Disinformation affecting the EU: tackled but not tamed

About the report:

Disinformation is a serious concern in organised societies. Social media and new technologies have increased the scale and speed with which false or misleading information can reach its audiences, whether intended and unintended. The EU action plan against disinformation was relevant at the time it was drawn up but incomplete. Even though its implementation is broadly on track and there is evidence of positive developments, it has not delivered all its intended results. We make recommendations to improve the coordination and accountability of EU actions against disinformation. We focus on the operational arrangements of the European External Action Service’s strategic communications division and its task forces. We recommend increasing Member States’ involvement in the rapid alert system and improving the monitoring and accountability of online platforms. We also point to the need for an EU media literacy strategy that includes combatting disinformation and taking steps to enable the European Digital Media Monitoring Observatory achieve its ambitious objectives.

ECA special report pursuant to Article 287(4), second subparagraph, TFEU.

Executive summary

IDisinformation has been present in human communication since the dawn of civilisation and the creation of organised societies. What has changed in recent years, however, is its sheer scale and the speed with which false or misleading information can reach its intended and unintended audiences through social media and new technologies. This may cause public harm.

IIThe European Council, in its conclusions of 28 June 2018, invited the EU’s High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy and the Commission to present an action plan with specific proposals for a coordinated response to disinformation. The EU action plan against disinformation, presented on 5 December 2018, includes ten specific actions based on four priority areas or ‘pillars’, and consolidates the EU’s efforts to tackle disinformation. EU spending on tackling disinformation has been relatively low to date: €50 million between 2015 and 2020.

IIIThe purpose of the audit was to assess whether the EU action plan against disinformation was relevant when drawn up and delivering its intended results. The audit covered the period from the run-up to the adoption of the EU action plan against disinformation in December 2018 until September 2020. This report is the first comprehensive, independent assessment of its relevance and the results achieved. Overall, we conclude that the EU action plan was relevant but incomplete, and even though its implementation is broadly on track and there is evidence of positive developments, some results have not been delivered as intended.

IVThe EU action plan contains relevant, proactive and reactive measures to fight disinformation. However, even though disinformation tactics, actors and technology are constantly evolving, the EU action plan has not been updated since it was presented in 2018. It does not include comprehensive arrangements to ensure that any EU response against disinformation is well coordinated, effective and proportionate to the type and scale of the threat. Additionally, there was no monitoring, evaluation and reporting framework accompanying the EU action plan, which undermines accountability.

VThe European External Action Service’s three strategic communications task forces have improved the EU’s capacity to forecast and respond to disinformation in neighbouring countries. However, they are not adequately resourced or evaluated, and their mandates do not cover some emerging threats.

VIThe EUvsDisinfo project has been instrumental in raising awareness about Russian disinformation. However, the fact that it is hosted by the European External Action Service raises some questions about its independence and ultimate purpose, as it could be perceived as representing the EU’s official position. The rapid alert system has facilitated information sharing among Member States and EU institutions. Nevertheless, Member States are not using the system to its full potential for coordinating joint responses to disinformation and common action.

VIIWith the code of practice, the Commission has established a pioneering framework for engagement with online platforms. We found that the code of practice fell short of its goal of holding online platforms accountable for their actions and their role in actively tackling disinformation.

VIIIThe report also highlights the absence of a media literacy strategy that includes tackling disinformation, and the fragmentation of policy and actions to increase capacity to access, understand and interact with media and communications. Finally, we found there was a risk that the newly created European Digital Media Observatory would not achieve its objectives.

IXBased on these conclusions, we recommend that the European External Action Service and the Commission:

- improve the coordination and accountability of EU actions against disinformation (European External Action Service and Commission);

- improve the operational arrangements of the StratCom division and its task forces (European External Action Service);

- increase participation in the rapid alert system by Member States and online platforms (European External Action Service);

- improve the monitoring and accountability of online platforms (Commission);

- adopt an EU media literacy strategy that includes tackling disinformation (Commission);

- take steps to enable the European Digital Media Observatory to fulfil its ambitious objectives (Commission).

Introduction

01The European Commission1 defines “disinformation” as the “creation, presentation and dissemination of verifiably false or misleading information for the purposes of economic gain or intentionally deceiving the public, which may cause public harm”. Such public harm includes threats to democratic political and policy-making processes as well as to the protection of EU citizens' health, the environment or security.

02The Commission’s definition of disinformation excludes misleading advertising, reporting errors, satire and parody, or clearly identified partisan news and commentary. Unlike hate speech or terrorist material, for example, false or misleading information is not illegal on its own.

03The EU’s legitimacy and purpose rest on a democratic foundation, which depends on an informed electorate expressing its democratic will through free and fair elections. Any attempt to maliciously and intentionally undermine or manipulate public opinion therefore represents a grave threat to the EU itself. At the same time, combatting disinformation represents a major challenge, as it should not impair the freedom of opinion and expression enshrined in the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights.

04The term “disinformation” emerged in the early 20th century and has been used extensively ever since. In recent years, the internet has amplified the scale and speed with which false information is reaching audiences, often anonymously and at minimal cost.

05EU efforts to combat disinformation date back to March 2015, when the European Council2 invited the EU’s High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy (the “High Representative”), in cooperation with the Member States and EU institutions, “to develop an action plan on strategic communication to address Russia’s ongoing disinformation campaigns”. This led to the creation of the strategic communications division (“StratCom”) and the first of its task forces within the European External Action Service (EEAS), with a mandate to counter disinformation originating outside the EU (Russia) and design and disseminate positive strategic communications in the EU’s eastern neighbourhood – known as the East strategic communications task force. In 2017, two more StratCom task forces were created: one for the southern neighbourhood and another for the Western Balkans (see also paragraphs 45-49).

06In late 2017, the Commission set up a high-level expert group to offer concrete advice on tackling disinformation. The group delivered its report in March 20183, which formed the basis for the Commission’s “Communication on tackling online disinformation: a European approach”4 (April 2018). This Communication outlined key overarching principles and objectives to guide action to raise public awareness about disinformation, as well as the specific measures the Commission intended to take.

07The European Council, in its conclusions of 28 June 20185, invited the EU’s High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy and the Commission to “present an action plan by December 2018 with specific proposals for a coordinated EU response to the challenge of disinformation, including appropriate mandates and sufficient resources for the relevant EEAS Strategic Communications teams”.

08Based on the April 2018 communication, the Commission published an EU action plan against disinformation in December 2018 (hereinafter: the “EU action plan”). It sets out ten specific actions based on four priority areas or ‘pillars’ targeting society as a whole, as shown in Table 1 below.

Table 1

The pillars and actions of the EU action plan against disinformation

| Pillar | Actions |

| I. Improving the capabilities of EU institutions to detect, analyse and expose disinformation | (1) Strengthen the strategic communications task forces and EU delegations with additional resources (human and financial) to detect, analyse and expose disinformation activities (2) Review the mandates of the South and Western Balkans strategic communications task forces. |

| II. Strengthening coordinated and joint responses to disinformation | (3) By March 2019, establish a rapid alert system among Member States and EU institutions that works closely with other existing networks (such as NATO and G7) (4) Step up communication before the 2019 European Parliament elections (5) Strengthen strategic communications in the Neighbourhood. |

| III. Mobilising private sector to tackle disinformation | (6) Closely and continuously monitor the implementation of a code of practice to tackle disinformation, including pushing for rapid and effective compliance, with a comprehensive assessment after 12 months |

| IV. Raising awareness and improving societal resilience | (7) With Member States, organise targeted campaigns to raise awareness of the negative effects of disinformation, and support work of independent media and quality journalism (8) Member States should support the creation of teams of multi‑disciplinary independent fact-checkers and researchers to detect and expose disinformation campaigns (9) Promotion of media literacy, including through Media Literacy Week (March 2019) and rapid implementation of the relevant provisions of the Audio-visual Media Services Directive (10) Effective follow-up of the Elections Package, notably the Recommendation, including monitoring by the Commission of its implementation |

Source: ECA, based on the EU action plan.

