Comparative report

Chapter 8. A focus on digital and sustainability competences concerns learners of all ages

EU-level target: ‘The share of low-achieving eight-graders in computer and information literacy should be less than 15%, by 2030.’

8.1. Member States are trying to keep up with an accelerated digital transition

All of education and training sectors, from early childhood education through to adult learning, have a role to play in addressing the latest competence requirements. Today, being digitally competent is needed to participate in democratic life, work and lifelong learning. Yet in 2021, 46% of the EU’s adults (aged 16-74) and 29% of young people (aged 16-24) were assumed to have an insufficient level of digital skills204. In a technology-driven society where these skills are a general requirement in daily life and across most occupations and sectors, all EU citizens should have the right to acquire basic digital skills205.

To support Member States’ education and training systems in adapting sustainably and effectively to the digital age, the 2021-27 Digital Education Action Plan sets out two priority areas: (1) fostering the development of a high-performing digital education ecosystem and (2) improving digital skills and competences for the digital transformation.

The COVID-19 pandemic expedited the digital transition, but also drew attention to pre-existing digital skills gaps and exposed new emerging inequalities in the EU. With the digital transformation accelerating, it is essential that education and training systems adjust accordingly. Acknowledging the need to equip young people at an early stage with the skills required to be prepared for the digital age, an ambitious EU-level target has been set to reduce underachievement in digital skills206.

Before to the pandemic, more than one in three students on average in Member States participating in the International Computer and Information Literacy Study (ICILS) performed below the threshold for underachievement. Moreover, as depicted in Figure 29, the ICILS showed evidence of a gender gap in favour of girls in average performance, with a higher share of underachieving boys207. The gender gap is consistent across all proficiency levels in ICILS, except for the highest level208. Despite outperforming boys during compulsory education, relatively few women chose to pursue studies and careers in ICT related fields (see Chapter 5).

Despite outperforming boys in digital skills during compulsory education, relatively few women choose to pursue studies and careers in ICT related fields.

Figure 29. Boys are more likely to underachieve in digital skills than girls

Most Member States209 start compulsory teaching of digital competence at school in primary education210. In 13 Member States, compulsory teaching of digital competence already starts in the first grade211. At this level, the most common approach is to teach digital competence as a cross-curricular subject212. However, it is common for different approaches to co-exist within the same education system. This is also seen in lower secondary education, where the general tendency is to teach digital competence as a compulsory separate subject while many education systems allow for more than one approach.

Although most education systems dictate specific learning outcomes for digital competence213, its assessment in national tests is still uncommon in primary and lower secondary education. Only three education systems (France, Malta and Austria) assess students’ digital competences through specific national tests related to individual student achievement214. In Denmark and France, digital competence is assessed through non-specific national tests, albeit only in lower secondary education. The remaining systems rely on sample-based tests215, do not test digital competences through national tests216, or do not organise national tests in any competence area217.

A key enabling factor for effective digital education and training concerns teachers and trainers who are confident and skilled in using digital technology to support their teaching and adapted pedagogy (Box 23). Before the COVID-19 pandemic, only 37.5% of lower secondary teachers in the EU felt that they were well or very well prepared to use digital technologies for teaching218. Currently, only 15 education systems include teacher-specific digital competences for all teacher profiles as a mandatory component in the curricula of initial teacher education for primary and lower secondary education219. In another three systems (Latvia, Luxembourg and Malta), digital competences are only compulsory for some teacher profiles.

Box 23. Digital skills and the importance of more equitable teacher allocation

Data from TALIS 2018 show that pre-service teacher education and training is a major driver of teachers’ adoption of digital technology for their teaching activities. Teachers can only integrate technology into their teaching if they themselves acquire basic digital skills and are competent enough to tailor technology use to their own teaching. However, having qualified teachers is only part of the equation. If they are unequally distributed across schools, this could lead to achievement gaps widening.

Effective teachers do not necessarily work in the schools that need them the most, which can give rise to socio-economic inequalities in student performance. This is one of the findings from a 2022 OECD report. Moreover, as mentioned in Box 1 at the start of this report, early evidence suggests that learning losses due to the COVID-19 pandemic were more prominent among disadvantaged students than those from more affluent backgrounds. Unequal access to good quality digital infrastructure, equipment, and teachers who were trained in and feel capable of using ICT are likely determinants.

