Air pollution: Our health still insufficiently protected

About the report Air pollution causes great harm to European citizens’ health. Each year, about 400 000 people die prematurely due to excessive air pollutants such as dust particles, nitrogen dioxide and ozone. For about 30 years, the EU has had clean air legislation that sets limits to the concentrations of pollutants in the air. Nevertheless, bad air is still common today in most of the EU Member States and in numerous European cities. We found that European citizens still breathe harmful air mostly due to weak legislation and poor policy implementation. Our recommendations aim to strengthen the Ambient Air Quality Directive and to promote further effective action by the European Commission and the Member States, including better policy coordination and public information.

Executive summary

Air pollution is the biggest environmental risk to health in the European Union

IAccording to the World Health Organization (WHO), air pollution is the biggest environmental risk to health in the European Union (EU). Each year in the EU, it causes about 400 000 premature deaths, and hundreds of billions of euro in health related external costs. People in urban areas are particularly exposed. Particulate matter, nitrogen dioxide and ground level ozone are the air pollutants responsible for most of these early deaths.

IIThe 2008 Ambient Air Quality Directive is the cornerstone of the EU’s clean air policy, as it sets air quality standards for the concentrations of pollutants in the air we breathe. In recent decades, EU policies have contributed to emission reductions, but air quality has not improved at the same rate and there are still considerable impacts on public health.

What we audited:

IIIIn this audit, we assessed whether EU actions to protect human health from air pollution have been effective. To do this, we examined whether (i) the AAQ Directive was well designed to tackle the health impact of air pollution; (ii) Member States’ effectively implemented the Directive; (iii) the Commission monitored and enforced implementation of the Directive; (iv) air quality was adequately reflected in other EU policies and adequately supported by EU funds; and (v) the public has been well informed on air quality matters.

IVWe concluded that EU action to protect human health from air pollution had not delivered the expected impact. The significant human and economic costs have not yet been reflected in adequate action across the EU.

- The EU’s air quality standards were set almost twenty years ago and some of them are much weaker than WHO guidelines and the level suggested by the latest scientific evidence on human health impacts.

- While air quality has been improving, most Member States still do not comply with the EU’s air quality standards and were not taking enough effective action to sufficiently improve air quality. Air pollution can be underestimated as it might not be monitored in the right places. Air Quality Plans – a key requirement of the Ambient Air Quality Directive – often did not deliver expected results.

- The Commission faces limitations in monitoring Member States’ performance. Subsequent enforcement by the Commission could not ensure that Member States complied with the air quality limits set by the Ambient Air Quality Directive. Despite the Commission taking legal action against many Member States and achieving favourable rulings, Member States continue to frequently breach air quality limits.

- Many EU policies have an impact on air quality, but, given the significant human and economic costs, we consider that some EU policies do not yet sufficiently well reflect the importance of improving air quality. Climate and energy, transport, industry, and agriculture are EU polices with a direct impact on air quality, and choices made to implement them can be detrimental to clean air. We noted that direct EU funding for air quality can provide useful support, but funded projects were not always sufficiently well targeted. We also saw some good projects – particularly some projects supported by the LIFE programme.

- Public awareness and information has a critical role in addressing air pollution, a pressing public health issue. Recently, citizens have been getting more involved in air quality issues and have gone to national Courts, which have ruled in favour of their right to clean air in several Member States. Yet, we found that the Ambient Air Quality Directive protects citizens’ rights to access to justice less explicitly than some other environmental Directives. The information made available to citizens on air quality was sometimes unclear.

What we recommend:

VOur report makes recommendations to the Commission aimed at improving air quality. Our recommendations cover more effective actions which should be taken by the Commission; the update of the Ambient Air Quality Directive; the prioritisation and mainstreaming of air quality policy into other EU policies; and the improvement of public awareness and information.

Introduction

Why air pollution matters

01Air pollution occurs when gases, dust particles and smoke are released into the atmosphere, making it harmful to humans, infrastructure and the environment. The World Health Organization (WHO) classifies air pollution as the biggest environmental risk to health in Europe1. In the EU, air pollution causes more than 1 000 premature deaths on average each day, which is more than 10 times the number killed by road accidents2. Figure 1 shows that lost years of healthy life in some EU Member States are similar to countries often associated with poor quality air, such as China and India. In 2013, the EU Commission estimated the total health related external costs of air pollution at between €330 and €940 billion per year3.

Figure 1

Lost years of healthy life from ambient air pollution per hundred inhabitants

Source: WHO, “Public Health and Environment (PHE): ambient air pollution DALYs attributable to ambient air pollution”, 2012.

People in cities are the most affected

02According to the EEA, in 2015, around one-quarter of Europeans living in urban areas were exposed to air pollutant levels exceeding some EU air quality standards and up to 96 % of EU citizens living in urban areas were exposed to levels of air pollutants considered by the WHO as damaging to health4. Air pollution tends to affect city dwellers more than inhabitants of rural areas because the density of people living in cities means that air pollutants are released on a larger scale (for example, from road transport) and because dispersion is more difficult in cities than in the countryside.

What shortens people’s lives and how?

03The WHO identifies Particulate Matter (PM), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), sulphur dioxide (SO2) and ground-level ozone (O3) as the air pollutants that are most harmful to human health (see Box 1)5. The EEA reported that, in 2014, fine particles (PM2.5) caused about 400 000 premature deaths of EU citizens; NO2 caused 75 000 and O3 caused 13 6006. The EEA warns that air pollution affects people on a daily basis, and that while pollution peaks are its most visible effect, long-term exposure to lower doses poses a greater threat to human health7.

Box 1

Main air pollutants

Particulate matter (PM) comprises solid and liquid particles suspended in the air. These include a wide range of substances, from sea salt and pollens to human carcinogens like Benzo[a]pyrene and Black Carbon. PM is classified as PM10 (coarse particles) and PM2.5 (fine particles)8, depending on its size. In those parts of Europe where household heating still often uses solid fuel, air pollutant emissions (in particular PM) tend to increase when winters are more severe.

Nitrogen dioxide (NO2) is a toxic gas of reddish-brown colour. It is one of the nitrogen oxides (NOX).

Sulphur dioxide (SO2) is a toxic colourless gas with a sharp odour. It is one of the sulphur oxides (SOX).

Ground-level ozone (O3), or tropospheric ozone9, is a colourless gas that is formed in a layer close to the ground by the chemical reaction of pollutants (such as Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) and NOX) in the presence of sunlight.

According to the WHO, heart disease and stroke cause 80 % of premature deaths due to air pollution. Lung diseases including cancer, and other diseases follow10. Figure 2 summarises the main health impacts of the four air pollutants mentioned above.

Figure 2

Main health impacts of PM, NO2, SO2 and O3

Sources: EEA and WHO.

Box 2 explains what factors affect the levels of air pollution and Figure 3 shows the percentages of the air pollutants emissions from each source in the EU.

Box 2

Air quality does not only depend on pollution emissions

It also depends on:

- proximity to the source and altitude at which pollutants are released;

- meteorological conditions, including wind and heat;

- chemical transformations (reactions to sunlight, pollutant interactions);

- geographical conditions (topography).

Air pollution emissions result mostly from human action (e.g. from transport, power stations or factories). They can also result from forest fires, volcanic eruptions and wind erosion.

Figure 3

Sources of air pollutants in the EU11

Source for the data: EEA, “Air quality in Europe — 2017 report”, 2017, p. 22.

What has the EU been doing?

06The EU tackles air pollution by setting (a) concentration limit values of pollutants for the air that people breathe, and (b) standards on pollutants’ emission sources.

07In 1980, Directive 80/779/EC first established EU limits for SO2 concentrations. Other Directives have followed, covering more air pollutants and updating their limit values12. The 2008 Ambient Air Quality Directive (AAQ Directive)13 sets air quality standards (including limit values) for the concentrations of air pollutants with the biggest health impacts (see paragraph 18). It focuses on improving citizens’ health through better quality of the air that people breathe.

08The AAQ Directive requires that Member States define air quality zones within their territory. Member States carry out preliminary air quality assessments in each zone and set networks of fixed measuring stations in polluted areas. The Directive contains criteria both for the location and for the minimum number of sampling points (see paragraph 32)14.