There is no EU legal framework governing disinformation apart from article 11 of the Charter on Fundamental Rights on the Freedom of expression and information, and a series of policy initiatives. Responsibility for combatting disinformation lies primarily with the Member States6. The EU's role is to support the Member States with a common vision and actions aimed at strengthening coordination, communication and the adoption of good practices. Annex I presents the main departments and offices of the EU institutions involved in the implementation of the EU action plan. As Annex II shows, EU spending on tackling disinformation has been relatively low to date: €50 million between 2015 and 2020.

10In December 20197, the Council confirmed that the EU action plan “remains at the heart of the EU’s efforts” to combat disinformation, and called for it to be reviewed regularly and updated where necessary. It also invited the EEAS to reinforce its strategic communication work in other regions, including sub-Saharan Africa. The European Parliament has also on numerous occasions expressed the importance of strengthening efforts to combat disinformation8.

11In early 2020, almost immediately following the COVID‑19 outbreak, an unprecedented wave of misinformation, disinformation and digital hoaxes appeared on the internet, which the World Health Organization described as an “infodemic”9. This posed a direct threat to public health and economic recovery. In June 2020, the European Commission and the High Representative published a communication entitled “Tackling COVID‑19 disinformation - Getting the facts right”10, which looked at the steps already taken and concrete actions to follow against disinformation regarding COVID‑19.

12On 4 December 2020, the Commission presented the “European democracy action plan”11, part of which is dedicated to strengthening the fight against disinformation. It builds on existing initiatives in the EU action plan against disinformation. Furthermore, the Commission also issued a proposal for a Digital Services Act12 proposing a horizontal framework for regulatory oversight, accountability and transparency of the online space in response to the emerging risks.

13Figure 1 provides a timeline of the main EU initiatives since 2015.

Figure 1

Timeline of main EU initiatives against disinformation

Source: ECA.

Audit scope and approach

14This audit report comes two years after the adoption of the EU action plan against disinformation. It is the first comprehensive, independent assessment of its relevance and the results achieved, thereby contributing to the regular review of the EU action plan requested by the Council.

15The aim of our audit was to ascertain whether the EU action plan against disinformation is relevant and delivering its intended results. To answer this question, we addressed two sub-questions:

- Is the EU action plan relevant for tackling disinformation and underpinned by a sound accountability framework?

- Are the actions in the EU action plan being implemented as planned? To answer this sub-question, we assessed the status of the actions under each of the four pillars of the plan.

The audit covered the period from the run-up to the adoption of the EU action plan against disinformation in December 2018 until September 2020. Where possible, this report also refers to recent developments in this area after this date, such as the Commission’s presentation of the European democracy action plan and the proposal for a Digital Services Act in December 2020 (see paragraph 12). However, as these documents were published after we had completed our audit work, they are beyond the scope of this audit.

17The audit included an extensive desk review and analysis of all available documentation on the structures put in place, and the actions planned and implemented through the EU action plan. We sent a survey to the 27 Member States’ Rapid Alert System contact points, with a response rate of 100 %. We also held meetings with numerous stakeholders such as the EEAS and relevant Commission directorates-general (DGs), the European Parliament, the Council, Commission representations, NATO, the NATO-affiliated Strategic Communication Centre of Excellence in Latvia, national authorities, online platforms, journalist and fact-checking organisations, audio-visual media services regulating bodies which provide advice to the Commission, academics and experts, project managers/coordinators and an external expert.

18We also assessed 20 out of 23 projects the Commission identified as being directly related to fighting disinformation through media literacy. Annex III summarises our assessment of these projects.

Observations

The EU action plan against disinformation was relevant when drawn up, but incomplete

19For this section, we examined whether the EU action plan had been relevant when first drawn up, i.e. whether it addressed the needs identified by experts and other stakeholders. We also assessed whether it had been reviewed and updated. We looked at the events and sources it was based on, and assessed whether it contains adequate coordination arrangements for communication and the elements necessary for measuring implementation performance and ensuring accountability.

The EU action plan was broadly consistent with experts’ and stakeholders’ views on disinformation

20Fighting disinformation is a highly technical domain that requires input and expertise from a diverse range of professionals. Public consultation is also essential to establish the views and priorities of stakeholders and to understand the threat better.

21We found that the Commission had relied on appropriate external expertise and undertaken a comprehensive public consultation13 as a basis for the EU action plan. The EU action plan largely addressed the suggestions and concerns expressed in these documents.

22At the time the EU action plan was published in December 2018, it presented a structured approach to address issues requiring both reactive (debunking and reducing the visibility of disinformation content) and proactive longer-term efforts (media literacy and measures to improve societal resilience). It emphasised the goal of protecting the upcoming 2019 European elections, as well as long-term societal challenges requiring the involvement of many different actors.

23Except in the area of media literacy, the Commission identified concrete actions to follow the main recommendations from the report of the independent ‘High-level expert group on fake news and online disinformation’ (HLEG). The HLEG, consisting of 39 experts with different backgrounds, was set up in January 2018 by the Commission to advise on policy initiatives to counter disinformation online. This report, together with the Commission’s April 2018 communication formed the basis for the EU action plan.

24Further evidence of the EU action plan’s relevance is that its actions sought to engage a broad array of key stakeholders in the area, including not only EU institutions and Member States, but also others such as the private sector, civil society, fact-checkers, journalists and academia.

The EEAS and the Commission did not establish clear coordination arrangements to implement the EU action plan

25The EU action plan against disinformation was not accompanied by an overall coordination framework to ensure that any EU response is effective and proportionate to the type and scale of the threat. Defining and coordinating communication workflows, for example, would make it possible to identify when to work together and in partnership with local actors and civil society to raise awareness about disinformation threats.

26A communication strategy ensures a coherent response when different actors are involved. Each of the EU action plan’s four pillars is under the responsibility of a different Commission DG or the EEAS. This creates the risk of them ‘working in silos’ (i.e. in parallel without cooperation or coordination) when it comes to communication, without any single body being in charge or having complete oversight of all communication to combat disinformation.

27The Commission’s Directorate-General for Communication (DG COMM) is responsible for external communication for the institution. DG COMM’s management plan for 2019 recognises its role in tackling disinformation and highlights the need for cooperation among DGs and other institutions, referring in particular to the Directorate-General for Communications Networks, Content and Technology (DG CNECT) and the Joint Research Centre. However, there is no mention of the EEAS or the StratCom task forces, which are also very much involved in positive communication and fighting disinformation.

