Working time reduction in the EU: recent patterns and main drivers

Working time has been on a long-term declining trend during the last decades in developed economies, including the EU. This trend has been driven by multiple factors, such as the reduction of the length of the working week, the increase in the share of part-time workers, and, recently, during the pandemic, the use of short-time work schemes to mitigate the economic impact of the health crisis. This chapter looks at how different groups of workers in different Member States have seen their working hours develop in recent years, and assesses what individual and societal factors have influenced these changes. Moreover, it looks at the economic evidence regarding the impacts of previous working time reductions.

Women and younger and older workers tend to work shorter weekly hours, while self-employed people, better-educated workers and people with migrant backgrounds tend to work longer hours. Those working longer hours tend to report more job strain than other workers. In Member States with longer average weekly hours and more average annual hours, overemployment is more likely to be present. Since 2015, the average preference for working time reduction increased, driven by a decline in preferred hours for more educated workers and for people who are better off financially. However, involuntary part-time workers, the majority of whom are women, would typically prefer to work longer hours per week.

Past experiences show that working time reductions can improve the well-being of the workers affected, albeit the impacts may not be uniform for all groups, and the intensification of work can counteract it. Rapid technological developments can lead to increasing productivity, and hence may allow for reductions in working time. At the macroeconomic level, in line with past developments, further reductions in hours worked may need to be compensated for either by increases in productivity, also driven by technological change; or in labour force participation, to avoid a negative impact on the level and growth of GDP.

Indeed, in the context of high labour shortages and a shrinking working-age population, the scope for mandatory legislative reductions in working hours may be limited, as they would reduce overall labour supply, but targeted flexibilities and working time reductions may also help to attract talent in some sectors or professions. At the same time, working time reductions may reduce the ability of some companies to effectively organise their services or production.

Working time policies, within the scope of the EU’s working time directive, can broaden the choice of weekly hours and eliminate labour market rigidities to better address the simultaneous presence of underemployment and overemployment in the EU labour market. This could involve reductions in weekly hours for some groups of workers, either through collective bargaining, or companies’ voluntary re-organisation of hours worked. On the other hand, working time policies can also support the underemployed, by broadening the options available to individuals and firms to adjust working hours without administrative barriers and respecting the upper limits on working time, while enforcing equal treatment between part-time and full-time employees and addressing the potential risks of flexibilization. Moreover, policies to address labour shortages could reduce the perceived overemployment of workers in shortage occupations by promoting an increased participation of workers with perceived underemployment, by promoting transitions in the labour market, with an emphasis on skills policies. Activation policies have been recommended to reduce involuntary part-time work and promote full participation in the labour market of women and vulnerable groups. To support this goal, measures to provide better access to quality care services for children and elderly people have proven especially effective.

Introduction

This chapter looks at the recent trends in working time in the EU.Working time, together with the number of persons employed, is an important determinant of labour supply and hence the contribution of labour to economic output in an economy. The amount of time worked is the quantity of time that is provided by workers on the labour market, at the price determined by wages. Macroeconomic analyses often focus on the number of persons employed and unemployed in an economy, as determinants of labour supply. This chapter focuses on the additional aspect of hours worked by those employed, and the factors that influence this, at both the individual and macroeconomic levels.