09Member States collect data from their networks and report this to the Commission and the EEA each year (see Box 3). The Commission assesses these data against the EU standards15 of the AAQ Directive. Where concentrations exceed the standards, Member States must produce Air Quality Plans (AQPs) that tackle the problem as soon as possible. The Commission assesses these plans and takes legal action where it considers that Member States fail to comply with the Directive. The Directive imposes public information obligations on the Member States, including alert and information thresholds.

Box 3

Commission and EEA’s roles

The Commission is responsible for assessing compliance and for overseeing the implementation of the Directive.

The EEA is an agency of the European Union that aims to provide sound, independent information on the environment. The EEA’s role is to provide timely, targeted, relevant and reliable information to policymaking agents and the public aiming to support sustainable development.

In addition to setting concentration limits, the EU has legislated to reduce air pollutant emissions from several sectors16.

11The EEA points out that in recent decades European Directives (see Annex I) and Regulations (such as those leading to fuel switching or abatement of inefficient equipment) have contributed to reductions in air pollutant emissions. Between 1990 and 2015, SOX emissions in the EU decreased by 89 % and NOX emissions by 56 %. Since 2000, PM2.5 emissions have decreased by 26 %17 as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4

Air pollutant emission trends since 1990 (since 2000 for PM2.5)

Source: EEA.

According to the WHO and the EEA, this decrease in the total emissions of air pollutants does not automatically translate into similar reductions in air pollutant concentrations18. The EU source legislation does not focus on reducing emissions in places where people suffer most from air pollution or where concentrations are highest (see Figure 5). For example, if car engines emit less, due to stricter EU emission standards, air pollution can still increase if car use increases. Therefore, specific action in populated areas is necessary to reduce concentrations of air pollutants as human exposure, particularly to PM and NO2, remains high.

Figure 5

PM10 and NO2 concentrations in 2015

Source: EEA data and maps.

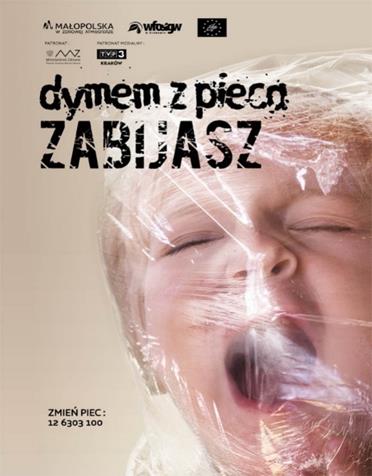

Following earlier strategies, in December 2013, the European Commission published the Clean Air Programme for Europe. This aims to tackle the widespread non-compliance with the EU’s air quality standards and ensure full compliance with existing legislation by 2020. It also sets a pathway for the EU to meet by 2030 the long-term goal of reducing premature mortality due to PM and O3 by 52 % relative to year 2005. The Commission recognised that significant compliance gaps for some pollutants remain, and launched a fitness check in 2017 to examine the performance of the Ambient Air Quality Directive.

Audit scope and approach

14This report assesses whether EU actions to protect human health from air pollution have been effective. We examined whether (i) the AAQ Directive was well designed to tackle the health impact of air pollution; (ii) Member States’ effectively implemented the Directive; (iii) the Commission monitored and enforced implementation of the Directive; (iv) air quality was adequately reflected in other EU policies and adequately supported by EU funds; and (v) the public has been well informed on air quality matters.

15We focused on the provisions of the AAQ Directive related to human health and on the air pollutants with the greatest health impact: PM, NO2, SO2 and O3 (see paragraph 3)19.

16We concentrated on urban areas, as this is where air pollution most affects health (see paragraph 2). We examined how six urban centres in the EU dealt with the problem and used funding from the EU’s Cohesion policy and LIFE programmes (see Box 4)20.

Box 4

Selection of six case studies

In our selection, we aimed for a broad geographical distribution of high pollution hotspots. We also considered the amounts of EU air quality funding received by these Member States. The map shows the main pollutants and their sources in the selected cities as identified by the Member States.

Sources: ECA analysis and Air Quality Plans of the six cities visited.

We covered the period from the adoption of the AAQ Directive in 2008 to March 2018. We examined the policy design and Commission’s monitoring of implementation of the AAQ Directive through reviewing documents, interviewing staff and checking databases at the Commission and the EEA. To examine Member States’ implementation of the Directive and EU-funded air quality projects, we carried out on-the-spot visits, examined project documentation and interviewed local stakeholders (national and local authorities, project beneficiaries, and other civil society stakeholders) in the six selected cities and in the capitals of the respective Member States. For the audit work in Poland, we cooperated with the Supreme Audit Office (NIK)21. We took into account expert advice on the design, implementation and monitoring of the AAQ Directive. We also contributed to an international cooperative audit on air quality by EUROSAI.

Observations

The Directive’s standards are weaker than the evidence on health impacts of air pollution suggests

18The EU standards for health protection set out in the AAQ Directive address both short and long-term health impacts22. They limit the number of times concentrations can exceed short-term (daily and hourly) values; they also require annual averages to be below defined values. The AAQ Directive states that “(…) appropriate objectives [should be] set for ambient air quality taking into account relevant World Health Organisation standards, guidelines and programmes”23.

19However, EU ambient air quality limits are much weaker than the WHO guidelines for PM2.5 and SO2, and weaker for PM10 (annual average) and for ozone. For PM10 (daily value) and NO2, EU standards are aligned with WHO guidelines, and permit some occasions when limits are exceeded. Table 1 provides a comparison of WHO air quality guidelines and EU standards and Box 5 explains the difference between guidelines and standards.

| Pollutant | Period | WHO Guidelines μg/m3 | EU AAQ Directive limit values μg/m3 | No. of times in a year that the EU standards can be exceeded |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NO2 | 1 year | 40 | 40 | - |

| 1 hour | 200 | 200 | 18 | |

| O3 | 8 hours | 100 | 120 | 25 |

| PM10 | 1 year | 20 | 40 | - |

| 24 hours | 50(a) | 50 | 35 | |

| PM2.5 | 1 year | 10 | 25 | - |

| 24 hours | 25 | - | - | |

| SO2 | 24 hours | 20 | 125 | 3 |

| 1 hour | - | 350 | 24 | |

| 10 minutes | 500 | - | - |

(a) The WHO recommends following this guideline as the 99th percentile (3 exceedances).

Sources: WHO Air quality guidelines (2005) and AAQ Directive 2008/50/EC.

Box 5

Guidelines vs standard values

Air quality guidelines are based on scientific evidence of the health effects of air pollution. Standards – which are in most cases legally binding – need to take account of technical feasibility, and the costs and benefits of compliance24. WHO guidance indicates that allowing limits to be exceeded on a certain number of occasions can reduce the cost of compliance25.

The AAQ Directive was the first Directive to set limit values for PM2.5, but not the first to regulate concentrations of PM10, NO2, SO2, and O3. As it did not introduce any changes to the values set by the Directives that it updated26, the limit values for PM10, NO2 and SO2 are now almost 20 years old27, and the target value of O3 is over 15 years old28.

21The EU legislators weakened the Commission’s proposal of 1997 by setting higher limit values or number of times they might be exceeded29. The O3 target value in the AAQ Directive is less strict than in the past30.

22The WHO considers PM2.5 to be the most harmful air pollutant31. WHO guidelines include a short-term value for PM2.5 but the AAQ Directive does not. This means that the EU standard relies only on a yearly average and high and harmful PM2.5 emissions from household heating during the winter are offset by the lower summer levels (see Box 1). The annual limit value set in the AAQ Directive (25μg/m3) is more than the double of the WHO guideline value (10μg/m3). The AAQ Directive introduced the possibility of updating the limit value to 20μg/m3, but the Commission did not do so when it examined the issue in 2013.

23The EU daily limit value for SO2 is over six times the WHO guideline value. Although almost all Member States comply with the EU daily limit (see Figure 6), the EEA points out that in 2015 20 % of the EU urban population was still exposed to concentrations above the WHO’s guideline value32. The general compliance with the undemanding limit values for SO2 in the AAQ Directive means that the Commission is only taking enforcement action against one Member State (Bulgaria, see Annex III).