Top-level requirements to appoint a digital school coordinator220 and establish a school digital plan221 are not common across Member States. Actions in these areas are often left to the discretion of school leaders, which implies that practices vary and not every school benefits from such actions. Similarly, criteria related to digital education in external school evaluation are not widespread. In the 23 Member States where external school evaluation is a requirement222, only 13 have specific criteria related to digital education223.

8.2. Adult learning will be needed to reach the Digital Decade objectives

Looking beyond compulsory education, this section addresses digital skills of the adult population224. In 2021, 54% of 16-74 year-olds reported having at least basic digital skills, men (56%) more frequently than women (52%)225. This is some way off the EU’s ambitions for the Digital Decade, with at least 80% of the population reporting basic digital skills by 2030226. Figure 30 shows that the Netherlands (79%), Finland (79%) and Ireland (70%) are the top performers in the EU. Seven Member States have yet to reach 50%227.

Figure 30. Not a single Member State reaches the EU-level target of at least 80% of 16-74 year-olds reporting basic digital skills

Comparing the digital skills level of the general population to that of young people, there is evidence of an age gap in digital skills at EU level. At 16 to 19 years, the approximate age in the latter stages of upper secondary education, the share reporting to have at least basic digital skills was 69% in 2021, 15 percentage points higher than the general population. In the 20-24 age bracket, when many enter higher education for the first time, the share increases to 73%228. Mirroring the findings of the test-based assessment of digital skills in ICILS, 72% of 16-24 year-old women report to have at least basic digital skills, compared to 70% of 16-24 year-old men229.

Box 24. Structured Dialogue with Member States on digital education and skills

The Structured Dialogue with Member States on digital education and skills delivers on Action 1 of the 2021-27 Digital Education Action Plan, and aims to increase the political visibility and commitments on digital education and skills. The Structured Dialogue took place throughout 2022 in the form of bilateral and EU-level discussions with the Member States. It brought together different strands of policy into an integrated approach, seeking to make the most of the synergies between different policy fields – education, digitalisation, labour and finance. The dialogue also benefited from the involvement of the private sector, social partners and civil society.

The dialogue allowed Member State authorities and other participants to share experiences, best practices and success stories, while drawing lessons from each other's less successful initiatives. The outcomes of the dialogue will feed into future actions at EU level on digital education and skills, including the upcoming proposals for Council Recommendations on enabling factors for digital education and on improving the way digital skills are provided in education and training programmes.

As younger cohorts age, there will be a natural increase in the overall digital skill levels of the general population, as implied by Figure 31. However, this increase by itself would not be sufficient to achieve the ambitions of the Digital Decade. There are also other notable gaps that need to be addressed, such as a prominent urban-rural divide230 and a pronounced disadvantage among migrants231.

Figure 31. There is a strong cohort effect in the perceived level of digital skills among 16-74 year-olds

Increasing adult learning (Chapter 6) is paramount in order to close the digital skills gap. Unfortunately, the fact that adult learning is less prevalent among people with lower levels of education does not bode well for the digital transition, as it is these people who will most need such upskilling. Indeed, there is a strong link between educational attainment and individuals’ perceived level of digital skills232. At EU level, adults with a low level of education (32%) are at a clear disadvantage compared to those with a medium level (50%) and high level (79%) of education.

8.3. Gender and socio-economic gaps are replicated in sustainability competence areas

Education and training can help achieve an environmentally sustainable, circular and climate-neutral world233. Supporting the green transition is one of the key objectives of the Recovery and Resilience Plans and EU-level policy coordination is now being coordinated through several initiatives234. Sustainability is high on young people’s minds: a Eurobarometer from May 2022 suggests that poverty and inequality, as well as protecting the environment and fighting climate change are the top priorities among today’s young people (Section 7.3)235.

Learners need to draw on several interlinked competences to live, work and act in a sustainable way. Learning for the green transition and sustainable development requires whole-institution approaches, reviewing the curricula, programmes and learning environments236. On the bright side, one of the positive effects of the COVID-19 pandemic is its potential to transform education. For instance, it appears to have opened up space for re-designing curricula and strategies in teaching sustainability in higher education institutions237. The 2022 European Strategy for Universities supports the higher education sector in adopting whole-institution approaches to achieving the green transition and sustainable development.

Box 25. Sustainability competences according to GreenComp

The Commission has developed a European sustainability competence reference framework – GreenComp. It defines sustainability as ‘prioritising the needs of all life forms and of the planet by ensuring that human activity does not exceed planetary boundaries’. Sustainability competences are defined as those that empower ‘learners to embody sustainability values, and embrace complex systems, in order to take or request action that restores and maintains ecosystem health and enhances justice, generating visions for sustainable futures’.