28DG COMM has established an internal network against disinformation (IND). Its aims include improving coordination of communication activities on tackling disinformation, establishing an online repository of validated rebuttals, systematically detecting disinformation and coordinating the response, and promoting positive messaging. Eleven meetings took place between its inception in May 2018 and January 2020. These meetings are broadly inclusive, with representatives from many Commission services and representations, the EEAS and other institutions, as well as other experts. However, the meetings so far have only involved representatives sharing information on action taken, with no connection to policy-making and no evidence of concrete follow-up actions or decisions taken to make the IND an effective coordination mechanism.

29DG COMM’s 2019 management plan had only one indicator related to disinformation (out of 102) and this only measured the number of IND meetings.

30In addition, the Commission representations play a vital role in the Commission’s external communication, through positive messaging and outreach, media briefings, debunking myths and fighting disinformation, and are expected to participate actively in the IND. Their myth-busting activities are listed on a page on each official representation website. These pages were often difficult to access as their location varied between representations: some (e.g. in Greece and Spain) included it under the news section, while others (e.g. in Poland and Ireland) did not. They were also not regularly updated. Some pages provided limited, often-anecdotal information and there were no statistics available on the number of visitors to these pages.

31Finally, DG COMM was developing a central web-based disinformation hub as a centralised portal bringing together all aspects of the EU institutions’ work on disinformation. Its launch was due in early 2020 but it has been cancelled for unclear reasons.

A piecemeal monitoring and reporting framework and the lack of long-term funding undermine the EU action plan’s accountability

32To ensure accountability, an action plan needs clear objectives and time-bound actions, accompanied by a number of indicators for monitoring performance. Provisions for financing, regular reporting, evaluation and revisions are also essential elements of an action plan.

33Some objectives in the EU action plan have generic wording such as “step up” or “strengthen”, which do not lend themselves to measurement. No overall KPIs exist for the EU action plan as a whole. In addition, half of the actions (actions 1, 2, 4, 5 and 8) have no KPIs and the actions are either not clearly defined or time bound (see also Annex IV).

34The timeframe of the actions varies between short- and long-term, and some are concrete and time-bound (e.g. “by March 2019, the Commission and the High Representative, in cooperation with Member States, will establish a Rapid Alert System”), while others are vague (e.g. “Member States should significantly strengthen their own communication efforts on Union values and policies”).

35The EU action plan was not accompanied by a dedicated monitoring and evaluation framework (this applies also to the recently published European democracy action plan). There was no provision to evaluate the plan as a whole and there has been no overall evaluation to date. Feedback from its implementation in the Member States is not recorded centrally and not aggregated. Each representation carries out its own communication campaign and collects statistics, but we did not find any evidence of those statistics being used by the Commission for lessons learned, best practice, or as a baseline. There is no reporting beyond stating that some activities belong to the category of efforts against disinformation. For example, tools such as the Commission’s internal myth-busting wiki or the newsletter against disinformation are not monitored in terms of Member State engagement (e.g. using surveys, user statistics or indicators).

36The Commission and EEAS regularly update and report to various Council working parties and preparatory bodies on progress in implementing actions under specific pillars of the EU action plan. However, this reporting is not in the public domain and does not encompass the whole EU action plan.

37Although there have been separate reports on specific aspects of the EU action plan (an assessment of the code of practice and a Commission report on the EU elections), only one report on the implementation of the EU action plan as a whole has been published. This was on 14 June 2019, six months after the presentation of the EU action plan itself.

38Although this first implementation report covered all pillars of the EU action plan, it has a number of shortcomings:

- it does not provide any measure of performance;

- except for the code of practice, reporting for each pillar is mostly in a general narrative form and there is no detailed reporting for each action;

- there is no reporting annex on individual projects linked to the EU action plan;

- there is no indication of when to expect the next implementation report.

Fighting disinformation is a constantly evolving area, which would merit regular reporting. The Joint Communication on tackling COVID‑19 disinformation recognised the need to develop regular reporting14.

40The EU action plan lacks a dedicated financial plan covering the costs of all activities assigned to different entities. Financing comes from different sources and there are no provisions to secure funding in the long term, even though some of the events mentioned in the EU action plan are recurring. Annex II presents the budget allocated to the different actions to combat disinformation. It shows that the main source of funding is different every year and exposes a lack of financial planning (see also paragraphs 50-51). The Commission and the EEAS do not always earmark expenditure linked to fighting disinformation (it has no specific intervention code) – such information has been compiled only for this audit. Figure 2 gives an overview of all EU funding against disinformation from 2015 to 2020 (it does not include activities that contribute indirectly to combatting disinformation, namely the pro-active communications activities in the EU’s neighbourhood).

Figure 2

All EU funding against disinformation 2015-2020

Source: ECA, based on Commission and EEAS information.

Furthermore, the EU action plan has not yet been updated since it was presented in 2018. For example, some actions are linked only to the 2019 European elections or the 2019 Media Literacy Week, both of which have passed. Disinformation is constantly evolving. The tactics used, the technology behind disinformation campaigns, and the actors involved are all constantly changing15. The Council also highlighted the need to regularly review and update the EU action plan (see paragraph 10).

42Although the COVID‑19 disinformation communication (June 2020), the European democracy action plan and the proposal for a digital services act extend certain actions originally set out in the EU action plan, they cannot be considered a comprehensive update thereof. Moreover, having actions pursuing similar objectives in different action plans and initiatives makes coordination more complex, increasing the risk of inefficiencies.

The implementation of the EU action plan is broadly on track, but has revealed a number of shortcomings

43This section assesses the implementation of the actions under each of the four pillars of the EU action plan and the extent to which they have improved the way the EU tackles disinformation.

The strategic communications task forces play an important role but are not adequately staffed or funded to deal with emerging threats

44Under pillar I of the EU action plan, we examined the EEAS StratCom task forces. We looked at their mandate and determined whether they were adequately staffed and sufficiently funded. In this context, we also examined the role and position of EUvsDisinfo, an EU flagship project against disinformation.

The StratCom task forces’ mandates do not adequately cover the full range of disinformation actors

45Apart from improving the EU’s capacity to forecast and respond to external disinformation activities (the StratCom task forces’ mandates do not cover disinformation generated within the EU), the StratCom task forces have contributed greatly to effective communication and promoting EU policies in neighbouring regions.

46The mandates of the three StratCom task forces (East, Western Balkans and South) have grown out of a series of Council Conclusions, with differences in tasks and focus. For example, the mandate of the East StratCom task force specifically covers the task “challenge Russia’s ongoing disinformation campaigns”16. The East StratCom task force’s mandate was defined in terms of a single, external malign actor rather than protecting Europe from disinformation regardless of source.

47This was not the case for the other two StratCom task forces, whose original focus was stepping up communication activities in their respective regions. The South StratCom task force was established to cover the EU’s southern neighbourhood and the Gulf region, while the Western Balkans task force was established to enhance strategic communications in that region. Prior to the December 2019 Council Conclusions17, addressing disinformation was not the central priority of either task force. Only the East StratCom task force had the explicit objective of strengthening the capacity to forecast, address and respond to disinformation. Table 2 below sets out each StratCom task force’s objectives at the time of the audit.

Table 2

Comparison of the StratCom task forces’ objectives

| StratCom Task force | East | Western Balkans | South |

| Objectives |

|

|

|

Source: EEAS.