Figure 6

Compliance with SO2 daily limit value in 2016

Source: European Air Quality Portal data viewer.

Setting very undemanding standards has serious implications for reporting and enforcement actions, notably for SO2 and PM2.5 (see paragraphs 22 to 23). For example, places with SO2 concentrations significantly higher than WHO guideline values remain compliant with the AAQ Directive and, consequently, they are obliged to set up fewer measuring stations, to report data from fewer places and they often give no consideration on tackling SO2 concentrations in their AQPs.

25The Commission assessed the direct costs of complying with their proposal for the AAQ Directive at between €5 and €8 billion, and the monetised health benefits at between €37 to €119 billion per annum in 2020. The Commission concluded that benefits of the air quality policy greatly exceeded implementation costs33.

26In 2013, the WHO carried out a “Review of evidence on health aspects of air pollution”. This recommended the Commission to ensure that the evidence on health effects of air pollutants and the implications for air quality were reviewed regularly. The WHO review found that scientific evidence supported stricter EU limit values for PM10 and PM2.5, and regulating short-term averages (e.g. 24 hours) for PM2.5. This exercise aimed to support the Commission’s 2013 review of EU air quality policies, but did not lead to any change in the original AAQ Directive limit values.

27More recently, several professional medical organisations have called for the EU to take account of the latest scientific evidence in support of stricter standards and a new short-term standard for PM2.534.

Most Member States did not effectively implement the AAQ Directive

28In 2016, 13 Member States breached PM limit values35, 19 NO2 limit values36 and one SO2 limit values37. All 28 EU Member States except Estonia, Ireland, Cyprus, Latvia, Lithuania and Malta were in breach of one or more of these limit values (see Figure 7).

Figure 7

Member States compliance with limit values in 2016

Source: European Commission.

Figure 8 compares the PM and NO2 concentrations in each of the cities we visited, to EU limit values38. Overall, measured air pollutant concentrations have decreased – most significantly for PM10 – but they still exceed at least one of the AAQ Directive limit values in all cities. In particular, there was almost no progress in Krakow (PM) and Sofia (PM2.5) since 2009. In Brussels and Milan, NO2 concentrations changed little between 2012 and 2016 (see Annex II). However, part of the improvements in the measurements may not have resulted from better air quality, as explained in paragraphs 32 and 33.

Figure 8

PM and NO2 maximum concentrations (2009 to 2016)39

Source: European Air Quality Portal data viewer.

and the provisions for measuring air quality offer a degree of flexibility that makes verification difficult

30Getting good measurements on air pollution levels is important because this serves as the trigger for actions by Member States to reduce pollution. Furthermore, accurate and comparable data on pollution are important for the Commission to consider enforcement actions (see paragraph 49).

31For the purposes of the AAQ Directive, Member States measure air quality through a network of monitoring stations containing devices (sampling points) that analyse and measure the levels of several air pollutants40. Many Member States display air quality levels in websites for public information. Member States need to send validated data to the Commission once a year. The Commission then assesses compliance with the Directive. Member States are required to produce Air Quality Plans when the validated data shows that pollution exceeded AAQ Directive limits.

Air quality monitoring station and sampling points (blue devices in the picture on the right)

Source: ECA.

The AAQ Directive sets criteria for the minimum number of the sampling points and for their site locations. However, the site location provisions involve multiple criteria and offer a degree of flexibility which can make verification more difficult. They require Member States to locate sampling points both “where the highest concentrations occur” (with traffic or industrial type stations) and in other areas which are “representative of the general population’s exposure”41 (with background type stations). As a result, Member States do not necessarily measure air quality near major industries or main urban traffic routes. Complying with the Directive may be easier when the number of traffic or industrial stations is low. Box 6 shows that practices vary in the six cities that we visited42.

Box 6

Different practices when siting monitoring stations

Brussels has only two traffic stations, while Stuttgart had eight and Milan had 11 (only six within the city limits, two of which were inside the Low Emission Zone).

The Ostrava air quality zone has significant industrial facilities on its territory, but only one of its 16 monitoring stations is “Industrial”. A similar situation occurs in Krakow, where only one of the city’s six monitoring stations is “Industrial”. Sofia has no “Industrial” monitoring stations, even though power plants and other industrial facilities are located there.

The minimum number of sampling points depends on the population living in each air quality zone. All the cities we visited had more monitoring points than required by the Directive. These extra measurements do not have to be included in the official data reported by the Member States even when they identify high levels of pollution (see Box 7). The AAQ Directive requires that Member States maintain sampling points that have exceeded PM10, but this obligation does not apply to other pollutants (in particular, NO2 and PM2.5)43.

Box 7

High levels of pollution not included in the official data

In Ostrava, Radvanice ZÚ station does not report validated data to the Commission although it exceeded the PM daily limit value 98 times in 2015.

In Brussels, the Arts-Loi station recorded in 2008 a very high NO2 annual average (101 µg/m3). In 2009, the station was closed due to works but when the works were finished (in 2016) the station still did not report official data to the Commission.

In Sofia, construction works caused the relocation of the Orlov Most station in 2014. This station previously recorded the highest number of days of PM10 concentrations exceeding the limit. After its relocation, the frequency of such events measured in Sofia dropped sharply (See Annex II).

Source: ECA analysis.

The AAQ Directive does not require any specific monitoring in problematic border areas. Tackling effectively transboundary pollution requires coordinated action. For example, if Ostrava fuel quality laws are enforced, they may only be effective in improving air quality if neighbouring regions of Poland take action. If not, people will still be able to use cheap, low quality fuel bought across the border. Under Article 25 of the Directive, Member States shall invite the Commission to assist in any cooperation regarding cross-border air pollution. The Member States most affected by transboundary pollution that we visited did not consider the relevant provisions of the Directive helpful and they did not undertake any coordinated actions in their AQPs. They did not request the Commission to intervene.

35In 2017, Member States we visited mostly reported data on time. Timely air quality data is important, both for the Member States to take appropriate actions to reduce air pollution, and for the Commission to act earlier to take enforcement procedures against the Member State. The AAQ Directive requires that Member States provide annual validated data by 30 September of the following year44. However, earlier Directives required Member States to report to the Commission within six months of the measuring period45. Technological developments over recent years (such as e-Reporting) enable earlier reporting.

while Air Quality Plans are not designed as effective monitoring tools

36Breaches of the Directive mean that Member States need to produce Air Quality Plans (AQPs) to deal with the problem (see paragraph 9). Real improvements in air quality depend on Member States implementing quick and effective actions to reduce emissions, using good Air Quality Plans.

AQP measures are frequently poorly targeted

37The AAQ Directive requires that AQPs set out appropriate measures, so that the time air pollution exceeds limits is kept as short as possible. We reviewed the AQPs of the visited cities.

38Based on our analysis of AQPs we identified three main reasons that compromise their effectiveness. These were that the measures in the AQPs:

- were not targeted and could not be implemented quickly for the areas where the highest concentrations were measured;

- could not deliver significant results in the short term because they went beyond the powers of the local authorities responsible for implementing them or because they were designed for the long-term;

- were not supported by cost estimates or were not funded.

Box 8 provides examples of weaknesses in AQPs compromising the goal of reducing air pollution concentrations.

Box 8

Examples compromising AQP results

Diesel vehicles are a significant source of air pollution, particularly NO2 (see paragraph 57). However, measures to reduce the use of private transport near the sites where the highest concentrations are measured were largely absent from the six AQPs we analysed.

In Italy (Milan), the use of electronic systems for monitoring access to the Low Emission Zones requires the previous adoption of national legislation. In Belgium (Brussels), the AQP proposes restricting (pre Euro 5) vehicles in LEZs from 2025. Furthermore, the planned impact of traffic restrictions included in Member States’ AQPs on reducing NO2 concentrations is unreliable as it is not based on real driving conditions.

Replacing inefficient heating devices, often owned by low-income families, is a major challenge for citizens and some Member State authorities. In Poland (Małopolska), the anti-smog resolution restricts the use of solid fuels. The cost of replacing residential heating sources may exceed €1 billion. National funding was not secured.

While the AQPs identified the main pollution sources, they did not always contain specific measures to tackle their emissions. For example, Krakow’s latest AQP contains only limited measures that reduce industrial emissions – which is a major source of NO2 pollution, while Sofia’s AQP does not include any measure that reduces emissions from households – which is a major source of PM pollution (see Box 4).