The framework focuses on developing sustainability knowledge, skills and attitudes for learners so they can think, plan and act with sustainability in mind. GreenComp consists of 12 competences organised into four areas: (1) embodying sustainability values (valuing sustainability, supporting fairness and promoting nature); (2) embracing complexity in sustainability (systems thinking, critical thinking and problem framing); (3) envisioning sustainable futures (futures literacy, adaptability and exploratory thinking); and (4) acting for sustainability (political agency, collective action and individual initiative).

GreenComp can serve a wide range of purposes, including curricula review, design of teacher education programmes, policy development, certification, assessment, and monitoring and evaluation.

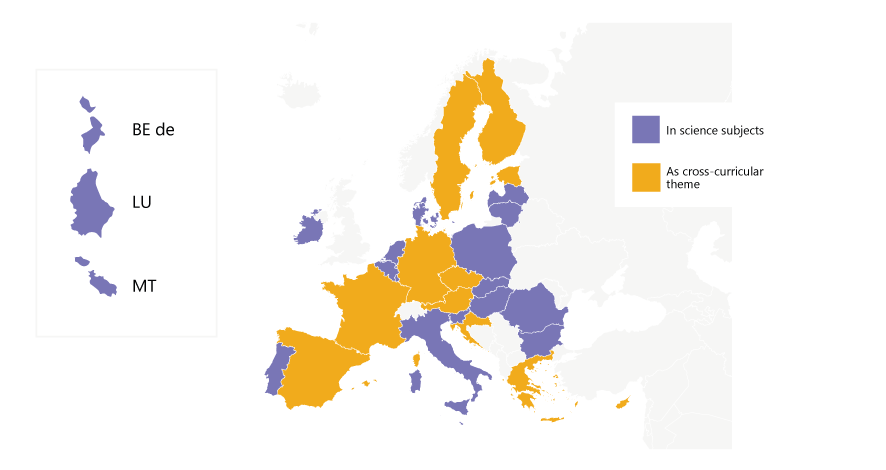

In school education, environmental sustainability topics form a compulsory part of curricula238. In primary education, children often study nature and the need to take care for the environment in the integrated science subject, or they discuss it in the learning areas covering social and environmental aspects. In lower secondary education, learning about environmental sustainability topics takes place in biology, geography, physics and chemistry lessons. Environmental sustainability topics are included in science subjects in all Member States. In addition to that, they are covered as a cross-curricular theme in just under half of the Member States (Figure 32).

Figure 32. Environmental sustainability is a cross-curricular theme in just under half of the Member States

Source: Eurydice 2022.

Note: the indicator covers primary and lower secondary education.

Furthermore, evidence shows that strong gender and socio-economic disparities permeate environmental knowledge and attitudes. According to a 2022 report by the Commission and the OECD239, students from disadvantaged socio-economic backgrounds are less likely to care about the environment or to be aware about environmental problems than their peers from advantaged socio-economic backgrounds. They also have lower levels of achievement in science and engage less in pro-environmental behaviour (Figure 33).

Figure 33. Engagement in environmental protection activities is more prevalent among young people from advantaged socio-economic backgrounds in several Member States

Whereas boys seem more aware of environmental problems such as nuclear waste, the increased greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, use of genetically modified organisms and the consequences of clearing forests for other land use, girls reported higher levels of awareness of water shortage, air pollution and extinction of plants and animals240. When looking at science content areas, boys performed better in physical, earth and science areas, and girls performed better in biology. These results seem to mirror gender stereotypes in STEM study choice (Section 5.2), with women more likely to pursue degrees in ‘biology and related sciences’ (a subfield of the broader ‘natural sciences, mathematics and statistics’ field) than in other STEM fields.

In a nutshell

The promotion of digital and sustainability competences can benefit from them being mainstreamed in compulsory education as cross-curricular subjects. It will also benefit from the boosting of teachers’ confidence and skills. Yet ensuring a basic proficiency in digital and sustainability competences has particular implications for adult learning, making sure that learners who already left the formal education and training systems do not miss out on the opportunities provided by an accelerating twin transition. Moreover, it should be emphasised that these competence domains are marked by the same inequities that permeate the entirety of education and training. For instance, boys are more likely to underachieve in digital skills than girls, and engagement in environmental protection activities is more prevalent among young people from advantaged socio-economic backgrounds in several Member States.