48The three StratCom task forces are distributed widely across different regions and cover different agents of disinformation. Nevertheless, the StratCom task forces’ media monitoring activities focus extensively on Russian international media, Russian official communication channels, proxy media, and/or media inspired/driven by the Russian narrative, operating in the EU and its neighbourhood. However, according to EEAS analysis, other actors such as China have emerged to varying degrees as prominent disinformation threats. In this respect, the new European Parliament committee on foreign interference (INGE) has also held hearings to discuss potential threats from third countries18.

49The StratCom task forces’ mandate is a political one, which does not specifically spell out their policy objectives and is not underpinned by a firm legal foundation. Under action 2 of the EU action plan, the High Representative was meant to review the mandates of the South and West Balkans StratCom task forces (but not the East task force). However, this review was never done. The EEAS considers that the Council Conclusions adopted in December 2019, by stating explicitly that “all three Task Forces should be able to continuously detect, analyse and challenge disinformation activities”19, provides sufficient basis for (re-)affirming their mandates. The Council also invited the EEAS to assess its needs and options for expanding to other geographical areas, which demonstrates that political support exists to broaden the scope of the StratCom task forces.

The StratCom task forces do not have a dedicated and stable funding source

50When it was set up in 2015, the East StratCom task force was not provided with any resources of its own and was funded out of the administrative expenditure of the EEAS and the Commission’s Service for Foreign Policy Instruments. The EU action plan boosted the funding available for the EEAS StratCom task forces. In fact, strategic communications is the only part of the action plan whose specific budget has increased. As Figure 2 above shows, the budget for the StratCom task forces and strategic communications has increased nearly fourfold since the action plan was adopted.

51Even though disinformation is not just a short-term threat, the StratCom task forces do not have a stable funding source, which could threaten their sustainability. For example, a significant source of funding for the StratCom task forces has been a European Parliament preparatory action called ‘StratCom Plus’ (see Annex II). By their nature, preparatory actions are designed to prepare new actions like policies, legislation and programmes. Figure 3 illustrates how the added funding has been allocated to improving different capabilities.

Figure 3

Funding by the 'StratCom Plus' preparatory action of different EEAS StratCom capacities (2018-2020)

Source: ECA, based on EEAS data.

The importance of funding and adequate resourcing has been stressed on numerous occasions20, including by the European Parliament21, Member States22 and civil society23. However, stakeholders differ in their opinions about how to prioritise the available EU funding to fight disinformation. Based on our interviews, some Member States feel greater emphasis should be placed on analysing and monitoring those sources and actors to which disinformation can be more easily attributed. Others feel more funding should be allocated to positive communication.

Staffing needs not yet satisfied

53The EU action plan envisaged strengthening the StratCom division by adding 11 positions ahead of the European elections, recruiting permanent officials in the medium term and new staff in the EU delegations “to reach a total increase of 50-55 staff members” by the end of 2020. The recruitment plan has been implemented in three phases: (1) redeployment of contract staff within the EEAS; (2) recruitment of staff to the StratCom team; and (3) addition of staff across 27 EU delegations in the EU neighbourhood.

54The StratCom division is still in the process of recruiting and deploying staff. As of October 2020, it had 37 staff and had therefore not yet reached the total increase of 50-55 staff, as stated in the EU action plan. One reason why it has been difficult to meet this target is that many StratCom staff are seconded from the Council, the Commission and the Member States and some have been withdrawn from their secondments.

55Almost all staff reinforcements (including all the redeployments) have been contract staff: the EEAS acknowledged that it is not easy to recruit permanent officials with the necessary expertise and skills needed to perform the duties required. However, despite their important contribution, contract staff have a maximum tenure of six years.

56The other group that makes up a significant portion of StratCom capacity is seconded national experts. These have primarily supported the work of the East and recently also the Western Balkans StratCom task force. As well as benefitting the EEAS, their secondment benefits their home countries by allowing them to obtain more expertise and create deeper connections with the EEAS. However, overreliance on secondment can result in uncertainty in staffing and periodic loss of institutional memory and expertise due to frequent turnover. All of these factors potentially undermine the building of institutional memory and expertise.

57In light of the COVID‑19 pandemic and the additional workload it has created for the task forces, there is a risk that the EEAS, with the current distribution and number of staff, will have insufficient capacity to keep pace with new trends and developments like emerging threat sources and disinformation strategies and tactics. Moreover, the Council’s request to reinforce strategic communications work in other regions (see paragraph 10) may further stretch its limited staffing capacity.

58Effective data analysis is critical not only for monitoring, detecting and analysing disinformation, but also as a basis for sound, evidence-based strategic insights and policy-making. At the time of the audit, the StratCom division’s data analysis cell includes full-time in-house analysts, who are supported by external contractors. The cell, launched in mid-2019, supports the work of the StratCom task forces and the rapid alert system (RAS) under pillar II of the EU action plan. Its analyses are predominantly on demand and ad hoc. In addition, its work is not integrated in a structured manner into the work of all the StratCom task forces. Although relying on external contractors can provide flexibility, in-house capacity is critical to provide sensitive analysis at short notice and to build institutional memory and expertise.

Measuring the impact of the StratCom task forces’ work remains a challenge

59The greatest challenges in strategic communications remain measuring vulnerability to and the impact of disinformation, as well as efforts to understand, analyse and respond to it. The Commission uses opinion polling as one way to assess the effectiveness of strategic communications to influence perceptions about the EU. However, it is difficult to attribute the results of this polling to EU actions.

60Beyond the communication campaigns, the StratCom task forces did not comprehensively measure the impact of their work. Furthermore, none of them had an evaluation function to assess their effectiveness and identify areas for improvement.

The hosting of EUvsDisinfo by the EEAS creates uncertainty about the project’s ultimate purpose

61EUvsDisinfo is the public face and flagship of the EU’s efforts to combat disinformation, and the East task force’s main anti-disinformation product. It has a searchable, open-source database, with more than 9 700 disinformation cases as of 1 October 2020. Key materials on the EUvsDisinfo website are published in five EU languages; the rest is in English and Russian only. According to the EEAS, the original focus on Russian disinformation provided the foundation for a unique and pioneering approach; there are no comparable initiatives by Member State governments.

62From its beginnings in 2015, EUvsDisinfo has steadily built up visibility online (see Figure 4 below) by cataloguing, analysing and publishing examples of Russian disinformation. Many stakeholders confirmed that EUvsDisinfo has been instrumental in raising awareness and influencing perceptions about the Russian disinformation threat to the EU and its Member States.

Figure 4

EUvsDisinfo: Number of visitors, unique page views and Twitter and Facebook followers

Source: ECA, based on EEAS information.

However, EUvsDisinfo has also faced criticism in the past. For example, it was censured by the Dutch parliament24 in 2018 for erroneously attributing Russian disinformation to a Dutch domestic publication. Furthermore, some cases published on EUvsDisinfo do not represent a threat to EU democracies.

64Looking ahead, the future role and mission of EUvsDisinfo are unclear, beyond producing more examples of Russian disinformation – a threat that is now well established and acknowledged. Despite the EEAS’s claims that EUvsDisinfo is independent and does not represent the EU’s official position, its location within the EEAS makes this questionable. This raises the question of whether such an instrument should be hosted and run by a public authority (such as the EEAS) or whether it should be run under the responsibility of a civil society organisation.

