Methodology

Rationale, ambition and scope

Working through communities of practice (CoP) has never been more encouraged in organisations than it is now. Better gathering, sharing and using of data, information and knowledge in public organisations such as the European Commission are essential to deliver integrated policy work and overcome silo mentalities. This is highlighted explicitly in European Commission President von der Leyen’s work guidelines stipulating transparency and the ambition to become a digitally transformed, user-focused and data-driven administration.

Communities of practice stimulate cross-organisation collaboration and knowledge sharing. These communities are ‘groups of people who share a concern or a passion for something they do and learn how to do it better as they interact regularly’ (Lave and Wenger, 1991 and 1996). The idea of connecting people through their practice both within and outside organisations has been around as long as people have been part of organisations. The increasing interest in communities of practice in organisations could be attributed to the useful perspective they provide on explicit and tacit knowledge, learning and development within a field of practice as being key to improving performance. Resilient organisations invest in the learning and development of their people and the organisation as a whole (Webber, 2016).

The idea of the playbook came about from extensive research into the internal and external communities managed by the European Commission’s staff. A first assessment of about 20 internal communities in the Commission was undertaken at the end of 2018 to understand the current status of communities of practice and to provide a framework for continued improvement.

The framework that was developed–the Communities of Practice Success Wheel–features eight success factors for communities to thrive and succeed. This framework was used to create the methodology to set up, run and evaluate communities of practice in the European Commission. This methodology can be applied in any organisation, assisting them in developing communities, networks and other formal or informal structures that require collaboration and cooperation between various stakeholders who need to work together with a common purpose and vision.

In the second communities assessment carried out in 2019/2020, which resulted in a research report and this playbook, we intended to look beyond the previously assessed communities. The scope of this assessment was twofold: (1) to explore, listen to and learn from existing communities at different stages in their life cycle and (2) to take these lessons learnt and integrate them into a revised framework that would build on community managers’ capacity. There were three guiding questions that led this endeavour.

- What brings communities together and lets them thrive? This stipulated a review and adaptation of the previous community of practice success factors and framework.

- What are the challenges that communities face? This question was aimed at identifying barriers to community success and facilitators of change.

- How can we support communities in their life cycle? Based on the insights gained from the previous two questions, this question guided the assembly of a capacity-building package tailored to the communities’ needs, including the development of this playbook.

Overall, this simplification and support exercise took stock of the present community ecosystem within the European Commission and moved from the proposed streamlined general methodology towards developing a more concrete and action-based capacity-building framework for communities.

This capacity-building package proposes to embrace three main overarching areas that are highlighted in the revised Communities of Practice Success Wheel methodology:

- co-ownership – participatory decision-making culture and community governance;

- convening – integrating and facilitating offline and online interactions (a) synchronously between internal and external stakeholders;

- collaboration and cooperation – concrete productivity, user experience and stakeholder engagement guidance around community vision, purpose and objectives.

This playbook is part and parcel of this capacity-building framework. It is intended to empower everybody interested in running communities of practice to understand and apply the most important facets that enable communities to thrive.

In Chapter 3 of this playbook, each section describes a different success facet that is important for enabling a community to thrive. Each facet has its own challenges and processes that we recommend you go through (e.g. what is the role of governance in the running of a community (of practice)?).

As such, this playbook can be used as a point of reference whenever your community faces questions on how to work towards a goal. This guiding framework allows you to focus on being more productive and creative, knowing you are moving in the right direction owing to the extensive research and exchange of experiences that fed into this report.

Methodology on which this playbook is based:

Understand

Two-stage survey (selection and quantification)

-

Exploratory survey November/December 2019 (all European

Commission employees, random encounter ‘in real life’, EU survey

online; face-to-face interviews and multiple choice/open online

survey)

Proof-of-concept based on existing success wheel facets: objectives, sponsorship, leadership, boundary-spanning, risk-free environment, community management, tools and user experience -

In-depth survey January-March 2020 (sampled communities through

initial exploration according to: frequency of mentionings,

maturity, variation in host, bottom-up/top-down impetus,

open/closed membership; open/multiple choice EU survey)

Revised-concept based on refined success wheel facets: shared vision, participation and engagement, community and knowledge, trust and confidence, communication

Define Strategy

Discussion and coaching sessions around second survey responses (specification and qualification)

- Communities’ inner workings February/March2020: illustrations, behaviours and routine interactions, key results, goals and general community ambitions, needs for support

- Thematic analysis of answers

Help and Support

Capacity-building package

- Co-ownership

- Convening

- Collaboration and Cooperation

| 2018 Communities of Practice Success Wheel report | 2019/2020 Communities of practice review report | |

|---|---|---|

| Community identification | Nascent support/steering interest | European Commission-wide exploratory survey, most frequently mentioned |

| Maturity | Mostly nascen | Mixed |

| Host variation (communityreach, boundary-spanning) | Mostly Joint Research Centre | Whole European Commission |

| Community management need (bottom-up/ top-down) | Top-down emphasis | Balanced |

| Membership | Mostly formal | Mixed (informal added) |

As just outlined, the ambition of this review exercise was to broaden the scope of the communities consulted to create a more diverse experience landscape that better covers the various modi operandi, challenges and good practices of communities of practice in the Commission.

