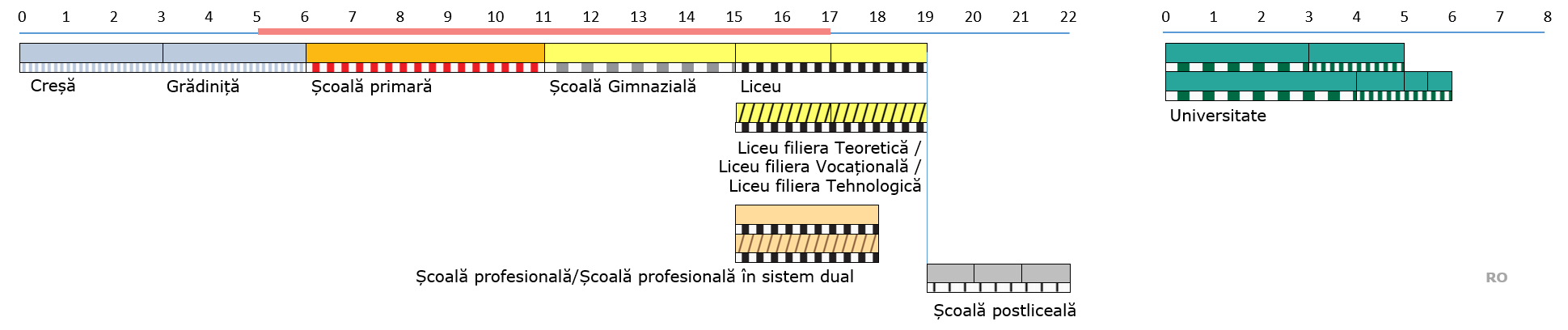

1. Key indicators

Figure 1 – Key indicators overview

| Romania | EU-27 | ||||||||

| 2010 | 2020 | 2010 | 2020 | ||||||

| EU-level targets | 2030 target | ||||||||

| Participation in early childhood education (from age 3 to starting age of compulsory primary education) |

≥ 96% | 84.1%13 | 78.6%19 | 91.8%13 | 92.8%19 | ||||

| Low achieving eighth-graders in digital skills | < 15% | : | : | : | : | ||||

| Low achieving 15-year-olds in: | Reading | < 15% | 40.4%09, b | 40.8%18 | 19.7%09, b | 22.5%18 | |||

| Maths | < 15% | 47.0%09 | 46.6%18 | 22.7%09 | 22.9%18 | ||||

| Science | < 15% | 41.4%09 | 43.9%18 | 17.8%09 | 22.3%18 | ||||

| Early leavers from education and training (age 18-24) | < 9% | 19.3%u | 15.6% | 13,8% | 9,9% | ||||

| Exposure of VET graduates to work based learning | ≥ 60% | : | : | : | : | ||||

| Tertiary educational attainment (age 25-34) | ≥ 45% (2025) | 20.7% b | 24.9% | 32.2% | 40.5% | ||||

| Participation of adults in learning (age 25-64) | ≥ 47% (2025) | : | : | : | : | ||||

| Other contextual indicators | |||||||||

| Education investment | Public expedienture on education as a percentage of GDP | 3.3% | 3.6% | 5.0% | 4.7%19 | ||||

| Expenditure on public and private institutions per FTE/student in € PPS | ISCED 1-2 | €1 66812 | €2 48818 | €6 07212,d | €6 35917,d | ||||

| ISCED 3-4 | €1 76912 | €3 22218 | €7 36613,d | €7 76217,d | |||||

| ISCED 5-8 | €4 03512 | €5 46018 | €9 67912,d | €9 99517,d | |||||

| Early leavers from education and training (age 18-24) | Native | 19.3% | 15.6% | 12.4% | 8.7% | ||||

| EU-born | : | :u | 26.9% | 19.8% | |||||

| Non EU-born | :b,u | : | 32.4% | 23.2% | |||||

| Upper secondary level attainment (age 20-24, ISCED 3-8) | 78.4%b | 83.0% | 79.1% | 84.3% | |||||

| Tertiary educational attainment (age 25-34) | Native | 20.7%b | 24.8% | 33.4% | 41.3% | ||||

