it must have the necessary technical expertise and be operationally independent from the PA, as well as from the authority which has accredited that PA. For the 2015 financial year, CAP expenditure in the 28 Member States was administered by a total of 80 PAs, which were in turn audited by 64 CBs15. Forty six of these CBs were public bodies16 and 18 were private audit companies.

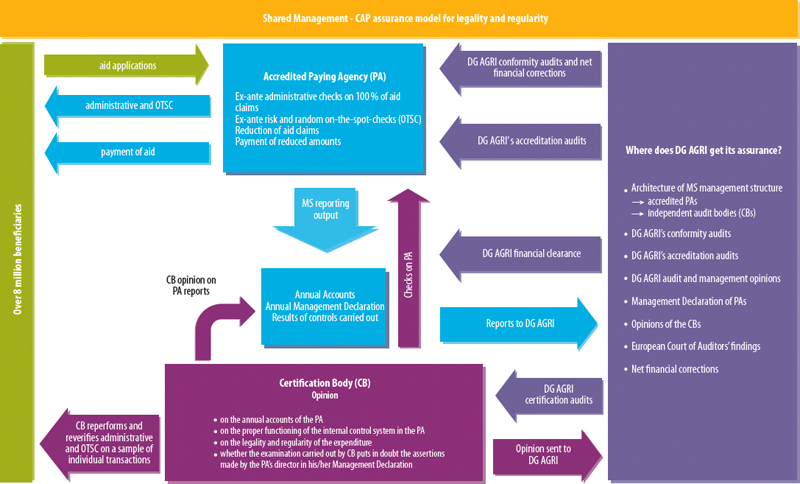

11The aim of the CBs’ work on legality and regularity is to increase DG AGRI’s assurance on the legality and regularity of expenditure. The CBs’ role in DG AGRI’s assurance model is described in Annex II. Possible uses of the CBs’ work in the context of a ‘single audit model’ are detailed in paragraphs 24 to 28.

12The Commission established the framework for the CBs’ audit work through an implementing regulation17 and additional guidelines18. According to this regulation, and in order to obtain reliable reports and opinions from the CBs, the Commission needs to ensure that:

- its guidelines provide appropriate instructions in accordance with internationally accepted audit standards19;

- the work carried out by the CBs based on such guidance is sufficient and of appropriate quality.

Audit scope and approach

Audit scope

13The new requirement for CBs to provide an opinion on the legality and regularity of the expenditure plays a key role in the Commission’s assurance model for the 2014-2020 period.

14In this audit, we focused our analysis on the framework established by the Commission for the CBs’ work on legality and regularity for the first year of implementation (2015 financial year). This audit did not assess the substantive testing carried out by the CBs.

15The audit aimed at assessing whether the CBs’ new role was a step towards a single audit approach and if the Commission took due account of it in its assurance model. The audit also aimed at assessing whether the framework set up by the Commission enables the CBs to draw an opinion on the legality and regularity of CAP expenditure in accordance with the applicable EU regulations and internationally accepted audit standards.

16In particular, we examined whether the Commission’s guidelines to CBs ensured:

- an appropriate risk assessment by the CBs and a representative sampling;

- an appropriate level of substantive testing; and

- a correct estimate of the level of error and audit opinion.

After the finalisation of our audit field work (September 2016), the Commission finalised in January 2017 new guidelines to be applied by CBs from 2018 financial year. These revised guidelines have not been subject to our review.

Audit approach

18The audit evidence was obtained at both Commission (DG AGRI) and Member State level. The starting point for the work was an analysis of the relevant legal framework, in order to identify the requirements applicable to all parties involved: the Commission, the CAs and the CBs.

19At Commission level, the audit involved:

- a review of the Commission’s guidelines for CBs applicable to the 2015 financial year, as well as documents from supporting activities such as expert group meetings20 (we participated as observers in one such meeting in Brussels on 14 and 15 June 2016);

- an assessment of the Commission’s desk reviews of CBs’ reports and opinions for 25 PAs in 17 Member States, which in 17 cases also included a review of DG AGRI’s reports on audit visits to CBs. We also reviewed DG AGRI’s 2015 AAR and the use made therein of CBs’ work on legality and regularity;

- interviews with relevant DG AGRI staff.

At Member State level, the audit involved:

- a survey of 20 CAs and CBs in 13 Member States21, selected based on the value of the expenditure they certified (in total, the selection accounted for 63 % of EU CAP expenditure in 2014) and on the CB’s legal status (i.e. whether it was a public or private entity). The topics covered by the surveys were amongst others the Commission’s guidance and support to the CBs;

- six visits22 to Member States, carrying out interviews with representatives from the CAs and CBs for the purpose of better understanding the information provided in the replies to the survey, as well as examining the CBs’ contractual arrangements, checking the timeliness of their audit procedures and reviewing the main results of their work as presented in their audit reports and opinions covering the 2015 financial year.

Our findings were examined against the relevant provisions in the regulations for the 2014-2020 programme period and the requirements laid down in the relevant International Standards of Supreme Audit Institutions (ISSAIs) or International Standards on Auditing (ISAs).

Observations

The CBs’ new role in relation to the legality and regularity of CAP expenditure is a positive step towards a single audit model

22While there is no single recognised definition of the term ‘single audit’, the concept is premised upon the need to avoid uncoordinated, overlapping controls and audits. In the context of the EU budget, and for shared management in particular, ‘single audit’ would provide assurance as to the legality and regularity of expenditure on two fronts: for management (internal control) purposes on the one hand and for audit purposes on the other. A single audit approach should be an effective control framework in which each layer builds on the assurance provided by others.

23In the area of Cohesion23, Member State audit authorities have been, since the 2007-2013 period, one of the main sources of information in the Commission’s assurance framework for the legality and regularity of expenditure. Also in our Opinion No 2/200424, we analysed the ‘single audit’ model for the purposes of internal control, i.e. as a source of assurance for the Commission’s management. Furthermore, in our Special Report No 16/201325, we made specific recommendations on improving the Commission’s procedures for using the work of national audit authorities in the area of Cohesion.

24For CAP expenditure, the Commission draws assurance that expenditure is legal and regular from three layers of information: the checks performed by the PAs, the audit work carried out by the CBs and the results of the Commission’s checks thereon. When such assurance is considered insufficient, the Commission exercises its ultimate responsibility for legality and regularity through its own conformity clearance procedures which may result in financial corrections.

25The CBs’ new role of issuing an opinion on the legality and regularity of expenditure has the potential, during the 2014-2020 period, to considerably strengthen a ‘single audit’ model for the Commission’s management of agricultural expenditure. According to DG AGRI, such a model will yield greater assurance that control systems are working well26 and that it will make it possible to derive additional management assurance from the audit work carried out by the CBs rather than from DG AGRI’s own checks27 alone.

26The CBs’ audit work can enable a ‘single audit’ model to operate efficiently for CAP expenditure:

- by helping Member States to strengthen their control systems;

- by helping to reduce audit and control costs;

- by enabling the Commission to obtain independent additional assurance as to the legality and regularity of expenditure.

We consider a ‘single audit’ approach is the right way to obtain assurance as to the legality and regularity of expenditure at Member State level. Under EU law, just as the European Court of Auditors acts as the external auditor for the EU budget as a whole, the CBs act as operationally independent auditors of agricultural spending at Member State/regional level. In chronological terms, they are the first auditors to provide assurance as to the legality and regularity of agricultural spending, and they are the only source of such assurance at national/regional28 level. CBs draw their assurance from a combination of their own substantive testing and the PAs’ control systems. In the context of a ‘single audit’ model for the 2014-2020 CAP, such assurance could potentially be used by the Commission, as indicated in Figure 2 below, provided an appropriate audit trail is ensured.