Therefore, first, an exploratory survey (including both random offline encounters in various office buildings of the European Commission and an online survey) was conducted in November/December 2019 to map, select and qualify communities that were beyond the scope of those covered in the previous report. The aim was to explore and acknowledge the rich variety of community types and aims present in the Commission.

In a second step, the communities that were convenience sampled through this initial screening were subjected to an in-depth survey covering the reviewed success facets based on the conversations held as part of the exploratory survey. In this step, a quantitative survey and qualitative follow-up interviews were undertaken to combine insights from both realms, each enriching the other. In total, this playbook is based on 37 in-depth survey entries split over 22 identified communities of practice and knowledge centres, as well as six additional entries through the Collaboration Hub–the community of collaboration practitioners in the European Commission.

| CASE SELECTION SCOPE | COMMUNITY OF PRACTICE | NETWORK | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Governance formality | Strong | Mixed | Weak |

| Official sponsorship | High | Mixed | Low |

| Knowledge retention and circulation | Governed and explicit | Mixed | Non-governed and implicit |

| Community management need (bottom-up/ top-down) | Top-down emphasis | Balanced | Balanced |

| Membership | Mostly formal | Mixed (informal added) | European Commission-wide exploratory survey, most frequently mentioned |

The community universe

The outlined methodology let us explore a volatile community universe in the European Commission. This universe sets the scene for the playbook and is point of departure for the described observations.

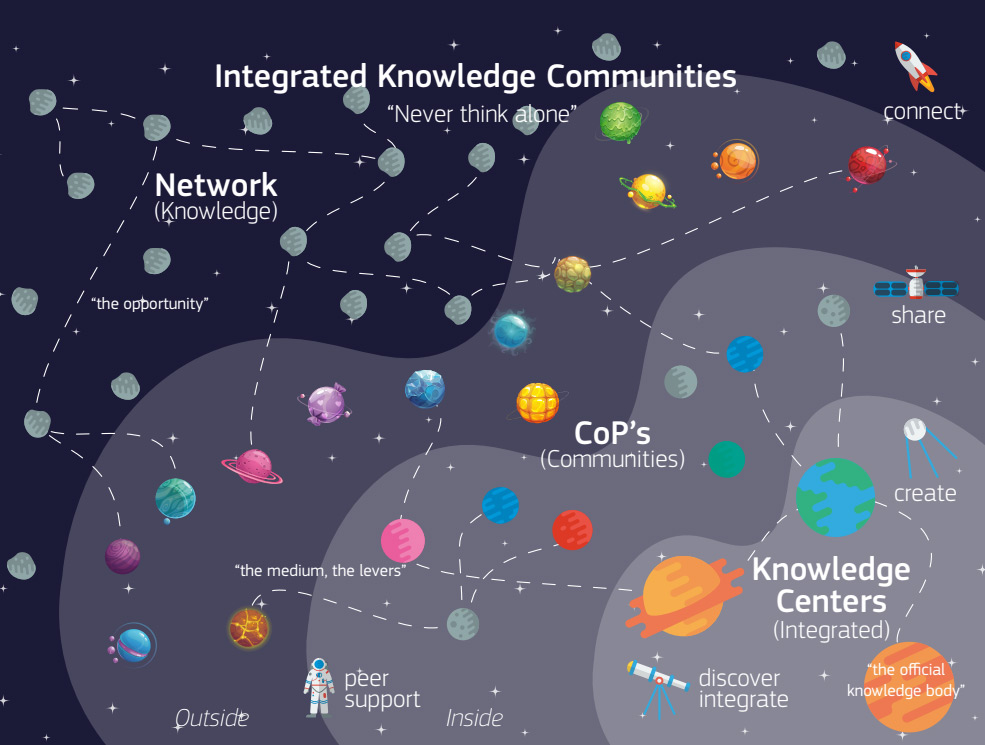

So how does the EC community universe look like? The interstellar systemor universe of (knowledge) communities-within and around the European Commission (EC) is highly diverse in its levels of governance and sponsorship, practices and actions, as well as collaboration opportunities.

In this universe, the stellar vectors (the practices and actions) help to navigate between and connect the elements of the interstellar system with the aim of seeking and integrating knowledge across internal and external communities. This system is made up of planets (knowledge centres, namely European Commission official knowledge bodies), intergalactic stars (communities of practice, namely European Commission knowledge mediums that convey knowledge among stakeholders) and intergalactic satellites (namely (non-European Commission) networks that provide knowledge-sharing opportunities).

All of those planets, intergalactic stars and satellites navigate the galaxy nebula–the abundance of unstructured information and creative collaboration opportunities–to implement their visions and stimulate innovation.