Notes

-

204.Combined percentages for the categories ‘low’, ‘narrow’, ‘limited’ and ‘no skills’ from the Digital Skills Indicator 2.0. This is a composite indicator capturing self-reported internet or software usage (age 16 to 74) in five specific areas (information and data literacy; communication and collaboration; digital content creation; safety; and problem solving). It is assumed that individuals who have carried out certain activities have the corresponding skills. Due to a revision of the survey methodology prior to the 2021 data collection, results are not comparable over time. Monitor Toolbox

-

205.Combined percentages for the categories ‘low’, ‘narrow’, ‘limited’ and ‘no skills’ from the Digital Skills Indicator 2.0. This is a composite indicator capturing self-reported internet or software usage (age 16 to 74) in five specific areas (information and data literacy; communication and collaboration; digital content creation; safety; and problem solving). It is assumed that individuals who have carried out certain activities have the corresponding skills. Due to a revision of the survey methodology prior to the 2021 data collection, results are not comparable over time. Monitor Toolbox

-

206.Data to measure the progress made towards reaching the target stem from the International Computer and Information Literacy Study (ICILS), which is conducted every 5 years by the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA). The study targets students in their eighth year of schooling and uses computer-based assessments to test students’ competence in computer and information literacy. The most recent results are from 2018, and the next cycle is scheduled for 2023 with results due to be released in late 2024.

-

207.See also a 2021 IEA Compass Brief and a 2019 Commission policy note.

-

208.There was either no difference or a slight difference in favour of girls in the participating Member States. In percentage points, the largest differences were found in Finland (1.5) and France (1.4), followed by Germany (0.3) and Luxembourg (0.3). In Denmark (0.0) and Portugal (0.0) there were no discernible differences. Monitor Toolbox

-

209.Policy levers captured in this section are based on a 2022 trial data collection by the Eurydice network. The selected indicators cover primary education and (general) lower secondary education. The reference school year is 2021-22. See the 2022 Eurydice report on structural indicators for monitoring progress towards EU-level targets.

-

210.Cyprus and Malta are the exceptions, where compulsory teaching of digital competences is not introduced until lower secondary school (seventh grade). Albeit not compulsory, digital competence is addressed as a cross-curricular subject at primary level in both countries (and integrated in other compulsory subjects in Cyprus). In Belgium, Germany, Ireland, the Netherlands and Slovenia, top-level education authorities have not established a compulsory starting grade for the teaching of digital competences for all students.

-

211.Denmark, Estonia, Greece, Spain, France, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Poland, Portugal, Finland and Sweden.

-

212.Curriculum approaches to digital competence may include teaching through a cross-curricular topic, a separate subject, or several other subjects (integrated approach). Digital competences are taught as a compulsory separate subject from first grade in four Member States (Greece, Latvia, Poland and Portugal).

-

213.Education systems have different ways of addressing digital competence in terms of curriculum content and learning outcomes, but Member States tend to include explicit learning outcomes in all five areas of digital competence as defined by the European Digital Competence Framework. This is consistent with an earlier finding from the 2019 Eurydice report on digital education at school.

-

214.Invariably, these tests take place in lower secondary education.

-

215.In the Flemish Community of Belgium (lower secondary education), Czechia, Estonia, France (primary education), Luxembourg and Finland, digital competences are assessed through sample tests that aim to monitor the quality of the education system rather than measure the attainment levels of individual students.

-

216.The French Community of Belgium, Bulgaria, Denmark (primary education), Germany, Ireland, Spain, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Hungary, Malta (primary education), the Netherlands, Poland (general lower secondary education), Portugal, Romania, Slovenia, Slovakia and Sweden.

-

217.The German-speaking community of Belgium, the Flemish Community of Belgium (primary education), Greece, Croatia, Cyprus, Austria (primary education) and Poland (primary education).

-

219.The French Community of Belgium, Bulgaria, Czechia, Denmark, Estonia, Ireland, Spain, France, Italy, Cyprus, Lithuania, Hungary, Poland, Romania and Sweden.

-

220.Appointment of a digital coordinator is only a top-level requirement in 10 education systems in the EU (the Flemish Community of Belgium, Spain, France, Italy, Cyprus, Luxembourg, Malta, Austria and Slovenia).

-

221.Establishing a school digital plan is only a top-level requirement in four countries (Ireland, France, Italy, and Portugal), but forms part of the school development plan in another five countries (Spain, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg and Austria).

-

222.Bulgaria, Luxembourg, Austria and Finland do not use external school evaluation.

-

223.The Flemish Community of Belgium, Czechia, Germany, Estonia, Ireland (general lower secondary education), Spain, France, Lithuania, Hungary, Malta, Poland, Romania and Sweden.