| EU-born | :b,c | :c | 29.3% | 40.4% | |||||

| Non EU-born | :b,u | :u | 23.1% | 34.4% | |||||

Source: Eurostat (UOE, LFS, COFOG); OECD (PISA). Further information can be found in Annex I and in Volume 1 (ec.europa.eu/education/monitor). Notes: The 2018 EU average on PISA reading performance does not include ES; the indicator used (ECE) refers to early-childhood education and care programmes which are considered by the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) to be ‘educational’ and therefore constitute the first level of education in education and training systems – ISCED level 0; FTE = full-time equivalent; b = break in time series, c = confidential, d = definition differs, u = low reliability, := not available, 09 = 2009, 12 = 2012, 13 = 2013, 17 = 2017, 18 = 2018, 19 = 2019.

Figure 2 - Position in relation to strongest and weakest performers

Source: DG Education, Youth, Sport and Culture, based on data from Eurostat (LFS 2020, UOE 2019) and OECD (PISA 2018).

2. Highlights

- The pandemic has negatively impacted students’ well-being in education and risks worsening educational outcomes and inequalities. Students from disadvantaged backgrounds, including Roma and those from rural areas, were particularly affected.

- Romania put forward a vision to reform its education and training system, setting out ambitious targets for raising educational outcomes. Swift action and sustained efforts will be needed to achieve progress and improve quality, equity and labour market relevance.

- The Recovery and Resilience Facility will facilitate large-scale investments related to education and training.

- Low participation in adult learning poses obstacles to the development of the skills needed in the economy.

3. A focus on well-being in education and training

In recent years, students’ well-being has received increased attention at policy level. Well-being has been integrated in the new quality assurance framework, which entered into force in September 2021. The framework defines well-being as the predominantly positive attitudes of children and young people towards learning, school, teachers and colleagues. They are determined and influenced by individual, family, school and community factors. Measures taken by schools to support students’ well-being will be assessed as part of the external evaluations carried out by the quality assurance body in pre-university education (ARACIP)1. Schools will also have to reflect on these aspects in their self-evaluations. Recent measures to improve well-being at school include the 2020 methodological guidance for tackling violence and bullying. The concept of well-being was also embedded in the various curriculum syllabi in primary and lower secondary education, for example, as part of personal development, key social competences and digital competences (Palade et al, 2020). Nevertheless, in practice, there has been limited adoption of the concept in concrete learning practice and experiences. In higher education, there is no official definition of well-being. However, evaluation criteria related to education efficacy refer to the requirement for universities to create a favourable learning environment for students and to address students’ expectations, needs and satisfaction level in relation to their learning programme (ARACIS 2019).

Romanian students report a lower level of well-being than their European peers. As part of the 2018 Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), almost 34% of Romanian 15-year-olds said they were bullied at least a few times a month. This is one of the highest proportions in the EU, significantly above the EU average of 22.1%. Disadvantaged students reported a much higher incidence of bullying than their more advantaged peers (39%, compared to 26.7%). The performance of students who were bullied was 40 points lower, equivalent to about a year of schooling. Compared to the EU average, twice as many Romanian teenagers had skipped a day of school at least once in the two-week period before they took the PISA test (50%, compared to 25%). Furthermore, almost 45% of Romanian students felt that they do not belong at school, more than on average in the EU (35%).

The pandemic has had a negative impact on Romanian students, with those from disadvantaged backgrounds particularly affected. The pandemic worsened the well-being of children by limiting their access to basic public services, restricting socialisation, and by reducing family incomes, especially in disadvantaged families (World Vision, 2020). The COVID-19 outbreak led to extended periods of school closures2 and a shift to distance learning. Although measures were taken to facilitate education continuity, a proportion of students did not engage in remote learning either completely or effectively. For example, in a survey conducted after the first COVID 19 wave (National Centre for Policy and Evaluation in Education, 2020), 65% of respondent school teachers said that all their students engaged in distance learning (69% in urban areas and 58% in rural areas) and 21% stated that more than half of their students did so (18% in urban, 25% in rural). Nevertheless, parents’ responses showed that this happened with a varying degree of frequency, while teachers’ responses indicated a varying coverage of subjects and of the curriculum (ibid). To facilitate distance learning, Romania launched the ‘School from home’ national programme to supply digital devices to students from disadvantaged backgrounds. However, lack of devices continued to be an obstacle in the 2020/2021 school year, particularly affecting students from disadvantaged backgrounds, including those from rural areas and from Roma communities. An additional EUR 50 million will be allocated through the REACT-EU initiative to support e learning, to purchase devices and other equipment, especially in rural areas.