The RAS has brought Member States together but has not lived up to its full potential

65The establishment of the rapid alert system (RAS) is the key action under pillar II of the EU action plan (action 3). As the plan states, “The first hours after disinformation is released, are critical for detecting, analysing and responding to it”. The RAS was established in March 2019, by the deadline set in the plan. It has two key elements: a network of national contact points and a web-based platform whose aim is to “to provide alerts on disinformation campaigns in real-time through a dedicated technological infrastructure” in order to “facilitate sharing of data and assessment, to enable common situational awareness, coordinated attribution and response and ensure time and resource efficiency”25. The EEAS provides the secretariat for the RAS and hosts the website.

Although a useful tool for sharing information, the RAS had not yet issued alerts at the time of the audit and has not been used to coordinate common action

66In order to work effectively, the RAS must be able to issue timely alerts, coordinate common attribution and response and facilitate exchange of information between Member States and EU institutions. We examined whether the RAS had been operational before the 2019 European elections, as stipulated in the EU action plan. We also assessed its activity and the level of engagement of its participants.

67We found that the RAS was set up quickly in March 2019 as envisaged in the EU action plan. It has brought together Member States and EU institutions, and has facilitated information sharing, but it had not issued alerts at the time of the audit and has not coordinated common attribution and response as initially envisaged.

68Most stakeholders consulted during our audit had a positive view of the RAS. For them, it fills an important gap in the counter-disinformation ecosystem by creating a community. This was also confirmed by our survey of Member States: the RAS allows them to share information, obtain new insights and mutually strengthen their capabilities. Figure 5 below presents the aspects most valued by the national RAS contact points.

Figure 5

Member States’ ratings of importance of elements of the RAS

Source: ECA.

Despite this positive opinion of the RAS as an information exchange tool, we found no evidence that the information shared through the RAS had triggered any substantial policy developments at Member State level. Building common situational awareness remains a work in progress for the RAS, hampered by the absence of harmonised and consistent definitions (e.g. of the term disinformation itself, and differing views on its sources, responses, levels of preparedness, etc.) and lack of common risk assessment.

70When the RAS was launched, providing real-time alerts to react swiftly to disinformation campaigns was considered its primary purpose, driven by the urgency of the upcoming European elections. For the StratCom team, however, the key aim was to bring practitioners together and develop a community, as no such mechanism previously existed in the EU. These differing motives have obscured understanding among stakeholders and the wider public of what the RAS does.

71An alert mechanism has been developed, which can be used in extremely urgent cases, but it had not been activated at the time of the audit. A threshold for triggering the alert system has been defined in qualitative terms: a disinformation campaign that has ‘transnational significant impact’ (i.e. a targeted attack on several countries). However, a quantitative assessment of this threshold is not possible.

72In addition to the alert function, the RAS was conceived to help attribute disinformation attacks to their source and promote a coordinated response. However, this coordination capacity of the RAS has not been tested.

Activity and engagement in the RAS are driven by a limited number of Member States

73The RAS brings together the contact points of the Member States, the Intelligence and Situation Centre of the EEAS, the European Commission (especially DGs CNECT, JUST and COMM), the European Parliament and the General Secretariat of the Council. Representatives from NATO, the G7 Rapid Response Mechanism participate in the rapid alert system. Outside experts, including from civil society and online platforms, are also sometimes present during RAS meetings. Generally, meetings of the national contact points take place every quarter, but the level of engagement varies between different Member States. Most activity is driven by one third of the Member States, which participate more regularly and are more active in the meetings.

Latest statistics point to a downward trend in activity levels

74The statistics generated by the platform point to a number of trends. Firstly, activity is driven by a small number of core users, with other users being much more passive. Secondly, since its launch, activity levels have peaked around two main events: the European elections and the early weeks following the general lockdown in mid-March 2020. However, in the case of the latter, these have since come down and stabilised at the end of August 2020 at around half the levels in May.

75The user statistics point to a downward trend in activity levels. For example, average daily views – even in the specific parts of the RAS that focus on COVID‑19 disinformation – have declined, as shown in Figure 6. In addition, the number of actively engaged users has been in steady decline since the European elections in late May 2019. While these metrics do not tell the full story, they indicate clearly that the platform is not living up to its full potential.

Figure 6

Average number of RAS users from March 2019 to March 2020

Source: EEAS StratCom. The two drops in the user number is a result of the policy introduced in August to deactivate user accounts that have not been active for more than three months.

Cooperation with online platforms and existing networks is mostly informal

76According to the EU action plan, online platforms should cooperate with the RAS contact points, in particular during election periods, to provide relevant and timely information. However, there is no protocol establishing cooperation between the RAS and the online platforms and as the StratCom team does not monitor the number of cases flagged, it is not possible to assess the RAS’s performance in this area.

The code of practice made online platforms adopt a stance against disinformation but stopped short of making them accountable

77One of the main reasons why disinformation is so acute is the widespread use of the internet, combined with the advent of new technologies and the ever-increasing use of online platforms to access information. This greatly facilitates the creation, amplification and dissemination of false information. According to the Digital Economy and Society Index, in 2020, 85 % of EU citizens were internet users. Most platforms monetise their services through their handling of personal data (mainly based on advertising models). This created a fertile ground also for disinformation actors, allowing them to better target their actions.

78In the case of online platforms, disinformation occurs mostly as a result of users sharing false information, which can then be promoted by the platforms’ algorithms to prioritise the display of content. These algorithms are driven by the online platforms’ business model, and they privilege personalised and popular content, as it is more likely to attract attention. Disinformation also affects web search results, which further hinders users in finding and reading trustworthy online information26. Picture 1 below shows an example of the search predictions provided by an online platform for the term “The EU is”, which are almost all negative.

Picture 1

Example of predictions from an online platform when searching for “The EU is”

Source: ECA actual internet search on 18 October 2019 at 11:55 (GMT +1).

Google is a trademark of Google LLC.

Fake accounts, internet trolls and malicious bots also contribute to the dissemination of false information.

The CoP provides a framework for the Commission to interact with social media platforms

80Following the April 2018 Commission communication and the HLEG proposals, the Commission decided to engage with online platforms and other trade associations on the subject of disinformation. This led to the creation of the code of practice (CoP) (see Annex V), adopting a voluntary approach based on self-regulation by the signatories. The CoP was signed in October 2018, before being incorporated into the EU action plan under pillar III. Presently it has 16 signatories.

81The CoP committed online platforms and trade associations representing the advertising sector to submit reports to the European Commission setting out the state of play regarding measures taken to comply with their commitments. These measures ranged from ensuring transparency in political advertising to closing fake accounts and preventing purveyors of disinformation from making money. The Commission closely monitored their compliance with these commitments.

82Most of the stakeholders interviewed during the audit stressed that the Commission’s engagement with online platforms was a unique and necessary initiative. Many of those from outside the EU whom we consulted are observing the Commission’s efforts closely. They see the EU as the first global player trying to achieve the delicate balance between protecting freedom of expression and limiting malign spread of harmful disinformation.

83The CoP provided a framework for the Commission to interact with social media platforms ahead of the EU elections in May 2019 and later during the COVID‑19 pandemic to mitigate the negative effects of the related “infodemic”. Box 1 presents EU efforts to limit COVID‑19 related disinformation through the CoP (see also Annex VI).

Box 1

EU efforts to limit the COVID‑19 “infodemic” through the CoP

In March 2020, when the impact of the COVID‑19 pandemic became more apparent, meetings took place between the Commission and the social media platforms. The Commission requested that the platforms give more prominence to information from authoritative sources and remove false advertising.