Figure 2

A single audit model for the CAP 2014-2020

Source: European Court of Auditors.

28We believe that the Commission, being ultimately responsible for the management of CAP funds and for the regulatory requirements in force, could make the following use of the CBs’ work on legality and regularity within the framework of a ‘single audit’ approach, when this work is reliable:

- improving how it estimates residual error and establishes reservations for its annual activity report29;

- determining whether or not the estimated level of error exceeds 50 000 euro or 2 % of the relevant expenditure30 and, hence, whether or not to start a conformity clearance procedure;

- determining more accurately and completely the amounts to be excluded from the EU budget, making more extensive use of extrapolated financial corrections31;

- assessing whether to ask MSs to review the accreditation status of PAs in cases where there are insufficient guarantees that payments are legal and regular32.

DG AGRI’s assurance model remains based on the Member States’ control results

29The Financial Regulation33 requires DG AGRI’s Director-General to prepare an AAR, declaring that he has reasonable assurance that the control procedures in place give the necessary guarantees concerning the legality and regularity of the underlying transactions.

30The assurance model used for this purpose by DG AGRI up until the 2015 financial year, which determined the amounts at risk from a legality and regularity perspective, took as its starting point the control statistics reported by Member States. Then top-ups were added on the basis of known weaknesses highlighted by DG AGRI’s conformity audits and also by our audit work. DG AGRI needed to increase the level of error where it found that part of the errors were not detected by the PAs and therefore not reflected in MSs’ control results. This calculation produced an adjusted error rate for each PA and each fund.

31The aggregated adjusted error rates for the 2014 and 2015 financial years show that DG AGRI continued to make adjustments on top of the levels of error reported in the PAs’ controls statistics (see Table 1). The information from the CB’s new opinions on legality and regularity had only a marginal effect on these adjustments for the 2015 financial year:

| Fund | Financial year | Average level of error reported in the PAs’ control statistics | Aggregated adjusted error rate calculated by DG AGRI |

|---|---|---|---|

| EAGF | 2014 | 0.55 % | 2.61 % |

| 2015 | 0.68 % | 1.47 % | |

| EAFRD | 2014 | 1.52 % | 5.09 % |

| 2015 | 1.78 % | 4.99 % |

In its 2015 AAR34 DG AGRI explained that it had made ‘very limited’ use of the CBs’ opinions on legality and regularity. This was mainly due to this being the first year in which the CBs had produced such opinions, the timing of their work, their lack of technical skills and legal expertise, their inadequate audit strategies and the insufficient sizes of the samples audited. In addition to the reasons indicated by DG AGRI, we consider that, based on our findings, the way the Commission defined the CBs’ work in its guidelines has also an important impact on the reliability of their work.

33In fact, DG AGRI’s assurance model remains based on the control results. For the 2015 financial year, the CBs’ opinions on legality and regularity were merely one factor taken into account when the Commission calculated its adjustments of the errors reported in the MSs’ control statistics. The CBs’ opinions on legality and regularity are the only source which provides an independent assurance on legality and regularity on an annual basis. Thus, once the CBs’ work is done in a reliable manner this independent assurance should in our view become the key element for the Commission’s Director-General for DG AGRI when assessing whether expenditure is legal and regular.

34The continuing focus on the control statistics stemming from the PAs management and control systems is confirmed by DG AGRI in its 2015 AAR which stated that ‘the opinion on legality and regularity should confirm the level of errors in the management and control system of the CAP that is operated in the Member States’35. DG AGRI stated further that ‘through testing of transactions (based on a statistical sample), the Certification Body auditors are requested to confirm the level of errors found in the initial eligibility checks performed by the Paying Agency and, if not confirmed, to give a qualified opinion’36.

35Some important aspects of the Commission’s guidelines, such as those listed below that we assess in this report, have thus been specifically put in place to accommodate DG AGRI’s existing assurance model based on the validation of the PAs’ control results:

- use of two samples, with Sample 1 drawn from the list of on-the-spot checks performed by the PAs (see paragraphs 48 to 58);

- limitation of the CBs’ on-the-spot testing to Sample 1 transactions (see paragraphs 62 to 67);

- limitation of the CBs’ scope to re-perform the PAs’ on-the-spot and administrative checks (see paragraphs 68 to 71);

- calculating two error rates and DG AGRI’s use of the ‘incompliance’ rate (IRR) instead of the error rate (ERR) (see paragraphs 72 to 78);

- understatement of the error rates based on which CBs express their opinions (see paragraphs 79 to 85).

Furthermore, in order to apply the Commission’s model, CBs need to perform a higher volume of work than what is strictly required by the CAP Horizontal Regulation. This is because the control statistics summarised in the PAs’ management declarations are calculated separately for the IACS and non-IACS strata (see paragraph 2). DG AGRI also calculates the adjusted error rates for each of the two strata. This means that CBs are also required to validate control statistics at strata level (IACS / non-IACS) and not only at fund level (EAGF/EAFRD). In order to have sufficient evidence to validate these statistics at strata level, CBs need to significantly increase the size of their samples compared to a scenario where only a validation at fund level is required.

37The next sections also examine the extent to which the Commission’s guidelines comply with internationally accepted audit standards at the different stages of the audit process (risk assessment and sampling method, substantive testing, conclusion and audit opinion).

Risk assessment and sampling method

Basing the risk assessment on the accreditation matrix may inflate the level of assurance the CBs can derive from PAs’ internal control systems

38As per DG AGRI’s guidelines37, the CBs obtain their overall level of assurance on legality and regularity from two sources: their assessment of the PAs’ control environment and their substantive testing of transactions. Such a model is in line with internationally accepted audit standards, which prescribe that the auditor should ‘understand the control environment and the relevant internal controls and consider whether they are likely to ensure compliance’38.

39The higher the CBs rate the PAs’ internal control systems, and hence the greater the assurance they derive from these systems, the fewer transactions will undergo substantive testing. Table 2 illustrates this inverse relationship using information from DG AGRI’s guidelines39:

| Internal control system rating | Works well | Works | Works partially | Does not work |

| Number of items included in substantive testing | 93 | 111 | 137 | 181 |

DG AGRI required the CBs to base their rating of the PAs’ internal control systems on a matrix for assessing the PAs’ compliance with the accreditation criteria (the ‘accreditation matrix’). Only accredited PAs (i.e. those fulfilling the accreditation criteria) may manage CAP expenditure40.

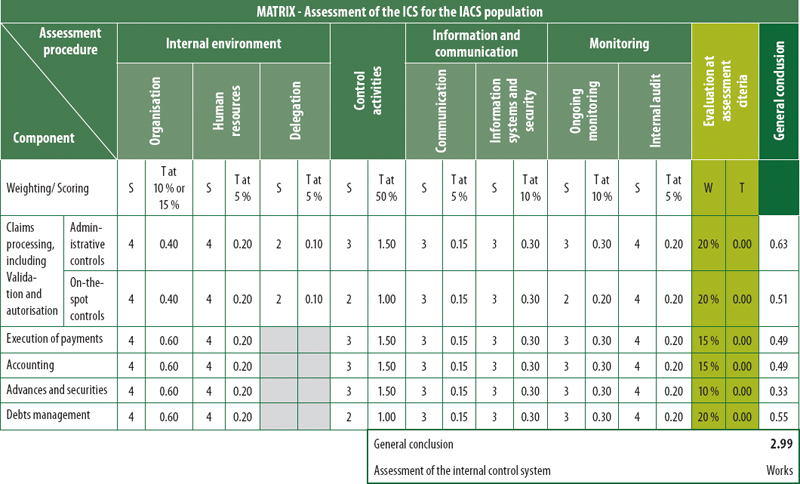

41As Annex III41 shows, the accreditation matrix consists of six functions and eight assessment criteria, making a total of 48 assessment parameters. Each individual parameter is given a score from one (‘Not working’) to four (‘Works well’) and a weighting. The overall score yielded by the accreditation matrix represents the weighted average of these 48 assessment parameters.