Box 1: Remedial education financed under REACT-EU

REACT-EU will support remedial education measures to compensate for learning losses caused by school closures. The EUR 30 million allocated to this project will fund after-school activities and remedial lessons for 168 000 disadvantaged students, including from rural areas and Roma communities. Considering the disproportionate effects on the learning outcomes of disadvantaged children, such measures are important to avoid widening the educational gap in Romania.

4. Investing in education and training

General government expenditure on education increased markedly in 2019, but remained among the lowest in the EU. In 2019, spending on education increased in real terms by almost 21%, marking the strongest percentage growth in the EU that year, significantly above the average growth of 1.9%. The increase was driven to a large extent by the 2019 pay raise for teachers. Spending also increased across all other categories like goods and services in education, educational infrastructure development and maintenance, as well other non-staff related costs. Although Romania’s general government expenditure jumped to 3.6% of GDP in 2019, it remains significantly below the EU average of 4.7% of GDP. Nevertheless, Romania’s education spending was slightly above the EU average as a proportion of total government spending (10.1%, compared to EU-27:10%), which points to a rather low level of public spending.

Box 2: The National Recovery and Resilience Plan

Romania’s Recovery and Resilience Plan contains grants and loans totalling EUR 29.2 billion out of which more than 10% will support education and skills-related measures. At the time of closing this report (i.e. 19 October), the plan had been endorsed by the European Commission and was awaiting approval by Council.

The RRF will support the implementation of various reforms announced by the Educated Romania Report (Presidential Administration 2021), which sets out the vision for the development of education and training by 2030 and envisages an in-depth restructuring of the education and training system. The legislative package ensuring implementation of the Educated Romania project will be adopted in the third quarter of 2023 and will cover several priority areas. These include digitalisation, resilience (i.e. mechanisms for rapid adaptation to crisis situations, increasing quality services in disadvantaged areas, students’ resilience, etc.), teaching careers, management and governance in education, as well as financing in education, educational infrastructure, curricula and evaluation, inclusive education, functional literary and promoting education in STE(A)M (science, technology, arts, engineering and mathematics).

The reforms and investments included in the National Recovery and Resilience Plan cover all levels of education, with measures aiming to improve early-childhood education, reduce early-school leaving, increase the quality of vocational education and training and improve educational infrastructure. The plan will support digital skills development for students and teachers as well as the reform of management and government in education.

5. Modernising early childhood and school education

Participation in early childhood education and care is decreasing. Romania is among the EU countries where participation rates in early childhood education declined compared to 2014 (see Figure 3). The latest data available show an enrolment rate of only 78.6% for children between the age of 3 and the starting age of compulsory education. This figure was one of the lowest in the EU in 2019, significantly below the European average of 92.8%. Participation rates are particularly low in rural areas3 and for the Roma. These low participation rates are of concern given the importance of early years education in laying the foundations for future educational outcomes and social inclusion. Furthermore, in 2019 the participation rate in the age group 0-3 was 14%, significantly below the EU average of 35.5%. As part of the Educated Romania report, Romania set an ambitious target for 2030 of raising participation rates for children aged 0-3 to 30% and to 96% for children between the ages of 3 to the starting age of school education. The latter target also corresponds to the EU-level target for 2030.

Figure 3 – Participation in early childhood education of pupils from age 3 to the starting of compulsory primary education, 2014 and 2019 (%)

Source: UOE, educ_uoe_enra21

The Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) will support improvements in quality and access to early childhood education and care. As part of its Recovery and Resilience Plan (RRP), Romania committed to delivering a revised framework for early childhood education. Preparatory work was supported by the European Social Fund. Furthermore, a large-scale training programme for early education professionals will be developed and implemented with RRF funding. At the same time, access will be improved through the building of 110 crèches, significantly increasing the supply of childcare institutions (currently there are less than 400 such institutions, located almost exclusively in urban areas). The RRF will also fund the development of 412 complementary early childhood education and care services in disadvantaged communities.