41AQPs frequently proposed measures that do not have a direct impact on reducing air pollutant concentrations such as administrative simplification measures, evaluations or surveys. We also found that AQPs did not assess the cost effectiveness of the measures.

42Achieving air quality targets sometimes requires difficult political decisions. For example, the use of personal vehicles is a major source of urban air pollution in Brussels, Stuttgart and Milan, and the most effective measures would be to limit their use.

Am Neckartor monitoring station in Stuttgart

Source: ECA.

AQPs privilege quantity over the quality of information

43All the six cities we visited have been producing AQPs for a long time. The plans typically cover four to five year periods. The Air Quality Directive does not require Member States to report on implementation of their AQPs to the Commission, or to update them when new measures are adopted or when progress is visibly insufficient. Member States only need to update their AQPs at the end of the plan’s period, if air quality still does not meet the standards.

44Because of widespread high levels of pollution, Member States prepare a high number of AQPs. The AQPs we examined were lengthy46 and often did not contain all relevant air quality measures planned or taken47. Member States also report more documents containing additional measures when requested by the Commission.

45The production of AQPs is a lengthy process. When Member States send them to the Commission, they usually deal with a breach of an air pollution limit that occurred more than two years earlier48, but provide no information about subsequent progress.

46The above factors combine to make monitoring of Member State actions by the Commission a difficult exercise. This slowed monitoring of the implementation of the Directive.

47The continuing, although decreasing, high levels of pollution (see Figure 4), show that producing AQPs have not been sufficient to ensure compliance with the AAQ Directive and reduce pollution as soon as possible. The European Court of Justice (ECJ) confirmed this in recent rulings (see paragraph 52).

The Commission faces limitations in checking compliance and the enforcement process is slow

48The AAQ Directive requires the Commission to monitor and enforce Member States’ implementation of the Directive. However, Member States do not have to report on implementation of their AQPs, or to update them when they adopt new measures, or when progress is insufficient (see paragraph 43). Some provisions of the Directive are by their nature difficult to verify (such as ensuring that Member States comply with their public information duties; or checking the location of more than four thousand monitoring stations).

49While air pollution limits are frequently exceeded, the Commission identifies the most serious breaches of compliance and starts dialogues with the Member States, until it decides to close the process or concludes that the Member State has failed to put forward sufficiently ambitious and convincing measures. At this stage, the Commission can launch infringement proceedings against the Member State.

50As of January 2018, the Commission had 16 ongoing infringement proceedings due to PM pollution, 13 due to NO2, one due to SO2 and two other infringement proceedings regarding air pollution monitoring (see Annex III).

51We analysed the ongoing infringements processes involving the six cities we visited49. All six Member States applied for the postponement of attainment deadlines under Article 2250. Consequently, the infringement procedure could only start once the Commission decided on these applications for postponement.

52The Commission has on four occasions51 succeeded in obtaining favourable rulings against Member States for exceeding air pollution limits, but that did not require the Member State to take corrective action. As a result, the Commission has redefined its approach and recently won Court cases against Bulgaria (on 5 April 2017) and Poland (on 22 February 2018)52. In its rulings, the ECJ confirmed that merely adopting an AQP to comply with the Directive was not enough, and ruled that Bulgaria and Poland had not fulfilled their obligations to keep the period in which limits were exceeded as short as possible. Figure 9 shows that it took between six and eight years until the Commission referred these cases related to PM10 infringements to the ECJ53. To apply financial penalties, the Commission has to go back to the ECJ and seek a new ruling54. The NO2 infringements started much later and no case has yet been referred to the ECJ. There is no ongoing infringement procedure on ozone55.

Figure 9

Length of the PM10 procedures (in years)

Source: European Commission.

Member States have more than two years to submit their AQPs, after they detect breaches of air quality limits. As subsequent dialogues in the context of infringement procedures between the Member States and the Commission have lasted more than 5 years in some cases, it is very likely that during this period Member States update their AQPs. This requires the Commission to examine the updated AQP. Consequently, it has taken at least 7 years from the moment of the original breach until the Commission refers the case to the ECJ.

54Overall, we found that the lengthy enforcement procedure has not yet ensured compliance with the Directive.

Some EU policies do not sufficiently reflect the importance of air pollution

55Many EU policies have an impact on air pollutants and thus on air quality, particularly climate change, energy, transport and mobility, industry and agriculture.

56The targets in the EU’s 2030 climate and energy framework to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 40 %, to have at least 27 % energy from renewable sources, and to improve energy efficiency by at least 27 %, can all support the reduction of emissions. We reported in a Landscape Review of 2017 that one of the main challenges facing EU action on energy and climate change was the transition of the EU to low carbon energy sources, and that this transition can offer benefits to air quality56.

57Diesel vehicles were a key element for car manufacturers in the EU to comply with their carbon dioxide (CO2) reduction obligations57, as they produce lower CO2 emissions than petrol cars. Technological developments and EURO standards58 have significantly reduced CO2 and PM emissions – but were not as successful in reducing NOX emissions – from such vehicles. It has been known for years59 that real NOX emissions were higher than those produced under test conditions. The “Dieselgate” scandal which came to notice when inspectors in the USA detected suspicious readings in vehicle inspections, highlighted the scale and causes of these discrepancies60. Before Dieselgate, the European Commission had launched work on a more realistic EU test procedure. Yet conformity factors mean that in practice the EURO 6 emission target of 80 mg NOX emissions per km (decided by the EU legislators in 2007 for implementation in 2014) will not have to be met for the Real Driving Emissions test before 202361.

58Fuel taxation supports diesel sales in all Member States except Hungary and the UK62. While purchases of new diesel cars fell after Dieselgate, around 40 % of all cars on the road in the EU are diesel powered63. As road transport, and particularly diesel cars, are a major source of NO2 emissions (see Figure 3), efforts to reduce them are complicated.

59The EU’s climate change policies support biomass as a renewable source of energy64. The Renewable Energy Directive65 required in 2009 that the EU meets at least 20 % of its total energy needs with renewables by 2020. EU funding for biomass projects has since more than doubled66. In our Special Report No 5/2018 on renewable energy for sustainable rural development, we reported that combustion of wood biomass can also lead to higher emissions of certain harmful air pollutants. The EEA has identified similar issues67.

60The use of inefficient solid-fuel boilers or heaters exacerbates the problem of air pollution from local heating. The EU has set standards to improve the efficiency of such devices (the Ecodesign Directive68 with its implementing regulations), but such standards will only come into force for new devices in 2022.

61The Industrial Emissions Directive (IED) is the main EU instrument regulating air pollutant emissions from industrial installations (see Annex I). The Directive allows Member States to set less stringent emission limit values if applying best available techniques (BATs) would lead to “disproportionately higher costs” compared to the environmental benefits. The Directive also allows certain “flexibility instruments” by way of exemption from the limits set for large combustion plants. For example, 15 Member States69 have adopted “Transitional National Plans” which allow higher emission ceilings until 2020; some district heating plants have been granted special derogation until 2023; and other plants do not need to apply BATs if they limit their operations and close by 2024.

62Agriculture accounts for 94 % of ammonia (NH3) emissions in the EU70. Ammonia is a precursor of PM. The EEA indicates that NH3 emissions from agriculture contribute to episodes of high PM concentrations experienced across certain regions of Europe that breach AAQ Directive PM10 limit values71.

63Although EU policies regulate agricultural practices72, progress on reducing air pollutants from agriculture has been very slow73 and since 2012, NH3 emissions have even increased74. The EEA notes that despite the existence of technically and economically viable measures such as agronomic, livestock or energy measures, they have yet to be adopted at the scale and intensity necessary to deliver significant emission reductions75.

and EU funding is useful but not always targeted

64We examined how the LIFE programme, the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) and the Cohesion Fund (CF) supported actions to improve air quality in the six Member States that we visited.

LIFE Programme

65The EU supports air quality through its LIFE Programme76. We reviewed six LIFE projects related to air quality in Germany, Italy and Poland77. These included the project “LIFE Legal Actions – Legal Actions on Clean Air” that supported civil society stakeholders, who could, for example, launch Court cases seeking improvements in air quality78 (see paragraph 73). The use of the LIFE budget to support civil action at Member State level is a novel, cost effective, rapid route to encourage Member States and cities to support air quality policy.