42This overall score is used both by the CAs (to assess whether PAs should keep their accreditation) and by the CBs (to help them form their opinion as to whether the PAs’ internal control systems are functioning properly).

43However, it is inappropriate to use the overall score yielded by the accreditation matrix to assess the PAs’ internal control systems in relation to legality and regularity of expenditure, as these depend mainly on only two of the 48 assessment parameters: administrative checks and on-the-spot checks on the processing of claims, including their validation and authorisation (under ‘Control activities’).

44Under the framework proposed by DG AGRI, low scores on these two parameters may be compensated for by higher scores on others (e.g. information and communication, monitoring). These other factors are not directly related to legality and regularity and should not, therefore, be used to compensate in this way. For legality and regularity purposes, given the overwhelming importance of these two parameters, such compensation may lead CBs to overrate internal control systems and derive more assurance from them than is warranted. Furthermore, this framework does not sufficiently take into account systemic weaknesses previously reported both by DG AGRI and by us following audits of PAs and final beneficiaries.

45In three42 of the six Member States visited, we found that the CBs had not taken sufficient account of known weaknesses in their systems assessments. Box 1 below presents the situation we found in one of these Member States (Germany (Bavaria)), along with the opposite situation found in Romania, where the CB actually made full use of such known weaknesses in its assessment. These situations support our view that the accreditation matrix is an inappropriate tool for assessing the functioning of internal control systems for legality and regularity.

Box 1

Situations where the accreditation matrix did not produce reliable results for legality and regularity purposes

In Germany (Bavaria), the accreditation matrix yielded a rating of ‘Works’ for the state’s EAFRD (non-IACS) internal control system. This rating was not consistent with the following evidence, which suggested that the control system for such expenditure was weaker:

- for the 2013 and 2014 financial years, DG AGRI had calculated that, in relation to the legality and regularity of expenditure, there was a material level of error, and

- the CB’s own verifications showed that a significant number of transactions contained financial errors (25 from the 2015 financial year, i.e. one third of the audited population).

In Romania, the accreditation matrix initially yielded a rating of ‘Works’ for the internal control systems for both funds (EAFRD and EAGF) and both strata (IACS and non-IACS). However, applying its professional judgement using the information available, including known weaknesses previously reported by DG AGRI and by us, the CB disregarded this outcome and reduced the corresponding ratings to ‘Does not work’ for EAGF (IACS) and ‘Works partially’ for EAFRD (IACS) and EAGF (non-IACS).

During its conformity clearance inquiries, DG AGRI uses key and ancillary controls (see Box 2 for definitions) to assess whether the internal control systems in place at Member State level are capable of ensuring the legality and regularity of expenditure.

Box 2

What are key and ancillary controls?43

‘Key controls shall be the administrative and on-the-spot checks necessary to determine the eligibility of the aid and the relevant application of reductions and penalties’.

‘Ancillary controls shall be all other administrative operations required to correctly process claims’.

Even though DG AGRI itself uses key and ancillary controls to assess whether PAs’ internal control systems ensure the legality and regularity of expenditure, it requires CBs to use a different tool for the same purpose: the accreditation matrix, which is not fit for that purpose.

The CBs’ sampling method for IACS transactions, based on the PAs’ lists of randomly selected on-the-spot checks, entaileds a series of risks that were not overcome

48As mentioned above the CAP Horizontal Regulation requires CBs to provide an opinion on the legality and regularity of the expenditure for which reimbursement has been requested from the Commission during the financial year being audited. Therefore, when designing an audit sample, the CBs ’shall consider the purpose of the audit procedure and the characteristics of the population from which the sample will be drawn’44.

49DG AGRI guidelines45 split the work for substantive testing into two samples:

- Sample 1: drawn by CBs from the list of beneficiaries randomly46 selected by the PAs for on-the-spot checks (see paragraph 6). For Sample 1 transactions, CBs are required to re-perform both the on-the-spot checks carried out by the PAs and the full range of administrative checks (receipt of the claim and eligibility checks, validation of expenditure, including the authorisation, execution and recording in the accounts of the corresponding payment).

- Sample 2: drawn by CBs from all payments for the year in question. For Sample 2, CBs need to re-perform only administrative checks, not on-the-spot checks (see paragraphs 62 to 67).

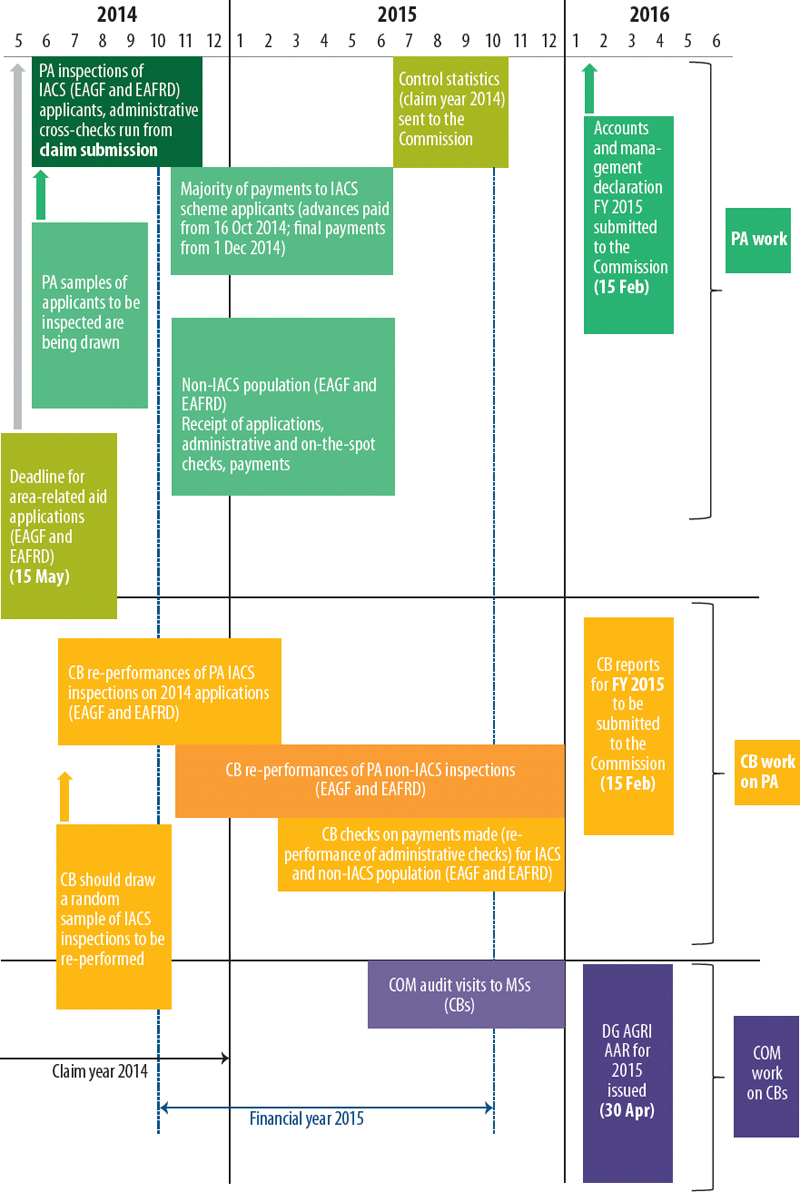

The timetable of the CBs substantive testing and reporting to the Commission are described in Annex IV.