In June 2020, the European institutions published a joint communication entitled “Tackling COVID‑19 disinformation - Getting the facts right”. The communication highlights the role of the EU action plan.

The signatories to the CoP presented their efforts through dedicated reporting, which was published in September27 and October 202028. Below are some examples of these efforts, taken from the platforms’ reports:

- Google blocked or removed over 82.5 million COVID-19-related advertisements in the first eight months of 2020, and in August 2020 alone Microsoft Advertising prevented 1 165 481 ad submissions related to COVID‑19 from being displayed to users in European markets.

- In August 2020, over 4 million EU users visited authoritative sources on COVID‑19 as identified by search queries on Microsoft’s Bing. Facebook and Instagram reported that more than 13 million EU users visited their COVID‑19 “information centre” in July and 14 million in August.

- Facebook displayed misinformation warning screens associated with COVID‑19-related fact-checks on over 4.1 million items of content in the EU in July and 4.6 million in August.

Platforms have different moderation policies. Their reports have different formats and data are difficult to compare, as the terminology used by the companies differs. Facebook analyses “coordinated inauthentic behaviour” and “influence operations” while Twitter reports on “manipulative behaviour”. While Google and Microsoft reported removing millions of advertisements, Twitter stated that it did not find a single promoted tweet containing misinformation. Despite these discrepancies, the Commission considered that “In general, the reports provide a good overview of actions taken by the platforms to address disinformation around COVID‑19”.

The assessment of the CoP revealed limitations in the reporting requirements

84A number of reviews and evaluations have assessed the CoP. They revealed several shortcomings concerning the way the Commission established reporting requirements for the signatories to the CoP (see Box 2). These evaluations had not led to any changes in the CoP.

Box 2

Evaluations of the code of practice

An initial assessment of the CoP, before it was signed, was made by the Sounding Board of the multi-stakeholder Forum on disinformation29 on 24 September 2018. It stated that: “…the “Code of practice”, as presented by the working group, contains no common approach, no clear and meaningful commitments, no measurable objectives or KPIs, hence no possibility to monitor progress, and no compliance or enforcement tool: it is by no means self-regulation, and therefore the Platforms, despite their efforts, have not delivered a Code of Practice.” Some elements of this opinion are still relevant today and were reflected in subsequent assessments and evaluation of the CoP.

The European Regulators Group for Audiovisual Media Services (ERGA) presented an opinion on the CoP in April 202030. It identified three main weaknesses:

- lack of transparency about how the signatories are implementing the CoP;

- CoP measures are too general in content and structure;

- limited number of signatories to the CoP.

The Commission completed its own evaluation of the CoP in May 2020. Its overall conclusion was that the CoP had produced positive results31. The report stressed that the CoP had created a common framework and had improved cooperation between policymakers and the signatories. The main weaknesses it identified were:

- its self-regulatory nature;

- lack of uniformity of implementation (uneven progress in monitoring);

- lack of clarity around its scope and some of the key concepts.

The signatories themselves did not manage to prepare an annual review of the CoP as initially agreed. As the signatories do not have a common representative, coordination is time-consuming and informal, and reaching consensus on how this annual review will take place and who will conduct it has proven difficult.

In September 2020, the Commission presented a staff working document32 taking stock of all evaluations of the CoP to date. It recognised that “it remains difficult to precisely assess the timeliness, comprehensiveness and impact of platforms’ actions”. The Commission has also identified the need for “commonly-shared definitions, clearer procedures, more precise and more comprehensive commitments, as well as transparent key performance indicators (KPIs) and appropriate monitoring”.

Our work confirms that signatories’ reporting varies, depending on their level of commitment and whether they are an online platform or a trade association. In addition, the online platforms’ reports are not always comparable and their length varies considerably.

86This variation among signatories to the CoP also proved to be a problem for setting overall KPIs. These KPIs made it possible to monitor the actions of some signatories, but not all. For example, under the heading “Integrity of services”, the Commission proposed the indicator “Number of posts, images, videos or comments acted against for violation of platform policies on the misuse of automated bots”. This output indicator is relevant for specific online platforms only.

87According to the Commission’s own analysis of the CoP signatories’ reports, the metrics provided so far satisfy only output indicators. For example, platforms report that they have rejected advertisements, or removed a number of accounts or messages that were vectors of disinformation in the context of COVID‑19 (see also Box 1). If this reported information is not put into context (i.e. by comparing it, in time, against baseline data and other relevant information such as the overall creation of accounts), and the Commission cannot verify its accuracy, it is of limited use.

88The assessment of the CoP conducted on behalf of the Commission not only looks at the current state of the reporting but also recommends possible metrics for the future. The document proposes two levels of indicators:

- ‘structural’ indicators for the code as a whole, measuring overall outcomes, the prevalence of disinformation online and the code’s impact in general. These help to monitor, at a general level, whether disinformation is on the rise, stable or declining;

- tailored ‘service-level’ indicators, broken down by pillar, to measure each individual signatory platform’s results in combatting disinformation.

At the time of the audit, the Commission had not provided signatories with any new reporting template or more meaningful new indicators.

89The issues described above show that online platforms are not held accountable for their actions and their role in actively tackling disinformation.

Lack of a coherent media literacy strategy and fragmentation of EU actions dilutes their impact

90Pillar IV of the EU action plan focuses on raising awareness and strengthening societal resilience to disinformation. It aims to improve media literacy actions, such as the 2019 Media Literacy Week, and to support independent media and investigative journalists. It also calls on Member States to rapidly implement the media literacy provisions of the Audio-Visual Media Services Directive and create teams of multi-disciplinary independent fact-checkers in light of the 2019 European elections.

91Media literacy’ refers to skills, knowledge and understanding that allow citizens to use media effectively and safely and equip them with the critical thinking skills needed to exercise judgment, analyse complex realities and distinguish between opinion and fact33. Responsibility for media literacy, which lies at the cross-section of education policy and the EU’s digital agenda, lies with the Member States. The Commission’s role is to foster collaboration and facilitate progress in the area. Disinformation does not respect borders, however, and developing common tools and sharing best practices at EU level are important.

92In order to assess the actions under this pillar, we examined the 2019 EU Media Literacy Week event, and whether there was a well-defined strategy for the various initiatives in this area. We reviewed the Commission’s report on the 2019 European elections34 and assessed 20 projects directly related to media literacy and fighting disinformation.

93The Commission’s report on the 2019 European elections stated that “[while] manipulative efforts recurrently focused on politically sensitive topics and targeted EU audiences ahead of the elections, no large-scale covert interference operation in the 2019 elections has been identified so far”.

Member States do not participate evenly in the EU Media Literacy Week

94European Media Literacy Week is a series of actions to raise awareness about media literacy across the EU (see Box 3). It is unclear how it reflects a coherent EU media literacy strategy, however; although it includes some high-level discussions, it mainly serves to illustrate some specific EU and Member State initiatives. The 2020 edition was to be jointly organised between the Commission and the Council, which could have further stimulated Member State action and participation. However, it was cancelled due to COVID‑19.

Box 3

European Media Literacy Week

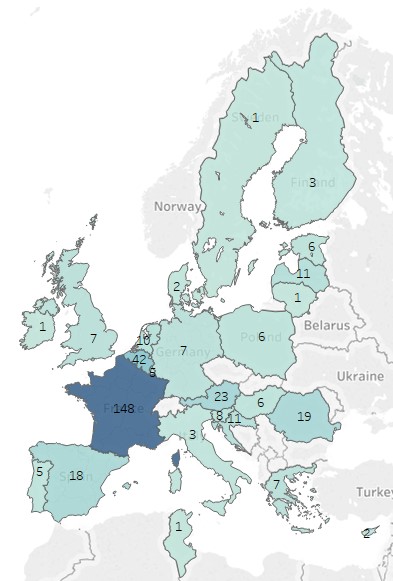

The 2019 Media Literacy Week was one of two specific media literacy actions in the EU action plan. It took place in March 2019 in Brussels and in Member States, and included a high-level conference. Over 320 events were organised at the time, and in total 360 events had been organised up to the end of September 2020.

Nearly half of all events took place in France, with Belgium (mostly Brussels) a distant second. A small number of Member States did not host any events at all – as the geographical distribution of the events shows (see picture opposite). As would be expected, most events took place around the time of the official launch. However, no further statistics are available on the number of people these events reached, their thematic distribution and the extent to which they dealt specifically with disinformation.

Source: ECA, based on Commission data.

There is no overarching media literacy strategy that includes tackling disinformation

95We found there were a multitude of EU and Member State initiatives that addressed media literacy, and a plethora of policy documents. This is also clear from the Council Conclusions on media literacy35, which include an annex with the main policy documents. However, these actions are not coordinated under an overarching strategy for strengthening societal resilience, particularly in media literacy, which would include tackling disinformation. While actions to address Member States’ specific challenges on media literacy are also important in order to achieve local impact, EU support for media literacy lacks the following underlying elements, which would be conducive to its sound financial management:

- a regular update , in cooperation with the Media Literacy Expert Group (MLEG), of the most important media literacy practices and actions in the EU and Member States (the Council of Europe produced such a mapping in 2016, the first of its kind; however, it has not been updated since then36);

- clear objective-setting based on systematic and regular research into media literacy and the impact of media and digital platforms, accompanied by a set of indicators to measure performance;

- the necessary coordination mechanisms to create synergies and avoid overlap between initiatives and actions under, for example, the Audio-Visual Media Services Directive, the digital education action plan, the Creative Europe Programme, the digital competence framework and skills agenda, the recently published European democracy action plan and the Digital Services Act, the media and audiovisual action plan, etc.;

- unified monitoring of EU media literacy initiatives.

For the next multi annual financial framework (2021-2027), according to the Commission, approximately €14 million in EU funding from the Creative Europe programme37 – €2 million per year – has been earmarked to support media literacy. However, as the Council Conclusions on media literacy also state, it will be necessary to develop additional funding sources.

Most projects examined produced tangible results, but many did not demonstrate sufficient scale and reach

97Of the 20 projects we assessed, ten were funded under Horizon 2020, and the other ten were pilot projects and preparatory actions funded by the European Parliament (see table in Annex III).

98The ‘Media Literacy for all’ call for proposals, launched in 2016 by the European Parliament, includes pilot projects and preparatory actions for co-financing innovative start-up ideas from across the EU in the field of media literacy. A pilot project runs for two years, followed by a three-year preparatory action. The Horizon 2020 projects are research and innovation projects covering highly technical aspects of tackling disinformation, such as the use and detection of bots or developing a new generation of content verification tools.

99Our analysis (see Annex III) found tangible results in 12 out of 20 projects. Most positive results were achieved by projects that built on the results of previous projects to produce tools related to fact-checking, or by projects to create teaching and learning material against disinformation (see Box 4).

Box 4

Examples of EU-funded projects achieving positive results

Based on the theoretical research of project 2, which investigated how the information generated by algorithms and other software applications is shared, project 1 produced, as a proof of concept, an interactive web tool designed to help increase transparency around the nature, volume, and engagement with false news on social media, and to serve as a media literacy tool available to the public.

Project 11 set out to create an educational, multilingual (eight EU languages), crowdsourced online platform for teaching and learning about contemporary propaganda. This action was accompanied by sets of contextualised educational resources, and online and offline workshops and seminars for teachers, librarians and media leaders. The project was well set up and produced tangible results, with active participation from six EU countries. Even though the project ended on 1 January 2019, its platform and resources remain active.

However, we identified shortcomings in 10 out of the 20 projects, which concerned mostly their small scale and limited reach. Seven projects did not or are unlikely to reach their intended audience, and the results achieved by three projects were difficult to replicate, which limited their impact. Box 5 presents a number of projects illustrating these issues:

Box 5

Examples of EU-funded projects with limited reach or scale of actions

Project 10 set out to create a system for automatically detecting false information from the way it is spreading through social networks. The project was successful, and an online platform soon recruited the project manager and the people involved in the project, acquiring the technology. This is evidence of a well-identified research project that produced good results. However, its subsequent acquisition by an American online platform has limited the targeted audience it would benefit and does not contribute to the development of an independent EU capability in this sector.

One other project (14) focused on the representation of women in the media. It existed as an online portal presenting news that women journalists and editors found most relevant in their regions while at the same time trying to fact-check news on women’s and minority issues. Although the project reached a considerable audience via Facebook and Twitter with its gender theme, its main output was a website that is no longer available.

Another project (16) was also supposed to develop social skills and critical thinking. It was composed of various heterogeneous parts that focused on creativity, with no clear connection between them and a loose conceptual link to media literacy. For example, children in schools created animation or simple games about cleaning a school gym or protecting a vending machine. The planned activities cannot be easily reproduced.

Overall, there was little evidence of any comparative analysis of project results – especially in terms of what had worked and why. Nor was there much evidence of the Commission coordinating the exchange of best practice and media literacy material across the EU. An evaluation framework is also lacking. Such a framework is critical to the long-term development of societal resilience, as it ensures that lessons learned feed directly into future actions, policy and strategy. Obtaining evidence of the direct impact of media literacy measures is difficult, and efforts are still at an early stage of development38. The Council Conclusions on media literacy also called for the development of systematic criteria and evaluation processes, and a uniform and comparative methodology for Member States’ reporting on the development of media literacy39.

The SOMA and EDMO projects attracted limited interest from media literacy experts and fact-checkers

102As the EU action plan states under pillar IV, independent fact-checkers and researchers play a key role in furthering the understanding of the structures that sustain disinformation and the mechanisms that shape how it is disseminated online. The Commission financed the Social Observatory for Disinformation and Social Media Analysis (SOMA) project, a digital platform with the aim of forming the basis for a European network of fact-checkers. SOMA is funded under Horizon 2020, with an overall budget of nearly €990 000. The project started in November 2018 and is scheduled to end on 30 April 2021.

103Our analysis revealed that SOMA managed to attract only two fact-checkers recognised by the International Fact Checking Network40. At the time of the audit (October 2020), SOMA had 48 registered members. Several of those we contacted admitted to never using the SOMA platform. While the technology behind SOMA has been evaluated positively, the project is still not widely used by the fact-checking community.

104Well before the end of the SOMA project, and without waiting for an evaluation to collect and apply lessons learned, the Commission in June 2020 launched the first phase (worth €2.5 million, running until the end of 2022) of the European Digital Media Observatory (EDMO). It aims to strengthen societal resilience by bringing together fact-checkers, media literacy experts, and academic researchers to understand and analyse disinformation, in collaboration with media organisations, online platforms and media literacy practitioners.

105SOMA and EDMO therefore have partially overlapping objectives, and most contractors are involved in both projects at the same time. The evaluators of SOMA suggested merging the two projects but no formal links between them have yet been established. There is also a risk of overlap in their financing, as both projects are based on and use the same technology and commercial products.

106EDMO has been presented as a holistic solution to tackling many of the societal challenges around disinformation. However, being in its infancy, its visibility among stakeholders is still limited, according to its management. It is too early to judge the effectiveness of EDMO. Nevertheless, given the limited awareness of EDMO among stakeholders, its achievements may not match its overly ambitious goals. Its current focus is on building up the necessary infrastructure, and it will need more resources to succeed in its aims.

107The media literacy experts we interviewed commented that the media literacy community was not feeling sufficiently engaged with EDMO. EDMO’s advisory board features a broad array of expertise from across academia and journalism, reflecting the EU action plan’s key emphasis on strengthening fact-checking and supporting journalism. However, the media literacy community or civil society, who could provide useful links between academia and policy-making are under represented (two out of 19 experts).

Conclusions and recommendations

108We examined whether the EU action plan against disinformation was relevant when drawn up and delivering its intended results. We conclude that the EU action plan was relevant but incomplete, and even though its implementation is broadly on track and there is evidence of positive developments, some results have not been delivered as intended.

109We found that the EU action plan was consistent with experts’ and stakeholders’ views and priorities. It contains relevant, proactive and reactive measures to fight disinformation. However, even though disinformation tactics, actors and technology are constantly evolving, the EU action plan has not been updated since it was presented in 2018. In December 2020, the Commission published the European democracy action plan, which includes actions against disinformation, without clarifying exactly how it relates to the EU action plan against disinformation (see paragraphs 20-24 and 41-42).

110The EU action plan does not include coordination arrangements to ensure that EU responses to disinformation are coherent and proportionate to the type and scale of the threat. Each of the EU action plan’s pillars is under the responsibility of a different Commission Directorate-General or the European External Action Service, without any single body being in charge or having complete oversight of communication activities (see paragraphs 25-31).

111There is no monitoring, evaluation and reporting framework accompanying the EU action plan and the European democracy action plan, which undermines accountability. In particular, the plans include generic objectives that cannot be measured, several actions that are not time-bound and no provisions for evaluation. Only one report on the implementation of the EU action plan has been published, with limited information on performance. Without a comprehensive, regular review and update, it is difficult to ensure that EU efforts in this area are effective and remain relevant. Furthermore, there was no comprehensive information on the funding sources and the estimated costs of the planned actions (see paragraphs 32-40).

Recommendation 1 – Improve the coordination and accountability of EU actions against disinformationThe European Commission should improve the coordination and accountability framework for its actions against disinformation by incorporating:

- clear coordination and communication arrangements between the relevant services implementing the EU actions against disinformation;

- a dedicated monitoring and evaluation framework containing clear, measurable and time-bound actions, as well as indicators to measure performance and evaluation provisions;

- regular reporting on the implementation of the actions, including any necessary updates;

- a summary of the main funding sources and expenditure made in implementing the actions.

Timeframe: end of 2021 for recommendations a) and b) and mid 2023 for recommendations c) and d)

112Under pillar I of the EU action plan the three EEAS strategic communication task forces have improved the EU’s capacity to forecast and respond to disinformation activities and have contributed substantially to effective communication and promoting EU policies in neighbouring countries. The task forces’ mandates do not adequately cover the full range of disinformation actors, including new emerging threats (see paragraphs 45-49).

113Staffing of the task forces largely depends on the secondment of national experts, making it more difficult for the EEAS to manage and retain staff. The StratCom team has not yet met its recruitment targets, and the COVID‑19 crisis has created additional workload. Furthermore, the task forces have no evaluation function to assess their effectiveness and identify areas for improvement (see paragraphs 53-58 and 60).

Recommendation 2 – Improve the operational arrangements of the StratCom division and its task forcesThe EEAS should:

- bring emerging disinformation threats to the Council’s attention. It should then review and clarify the policy objectives to be achieved by strategic communications division and its task forces.

- reach the recruitment targets set in the EU action plan;

- focus its human resources on the most sensitive tasks, such as threat analysis and threat evolution, and outsource less sensitive communication activities where these cannot be done in-house due to staff shortages;

- undertake regular evaluations of the task forces’ operational activities, beyond their communication campaigns.

Timeframe: mid 2022

114EUvsDisinfo has been instrumental in raising awareness about Russian disinformation. However, its placement inside the EEAS raises some questions about its independence and ultimate purpose, as it could be perceived as representing the EU’s official position (see paragraphs 61-64).

115Under pillar II, the EEAS quickly set up the rapid alert system (RAS). We found that the RAS had facilitated information sharing among Member States and EU institutions. However, the RAS has never issued alerts and, consequently, has not been used to coordinate joint attribution and response as initially envisaged. Furthermore, the latest statistics show that activity and engagement in the RAS are driven by a limited number of Member States. There is a downward trend in activity levels and cooperation with online platforms and existing networks is mostly informal. Additionally, there is no protocol establishing cooperation between the RAS and the online platforms (see paragraphs 65-76).

Recommendation 3 – Increase participation in the RAS by Member States and online platformsThe EEAS should:

- request detailed feedback from Member States on the reasons for their low level of engagement and take the necessary operational steps to address them;

- use the RAS as a system for joint responses to disinformation and for coordinated action, as initially intended;

- propose to the online platforms and the Member States a framework for cooperation between the RAS and the online platforms.

Timeframe: mid 2022

116The one action under pillar III is about ensuring continuous monitoring of the code of practice (CoP). It sets out a number of voluntary measures to be taken by online platforms and trade associations representing the advertising sector. With the CoP, the Commission has created a pioneering framework for engagement with online platforms. During the initial stages of the COVID‑19 pandemic, the CoP led the platforms to give greater prominence to information from authoritative sources.

117Our assessment of the CoP and the Commission’s evaluations revealed different reporting from the platforms, depending on their level of commitment. Moreover, the metrics that the platforms are required to report satisfy only output indicators. Platforms do not provide access to data sets, so that the Commission cannot verify the reported information. Consequently, the CoP falls short of its goal to hold online platforms accountable for their actions and their role in actively tackling disinformation (see paragraphs 77-89).

Recommendation 4 – Improve the monitoring and accountability of online platformsBuilding on recent initiatives such as the new European democracy action plan, the Commission should:

- propose additional commitments to the signatories to address weaknesses identified in the evaluations of the code of practice;

- improve the monitoring of the online platforms’ activities to tackle disinformation by setting meaningful KPIs;

- establish a procedure for validating the information provided by online platforms.

Timeframe: end of 2021

118Under pillar IV of the EU action plan, we found there were a multitude of EU and Member State media literacy initiatives, and a plethora of policy documents, which are not organised under an overall media literacy strategy that includes tackling disinformation (see paragraph 95).

119Most activities during the 2019 EU Media Literacy Week took place in just two Member States, which substantially limited the initiative’s awareness-raising potential. Our analysis of a sample of 20 projects addressing disinformation found tangible results in 12 projects. Most positive results were achieved by projects that built on the results of previous projects to produce fact-checking tools or teaching material. The key shortcomings identified in 10 projects relate to the small scale and reach of their activities (see Box 3, paragraphs 94 and 97-101).