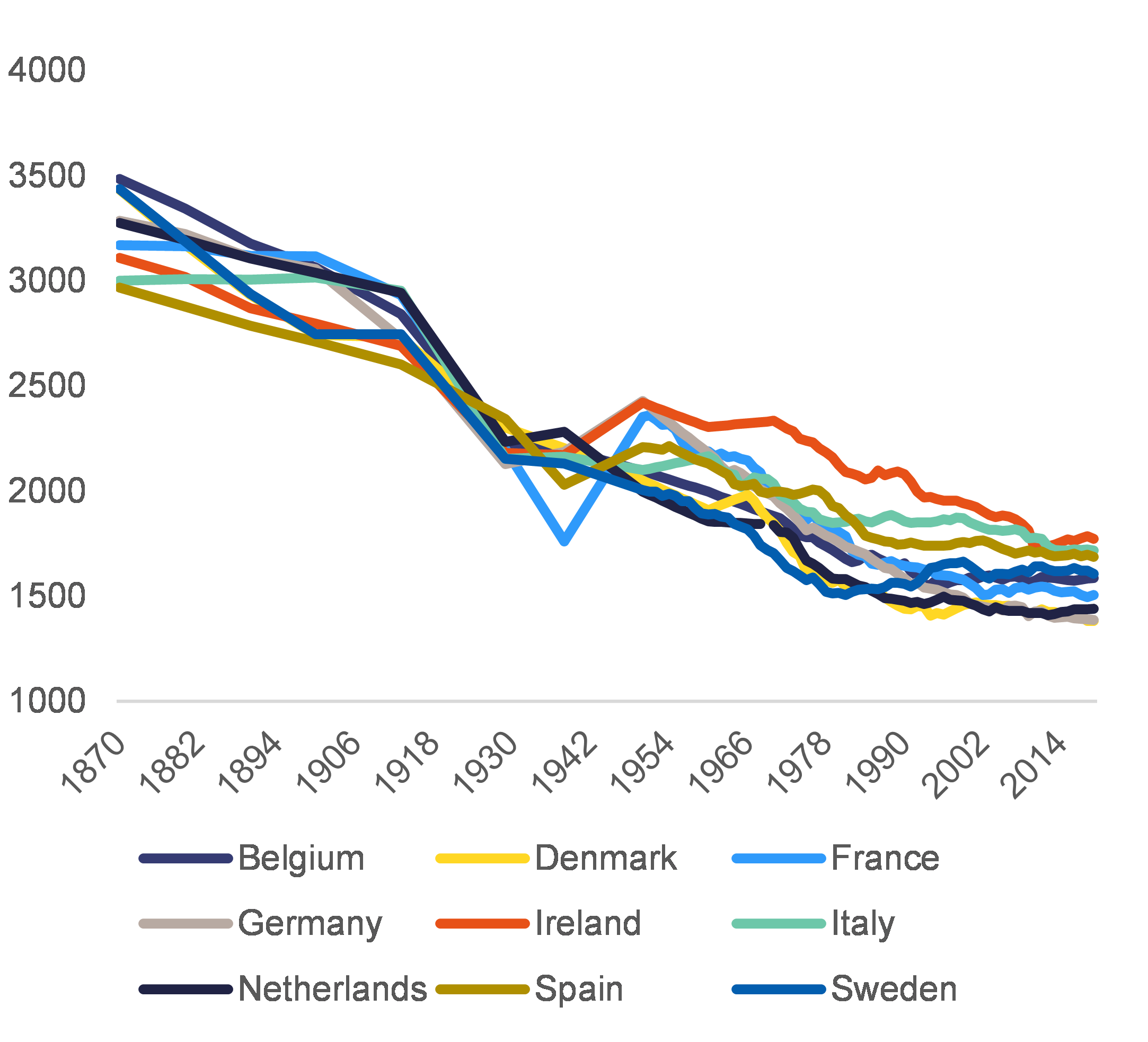

Working time in EU countries has been gradually declining over time, driven by both social and economic factors, such as technological progress.The trend in working time over the last 150 years is depicted in Graph 3.1. Between 1870 and 1973, the average annual hours worked per worker declined by more than a thousand hours in Germany, France, Italy and the Netherlands (Maddison, 2001). This amounts to a decline of 0.57 % per year (Boppart and Krusell, 2020). After 1973, the pace of the decline decelerated and became more uneven between countries. The main economic factor driving the long-term decline in hours worked per worker has been technological progress (Boppart and Krusell, 2020). Yet, this technological progress did not bring about the 15-hour working week, as famously predicted in 1930 by Keynes, who expected that the rise in living standards would allow people to meet their material needs with fewer hours of work, leaving them more leisure time.