51Sample 1 transactions are chosen from a list of randomly selected on-the-spot checks performed by the PA on claims, which, if they are IACS, are very likely to lead to payments during the corresponding financial year. Hence, the results of CBs’ testing not only serve the purpose of expressing an opinion on the legality and regularity of expenditure, but also help the CBs to form an opinion on the functioning of the PAs’ internal control systems, which is one of the other audit objectives laid down in the CAP Horizontal Regulation.

52The number of transactions upon which CBs re-perform all of the PA checks (see Table 3 below paragraph 64) is often considerably greater than the number of transactions usually required for compliance testing on internal control systems47. This gives them greater assurance that the PAs’ systems for administrative and on-the-spot checks comply with the applicable regulations.

53For audit results to be reliable, it is important that all samples used for substantive testing be representative. In order to be representative, samples must be drawn from the total population using statistically valid methods and remain unchanged. Because the CBs extract their samples in part from the PAs’ samples, the results of their work can only be representative if the PAs’ samples are themselves representative. Furthermore, any replacement of transactions contained in the initial samples must be appropriately justified and documented.

54DG AGRI requires CBs to assess the representativeness of the PAs’ samples. However, in order to comply with such a requirement, both the PAs and the CBs need to maintain a sufficient and reliable audit trail to confirm that the samples are representative, drawn from the entire population and have remained unchanged.

55DG AGRI requires Sample 1 IACS transactions for substantive testing to be selected based on the amounts claimed by farmers (claim-based selection) rather than the amounts they are actually paid48, so that the CBs can perform their re-verifications as soon as possible after the PAs’ on-the-spot checks. The advantage of the claim-based selection is that the conditions the CBs find when they inspect the selected farms on the spot will be very similar to those found by the PAs.

56However, for this method to work as intended, close cooperation and communication between the PAs and the CBs is important. The CBs need to be updated regularly on checks performed by the PA so that the CB can re-perform these checks shortly after the PA’s visit. We found that in three of the five Member States visited where the CB re-performed the IACS on-the-spot checks49, this condition was not met (see Box 3).

Box 3

Delays in the CBs’ re-performance of IACS Sample 1 on-the-spot checks for the 2014 claim year (2015 financial year)

In Poland, the CB completed the re-performance of 53 of the 60 EAGF IACS Sample 1 transactions after the end of the 2014 calendar year, with some being re-performed as late as March 2015. This was because the PA had been late in sending the CB the reports on its on-the-spot checks.

In Romania, the CB re-performed all six classical on-the-spot checks50 for EAFRD IACS Sample 1 transactions on average six months after the PA’s checks.

In Germany (Bavaria), up to three months had passed between the PA’s initial farm visits and the CB’s on-the-spot re-verifications for EAGF IACS transactions, and up to ten months for EAFRD IACS transactions.

Also, for this approach to be valid, the CBs need to have immediate access to the list of on-the-spot checks initially selected by the PAs, in order to ensure that this list is not subsequently changed. Moreover, a CB must not be allowed to exclude transactions from its sample as a result of delays in the PA’s decision granting the relevant aid. Allowing the CBs to exclude such transactions from the sample increases the risk of PAs intentionally delaying their decisions and payments for certain transactions, which might lead to errors in the CBs’ calculations. Such cases not only undermine the representativeness of the results and the validity of their extrapolation to overall expenditure, but may also cause an incorrect reduction in the error rate found by the CBs (see Box 4).

Box 4

Exclusion of transactions from IACS Sample 1 because the PA did not execute payment until after the CB had completed its audit work

In Romania, the CB excluded five transactions from its EAFRD IACS Sample 1 after completing its audit work because the PA had not yet executed the corresponding payments. Consequently, the CB did not take into consideration the results of the tests on these transactions in calculating the overall error rate upon which its opinion on the legality and regularity of transactions was based.

The application of the claim-based selection method also relies on the CBs not letting the PAs know which transactions they have selected until after the latter have already performed their checks, so that the PAs do not know which transactions the CBs will later scrutinise (the Commission has also recognised this risk in cases where CBs accompany the PAs on their initial checks)51. However, we found that in Italy such safeguards were not in place (see Box 5).

Box 5

The re-performance exercise was compromised in Italy because the CB had given the PA advance notice of which beneficiaries would be subject to re-performance

In Italy, for the 2015 claim year (2016 financial year), the CB gave the PA the list of transactions it had selected for Sample 1 IACS for both funds (EAGF and EAFRD) before the PA had carried out the majority of its initial on-the-spot checks. As a result, the PA already knew before starting its on-the-spot checks which transactions would subsequently be subject to re-performance by the CB.

If, when carrying out its on-the-spot checks, the PA knows which transactions are scheduled for re-performance by the CB at a later date, it is likely to scrutinise these transactions more closely. As a result, these checks will be more accurate than those not scheduled for re-performance, so the CB will find fewer errors.

Moreover, since the results for these transactions will be used to extrapolate the level of error for the entire population, these biased transactions will render the overall error rate unrepresentative and more than likely result in it being understated.

A portion of the non-IACS transactions upon which the CBs perform substantive testing is not representative of expenditure in the financial year audited

59For non-IACS transactions (both EAGF and EAFRD), there is a significant disparity between:

- the period for which the on-the-spot checks are reported, which is the calendar year (from 1 January to 31 December 2014 for the 2015 financial year, in this case), and

- the period for which expenditure is paid, which for the 2015 financial year is from 16 October 2014 to 15 October 2015.

As a result, some of the beneficiaries subject to on-the-spot checks performed during the 2014 calendar year were not reimbursed in the 2015 financial year52. The CBs cannot use the results of such transactions in their calculation of the error rate for the financial year concerned. Such results may only be used to express an opinion on the functioning of the internal control system and provide a statement on the assertions in the MD and its underlying control statistics.

61As a result, the number of transactions the CBs use in calculating the overall error rate is lower, thus reducing its accuracy and, in turn, affecting the reliability of their opinions on the legality and regularity of expenditure for the financial year.

Substantive testing

For most transactions, the guidelines do not require the CBs to perform on-the-spot testing at final beneficiary level

62According to internationally accepted audit standards, ‘in performing a reasonable assurance audit, public sector auditors gather sufficient appropriate audit evidence to provide a basis for the auditors’ conclusions’53. They should use a variety of techniques for this purpose, such as observation, inspection, inquiry, re-performance, confirmation and analytical procedures. Furthermore, under EU law, the CBs’ substantive testing of expenditure must cover verifying the legality and regularity of the underlying transactions at final beneficiary level54.

63Inspection involves examining books, records and other elements (such as the beneficiaries’ right of use for the land in question, fertilisation registers, building permits, etc.) or physical assets (such as land, animals, equipment, etc.). Inquiry involves obtaining information and explanations from final beneficiaries, in the form of either written statements or more informal oral discussions.