66Since 2014, Integrated Projects of the LIFE Programme support the planning of air quality policy through the use of other available EU funds. For example, an integrated project supported implementation of the Malopolska AQP in Poland. It included an information campaign, addressed to the citizens of the region, raising awareness on the danger of smoke from solid fuel boilers (see poster in Figure 10 that says: “fumes from your boiler kill”).

Figure 10

Example of a public information poster of Malopolska LIFE programme

Source: Marshall Office of Malopolska Region, Poland.

Cohesion policy funding

67The ERDF and the CF provide most EU funding for air quality. While some actions explicitly aim to reduce air pollution, many that target other objectives (e.g. clean urban transport or energy efficiency) may also benefit air quality.

68Dedicated funding79 available increased from €880 million in the 2007 - 2013 programming period to €1.8 billion in the 2014-2020 period but this amounted to less than 1 % of total cohesion policy funding. Three of the Member States we visited used these funds, but only in Poland did the respective amounts increase significantly between the previous and current programming periods. In the Czech Republic, funding remained stable, while in Bulgaria it fell significantly (see Table 2).

| (in million euro) | 2007/2013 | 2014/2020 | Variation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bulgaria | 120 | 50 | -58 % |

| Czech Republic | 446 | 454 | +2 % |

| Poland(1) | 140 | 368 | +163 % |

(1) Amounts from the Operational Programme Infrastructure and Environment and the Regional Operational Programme Malopolska.

Source: European Commission and Member States.

69We found cases where Member States did not prioritise this funding on projects that target the main sources and pollutants identified in the air quality zones we visited (see Box 4). For example, no projects target emission reductions from domestic heating in Sofia (a major source of PM emissions)80.

70We also found that EU funded projects were not sufficiently well supported by Member States’ plans to improve air quality. For example, a boiler replacement scheme in Krakow is being implemented without the national authorities restricting the availability of inefficient boilers and low quality coal.

71We also found good examples of EU-funded projects that were well targeted and contributed directly to reductions in local emissions, as identified in Member States’ AQPs. This was the case, for example, of the replacement of old diesel buses by buses running on compressed natural gas (CNG); and the boiler replacement schemes in Ostrava. There were also projects to modernise inefficient household heating systems (in Krakow), and public transport (in Krakow and Sofia). Until 2013, there were projects to reduce industrial emissions in Krakow and Ostrava (a major source of PM and NOX emissions)81.

Industrial plant financed in Ostrava

Source: ECA.

Citizen action has a growing role

72The EEA regards public information as an essential element to address air pollution and reduce its harmful impacts82 and the WHO underlines that “improving transparency and sharing quality information widely in cities will further empower people to participate productively in decision-making processes”83. The AAQ Directive sets alert thresholds for SO2, NO2 and O3, but not for PM84, and requires Member States to provide detailed information to the public85. Citizens can thus play a key role in monitoring the Member States’ implementation of the AAQ Directive, in particular when results imply difficult political choices. Local action is important, but requires public awareness: only if citizens are well informed can they be involved in the policy and take action, where appropriate, including changing their own behaviour.

73The increasing importance of the citizens’ actions is shown by the recent Court cases launched by citizens and NGOs against their national authorities. In the Czech Republic, Germany, France, Italy and the UK, national courts have ruled in favour of citizens’ right to clean air and required the Member States concerned to take further action to tackle air pollution.

but public rights to access to justice are not explicitly protected by the Directive

74The right to justice, to environmental information and to public participation in environmental decision-making, is established by the Aarhus Convention, to which the EU and its 28 Member States are parties86. We found that other environmental Directives contain explicit provisions that guarantee the rights of members of the public to justice, while the AAQ Directive does not87.

75National laws vary considerably and civil society organisations have identified obstacles to citizens when seeking access to justice in some Member States.

and air quality information is sometimes unclear

76We checked the information made available online by public authorities to the citizens of the six cities visited. To do this we examined air quality indices, information on the health impacts of air pollution, the availability of real time air quality data, and other tools.

77Air quality indices are tools that can give understandable information to citizens. Five of the six cities we visited use such indices. We found that Member States, regions and cities define air quality indices differently, which results in different assessments for the same air quality (see, for example, Table 3). As the damage to human health is no different for the same air pollution, independent of the location, different classifications for the same quality of air compromise the credibility of the information provided.

| Index based on PM hourly/daily value | 0 | 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 80 | 90 | 100 | 140 | 180 | 200+ | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EEA | good | fair | moderate | poor | very poor | |||||||||||||||

| Brussels | excellent | very good | good | fairly good | moderate | poor | very poor | bad | very bad | horrible | ||||||||||

| Milan | good | fair | mediocre | bad | horrible | |||||||||||||||

| Krakow | very good | good | moderate | sufficient | bad | very bad | ||||||||||||||

| Ostrava | very good | good | fair | suitable | poor | very poor | ||||||||||||||

| Stuttgart | very good | good | satisfactory | sufficient | bad | very bad | ||||||||||||||

| Sofia | good | fair | sufficient | bad | very bad | |||||||||||||||

Source: EEA and cities websites.

78As Member States had not agreed on a common index, the EEA in cooperation with the European Commission recently launched an index for the whole territory of the EU (see Figure 11 below). By consulting the EEA index, citizens can compare air quality across Europe in real time. This is not the same as assessing compliance with the EU standards (which requires longer data series).

Figure 11

EEA’s air quality index for 20.3.2018

Source: EEA.

The AAQ Directive requires that Member States inform the public on the possible health effects of air pollution. The online information provided by public authorities regarding the health impacts of air pollution and the measures citizens can take to mitigate risks was sometimes scarce and hard to find. This is all the more important if one considers that EU standards underestimate the risks posed by poor air quality (see paragraphs 19 to 27).

80Member States are required to report real-time air quality data to the Commission88. At the time of our audit, twenty-five Member States did so89. Of the six cities we visited, four displayed real time data on their websites90. These cities used a variety of tools to keep the public informed. Table 4 shows some of the good practices they used to inform citizens.

| Spatial maps using modelling | Brussels, Milan, Ostrava |

| Notification during pollution peaks (SMS or email etc.) | Brussels, Krakow, Ostrava |

| Smartphone apps | Ostrava, Krakow |

| Display panels in public spaces (streets, metro) | Krakow, Sofia |

| Downloadable data series for analysis | Brussels, Stuttgart, Milan, Krakow |

| Early PM alert system based on weather forecasts | Stuttgart |

While most of the cities we visited produced air quality indices and real time air quality data, and some had adopted other good practices, we concluded that the quality of public information was not as clear or useful as the information made available by some other European cities91.

Conclusions and recommendations

82According to the World Health Organization, air pollution is the biggest environmental risk to health in the EU, and the EEA estimates that it causes about 400 000 premature deaths each year, with people in urban areas particularly exposed. Particulate matter, nitrogen dioxide, sulphur dioxide and ground level ozone are the most harmful of these air pollutants. The 2008 Ambient Air Quality (AAQ) Directive is the cornerstone of the EU’s clean air policy, as this sets concentration limits for pollutants in the air we breathe.

83We concluded that EU action to protect human health from air pollution had not delivered the expected impact. The significant human and economic costs have not yet been reflected in adequate action across the EU.

84Although air quality has benefited from emission reductions, citizens’ health is still heavily affected by air pollution. Several of the EU’s air quality standards are weaker than the evidence on health impacts of air pollution suggests. Member States often do not comply with these standards, and they have not taken enough effective action to improve air quality. The Commission’s monitoring and subsequent enforcement did not lead to effective change. We found that some EU policies do not yet sufficiently well reflect the importance of improving air quality, while noting that EU funding provides useful support. Citizens can play a key role in monitoring the Member States implementation of the AAQ Directive, as seen in successful Court action in several Member States, and public awareness and information was growing. The following paragraphs detail our main conclusions and respective recommendations.