In this diverse and volatile knowledge and collaboration universe of the Commission, there is a multiplicity of knowledge centres, communities (of practice) and network constellations, each with particular interaction and stakeholder patterns. In particular, knowledge centres, communities (of practice) and networks have different roles and working modes:

- communities (of practice) act as the bridge between networks and knowledge centres, and identify and disseminate relevant, applicable knowledge;

- knowledge centres serve to structure, synthesise and underpin this knowledge in an accessible, formalised and expert manner;

- network offer moderated opportunities for both communities (of practice) and knowledge centres to explore new knowledge angles.

In this regard, the convening of boundary-spanning and stakeholder-mapping exercises across knowledge centres, communities (of practice) and networks remains a challenge. As such, collaboration opportunities and knowledge retention and circulation incentives should be created to stimulate the growth and continuity of communities.

Community hurdles and emerging success conditions

Using the methodology outlined above, we surveyed communities, focusing on the following five emerging success conditions–or Communities of Practice Success Wheel facets–built around managing, steering, building, and driving communities (of practice):

(1) shared vision, (2) participation and engagement, (3) community knowledge retention and circulation, (4) trust, confidence and the sense of community, and (5) inclusive communication.

From this survey, six champions (constituting 16.2 % of all surveyed communities)–self-reporting to be doing at least well across all of those facets– and eight struggling communities of practice (constituting 21.6 % of all surveyed communities)–self-reporting to be not doing well in at least one of those facets–emerged.

As a cautious note stemming from these insights, the European Commission environment remains one in which community interactions are bound by colleague, unit or working group silos as well as by (time) resource, recognition, and digital literacy restraints. Informal de facto communities (of place or circumstance) prevail over more formal community types (of practice, knowledge and work) in this volatile and diverse knowledge ecosystem. In the European Commission ecosystem, communities of interest and action have the potential to cut across this divide and to serve as motivational anchors for curiosity and engagement.

Nevertheless, the community of practice collaboration experience in the Commission is overall rated as good, but room for improvement is mentioned frequently.

On the one hand, the passive push roles of communities (of practice) are rated as working fine, namely the following roles:

- amplifying–helping to understand important but little known information;

- curating–organising and managing important information;

- convening–bringing together different individuals or groups.

On the other hand, the proactive pull roles of communities (of practice) are rated as needing improvements, namely the following roles:

- investing and providing–offering a means to give members the resources they need;

- community building–promoting and sustaining values/standards among relevant stakeholders;

- learning and facilitation–helping communities to work more efficiently and effectively.

This playbook takes note of those areas of struggle and provides guidance across these areas. The more in-detail discussion of each of these areas in Chapter 3 identifies specific angles from which to tackle these issues.

- Shared vision

- A core group serving as the ‘governing body’ is paramount–community managers need to work with a core group and for this they need to ‘loosen ownership’ from their side and cultivate and make changes to work towards co-ownership.

- Constantly adapting and aligning the community’s vision, purpose and objectives in a community feedback loop is essential to keep track of progress and keep a community thriving..

- Engaging in boundary-spanning practices is crucial for a community to succeed in its projects. Stakeholder and audience mappings and consultations are important, as are network expansions and professional exchanges. However, these are currently limited in reach.

- Participation and engagement

- A. There is maturity in the way communities convene offline, but this is not true of how they convene online. A seamless combination of both is seen as a challenge by most.

- The more concrete results and deliverables that stem from a community are, the better its vitality is rated (i.e. when its functioning is perceived as better and engagement is higher). However, there is no consensus about how regular community interactions should be for good community vitality (i.e. ad hoc interactions are as valuable as recurring scheduled ones).

- Bridging formal and informal interests and action ambitions is one way of growing curiosity in engaging in community interactions; leading by example and support by management are other important motivators.

- Community knowledge retention and circulation

- Knowledge retention and work applicability is shallow, often without consistent digital participation or coordination. Knowledge pooling and spawning of new ideas are, however, perceived as strong advantages of communities of practice.

- Community management is often perceived as cumbersome and lacking in resources (time/recognition). More concrete guidelines for collaboration, cooperation, coordination, connection and communication are needed.

- Clear role and expectation definitions are needed for community managers (and their peers) to delineate action ambitions and clarify structures.

- Trust, confidence and the sense of community

- Management engagement through leading by example and official sponsorship are driving motivational forces for communities of practice.

- Peer familiarity and exchange between members; transparent, inclusive and diverse membership; and participatory decision-making procedures, as well as perceived community reliability, are paramount in building trust.

- Feeding and guiding organically grown community structures supports the perception of an informal and welcoming community atmosphere and therefore a trusted ‘we are in this together’ environment.

- Inclusive communication

- Communities of practice are valued for their open information sharing and for the breaking down of communication barriers among stakeholders.

- Available communication and productivity platforms/tools lack user-friendliness and communities of practice lack resources to exploit their potential both offline and online; thus, community awareness and overall networked stakeholder engagement levels remain low.

- Timely and democratic information sharing across internal and external stakeholders creates trust and engagement and drives the community of practices’ impact factor.