64As mentioned above, for sample 2, the Commission’s guidelines only require CBs to re-perform administrative checks (see paragraph 49). In Table 3, we calculated the proportion of Sample 2 transactions in the total sample for the six Member States visited.

| Member State | EAGF | EAFRD | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample 1 | Sample 2 | Total sample | % of Sample 2 in total | Sample 1 | Sample 2 | Total sample | % of Sample 2 in total | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) = (1)+(2) | (4) = (2)/(3)*100 | (5) | (6) | (7) = (5)+(6) | (8) = (6)/(7)*100 | |

| Germany (Bavaria) | 30 | 41 | 71 | 58 % | 60 | 146 | 206 | 71 % |

| Spain (Castilla y Léon) | 52 | 123 | 175 | 70 % | 50 | 122 | 172 | 71 % |

| Italy (AGEA1) | 30 | 192 | 222 | 86 % | 30 | 91 | 121 | 75 % |

| Poland | 90 | 58 | 148 | 39 % | 97 | 33 | 130 | 25 % |

| Romania | 161 | 292 | 453 | 64 % | 140 | 245 | 385 | 64 % |

| United Kingdom (England) | 30 | 40 | 70 | 57 % | 59 | 26 | 85 | 31 % |

| Average proportion of Sample 2 in the Member States/Regions visited (with no on-the-spot testing) | 62 % | 56 % | ||||||

1 The ‘Agenzia per le erogazioni in agricoltura’ (AGEA) is one of the 11 Italian PAs.

65As the table above shows, in four of the Member States/Regions visited, Sample 2, for which no on-the-spot testing is done, accounted for the majority of the overall sample used by CBs for substantive testing.

66For sample 2, gathering evidence based only on a re-performance of administrative checks at PA level, will often not provide the CBs with sufficient and appropriate audit evidence as required by ISSAI 4200. By doing so, the CBs are not using two audit collection methods that are very important in the context of the CAP expenditure: inspection and inquiry. Without these methods, important audit evidence cannot be collected, such as evidence that farmers are using their land as stated in their declarations and proof of the existence of physical assets purchased through investment projects. This approach therefore falls short of internationally accepted audit standards.

67Without sufficient on-the-spot testing, the CBs may not be able to obtain reasonable assurance that the relevant expenditure is legal and regular: as we have demonstrated in our annual reports, most of the errors in CAP expenditure (particularly for IACS) are found on the spot55.

The guidelines require the CBs only to re-perform PAs’ initial checks, rather than carry out all the audit procedures the CBs consider necessary to obtain reasonable assurance

68‘The nature, timing and extent of procedures performed […] are determined by public sector auditors applying professional judgement’56. With regards to the standards applicable when performing the reasonable assurance audit see also paragraph 62.

69DG AGRI required CBs, for their substantive testing, only to re-perform (re-verify) the PAs’ initial checks, for both Sample 1 and Sample 2 transactions57. For example, if the initial on-the-spot checks had been done by the PAs using remote sensing58, then the CBs were always required to re-perform them using the same method59.

70Re-performance is defined by internationally accepted audit standards60 as ‘independently carrying out the same procedures already performed by the audited entity’, in this case the PA. For example, CBs may re-perform administrative checks to test whether the PAs made the correct decisions when granting aid.

71While re-performance is a valid audit evidence collection method, the Commission should not, in our opinion, require the CBs to limit themselves to such method for all transactions subject to substantive testing but instead leave it up to the CBs to determine the extent of its use. CBs might choose and perform audit steps and procedures that they themselves consider appropriate, which should not be limited to re-performance. Substantive testing based only on re-performance might not allow the CBs to obtain sufficient audit evidence to form a reasonable assurance opinion.

Conclusion and audit opinion

The guidelines require the CBs to calculate two different error rates and the use made of these rates by the CBs and DG AGRI is not appropriate

72In order to comply with DG AGRI guidelines61, CBs must calculate two error rates for legality and regularity purposes (see Table 4):

| Characteristics | Error rate (ERR) | ‘Incompliance’ rate (IRR) |

|---|---|---|

| Use made by the CB | To express an opinion on the completeness, accuracy and veracity of the PA’s annual accounts, on the proper functioning of its internal control system and on the legality and regularity of the expenditure for which reimbursement has been requested from the Commission. | To assess whether their examination puts in doubt the assertions made in the MDs, including the errors reported by PAs in the control statistics. |

| Population to which the rate refers to | Expenditure for the financial year (e.g. 16 October 2014 to 15 October 2015). | Controls performed by the PA during the calendar year (e.g. 1 January 2014 to 31 December 2014). |

| PA procedures taken into account | The entire control process performed by the PA, from receipt of claims until payment and accounting. | Only PA’s primary eligibility controls (administrative and on-the-spot checks), before sanctions are applied. |

| Errors taken into account | Only overpayments by the PA are taken into account. | It takes into account both the over- and under-validations by the PA. |

Article 9 of the CAP Horizontal Regulation requires the CBs to express a ‘limited’ (negative) assurance conclusion62 in relation to the MD. Such a conclusion does not require fully-fledged audit work, but merely a review, usually limited to analytical procedures and enquiries. Tests of details, such as substantive testing of transactions, are not required. A limited assurance review therefore provides a lower level of assurance than a reasonable assurance audit. The limited assurance conclusion is usually worded as follows: ‘nothing has come to our attention that would indicate that the subject matter is not in compliance, in all material respects, with the stated criteria’.

74Thus, in order to be compliant with internationally accepted audit standards, the conclusion on the MD can be drawn from the results of the audit work done in relation to the reliability of accounts, the proper functioning of the internal control system and the legality and regularity of transactions (including the ERR), i.e. as a ‘by-product’ of this work. However, DG AGRI guidelines additionally require the CBs to calculate the IRR in order to draw a conclusion on the MDs.

75Furthermore, in its 2015 annual activity report63, DG AGRI explained that, in principle, it intended to use the IRR to estimate an adjusted error rate for legality and regularity purposes. So, whereas the CBs’ opinions on the legality and regularity of expenditure are based on the ERR, DG AGRI‘s assurance model uses a different indicator of error, the IRR, in order to estimate the amounts at risk from a legality and regularity perspective.

76The IRR does not represent the level of error in the expenditure, but rather the financial impact of weaknesses in the PA’s administrative and on-the-spot checks.

77DG AGRI’s guidelines require the CBs to use the ERR calculated for legality and regularity purposes to also form an opinion on the completeness, accuracy and veracity of the PAs’ annual accounts (see Table 4). In its annual review of the PAs’ accounts (the ‘financial clearance procedure’), DG AGRI itself also uses the error rate for legality and regularity in order to assess the reliability of the PAs’ accounts.

78However, this is contrary to the CAP Horizontal Regulation64 which, for the financial clearance procedure, clearly separates the issue of the reliability of the PAs’ accounts from that of the legality and regularity of expenditure. This distinction is appropriate because, for example, a payment may be properly accounted for despite not being legal and regular (e.g. because a farmer claimed aid for land worked by another farmer); and, vice-versa, a payment may be legal and regular despite being incorrectly accounted for (e.g. recorded as reimbursement of an investment project instead of as annual area-based payment). Given this separation, DG AGRI’s use of the ERR to assess the reliability of the PAs’ accounts is inappropriate.

The CBs’ opinion on the legality and regularity of expenditure is based on an understated total error

79The two indicators of error (ERR and IRR) are calculated as the difference between what the CB considers eligible and what the PA has previously validated. The differences between what beneficiaries claimed and what the PA validated after its on-the-spot checks, which constitute the errors reported by the PAs in the control statistics, are not taken into consideration in the CBs’ ERR.

80As paragraph 6 states, as a general rule, only 5 % of claims are subject to on-the-spot checks by the PAs. And yet, for the six Member States visited, the average share of transactions subject to PA on-the-spot checks in the overall sample audited by CBs (see Table 3) is 38 % for EAGF and 44 % for EAFRD. Hence, such transactions are overrepresented in the overall CB samples. Figure 3 below illustrates this situation with the average figures for the EAGF fund.

Figure 3

The proportion of transactions subject to PA on-the-spot checks in the EAGF population and in the average CB sample

Source: European Court of Auditors.

81Where transactions have previously been subject to on-the-spot checks, the PA has already detected and reported errors for these in the control statistics. These errors will no longer be identified by the CBs when comparing their results to the PAs’ results. However, potential errors will remain uncorrected for the 95 % of the population not subject to on-the-spot checks.

82Thus, the CBs must accurately reflect the proportion of Sample 1 transactions that have previously been subject to on-the-spot checks ensuring a true representation of the characteristics of the total population. Therefore, they need to add to their own error rate the PA’s error rate, from the control statistics, for its random on-the-spot checks on the share of Sample 1 transactions in excess of 5 %65 that have previously undergone such checks.

83The PA’s error rate from the control statistics likewise needs to be added to the CB’s error rate for those Sample 2 transactions which have not been subject to any on-the-spot checks, either by the PA66 or by the CB.

84This adjustment is needed because CBs are required to express an opinion on the legality and regularity of the entire population of payments, and not only on the effectiveness of the PAs’ procedures for on-the-spot checks. In the absence of such adjustments, the ERR is likely to be significantly understated for both Sample 1 and Sample 2.

85In addition to the lack of such adjustments, the weaknesses reported in paragraphs 56, 57, 58, 67 and 71 of this report are also likely to result in the error rate used by CBs for their opinion on legality and regularity being understated.

Conclusions and recommendations

86With a budget of 363 billion euro (in 2011 prices) for the 2014-2020 programme period, CAP expenditure is under shared management between the Commission and the Member States. While the Commission delegates the implementation of the budget to PAs designated by Member States, it retains ultimate responsibility and is required to ensure that the EU’s financial interests are protected to the same standard as though the Commission were performing the delegated budget implementation tasks itself.

87The Commission draws assurance that expenditure is legal and regular from three layers of information: the checks performed by the PAs, the audit work carried out by the CBs and the results of the Commission’s checks thereon. When such assurance is considered insufficient, the Commission exercises its ultimate responsibility for legality and regularity through its own conformity clearance procedures which may result in financial corrections.

88The CBs have been entrusted with their role as the PAs’ independent auditors since 1996. While they were initially responsible for issuing a certificate on the reliability of accounts and on internal control procedures, their responsibilities were increased for the 2014-2020 period. CBs have been required, since the 2015 financial year, to also provide an opinion, drawn in accordance with internationally accepted audit standards, stating whether the expenditure for which reimbursement has been requested from the Commission is legal and regular. The 2015 financial year, then, was the first for which the Commission could use the CBs’ enhanced work on legality and regularity in preparing its AAR.

89In this context, the present report assessed whether the CBs’ new role was a step towards a single audit model and if the Commission took due account of it in its assurance model. We also assessed whether the framework set up by the Commission enabled the CBs to draw an opinion on the legality and regularity of CAP expenditure in accordance with the applicable EU regulations and internationally accepted audit standards.

90We conclude that although the CBs’ new role is a positive step towards a single audit model, the Commission could take very limited assurance from the CBs’ work on legality and regularity.In addition, we conclude that the framework designed by the Commission for the first year of implementation of the new work of the CBs has significant weaknesses. As a result, the CBs’ opinions do not fully comply with the applicable standards and rules in important areas.

91We consider the CBs’ new role in relation to the legality and regularity of expenditure to be a positive step towards a single audit model, in which the different layers of control and audit can be complementary, thus avoiding uncoordinated, overlapping controls and audits. This is because the CBs’ outputs have the potential to help Member States to strengthen their control systems, reduce audit and control costs and enable the Commission to obtain independent additional assurance as to the legality and regularity of expenditure. Furthermore, the CB’s work on legality and regularity can also help the Commission in improving how it estimates the overall residual error, assessing the need for conformity audits, determining more accurately and completely the amounts to be excluded from the EU budget, making more extensive use of extrapolated financial corrections and reviewing the accreditation status of PAs (paragraphs 22 to 28).

92Against this backdrop, we analysed the Commission’s existing assurance model and the changes introduced to take account of the CBs’ enhanced role. We noted that the Commission’s assurance model remains based on the Member States’ controls results. For the 2015 financial year, the CBs’ opinions on legality and regularity were merely one factor to be taken into account when the Commission calculated its adjustments of the errors reported in the Member States’ control statistics. For the financial years 2014 and 2015, the Commission made top-ups which increased the overall residual error by between two to four times what was reported by Member States. The CBs’ opinions on legality and regularity are the only source which provides independent assurance on legality and regularity on an annual basis. Thus, once the CBs’ work is done in a reliable manner this independent assurance should in our view become the key element for the Commission’s Director-General for DG AGRI when assessing whether expenditure is legal and regular (paragraphs 29 to 36).

Recommendation 1 - Assurance from the CBs’ work on legality and regularity

The Commission should use the CBs’ results, when the work is defined and performed in accordance with the applicable regulations and internationally accepted audit standards, as the key element of its assurance model regarding the legality and regularity of expenditure.

93We then examined the extent to which the Commission’s guidelines complied with the applicable regulations and internationally accepted audit standards at the different stages of the audit process. For the risk assessment procedure, we observed that the Commission required CBs to use the accreditation matrix in order to determine the extent to which they should rely on the PAs’ internal control systems. The accreditation matrix is used by CBs to assess the PAs’ compliance with accreditation criteria and contains 48 assessment parameters, out of which only two have a significant impact on the legality and regularity of expenditure: the administrative and the on-the-spot checks on the processing of claims.

94Thus, it is inappropriate to use this matrix for legality and regularity purposes, because this may increase the level of assurance the CBs derive from PAs’ internal control systems and decrease the size of their samples for substantive testing. During its conformity clearance inquiries, the Commission uses a different tool to assess the effectiveness of the PAs internal control systems: a list of key and ancillary controls, which comprise the administrative checks and physical on-the-spot checks, as well as other administrative operations, required to ensure the correct calculation of the amounts to be paid (paragraphs 38 to 47).

Recommendation 2 – Risk assessment focused on key and ancillary controls

The Commission should revise its guidelines so that the CBs’ risk assessment as regards legality and regularity is focused on the key and ancillary controls already used by the Commission, complemented by any other evidence that the CBs judge appropriate in accordance with internationally accepted audit standards.

95For the sampling of transactions, the Commission required CBs to use two samples whose results are then merged: Sample 1, drawn from the list of beneficiaries randomly selected by the PAs for on-the-spot checks, and Sample 2, drawn from all payments for the financial year in question. This approach allows the CBs to test a significant number of transactions (Sample 1) which have also been verified on-the-spot by the PAs, so that the CBs gather evidence regarding the functioning of the PAs internal control system and the reliability of the PAs control statistics where the results of the PAs on-the-spot checks are reported. However, because the CBs extract Sample 1 from the PAs’ random on-the-spot checks, their work can only be representative if the samples initially selected by the PAs are themselves representative.

96Furthermore, for IACS transactions, which are mainly annual area-based payments, Sample 1 was selected based on the amounts claimed by farmers, before the PAs had determined the amounts to be paid. The Commission chose this solution so that the CBs could perform their re-verifications as soon as possible after the PAs’ checks, when the conditions the CBs found when inspecting the selected farms on-the-spot would be very similar to those found by the PAs. However, this solution entails several risks, such as: insufficient cooperation between the PAs and CBs which significantly delays the timing of the CBs testing, the risk of transactions potentially affected by error being replaced in the CB sample or the risk of the CBs announcing their visit before the PAs carry out their initial checks (paragraphs 48 to 58).

Recommendation 3 – Safeguards for IACS sampling based on PAs’ on-the-spot checks

For the selection by the CBs of IACS transactions from the list of claims randomly selected by the PAs for on-the-spot checks, the Commission should reinforce its guidelines, requiring CBs to put in place appropriate safeguards that:

- ensure that the CBs’ samples are representative, are transmitted upon request to the Commission and that an appropriate audit trail is maintained. This means that the CBs need to check whether the Pas’ samples are representative;

- enable the CBs to plan and carry out their visits shortly after the PAs have carried out their on-the-spot checks;

- ensure that CBs do not disclose their sample to the PAs before the latter carried out their on-the-spot checks.

For non-IACS expenditure, which is mainly reimbursement-based expenditure for investments in farms and rural infrastructure, there is a disparity between the period for which PAs’ on-the-spot checks are reported (e.g. from 1 January to 31 December 2014 for the 2015 financial year) and the period for which expenditure is made (e.g. from 16 October 2014 to 15 October 2015 for the 2015 financial year). This means that those payments executed before 16 October 2014 or after 15 October 2015 will not represent expenditure for the 2015 financial year (paragraphs 59 to 61).

Recommendation 4 – Non-IACS sampling based on payments

The Commission should revise its guidelines with regards to the sampling method for non-IACS expenditure, so that the CBs sample non-IACS expenditure directly from the list of payments executed during the financial year being audited.

98For Sample 2, the Commission required CBs to carry out only a re-performance of the PAs’ administrative checks. In most Member States visited, Sample 2 accounted for the majority of the total CB sample used for substantive testing. However, gathering evidence based only on a documentary review at PA level, without any on-the-spot testing at final beneficiary level, will often not provide the CBs with sufficient and appropriate audit evidence as required by internationally accepted audit standards, as it deprives the auditor of two audit evidence collection methods that are very important in the context of the CAP expenditure: inspection and inquiry (paragraphs 62 to 67).

99The Commission required CBs, for their substantive testing, only to re-perform (re-verify) the PAs’ initial checks, for both Sample 1 and Sample 2 transactions. Re-performance is defined by internationally accepted audit standards as ‘independently carrying out the same procedures already performed by the audited entity’, in this case the PA. However, these standards state that auditors should choose and perform all audit steps and procedures that they themselves consider appropriate. As such, because the Commission limits the CBs to re-performance, their substantive testing is incomplete and does not provide them with sufficient audit evidence to form a reasonable assurance opinion (paragraphs 68 to 71).

Recommendation 5 – Substantive testing carried out on-the-spot

The Commission should revise its guidelines to allow the CBs to carry out:

- on-the-spot testing for any transaction audited;

- all audit steps and procedures that they themselves consider appropriate, without being limited to re-performing the PAs’ initial checks.

The Commission requires the CBs to calculate two indicators of error in relation to legality and regularity:

- the ERR, which is based on the CB’s audit of the PA’s entire control process, from receipt of claims until payment and accounting, and is used to express an opinion on the legality and regularity of expenditure; and

- the IRR, which measures only the financial impact of errors in the PA’s primary eligibility controls (administrative and on-the-spot checks) before sanctions are applied and is used to assess whether the CBs’ examination casts doubt on the assertions made in the MDs, including the levels of error reported by PAs in the control statistics.

However, the CAP Horizontal Regulation requires only limited assurance regarding the MDs, which is usually based on work that is limited to analytical procedures and enquiries, with no tests of details.

101The IRR is not necessary for ensuring compliance with internationally accepted audit standards, as the conclusion on the MDs can be drawn as from the results of the audit work done in relation to the reliability of accounts, the proper functioning of the internal control system and the legality and regularity of transactions. Furthermore, the Commission envisaged using the IRR instead of the ERR in the calculation of the adjusted error rate, despite the fact that the IRR does not represent the level of error in the expenditure but rather the financial impact of weaknesses in the PA’s administrative and on-the-spot checks. On the other hand, however, the ERR has been wrongly used by both the CBs and the Commission to form a view on the completeness, accuracy and veracity of the PAs’ accounts (paragraphs 72 to 78).

Recommendation 6 – A single error rate in relation to legality and regularity

The Commission should revise its guidelines so that they do not require the calculation of two different error rates regarding legality and regularity. A single error rate, based on which the CBs expressed their reasonable assurance opinion on legality and regularity of expenditure and limited assurance conclusion on the assertions made in the management declaration, would satisfy the requirements of the CAP Horizontal Regulation.

The Commission and the CBs should not use such an error rate for legality and regularity to judge the completeness, accuracy and veracity of the PA’s annual accounts.

102The ERR is calculated as the difference between what the CB considers eligible and what the PA has previously validated. The differences between what beneficiaries claimed and what the PA validated after its on-the-spot checks, which constitute the errors reported by the PAs in the control statistics, are not taken into consideration in the ERR which is the basis of the CBs’ opinion on legality and regularity of expenditure. Where transactions have previously been subject to on-the-spot checks, the PAs have already detected and reported the corresponding errors in their control statistics. These errors will no longer be identified by the CBs when comparing their results to the PAs’ results, and the CBs are therefore likely to find fewer errors for such transactions. Thus, the more transactions have previously been subject to PA checks in the CB sample, the lower the overall level of error found by the CBs will be.

103In the six Member States visited, the average share of transactions subject to PA on-the-spot checks in the overall sample audited by CBs was 38 % for EAGF and 44 % for EAFRD. However, as a general rule, the percentage of transactions in the total population subject to PA on-the-spot checks is only 5 %. Thus, in the CB samples, the transactions which had previously been subject to PA on-the-spot checks – and which were therefore less affected by error in CB testing –were overrepresented in the overall CB samples. This led to underestimated levels of error being reported by the CBs, because the CBs had not made any adjustments to ensure a faithful representation of the much smaller proportion of transactions previously subject to PA on-the-spot checks in the actual population (paragraphs 79 to 85).

Recommendation 7 – An error rate representative of the population covered by the audit opinion

The Commission should revise its guidelines so that:

- for IACS transactions which are sampled from the list of PAs’ random on-the-spot checks, the overall error calculated by the CBs also includes the level of error reported by the PAs in the control statistics, extrapolated to the remaining transactions not subject to PA on-the-spot checks.The CBs have to ensure that the control statistics compiled by the PAs are complete and accurate;

- for the transactions sampled by the CBs directly from the full population of payments, no such adjustment is necessary because the sample would be representative of the underlying populations audited.

The above recommendations 2 to 7 have as their implementation target the next revision of the Commission’s guidelines applicable from the financial year 2018 onwards. The Commission finalised in January 2017 new guidelines to be applied by CBs from 2018 financial year. These revised guidelines have not been subject to our review (see paragraph 17).

This Report was adopted by Chamber I, headed by Mr Phil WYNN OWEN, Member of the Court of Auditors, in Luxembourg at its meeting of 22 March 2017.

For the Court of Auditors

Klaus-Heiner LEHNE

President

Annexes

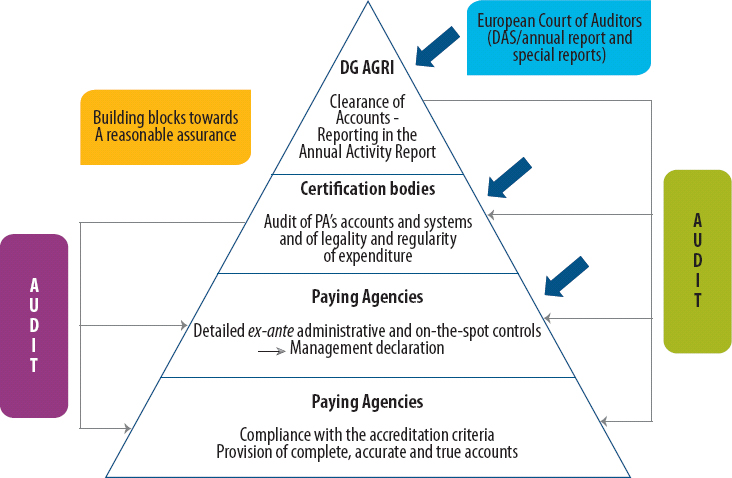

Annex I

The Commission’s shared management model, as presented in its 2015 AAR

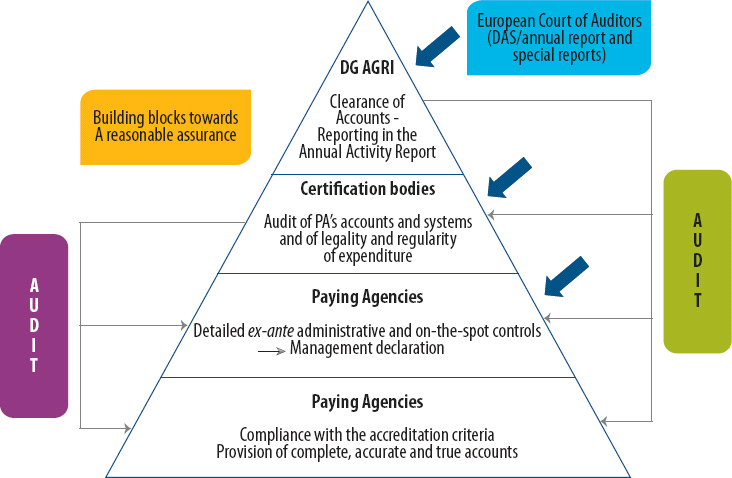

Annex II

The Commission’s assurance model for legality and regularity of expenditure, as presented in its 2015 AAR

Annex III

An example of an accreditation matrix, adapted from DG AGRI’s Guideline No 3 for the certification audit of the accounts

Annex IV

The timetable of the PAs’ and CBs’ substantive testing and reporting to the Commission

Glossary

Accreditation: A process to certify that paying agencies have an administrative organisation and internal control system which provide sufficient guarantees that payments are legal and regular, and properly accounted for. Such certification is to be made by MSs on the basis of the paying agencies’ compliance with a set of criteria (‘accreditation criteria’) regarding internal environment, control activities, information and communication, monitoring.

Adjusted error rate: This is the Commission’s estimate of the level of residual error affecting the CAP payments by PAs to beneficiaries after all checks have been carried out. The Commission calculates them and publishes them in its AAR.

Administrative checks: Formalised documentary checks carried out by PAs on all applications in order to verify that they comply with the terms under which aid is granted. For IACS expenditure, the information contained in IT databases is used for automatic cross-checks.

Annual Activity Report (AAR): An annual report published by every Directorate-General detailing its achievements, initiatives it has taken during the year and the resources it has used. DG AGRI’s annual activity report also includes an assessment of the functioning and the results of the CAP management and control systems at PA level.

Conformity clearance procedure: Commission’s procedure based on an assessment of the PAs’ internal control systems, to ensure that Member States apply EU and national law and that any expenditure that infringes these rules in one or more financial years is excluded from EU financing via a financial correction.

Control statistics: Annual reports submitted by Member States to the Commission that contain the results of the paying agencies’ administrative and on-the-spot checks.

European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD): Finances the Union’s financial contribution to rural development programmes.

European Agricultural Guarantee Fund (EAGF): Provides funding for direct payments to farmers, for the management of agricultural markets and for information and promotion measures.

Financial clearance procedure: Results in Commission’s annual financial decision concerning the completeness, accuracy and veracity of the annual accounts of each accredited PA.

Financial corrections: Commission’s exclusions from EU financing of expenditure that Member States have not effected in conformity with the applicable EU and national law. For CAP expenditure, the exclusions always take the form of financial corrections treated as assigned revenue.

Integrated Administration and Control System (IACS): An integrated system consisting of databases of holdings, applications, agricultural areas, animals and, where applicable, payment entitlements. These databases are used for administrative cross-checks on aid applications for area and animal related payments.

Internationally accepted audit standards (IAAS) comprise auditing standards specified by different public and professional standard-setting bodies, such as the International Standards on Auditing (ISAs) issued by the International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (IAASB) or the International Standards of Supreme Audit Institutions (ISSAI) issued by the International Organisation of Supreme Audit Institutions (INTOSAI).

Management declaration (MD): A yearly declaration of the Directors of each PA as to the completeness, accuracy and veracity of the accounts and the proper functioning of the internal control systems, as well as to the legality and regularity of the underlying transactions. Several annexes accompany the MD, among which one regarding the statistics of the results of all the administrative and on-the-spot checks performed by the PA (‘the control statistics’).

On-the-spot checks: Checks carried out by PAs’ inspectors in order to verify that the final beneficiaries comply with the applicable rules. These can take the form of classical on-the-spot visits (to agricultural holdings or investments subject to aid) or of remote sensing (review of recent satellite images of parcels) to be complemented with rapid field visits in cases of doubts.

Paying agency (PA): The body(ies) responsible within a Member State for the management and control of CAP expenditure, notably controls, calculation and payment of CAP aid to the beneficiaries and their reporting to the Commission. Part of a PA’s work may be done by delegated bodies, but not payments to beneficiaries and their reporting to the Commission.

Programme period: Multiannual framework for planning and implementing EU policies,. The current programme period runs from 2014 to 2020 Rural development programmes funded by EAFRD are managed under this multiannual framework; EAGF is managed on a yearly basis.

Abbreviations

AAR: Annual activity report

CA: Competent Authority of the Member State (usually the Ministry of Agriculture)

CAP: Common Agricultural Policy

CB: Certification body

CF: Cohesion Fund

DG AGRI: Directorate General for Agriculture and Rural Development

EAFRD: European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development

EAGF: European Agricultural Guarantee Fund

ERDF: European Regional Development Fund

ERR: Error rate

ESF: European Social Fund

IACS: Integrated Administrative and Control System

IRR: ‘Incompliance’ rate

ISAs: International Standards on Auditing

ISSAIs: International Standards of Supreme Audit Institutions

MD: Management Declaration

PA: Paying Agency

Endnotes

1 Annex I to Council Regulation (EU, Euratom) No 1311/2013 of 2 December 2013 laying down the multiannual financial framework for the years 2014-2020 (OJ L 347, 20.12.2013, p. 884).

2 Where a payment is based on meeting certain conditions.

3 Article 59 of Regulation (EU, Euratom) No 966/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2012 on the financial rules applicable to the general budget of the Union and repealing Council Regulation (EC, Euratom) No 1605/2002 (OJ L 298, 26.10.2012, p. 1) (the ‘Financial Regulation’).

4 Regulation (EU) No 1306/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 December 2013 on the financing, management and monitoring of the common agricultural policy and repealing Council Regulations (EEC) No 352/78, (EC) No 165/94, (EC) No 2799/98, (EC) No 814/2000, (EC) No 1290/2005 and (EC) No 485/2008 (OJ L 347, 20.12.2013, p. 549) (the ‘CAP Horizontal Regulation’).