A national programme will be rolled out to reduce the high rate of early school leaving. In 2020, the proportion of early leavers from education and training among 18-24 year-olds was 15.6%. Although the rate has decreased in recent years, it remains significantly higher than the EU average of 9.9% and represents a structural challenge for the school system. Early school leaving is higher in rural areas (23%) and among disadvantaged groups, including Roma. These are also the groups that were disproportionately affected by the impact of COVID-19 in education and the school closures. To avoid a worsening of the situation and to reduce early school leaving, a grant programme for schools will be implemented between 2022 and 2026 with funding from the Recovery and Resilience Facility. With a budget of EUR 400 million, the scheme will enable the development of various educational support measures and social programmes to prevent and reduce drop-out. More than 2 500 schools will be eligible for funding. In addition, an early warning tool developed and currently being piloted with EU support will be rolled out across the country.

Figure 4 – Early leavers from education and training, 2010 and 2020 (%)

Source: LFS, edat_lfse_14.

International and national student assessments show the need to improve learning outcomes and reduce inequalities in education. The 2018 OECD Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) showed that more than 40% of Romanian 15-year-olds lacked basic skills in reading, mathematics or science. These rates of low achievement were about twice as high as the European average (22.5% for reading, 22.9% for mathematics and 22.3% for science). Students from disadvantaged backgrounds had substantially higher rates of low achievement (e.g. 62% in reading compared to 19% among advantaged peers4). Apart from the strong impact of socioeconomic status on educational performance, a large rural-urban gap in education also persists. In 2021, 23% of eighth graders who sat the national evaluation did not obtain the minimum pass mark of 5. This was the case for 37% of students from schools in rural areas and 11% in urban areas. This gap is of concern given that more than 40% of students in primary and lower secondary attend schools in rural areas. Furthermore, 30% of candidates failed the baccalaureate exam taken at the end of the 12th grade, of which 34.5% at high schools located in rural areas, compared to 20% in urban areas. On educational outcomes, the Educated Romania report outlined ambitious targets to be achieved by 2030. One such target is to halve the rate of underachievers in reading from 40 to 20%, as measured by the PISA test. Romania also aims to halve the proportion of students underperforming simultaneously in reading, mathematics and sciences, from 30% to 15%. Achieving such progress is likely to require substantial efforts to address the root causes of low educational outcomes and high inequalities in education, including targeted policies to compensate for learning losses due to the pandemic and systematically focusing on the needs of disadvantaged students and on the situation of students in rural areas.

Reforming teacher policies remains key for achieving progress in school education. Research in the field of education has identified teachers and teaching methods as the most important factor affecting the quality of education. Thus, successfully implementing Romania’s aspirations to raise learning outcomes and develop a competence-based student-centred approach to teaching and learning depend largely on its teachers (OECD, 2020). Nevertheless, previous reports have identified a number of critical aspects facing the teaching profession. These start with insufficient practical preparation in initial teacher education and lack of rigorous selection (OECD, 2017). Although 70% of secondary school teachers5 report taking part in continuous professional development (CPD), in general teachers perceive training as insufficiently adapted to their needs (ISE, 2018). Career progression is not accompanied by an increase in the complexity of responsibilities, while additional tasks such as mentoring or training others are not remunerated (OECD, 2017, Presidential Administration, 2021). Schools in rural areas struggle to attract highly qualified staff, and the number of available support specialists remains insufficient. The merit-based allowance tends to encourage a narrow focus on preparing pupils for tests and academic competitions, rather than encouraging progress among low performing students or those from disadvantaged backgrounds. In response to these challenges, the Educated Romania report outlined a number of measures to improve the quality of initial teach education and continuous professional development, as well as measures to develop a flexible career management system

Several investments financed under the Recovery and Resilience Facility aim to modernise digital infrastructure in schools and facilitate digital education. European surveys6 and the national mapping of educational infrastructure needs (Ministry of Education and Research, 2018) have shown that digital infrastructure in schools lags significantly behind, especially in rural areas. Furthermore, only 57% of young Romanians aged 16-19 have basic or above-basic digital skills (EU average: 82%), and several areas of teachers’ digital skills are in need of strengthening (European Commission 2019). To support the acquisition of digital skills, the Recovery and Resilience Facility will finance the modernisation of computer laboratories and investments in various other IT equipment (e.g. smart screen, laptops, etc.) Digital educational content, including textbooks and open educational resources, will also be developed, and a platform to assess students’ skills will be set up with RRF support. The investment package further includes measures to support the uptake of digital pedagogies and improve teachers’ digital skills. For example, the requirements for digital skills training in initial teacher education will be updated, and a large-scale training programme aligned with the European Digital Competence Framework will be implemented. Some 45 000 school teachers (almost 50% of Romania’s teachers), will receive training on how to incorporate digital tools in teaching and learning.