85The AAQ Directive is based on air quality standards that are by now 15 to 20 years old. Some of these standards are much weaker than the World Health Organization guidelines. Furthermore, the standards allow limits to be exceeded frequently and do not include any short-term standard for PM2.5, a very harmful air pollutant (see Table 1 and paragraphs 18 to 26). Health professionals support stricter standards in the EU (see paragraph 27). Setting weak standards does not provide the right framework for protecting human health. It means that some locations with poor air quality are compliant with EU law.

86While the situation is improving, most Member States still do not comply with the EU’s air quality standards (paragraphs 28 to 29).

87Concerning the measurement of air quality, we found that there were insufficient guarantees that air quality was being measured by the Member States in the right locations. Due to imprecise criteria in the Directive, the Member States did not necessarily measure concentrations near main urban roads or big industrial sites (see paragraphs 32 to 34), which were still major sources of pollution. We note that the deadline for Member States to report data to the Commission as set by the AAQ Directive is less strict than in earlier Directives (paragraph 35).

88We found that Member States were not taking enough effective action to improve air quality as quickly as possible. Overall, the quality of Member States’ Air Quality Plans was insufficient and included poorly targeted measures. They often suffered from weak governance (for example, a lack of coordination between national and local authorities); were not costed or funded; and did not provide information about the real impact of measures taken on air quality. The AAQ Directive does not oblige Member States to inform the Commission on the performance of their Plans. The insufficient progress in improvement of air quality illustrates a need for more effective action (see paragraphs 36 to 47).

89The Commission faces limitations in its monitoring of Member States’ performance. Member States are not required to report on implementation of their Air Quality Plans. Some provisions of the Directive are difficult to verify, and the Commission receives hundreds of Air Quality Plans and extensive data sets to review. We found that the Commission has pursued Member States at the European Court of Justice when it considered that they were in serious breach of the Directive (see paragraphs 48 to 50). However, these enforcement measures are lengthy, and to date, despite obtaining several favourable judgements (paragraphs 51 to 54), air quality limits continue to be frequently breached.

Recommendation 1 – More effective action by the Commission

To take more effective action to improve air quality, the Commission should:

- Share best practice from Member States who have successfully reflected the requirements of the AAQ Directive in their Air Quality Plans, including on issues such as information relevant for monitoring purposes; targeted, budgeted and short-term measures to improve air quality; and planned reductions in concentration levels at specific locations.

- Actively manage each stage of the infringement procedure to shorten the period before cases are resolved or submitted to the European Court of Justice.

- Assist the Member States most affected by intra EU transboundary air pollution in their cooperation and joint activities, including introducing relevant measures in their Air Quality Plans.

Target implementation date: 2020.

90Our conclusions relating to air quality standards, actions by Member States to improve air quality, and subsequent monitoring and enforcement, and public awareness and information (see below) lead us to recommend to the Commission to consider an ambitious update of the Ambient Air Quality Directive, which remains a significant instrument to make our air cleaner.

Recommendation 2 – Ambitious update of the AAQ Directive

The Commission should address the following issues when preparing its proposal to the legislator:

- Considering updating the EU limit and target values (for PM, SO2 and O3), in line with the latest WHO guidance; reducing the number of times that concentrations can exceed standards (for PM, NO2, SO2 and O3); and setting a short-term limit value for PM2.5 and alert thresholds for PM.

- Improvements to the Air Quality Plans, notably by making them result oriented; and by requiring yearly reporting of their implementation; and their update whenever necessary. The number of Air Quality Plans by air quality zone should be limited.

- The precision of the requirements for locating industrial and traffic measuring stations, to better measure the highest exposure of the population to air pollution; and to set a minimum number of measurement stations per type (traffic, industrial or background).

- The possibility for the Commission to require additional monitoring points where it considers this is necessary to better measure air pollution.

- Advancing the date (currently 30 September of year n+1) to at least 30 June n+1, to report validated data, and explicitly requiring Member States to provide up-to-date (real time) data.

- Explicit provisions that ensure citizens’ rights to access justice.

Target implementation date: 2022.

91Many EU policies have an impact on air quality. Given the significant human and economic costs of air pollution, we consider that the importance of this problem is not yet sufficiently well reflected in some EU policies. For example, climate and energy, transport, industry, and agriculture policies contain elements that can be detrimental to clean air (see paragraphs 55 to 63).

92Less than 1 % of EU cohesion policy funding is directly allocated to air quality measures. However other cohesion policy actions can indirectly benefit air quality. We found that EU funded projects were not sufficiently well targeted and supported by Member States’ plans to improve air quality, but we also identified several good examples. We saw that LIFE projects helped citizens take action seeking to improve air quality in their Member States and better target EU funded actions (paragraphs 64 to 71).

Recommendation 3 – Prioritising and mainstreaming air quality into EU policies

To further mainstream air quality into EU policies, the Commission should produce assessments of:

- other EU policies that contain elements that can be detrimental to clean air, and take action to better align these policies with the air quality objective.

- the actual use of relevant funding available in support of EU air quality objectives to tackle air pollution emissions, notably PM, NOX and SOX.

Target implementation date: 2022.

93Public awareness and information has a critical role in addressing air pollution. Recently, citizens have been getting more involved in air quality issues and national Courts have ruled in favour of citizens’ right to clean air in several Member States (paragraphs 72 and 73). Yet, we found that, compared to other environmental Directives the AAQ Directive contains no specific provisions to guarantee the rights of citizens to access to justice (see paragraph 74). We also saw that the quality of information made available to citizens on air quality was sometimes unclear (see paragraphs 76 to 81).

Recommendation 4 – Improving public awareness and information

To improve the quality of information for citizens, the Commission should:

- Identify and compile, with the help of health professionals, the most critical information that the Commission and Member States authorities should make available to citizens (including health impacts and behavioural recommendations).

- Support the Member States to adopt best practices to communicate with and involve citizens in air quality matters.

- Publish rankings of air quality zones with the best and worst progress achieved each year and share the best practices applied by the most successful locations.

- Develop an online tool that allows citizens to report on air quality violations and provide feedback to the Commission on issues related to Member States’ actions on air quality.

- Support the Member States to develop user-friendly tools for the access of general public to air quality information and monitoring (for example, smartphone apps and/or social media dedicated pages).

- Together with the Member States, seek an agreement on harmonising air quality indices.

Target implementation date: 2022.

This Report was adopted by Chamber I, headed by Mr Nikolaos A. Milionis, Member of the Court of Auditors, in Luxembourg at its meeting of 11 July 2018.

For the Court of Auditors

Klaus-Heiner LEHNE

President

Annexes

Annex I

Main Directives setting limits on sources of emissions

The EU source specific legislation most relevant to air pollutants emissions include the National Emission Ceilings (NEC) Directive that targets overall emission reductions, the Industrial Emissions Directive (IED) and the Directive for medium-sized combustion power plants, for industrial sources; the Regulation on Euro 5 and Euro 6 vehicle emissions and other Directives for transport92; and the Ecodesign Directive and its implementing regulations, for household heating and cooling.

The NEC Directive

While the AAQ Directive sets common limits for pollution where it occurs, the NEC Directive deals with emissions at national level. It requires that each Member State commit on reducing its emissions of SO2, NOX, NMVOC, NH3 and PM2.5 (but not explicitly PM10 emissions) as of 2020, and for 2030 and beyond.

The Directive, which was adopted in 2001 and revised in 2016, reflects the international air pollution reduction commitments assumed by the EU and its Member States to the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE)93. The EU and its 28 Member States report their emission inventories to this UN Commission.

In 2010, a target date set by the 2001 NEC Directive, 12 Member States had failed to meet at least one of their ceiling targets.

The IED94 and the Directive for medium-sized combustion plants95

These Directives aim to achieve a high level of protection for human health and the environment in the EU by reducing harmful industrial emissions. They set binding limits for NOX, SO2 and dust (which includes PM)96.

Under the Industrial Emissions Directives, around 50 000 industrial installations need to get an operating permit granted by the EU’s Member States national authorities and to apply Best Available Techniques (BATs).

The IED applies to large industries in different sectors: energy industries, production and processing of metals, mineral industry, chemical industry, waste management, and other. It contains specific provisions on combustion of fuels in installations with a total rated thermal input of 50 megawatts (MW) or more that apply to around 3 500 plants of which 370 are very large biomass and solid-fired plants with a thermal output of more than 300 MW operating in the EU.