Graph 3.1: Average annual working hours, nine Member States

Additional information about graph 3.1

The figure shows a graph of average annual working hours for 9 European countries (Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Netherlands, Spain, Sweden) between 1870 and 2020. All countries show similar long-term trends. In the late 19th century, the average annual working time in all countries was between 3500-3000 hours, with a decreasing trend until the 21st century, when the average annual working time was between 1500-2000 hours. The downward trend is considerable in the 19th and 20th centuries, being strongest during the Second World War, while in the 21st century the annual working hours are more stagnating.

Source

Feenstra et al. (2015) and Huberman and Minns (2007).

Working time regulations and other institutional factors have also influenced working time trends.Working time has been a core issue for the labour movement to improve working conditions, leading to the achievement of legislative milestones such as the 48-hour working week introduced after World War I (International Labour Organization convention of 1919), and the introduction of the 40-hour working week in developed countries (International Labour Organization convention of 1935) . The fall in working hours in the second half of the 20th century was steeper in the EU than in the United States. Differences in taxation and in the bargaining power of workers have been pinpointed as the main contributors to these differences. In the EU, the working time directive, issued in 1993 (replaced by the current directive in 2003), has shaped the working time regulations of Member States by specifying the maximum hours for the working day and week (13 hours per day and 48 hours per week, respectively, including overtime) .

Since 1995, the trends in working time have been mostly driven by shifts in labour force participation and part-time work. The main change in this respect has been the increasing labour force participation of women and the rise in part-time work . A major driver of the increase in the participation of women has been the rise in real wages in developed economies (Borjas, 2020). These shifts took place in parallel with a decline in working time and an increase in time available for leisure (Botelho et al., 2021).

Labour market policies can also favour adjustments of hours worked to tackle short-term shocks.As evidenced during the COVID-19 crisis, job-retention measures such as short-time work schemes can be a useful tool in preserving employment following a transitory shock, by allowing firms to temporarily reduce the number of hours worked by their employees. In this way, firms are able to keep their firm-specific human capital, while workers are at a lower risk of becoming unemployed, thereby mitigating the scarring effects that unemployment can have on individuals.

Recent economic and societal changes are shaping the organisation of working life and working time trends in a complex technological and demographic context.It can be hypothesised that the acceleration of digitalisation in the pandemic, along with the current rise in artificial intelligence, could lead to further technological change and potentially allow for a reduction and reallocation of working time linked to increased productivity levels and automation of tasks. At the same time, the pandemic contributed to the spread and acceptance of more flexible ways of working, such as teleworking . It also promoted a shift in worker preferences, towards an improved work-life balance . Even if those developments may ultimately prove to be temporary, in a context of high labour shortages after the pandemic, employers may improve their chances of recruitment by offering arrangements that cater to this, including by proposing more flexible or shorter working time. At the same time, shorter working time could in principle contribute to labour shortages. These developments take place in a context where demographic developments (population ageing) are leading to a shrinking working-age population, which in turn puts pressure on labour markets and welfare states, increasing the old-age dependency ratio, and raising the per-capita burden of public debt. In view of these developments, a public debate has resurfaced about the organisation of working time and about a possible move towards a 4-day working week, with or without a reduction in weekly working time .

This chapter focuses on the evolution of working time and its determinants, discussing in detail the topic of working time reduction.The chapter is structured as follows. First, it briefly summarizes the main insights from economic theory relevant for the analysis of working time and for working time reduction. Second, it outlines the most recent regulatory trends in working time. Third, it provides an overview of recent trends and developments in working time across the EU and Member States. Fourth, it presents empirical analysis on the individual and country-level determinants of working time. Finally, it discusses the lessons from past experiences with working time reduction policies, in the context of the re-emerging public debate on the topic.