6. Modernising vocational education and training and adult learning

The pandemic has posed challenges for the practical side of learning in vocational education and training. The shift to remote learning and the temporary closure of some businesses particularly affected the dual element of some VET programmes, making the delivery of work-based learning impossible in many cases. The national ‘School from home’ programme was also applied to VET programmes. Furthermore, the existing ESF-funded CRED (Relevant Curriculum, Open Education) project was used to facilitate access to online resources and e-learning platforms for all students and teachers, including those in VET. In September 2020, the National Centre for Technical VET Development (CNDIPT) published methodological benchmarks for strengthening teaching and learning in initial VET, as well as a support guide for VET teachers.

Improving the quality and labour market relevance of VET remains a challenge to be tackled. In 2020 a new ESF-funded project (ReCONECT) was launched, aimed at better matching labour market demand and supply for skills. This project will build on existing skills forecasting data to develop monitoring mechanisms for new graduates and their career prospects. It aims to support labour market integration of recent graduates. Only 68.5% of 20-34 year-olds who have recently completed vocational education and training were employed in 2020, compared to the European average of 76.1%.

An overhaul of the dual education system has been announced. Romania plans to change the way in which dual education is organised. The objective is for VET to become predominantly dual education and to ensure better alignment with the needs of the labour market, ultimately increasing the attractiveness of this form of education. The plans also envisage a revision of the current baccalaureate exam and creation of a distinct educational route that will allow graduates from VET programmes to join technical higher education. To support the planned reform of the VET sector, the RRF will invest in equipping VET high schools, including agricultural schools, with laboratories and IT laboratories. In addition, support schemes will finance the development of 10 regional consortia between territorial VET actors (local authorities, schools, universities, chambers of commerce and businesses) in order to deliver effective training in dual VET.

Low participation in adult learning poses obstacles to the development of skills needed in the economy. In 2020, Romania continued to have the lowest participation in adult learning in the EU (1.0%, significantly below the 9.2% EU average). Romania is also near the bottom of the EU table in the proportion of individuals with basic or above-basic overall digital skills (31% in 2019, compared to the EU average of 56%). In terms of the policy framework, work started at the end of 2020 on developing the national strategy for the continuous training of adults (2021-2027), but the project is estimated to take 36 months until completion. Coupled with the low level of educational attainment, the adult learning data above point towards the need to improve the skills supply to the labour market in general. In addition, the employment rate of adults with low educational attainment (56% for those completing less than lower secondary education), coupled with difficulties in accessing continuous education and training, pose significant challenges to individuals’ ability to integrate into the job market. This in turn has a limited effect on sustainable growth.

7. Modernising higher education

Tertiary educational attainment is low. Only 25% of the population aged between 25 and 34 holds a tertiary education degree. Although the proportion has improved over time, it is significantly below the EU average of 40.5% and the EU-level target of 45% by 2030. As outlined in the Educated Romania report, Romania aims to increase tertiary attainment in the age group 30-34 to 40% by 2030. In 2020, the value of this indicator was 26.4%, significantly below the EU average of 41%. Achieving such an increase is likely to require sustained efforts to overcome the main drivers of low participation in higher education and an insufficient number of graduates. For example, participation rates are affected by persistently high rates of early school leaving, the low passing rate at the baccalaureate exam (less than half of the age-specific cohort is successful in this exam (UEFICSCI, 2020a), as well as by the low participation of students from disadvantaged backgrounds. Participation rates have somewhat increased in recent years. In the 2019/2020 academic year 37.4% of Romanians aged between 19 and 23 were pursuing a Bachelor’s programme.