In July 2017, the Commission adopted an Implementing Decision based on new reference document updating BATs for large combustion plants97. The permits for these plants must be updated in line with BAT conclusions and associated pollutant emission levels by 2021.

The Directive for medium-sized combustion plants applies, with a few exceptions, to combustion plants with a rated thermal input equal to or greater than 1 MW and less than 50 MW, irrespective of the type of fuel they use.

Annex II

Maximum concentration values in the six air quality zones (Data as of 13 December 2017)98

| NO2 annual means (max. 40µg/m3) |

PM2.5 annual means (max. 25µg/m3) |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AQ zone: | Brussels | Krakow | Milan | Ostrava | Sofia | Stuttgart | AQ zone: | Brussels | Krakow | Milan | Ostrava | Sofia | Stuttgart | |

| 2009 | 51.57 | 70.02 | 80.55 | 46.96 | 57.51 | 111.91 | 2009 | 23.64 | 39.24 | 34.40 | 38.84 | 23.84 | 25.62 | |

| 2010 | 53.75 | 70.36 | 73.36 | 50.90 | 48.52 | 99.92 | 2010 | 22.44 | 61.13 | 33.38 | 50.21 | 31.14 | 27.29 | |

| 2011 | 49.97 | 73.07 | 79.42 | 46.41 | 51.76 | 97.33 | 2011 | 25.05 | 54.98 | 39.01 | 41.45 | 44.64 | 23.94 | |

| 2012 | 48.13 | 71.45 | 67.34 | 43.10 | 45.33 | 91.27 | 2012 | 22.76 | 46.20 | 34.00 | 42.22 | 28.00 | 20.74 | |

| 2013 | 62.62 | 68.00 | 57.48 | 41.43 | 39.30 | 89.03 | 2013 | 20.38 | 43.48 | 30.99 | 35.76 | 30.46 | 20.77 | |

| 2014 | 47.38 | 61.50 | 59.34 | 39.18 | 31.92 | 88.60 | 2014 | 16.99 | 45.02 | 26.19 | 36.18 | 28.71 | 17.67 | |

| 2015 | 45.17 | 63.13 | 75.27 | 39.95 | 32.69 | 87.23 | 2015 | 16.28 | 43.85 | 31.90 | 33.04 | 24.57 | 17.50 | |

| 2016 | 47.72 | 59.28 | 67.00 | 39.07 | 33.15 | 81.60 | 2016 | 17.20 | 37.88 | 28.53 | 31.63 | 22.14 | 17.80 | |

| PM10 number of days above 50µg/m3 (max. 35) |

PM10 annual means (max. 40µg/m3) |

|||||||||||||

| AQ zone: | Brussels | Krakow | Milan | Ostrava | Sofia | Stuttgart | AQ zone: | Brussels | Krakow | Milan | Ostrava | Sofia | Stuttgart | |

| 2009 | 66 | 168 | 116 | 135 | 161 | 112 | 2009 | 36.50 | 60.34 | 46.81 | 53.11 | 65.44 | 45.16 | |

| 2010 | 49 | 148 | 90 | 159 | 134 | 104 | 2010 | 32.90 | 65.95 | 40.72 | 66.00 | 53.84 | 44.07 | |

| 2011 | 88 | 204 | 132 | 123 | 134 | 89 | 2011 | 39.40 | 76.63 | 50.22 | 52.54 | 70.48 | 39.76 | |

| 2012 | 57 | 132 | 111 | 110 | 108 | 80 | 2012 | 34.30 | 65.85 | 46.11 | 56.27 | 53.89 | 37.56 | |

| 2013 | 58 | 158 | 100 | 102 | 109 | 91 | 2013 | 33.50 | 59.67 | 42.40 | 47.00 | 52.43 | 40.07 | |

| 2014 | 33 | 188 | 88 | 116 | 104 | 64 | 2014 | 31.99 | 63.90 | 37.06 | 48.04 | 52.96 | 37.52 | |

| 2015 | 19 | 200 | 102 | 84 | 72 | 72 | 2015 | 27.20 | 67.81 | 41.58 | 41.57 | 41.78 | 37.08 | |

| 2016 | 15 | 164 | 73 | 80 | 71 | 63 | 2016 | 24.69 | 56.67 | 38.12 | 39.71 | 40.00 | 37.56 | |

Annex III

Infringement procedures related to the Ambient Air Quality Directive in April 2018

| EU Member State | Infringement procedure status | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PM10 | NO2 | SO2 | Monitoring | |

| Belgium | ECJ (on hold) | LFN | - | - |

| Bulgaria | RUL | - | RO | |

| Czech Republic | RO | LFN | - | - |

| Denmark | - | LFN | - | - |

| Germany | RO | RO | - | - |

| Estonia | - | - | - | - |

| Ireland | - | - | - | - |

| Greece | RO | - | - | - |

| Spain | RO | RO | - | - |

| France | RO | RO | - | - |

| Croatia | - | - | - | - |

| Italy | RO | RO | - | - |

| Cyprus | - | - | - | - |

| Latvia | RO | - | - | - |

| Lithuania | - | - | - | - |

| Luxembourg | - | LFN | - | - |

| Hungary | RO | LFN | - | - |

| Malta | - | - | - | - |

| Netherlands | - | - | - | - |

| Austria | - | LFN | - | - |

| Poland | RUL | LFN | - | - |

| Portugal | RO | LFN | - | - |

| Romania | RO | - | - | LFN |

| Slovenia | LFN | - | - | - |

| Slovakia | RO | - | - | LFN |

| Finland | - | - | - | - |

| Sweden | RO | - | - | - |

| United Kingdom | - | RO | - | - |

Legend:

LFN = Letter of formal notice sent

RO = Reasoned opinion sent

ECJ = Case referred to the ECJ

RUL = ECJ ruled the case

Infringement procedures start with the Commission issuing to a Member State a letter of formal notice (LFN), which defines the scope of the case. If the Commission does not consider the Member State’s arguments to be reasonable and convincing, it sends another letter (a Reasoned Opinion (RO)), which is the last step before the case is referred to the European Court of Justice.

Glossary and abbreviations

AAQ Directive: Ambient Air Quality Directive (Directive 2008/50/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 May 2008 on ambient air quality and cleaner air for Europe (OJ L 152, 11.6.2008, p. 1)).

Ammonia (NH3): Colourless, pungent gas.

AQP: Air Quality Plan

BATs: ‘Best available techniques’ means the most effective and advanced stage in the development of activities and their methods of operation which indicates the practical suitability of particular techniques for providing the basis for emission limit values and other permit conditions designed to prevent and, where that is not practicable, to reduce emissions and the impact on the environment as a whole.

Benzo[a]pyrene (BaP): BaP is a solid emitted as a result of the incomplete combustion of fossil fuels and biofuels. Its main sources are domestic heating (in particular, wood and coal burning), electricity generation in power plants, waste incineration, coke production and steel production.

Black carbon: Black carbon is a constituent of PM2.5, formed from incomplete fuel combustion, with the main sources being transport and domestic heating.

Carbon dioxide (CO2): CO2 is a colourless gas which is the most significant greenhouse gas in the earth’s atmosphere. It is mostly released into the atmosphere from the burning of fossil fuels.

Compressed Natural Gas (CNG): CNG is natural gas stored at a high pressure which can be used instead of gasoline, propane or diesel fuel.

DALYs Dispersion conditions: Disability Adjusted Life Years Dispersion conditions indicate the ability of the atmosphere to dilute airborne pollutants.

ECJ: European Court of Justice

EEA: European Environment Agency

Fitness check: Comprehensive policy evaluation aimed at assessing whether the regulatory framework for a particular policy sector is ‘fit for purpose’.

IED: Industrial Emissions Directive (Directive 2010/75/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 November 2010 on industrial emissions (integrated pollution prevention and control) (OJ L 334, 17.12.2010, p. 17) (Recast)).

Low Emission Zone (LEZ): A LEZ is a defined area where access by some polluting vehicles is restricted or deterred with the aim of improving air quality.

NEC Directive: National Emission Ceilings Directive (Directive (EU) 2016/2284 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 December 2016 on the reduction of national emissions of certain atmospheric pollutants, amending Directive 2003/35/EC and repealing Directive 2001/81/EC (OJ L 344, 17.12.2016, p. 1)).

Nitrogen dioxide (NO2): Toxic reddish-brown gas. A nitrogen oxide (NOX).

Non Methane Volatile Organic Compounds (NMVOC): NMVOC is a designation that includes many different chemical compounds, such as benzene, ethanol, formaldehyde, cyclohexane, or acetone.

Ozone (Ground-level ozone, O3): Colourless gas with a sharp odour that is not directly emitted into the atmosphere, but is formed by the chemical reaction of pollutants in the presence of sunlight.

Premature deaths: Deaths that occur before a person reaches the standard life expectancy for a country and gender.

Particulate matter (PM): Solid and liquid particles suspended in the air. Depending on its size, PM is classified as coarse particles (PM10) and fine particles (PM2.5).

Sulphur dioxide (SO2): Toxic colourless gas. A sulphur oxide (SOX).

Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs): VOCs are organic chemicals that easily evaporate.

WHO: World Health Organization

µg/m3: Micrograms per cubic meter (unit of measure of the concentration of a pollutant in the air).

Endnotes

1 WHO, “Ambient Air Pollution: A global assessment of exposure and burden of disease”, 2016, p. 15 and EEA, “Air quality in Europe — 2017 report”, 2017, p. 12.

2 European Commission press release of 16 November 2017.

3 SWD(2013) 532 final of 18.12.2013 ”Executive Summary of the Impact Assessment”, p. 2.

4 EEA, “Outdoor air quality in urban areas”, 2017.

5 WHO webpage and WHO, “Economic cost of the health impact of air pollution in Europe”, 2015, p. 3.

6 The EEA explains that the impacts for each pollutant may not be added. See EEA, “Air quality in Europe — 2017 report”, 2017, p. 56.

7 EEA, “Air quality in Europe — 2017 report”, 2017, p. 55 and Table 10.1., and EEA, “Cleaner air benefits human health and climate change”, 2017.

8 PM10 are particulate matter with a diameter up to 10 µm and PM2.5 are particulate matter with a diameter of 2.5 µm or less.

9 This ozone does not contribute to the ozone layer in the upper atmosphere (stratospheric ozone).

10 EEA, “Air quality in Europe — 2013 report”, 2013, p. 17. See also IARC, “Outdoor air pollution a leading environmental cause of cancer deaths”, 2013. The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) is an intergovernmental agency of the WHO.

11 Emission of air pollutants are quantified in terms of NOX and SOX while air pollutants concentrations focus on NO2 and SO2, the most harmful of these oxides.

12 E.g. Directives 82/884/EEC, 85/203/EEC, 92/72/EEC, 96/62/EC (Framework Directive), 1999/30/EC, 2000/69/EC, 2002/3/EC and 2004/107/EC.

13 Directive 2008/50/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 May 2008 on ambient air quality and cleaner air for Europe (OJ L 152, 11.6.2008, p. 1).

14 Sampling points are devices that collect and analyse the concentration of air pollutants in the air. Normally, one fixed measuring station (monitoring station) contains several sampling points.

15 The designation “standard value” covers the binding limit values set for PM, NO2 and SO2 as well as the target value set for O3, which is to be attained where possible over a given period.

16 The relevant Union source-based air pollution control legislative acts can be found on DG Environment's webpage.

17 EEA, “Emissions of the main air pollutants in Europe”, 2017.

18 This is due to complex factors such as the chemistry of the different pollutants in the atmosphere, or the long-distance transport of air pollutants in the atmosphere. See WHO, “Economic cost of the health impact of air pollution in Europe”, 2015, p. 7. See also EEA, SOER 2015 “European briefings: Air pollution”, 2015 and EEA, “Air pollution: Air pollution harms human health and the environment”, 2008.

19 The AAQ Directive focuses only in ambient air quality; therefore indoor air quality is not part of our audit scope. The Directive also includes provisions and emission limits to protect vegetation, as well as regulating lead, benzene and carbon monoxide concentrations. These were not included in our audit, as their overall effect on levels of premature deaths is low. The audit scope also excluded natural sources of air pollution.

20 The audit did not cover projects funded by EU research programmes, and rural development measures, due to their lack of impact on urban areas.

21 The objective of the cooperation was to share knowledge, expertise and ideas when preparing the audit programmes. It included the exchange of views and audit-related documents. A team composed of auditors representing both institutions participated in the ECA audit mission to Poland.

22 Exposure to air pollution for a few hours or days (short-term exposure) causes acute health symptoms, and exposure over months or years (long-term exposure) is linked to chronic health issues. See EEA, “Air quality in Europe — 2017 report”, 2017, p. 50.

23 See AAQ Directive preamble, paragraph 2.

24 WHO, “Air quality guidelines – Global update 2005”, p. 7.

25 WHO, “Guidance for setting air quality standards”, 1997, Annex 3.

26 The AAQ Directive merged Directives 96/62/EC, 1999/30/EC (1st daughter Directive), 2000/69/EC (2nd daughter Directive) and 2002/3/EC (3rd daughter Directive).

27 They were set in 1999 by Council Directive 1999/30/EC of 22 April 1999 relating to limit values for sulphur dioxide, nitrogen dioxide and oxides of nitrogen, particulate matter and lead in ambient air (OJ L 163, 29.6.1999, p. 41).

28 They were set in 2002 by Directive 2002/3/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 12 February 2002 relating to ozone in ambient air (OJ L 67, 9.3.2002, p. 14).

29 For example, for the PM10 annual limit value, the Commission proposed 30μg/m3, and the AAQ Directive value is 40μg/m3. For the NO2 hourly limit value, the Commission proposed that it could be exceeded eight times per year, and the AAQ Directive allows 18 times.

30 Directive 92/72/EEC set a threshold of 110μg/m3 but Directive 2002/3/EC sets the current target value at 120μg/m3 over a daily eight-hour mean, with 25 exceedances allowed.

32 EEA, “Air quality in Europe — 2017 report”, 2017, p. 9.

33 SEC(2005) 1133 of 29 September 2005 “Impact Assessment annex to the Communication on Thematic Strategy on Air Pollution and the Directive on “Ambient Air Quality and Cleaner Air for Europe”, p. 21.

34 See for example, the contribution by the European Respiratory Society to the Commission’s Fitness Check of the EU Ambient Air Quality Directives, or a recommendation from the Agence nationale de sécurité sanitaire de l’alimentation, de l’environnement et du travail.

35 Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Germany, Spain, France, Croatia, Italy, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia and Sweden. Greece did not report all data required for 2016.

36 Belgium, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Denmark, Germany, Spain, France, Croatia, Italy, Luxembourg, Hungary, Netherlands, Austria, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Finland, Sweden and the United Kingdom. Greece did not report all data required for 2016.

37 Bulgaria.

38 Regarding SO2, all cities we visited complied with EU limit values; regarding Ozone, target values were mostly complied with.

39 The values are the highest measurements registered in each year. For Sofia, the data series covers the period 2010 to 2016 for PM2.5. SO2 and O3 are not presented here as concentrations mostly respected the EU standards in the six visited cities.

40 Including the pollutants covered by our audit (PM, NO2, SO2 and O3).

41 Section B.1. of Annex III of the AAQ Directive.

42 Information based on the 2015 official data reporting to the EEA.

43 See Annex V of the AAQ Directive.

44 Article 27 of the AAQ Directive.

45 Directives 80/779/EEC; 82/884/EEC and 85/203/EEC.

46 The AQPs we analysed were on average well over 200 pages long.

47 For example, in Brussels, several documents contain air quality-related measures: the Plan Régional Air-Climat-Énergie, the COBRACE, the Plan Régional de la Mobilité (IRIS2), and the Plan portant sur les dépassements observés pour les concentrations de NO2. In Milan, regional agreements, such as the Po Valley agreement, complement the Lombardia Region’s AQP.

48 The AAQ Directive states that AQPs shall be communicated to the Commission “without delay, but no later than two years after the end of the year the first exceedance was observed” (see Article 23).

49 All the cities have ongoing infringement procedures for both PM10 and NO2. The exception is Sofia, which has an open infringement only for PM10.