-

224.The main data source utilised in this chapter is the Digital Skills Indicator 2.0. For further details, see the opening footnote of this chapter.

-

225.If only considering individuals in the labour force (employed and unemployed), the share increases to 62%. Monitor Toolbox

-

226.This is one of two Digital Decade targets concerning digital skills. The second target stipulates that there should be 20 million employed ICT specialist in the EU by 2030, with convergence between women and men. The Digital Decade targets are outlined in a 2021 Commission Communication. The 80% target is also mentioned in the European Pillar of Social Rights Action Plan. For an analysis of gender disparities in ICT, see Chapter 5.

-

227.The 2021 data are not comparable to data from previous years due to a change in the survey methodology. From 2021 on, individuals need to have skills in an additional fifth domain, ‘safety’, in order to be classified as having basic digital skills. For a more comprehensive assessment of EU progress on digital skills, see the Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) 2022.

-

228.This is on par with individuals classified as ‘students’, where 77% reported at least basic digital skills in 2021. Monitor Toolbox

-

229.This contrasts with the adult population, where there is a small gender gap in favour of men. Interestingly, there is no gap in the 25-54 age bracket, with gaps only present in the 16-24 age bracket (in favour of women) and the 55-74 age bracket (in favour of men). A different picture emerges when taking into account more advanced digital skills (above basic). More women than men report to have above basic digital skills in the 16-25 age bracket, while the opposite is the case for the 25-55 and 55-75 brackets. Monitor Toolbox

-

230The EU-level share of adults reporting at least basic digital skills is 15 percentage points higher in cities (61%) compared to rural areas (46%). Monitor Toolbox

-

231.At EU level, the share of native-born people reporting at least basic digital skills (55%) is higher compared to the foreign-born population (49%). Among the latter, there is a marked difference between EU mobility (53%) and migration (46%). Monitor Toolbox

-

232.Young people (aged 16-24) are at less of a disadvantage, regardless of attainment level. The gap between young people with a low level of education (64%) and those with a medium level of education (73%) was 9 percentage points in 2021. Although young people with a low level of education are better off than those with a medium level of education in the population at large, they are still at a considerable disadvantage compared to their peers with higher levels of educational attainment. This is highlighted by the substantial distance between them and highly educated young people (89%). Monitor Toolbox

-

233.The education and training sector has a widely recognised role in responding to the overarching goals of the green transition set out in the 2019 Communication on the European Green Deal and the Biodiversity Strategy for 2030.

-

234.Prominent examples are the 2022 Council Recommendation on learning for the green transition and sustainable development, the 2022 Council Recommendation on ensuring a fair transition towards climate neutrality, the European Skills Agenda (notably Action 6), the Education for Climate Coalition and a European sustainability competence framework (Box 25).

-

235.In addition, a 2021 pan-European survey by the European Environmental Bureau suggests that climate change is a top priority for many young Europeans (46%), who consider climate change and environmental degradation as the most important issues facing the world, even in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. See also the final outcome of the Conference on the Future of Europe, including 49 proposals. In particular, proposal 6 aims to increase knowledge, awareness, education and dialogues on environment, climate change, energy use, and sustainability. Proposal 46 on education includes learning about environmental sustainability and its connection to health, biodiversity and all ecological issues.

-

236.See the 2022 Council Recommendation on learning for the green transition and sustainable development.

-

237.See a 2022 analytical report from the European Expert Network on Economics of Education (EENEE).

-

238.See a 2022 Eurydice report on mathematics and science learning in schools. Five topics are used to operationalise how environmental sustainability is included in curricula: recycling; renewable and non-renewable sources of energy; air, soil and water pollution; biodiversity; and greenhouse effect. The Netherlands is the only Member State that did not mention any of the selected topics in its curriculum, but care for the environment is a compulsory part of its primary and lower secondary education and, furthermore, schools have a high level of autonomy.

-

239.The report compares the environmental behaviour, awareness and attitudes of 15-year-old students against their socio-economic background, scientific knowledge, global competences, collaborative problem-solving skills and financial skills. It adapts GreenComp (Box 25) to various rounds of PISA data. The PISA Science Expert Group is currently developing the PISA 2025 Science Framework, which includes a focus on climate competence.

-

240.The assessment of gender disparities is based on PISA 2015.

Publication details

- Catalogue numberNC-AJ-22-002-EN-Q

- ISBN978-92-76-54154-7

- DOI10.2766/239886