Recent studies and data shed light on the impact and value added of measures to improve equity and reduce drop-out rates. A recent survey (UEFISCDI, 2020b) shows that in the 2018/2019 academic year, 10% of students at the public universities surveyed were receiving social scholarships. These scholarships are seen as having a positive impact on reducing the rate of drop-out and improving graduation rates in nominal time. However, scholarships seem not to motivate more students from disadvantaged backgrounds to access higher education. Nevertheless, a slightly increasing interest was noted for the dedicated places for graduates from upper secondary schools located in rural areas (UEFICSDI, 2020c). Analysis revealed that these study places are insufficiently known to eligible beneficiaries, and that universities have not yet taken sufficient measures to promote them (ibid). Dedicated places for Roma also continue to be financed, with data showing that out of the 386 places allocated to public universities in 2020, 371 were occupied. At the same time, universities and colleges are receiving grants to reduce drop-out rates in the first year of study. Activities provided include remedial measures, tutoring, career counselling and guidance, as well as setting up learning centres to support students at risk of dropping out. As a result of these measures, the retention rate in the first year of study in universities included in the grant scheme has increased. Additional support for higher education will be provided by the Recovery and Resilience Facility for digitalisation and modernisation of auxiliary infrastructure such as dormitories and canteens. 40% of these new or modernised places in dormitories will be allocated to students from disadvantaged backgrounds.

There are relatively low numbers of tertiary educated professionals, and their skills are insufficiently aligned with labour market needs. The latest available data show that for every 1 000 people aged 20-29 there were 46.2 higher education graduates (ISCED 5-8) in Romania, compared to 61.9 on average across the EU. The percentage of graduates in science, technology, engineering and mathematics is one of the highest in the EU (30%), but due to the low number of graduates, the availability of specialists is low. Emigration further reduces the number of tertiary educated professionals, with an estimated 40% of Romania’s graduates in the 24-64 age group having emigrated (World Bank, 2019). Before the start of the pandemic, skills shortages had been documented in key sectors, including ICT, health and education, as well as for science and engineering professionals and technicians (World Bank, 2020). At the same time, graduates’ skills are seen as insufficiently aligned with the needs of the labour market. Studies show that many employers view the curricula as using outdated teaching methods and as insufficiently focused on the practical application of knowledge, problem solving and team cooperation (World Bank, 2020). To improve the labour market relevance of higher education and facilitate digitalisation, a grant scheme will be set up with funding from the RRF, benefiting 60 universities (66% of the total) with investments in digital equipment, training of staff and other measures to improve students’ digital skills.

8. References

ARACIP, (2021), Agenția Română de Asigurare a Calității în Învățământul Preuniversitar, Ghiduri pentru aplicarea unitară a standardelor de evaluare, Volumul 2: Evaluarea internă și externă a stării de bine

ARACIS, (2019). Agenția Română de Asigurare a Calității în Învățământul Superior, Ghiduri pentru aplicarea unitară a standardelor de evaluare. Ghid intocmire raport de evaluare interna, https://www.aracis.ro/ghid-raport-autoevaluare-evaluare-licenta/

Cedefop ReferNet Romania (2020). Romania: responses to the Covid-19 outbreak. https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/news-and-press/news/romania-responses-covid-19-outbreak

Cedefop ReferNet Romania, 2021

European Commission (2019), 2nd Survey of Schools: ICT in education. DG CNECT. https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/news/2nd-survey-schools-ict-education (see also national reports)

UEFISCDI (2020a), Anticiparea principalelor tendințe demografice și a impactului lor asupra populației de studenți din România

UEFICSDI (2020b), Politici publice privind echitatea în învăţământul superior: Impactul burselor sociale https://uefiscdi.gov.ro/resource-825200-20210208_studiu-de-impact-burse-sociale_conf-publicatie-snspa2.pdf

UEFISCDI (2020c), Politici publice privind echitatea în învăţământul superior: Impactul politicii de alocare a locurilor speciale pentru absolvenţi ai liceelor din mediul rural https://uefiscdi.gov.ro/resource-825682-20210208_studiu-de-impact-rural_conf-publicatie-snspa2.pdf

MEN (2018), Ministerul Educației Naționale, Strategia pentru modernizarea infrastructurii școlare.

National Centre for Policy and Evaluation in Education (2020), Distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemics

OCDE (2020), Improving the teaching profession in Romania (Document de sinteză privind profesia de cadru didactic), https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/improving-the-teaching-profession-in-romania_3b23e2c9-en

OECD (2019), TALIS 2018 Results (Volume I): Teachers and School Leaders as Lifelong Learners, TALIS.

OECD (2017), Reviews of Evaluation and Assessment in Education, Kitchen, H., et al., Romania 2017. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264274051-en

Palade, E. et al (2020). Repere pentru proiectarea, actualizarea și revizuirea curriculumului național [Reference Framwork for designing, updating and revising the national curriculum]. Ministry of National Education, CRED Project. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1r8YZCPUG_Tipm1muMpW29XMJ0nBEefj9/view

IŞE (2018), Institutul pentru Ştiinţe ale Educaţiei, Analiza de nevoi a cadrelor didactice din învățământul primar și gimnazial.

Raport al investigației realizate în cadrul proiectului CRED (Analysis of the training needs of primary and lower secondary teachers. Report on the results of the research conducted under the CRED project). Available at: http://www.ise.ro/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Raport-final-analiza-nevoi.pdf

World Vision 2020, Mihalache, F., Neguţ, A., Tufă, L. (2020). Bunăstarea copilului din mediul rural https://worldvision.ro/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Raport-de-Bunastare-a-Copilului-din-Mediul-Rural-2020.pdf

Presidential Administration, 2021, Rezultatele proiectului România Educată http://www.romaniaeducata.eu/rezultatele-proiectului/

World Bank (2019), Migration and Brain Drain, Europe and Central Asia Economic Update, Fall 2019: Migration and Brain Drain. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/32481

World Bank (2020), Markets and People: Romania Country Economic Memorandum. International Development in Focus. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/33236

Annex I: Key indicators sources

| Indicator | Eurostat online data code |

| Participation in early childhood education | educ_uoe_enra21 |

| Low achieving eighth-graders in digital skills | IEA, ICILS. |

| Low achieving 15-year-olds in reading, maths and science | OECD (PISA) |

| Early leavers from education and training | Main data: edat_lfse_14. Data by country of birth: edat_lfse_02. |

| Exposure of VET graduates to work based learning | Data for the EU-level target is not available. Data collection starts in 2021. Source: EU LFS. |

| Tertiary educational attainment | Main data: edat_lfse_03. Data by country of birth: edat_lfse_9912. |

| Participation of adults in learning | Data for the EU-level target is not available. Data collection starts in 2022. Source: EU LFS. |

| Public expenditure on education as a percentage of GDP | gov_10a_exp |

| Expenditure on public and private institutions per student | educ_uoe_fini04 |

| Upper secondary level attainment | edat_lfse_03 |

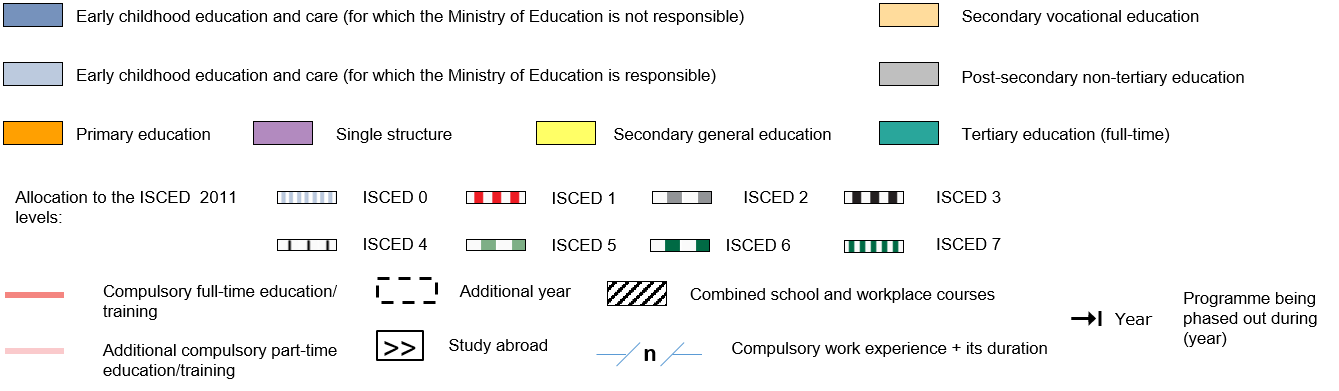

Annex II: Structure of the education system

Source: European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2021. The Structure of the European Education Systems 2021/2022: Schematic Diagrams. Eurydice Facts and Figures. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Any comments and questions on this report can be sent to: