Annual Report on the Situation of Asylum in the EU in 2017

The 2017 EASO Annual Report on the Situation of the Asylum in the EU aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the situation of asylum in the EU+ (EU Member States plus Norway, Switzerland, Iceland and Liechtenstein) by examining requests for international protection to the EU, analysing application and decision data, asylum trends, including key challenges and responses during the year, major institutional and legal developments and providing an overview of the practical functioning of the Common European Asylum System (CEAS). Input is derived from a variety of sources, including EU+ countries' asylum administrations, UNHCR, civil society, academia and other expert stakeholders.

The report looks at developments related to international protection throughout the year, both at European and at national level, such as the reform of the CEAS, implementation of the European Agenda on Migration, legislative and policy developments in national asylum systems and EASO’s support via training and operational plans. Significant asylum-related legal judgments handed down across Europe are also outlined. Additionally, key information on asylum trends is provided via Eurostat data, complemented with selected EASO’s Early Warning and Preparedness System (EPS) statistics. This provides accurate, timely and complete insights into the practical functioning of asylum in Europe.

Annual report 2017 is also available in the PDF format

| Annual Report |  |

| Read the Executive Summary in your language | [BG] [CS] [DA] [DE] [EL] [EN] [ES] [ET] [FI] [FR] [GA] [HR] [HU] [IT] [LT] [LV] [MT] [NL] [PL] [PT] [RO] [SK] [SL] [SV] |

Introduction

The EASO Annual Report on the Situation of Asylum in the European Union is drawn up in accordance with Article 12.1 of the EASO Regulation (1 Regulation (EU) No 439/2010 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 May 2010 establishing a European Asylum Support Office http://easo.europa.eu/wp-content/uploads/EASO-Regulation-EN.pdf. ).

Its objective is to provide a comprehensive overview of the situation of asylum in the EU (including information on Norway, Switzerland, Liechtenstein and Iceland), describing and analysing flows of applicants for international protection, major developments in legislation, jurisprudence, and policies at the EU+ and national level and reporting on the practical functioning of the Common European Asylum System (CEAS). As part of the Report, EASO also indicates its activities undertaken in 2017 in respective thematic areas.

The production process follows the methodology and basic principles agreed by the EASO Management Board in 2013.

Primary factual information was obtained by EASO from EU+ countries in a process coordinated with the European Migration Network (EMN) (2 Unless otherwise stated, information on state practices refers to that input. ), to avoid duplication with the 2017 Annual Report on Migration and Asylum. Furthermore, the European Commission was consulted during the drafting process and actively contributed. In accordance with its role under Article 35 of the Geneva Convention of 28 July 1951 relating to the Status of Refugees, which is reflected in the EU Treaties and the asylum acquis instruments, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees made a special contribution to this report (indicated as UNHCR input).

Statistical information was primarily derived from Eurostat, an overview of which is available in the annex to the Report. Selected statistical data at EU+ level was also obtained from the EASO Early Warning and Preparedness System (EPS) data collection for additional insights, as well as for the section on Dublin procedures (due to unavailability of respective Eurostat data at the time of writing).

As in previous years, the report aims to provide an analysis based on a wide range of sources of information – duly referenced - to reflect the ongoing debate at European level and to help identify the areas where improvement is most needed (and thus where EASO and other key stakeholders should focus their efforts) in line with its declared purpose of improving the quality, consistency and effectiveness of the CEAS. To that end, EASO takes due account of information already available from other relevant sources, as stipulated in the EASO Regulation, including EU+ countries, EU institutions, civil society, international organisations, and academia. Contributions were also specifically sought from civil society with an open call for input from the EASO Executive Director to the members of the EASO Consultative Forum and other civil society stakeholders, inviting them to provide information on their work relevant for the functioning of the CEAS. EASO Network of Court and Tribunal members contributed to the report by providing relevant examples of national case law.

All efforts were made to provide a broad coverage of key relevant developments in areas covered by the Report within its scope. Yet the report makes no claim to be exhaustive; in particular state-specific examples mentioned in the report serve only as illustrations of relevant aspects of the CEAS.

The EASO Annual Report covers the period from 1 January to 31 December 2017 inclusive, but also refers to major recent relevant developments in the year of writing. Whenever possible, information referring to 2018 was based on the most up-to-date sources available at the time of adoption of the Report by EASO Management Board.

Executive Summary

The EASO Annual Report on the Situation of Asylum in the European Union 2017 provides a comprehensive overview of developments at European level and at the level of national asylum systems. Based on a wide range of sources, the Report looks into main statistical trends and analyses changes in EU+ countries as regards their legislation, policies, practices, as well as national case law. While the report focuses on key areas of the Common European Asylum System, it often makes necessary references to the broader migration and fundamental rights context.

Developments at EU level

Significant developments were reported in 2017 in the area of international protection in the European Union.

While the transposition of the recast asylum acquis package has been practically finalised, the new package to reform the Common European Asylum System remained under negotiations. The package was composed of proposals for strengthening the mandate of EASO by transforming it into the European Union Agency on Asylum; reform of the Dublin system; amendments to the Eurodac system; proposals for the new Asylum Procedures Regulation and Qualification Regulation; and revision of the Reception Conditions Directive.

In alignment with its responsibility to ensure correct application of EU law, the European Commission took steps in the framework of infringement procedures regarding Hungary, Czech Republic and Poland, and Croatia.

The Court of Justice of the European Union issued a number of judgments, seven of which concerned the implementation of the Dublin III Regulation, indicating the impact of the mass influx of asylum seekers during 2015 and 2016, as well as the impact of secondary movements. Specifically, the CJEU analysed issues pertaining to the legality of mass border crossings; the rights of asylum seekers in relation to Dublin III Regulation and the applicable time limits; the automatic transfer of responsibility, when the transfer has not been carried out; the transfer of seriously ill asylum seekers; detention in the context of the Dublin III Regulation; and applicability of Dublin III to persons granted subsidiary protection in the Member State of first entry. Other issues considered by the Court included the requirement to hold a hearing in the appeal proceedings; the right to be heard; exclusion from refugee status; and the use of homosexuality tests in asylum procedures. In the area of reception, the Court confirmed the grounds of detention of asylum applicants. The Court also dismissed the actions brought by Slovakia and Hungary against the relocation mechanism.

The implementation of the European Agenda on Migration continued in 2017, summarised in the Commission’s Communication on the Delivery of the European Agenda on Migration in September 2017. Reference was made to the hotspots approach, which was defined as the cornerstone of the response to migration challenges in the Mediterranean, with support provided in the framework of the approach by EASO to Italy and Greece.

In Italy, EASO deployed national experts, supported by interim staff and cultural mediators, providing information to arriving migrants, helping to accelerate the formal registration of requests for international protection across the country, supporting the National Asylum Commission and Territorial Commissions in their activities, and assisting the implementation of recent legislation on strengthening the protection of migrant children. In Greece, the hotspot approach is linked to the implementation of the EU-Turkey Statement, under which EU Heads of State or Government and Turkey agreed to tackle irregular migration, following the massive influx of migrants into the EU. The commitment of EU Member States to the EU-Turkey statement was reiterated in the Malta Declaration adopted by the members of the European Council on the external aspects of migration.

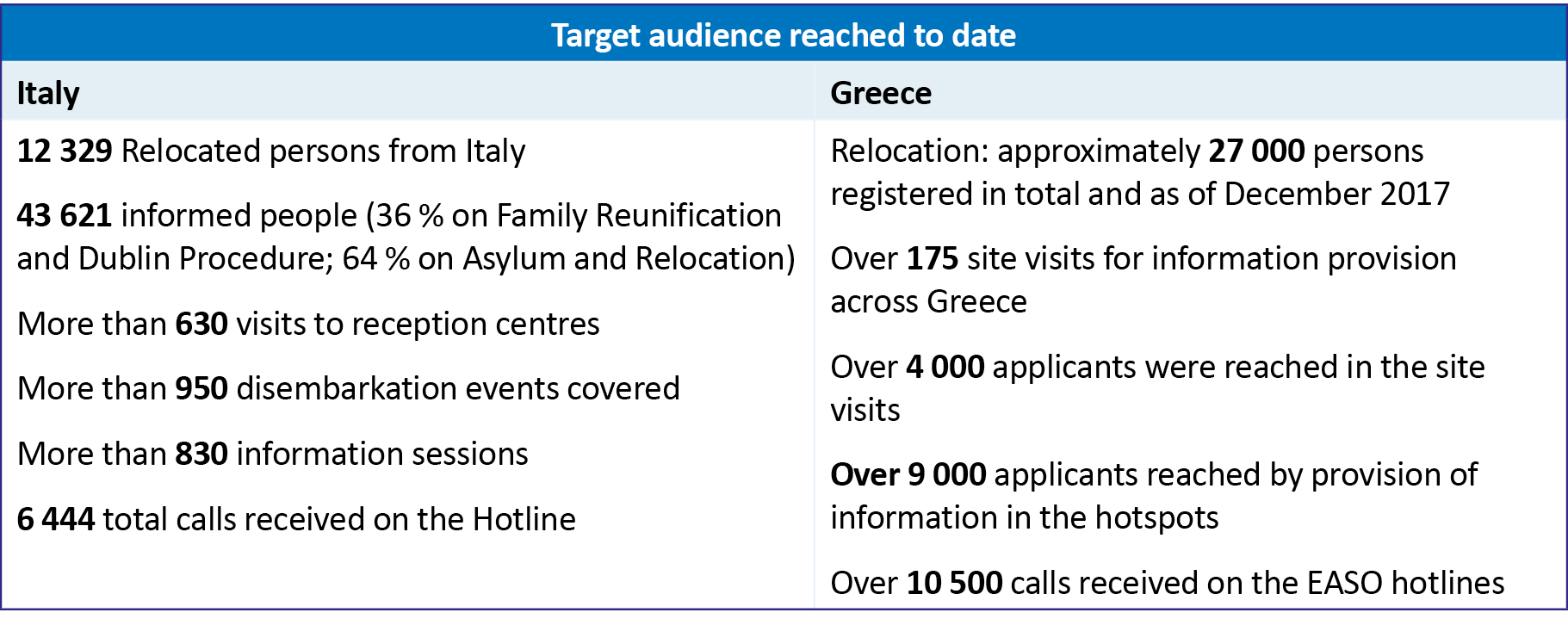

A key emergency mechanism launched under the Agenda concerned relocation activities, meant to provide a response to the high volumes of arrivals to the EU, which put particular pressure on frontline Member States. Relocation was established as a temporary and exceptional mechanism consisting in the transfer of up to 160 000 applicants in clear need of international protection from Greece and Italy over a period of two years until September 2017. The Council decisions on relocation expired on 26 September 2017. From Greece, all remaining eligible applicants were relocated by March 2018, while only 35 remained to be relocated from Italy as of 22 May 2018. By the end of 2017, there were 33 151 persons relocated, 11 445 from Italy and 21 706 from Greece. By end of March, the total number of relocated persons stood at 34 558 (12 559 from Italy and 21 999 from Greece). EASO provided broad operational support to the relocation process in Greece and Italy, since the launch of the process, and EASO activities have significantly expanded during the implementation period.

Throughout 2017, the European Union continued its cooperation with external partners. The Partnership Framework on Migration, introduced in June 2016, included initiatives carried out in and in cooperation with a number of priority countries of origin and transit, including Mali, Nigeria, Niger, Senegal and Ethiopia. Activities aimed at enhancing political dialogue; fighting trafficking and smuggling; strengthening protection and developing a new resettlement scheme for refugees from Turkey, the Middle East, and Africa by the end of 2019; improving management of returns; and launching job programmes under the EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa and the European External Investment Plan (EIP). These programmes support investments in partner countries in Africa and the European Neighbourhood.

International Protection in the EU+

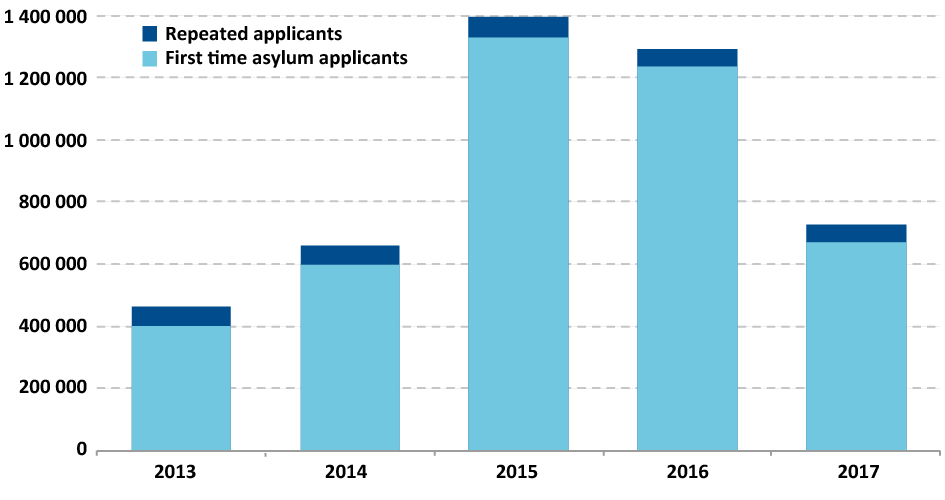

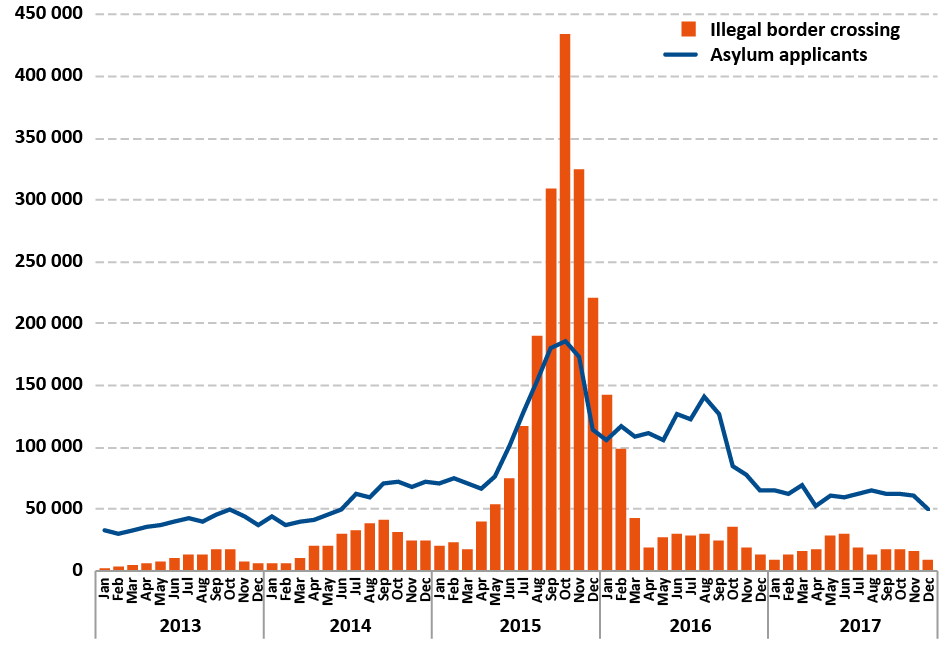

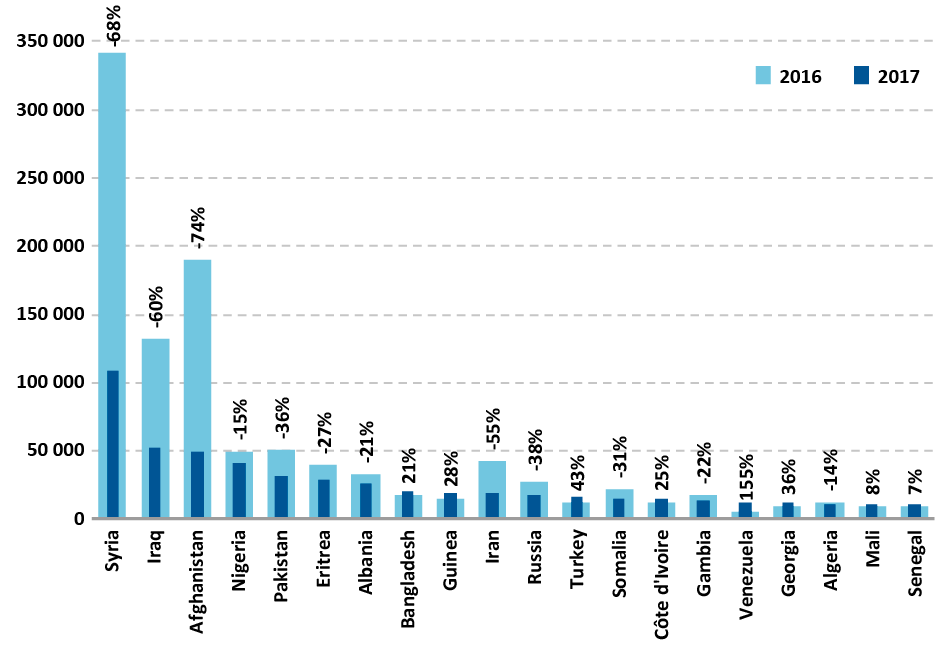

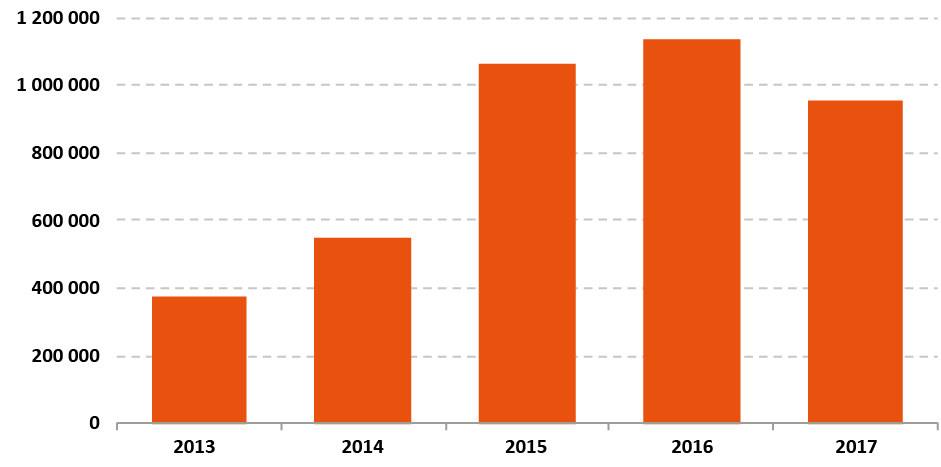

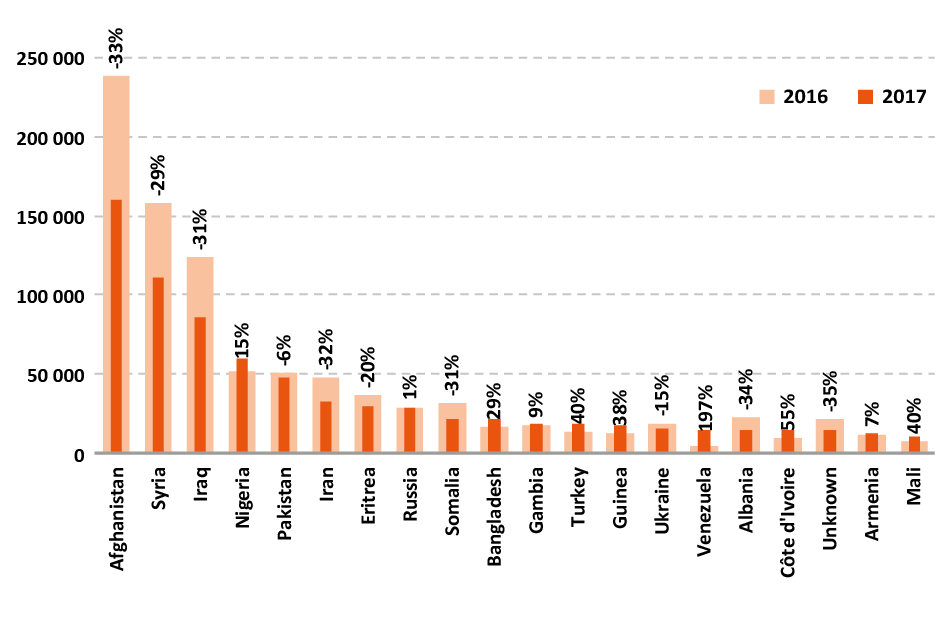

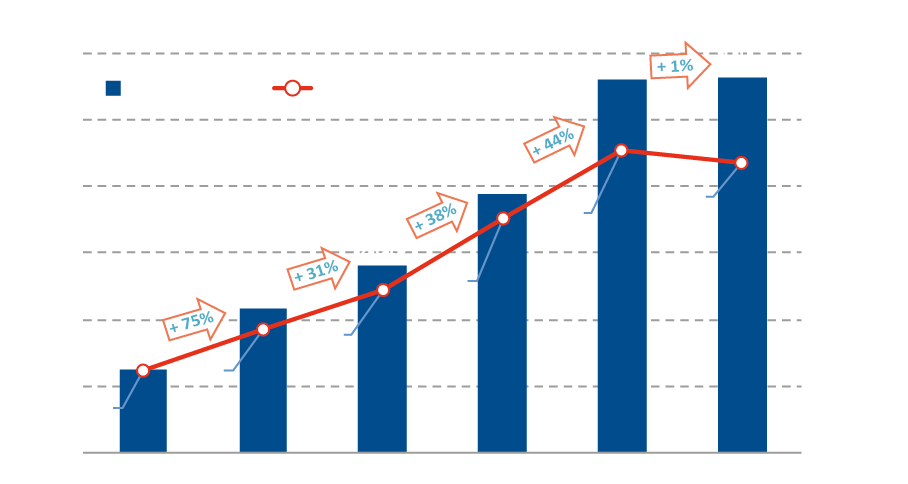

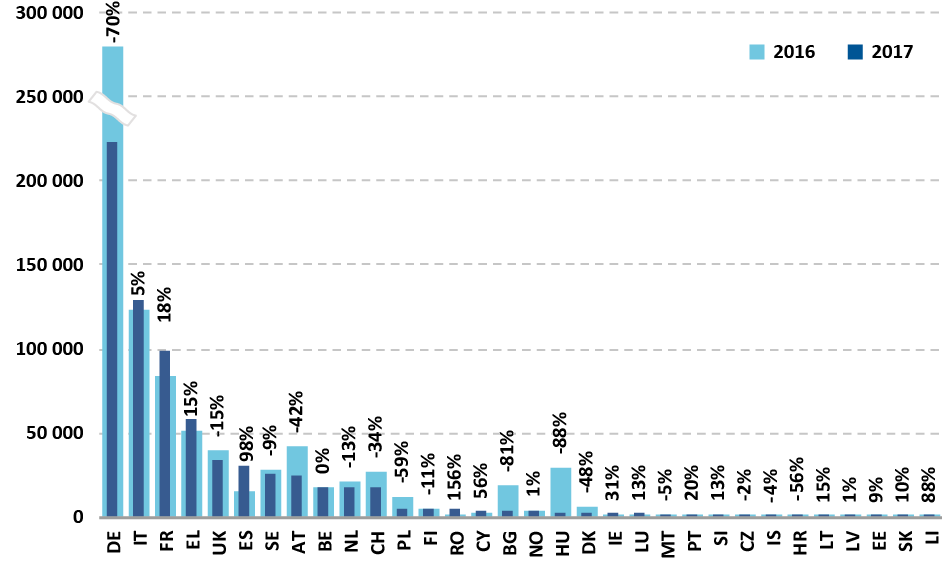

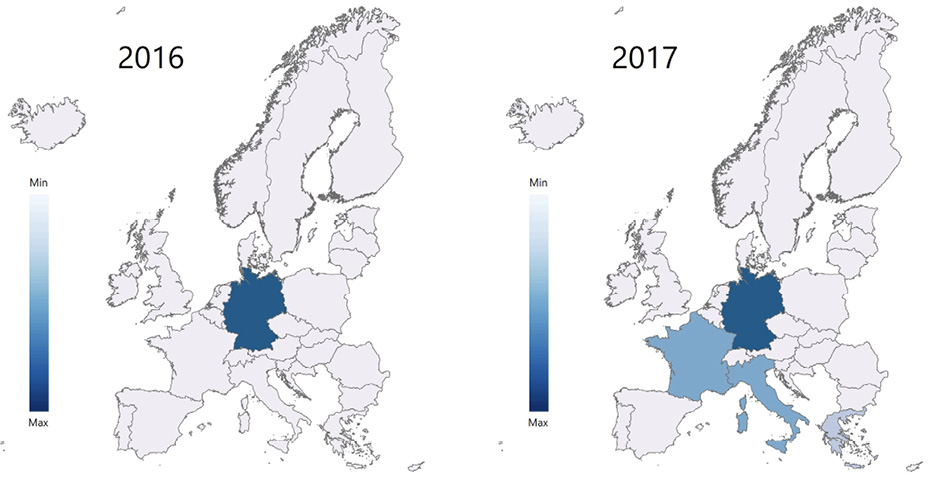

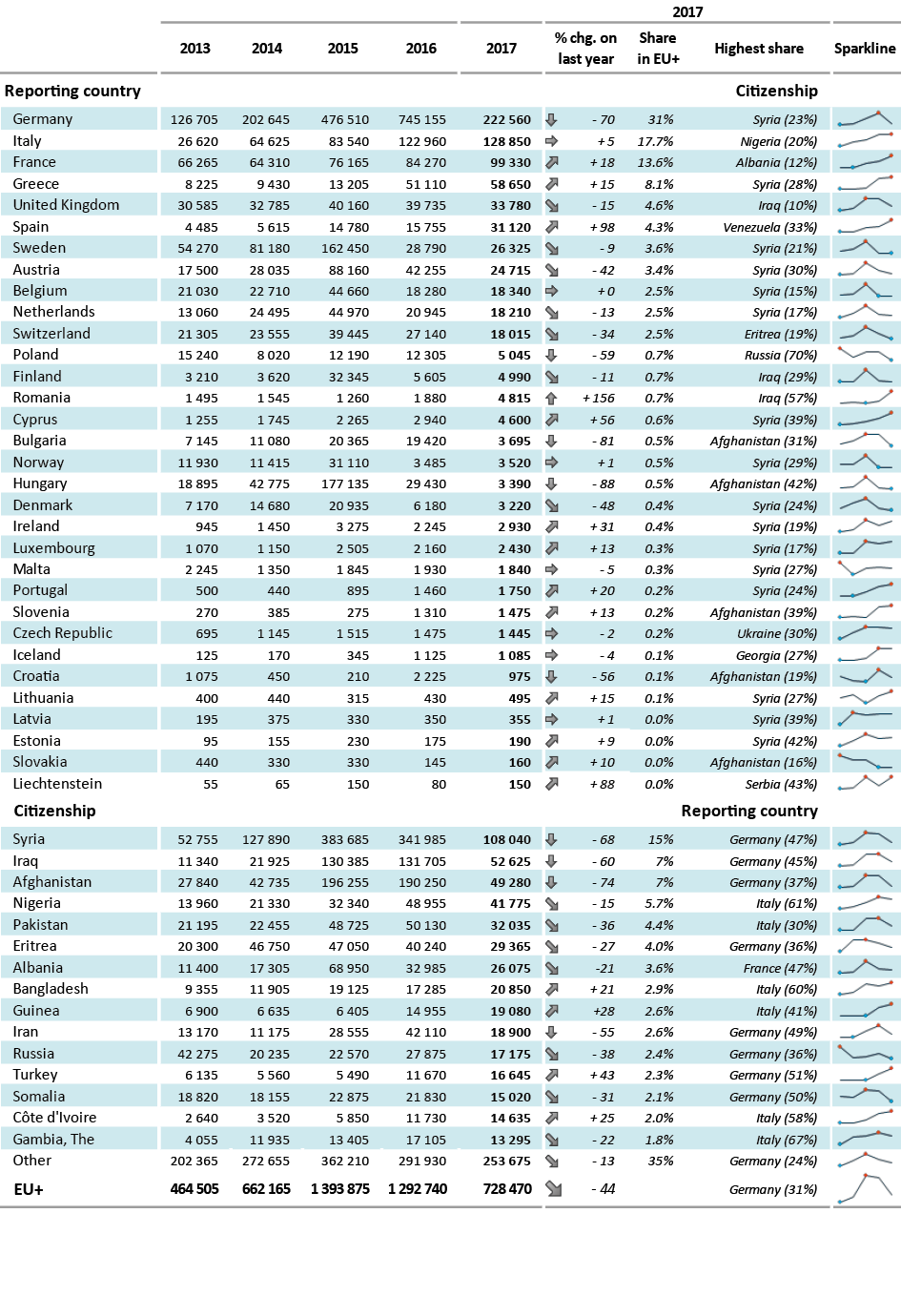

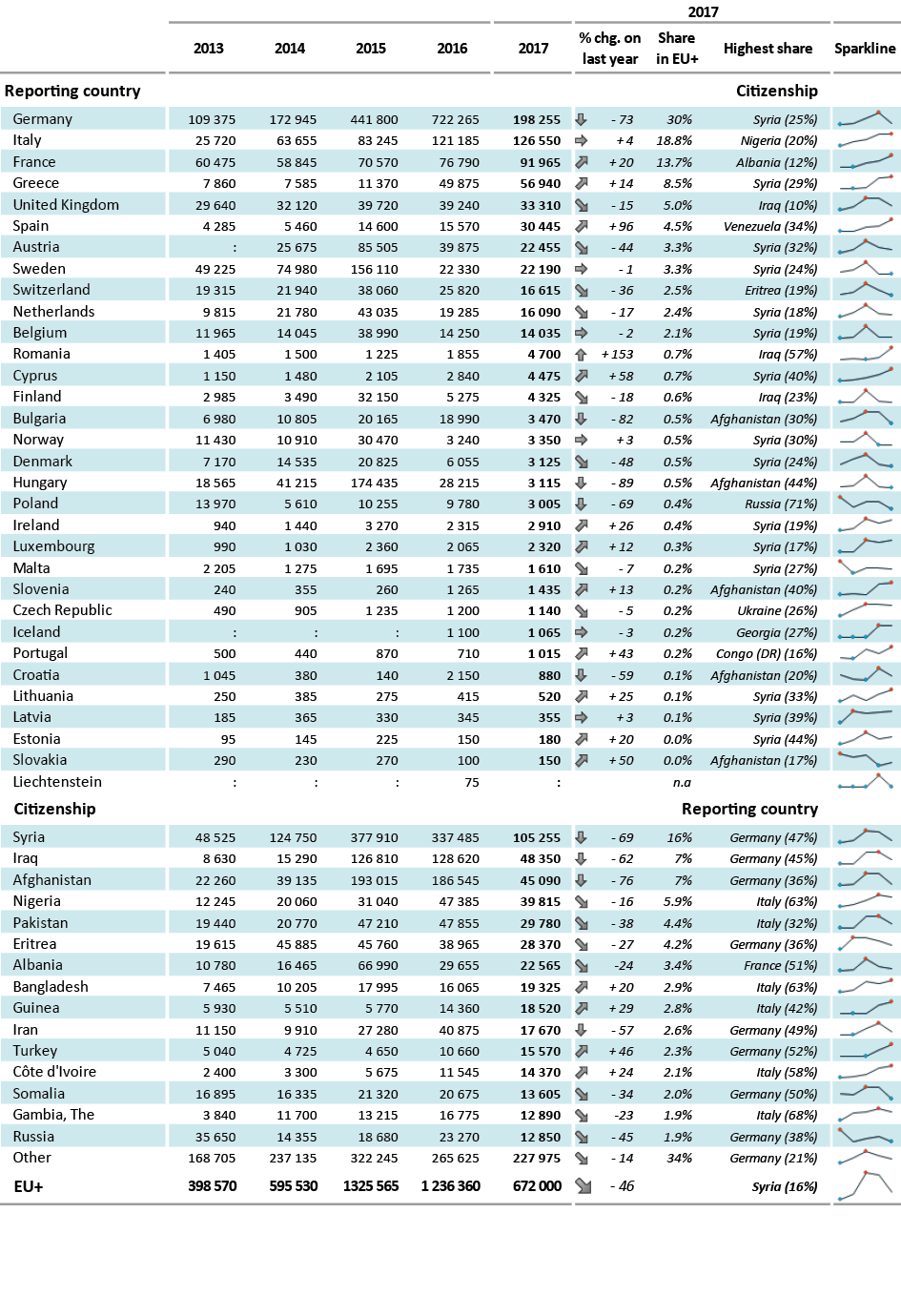

In terms of statistical trends, in 2017, there were 728 470 applications for international protection in the EU+, representing a decrease of 44 % compared to 2016, but remaining at a higher level than prior to the refugee crisis, which started in 2015. Migratory pressure at the EU external borders remained high, but decreased for second consecutive year, mostly at the eastern and central Mediterranean routes, whereas there was an unprecedented upsurge on the western Mediterranean route.

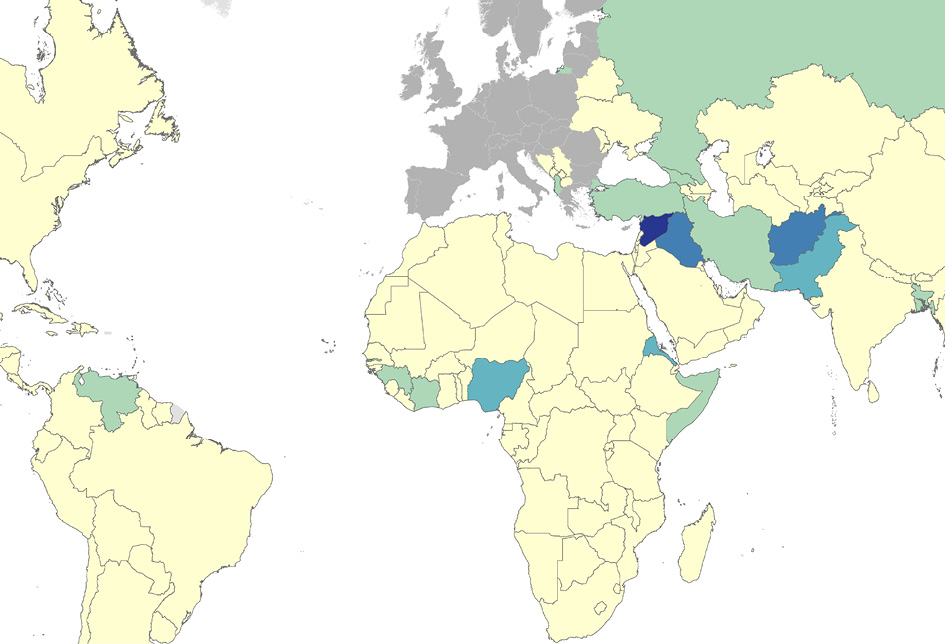

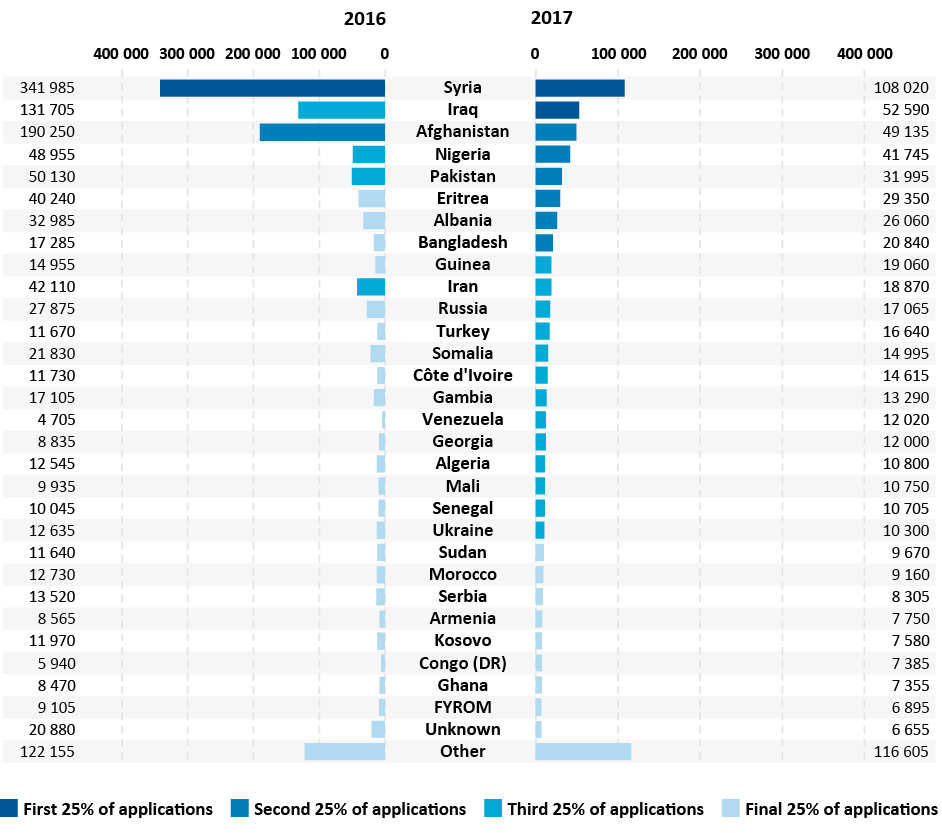

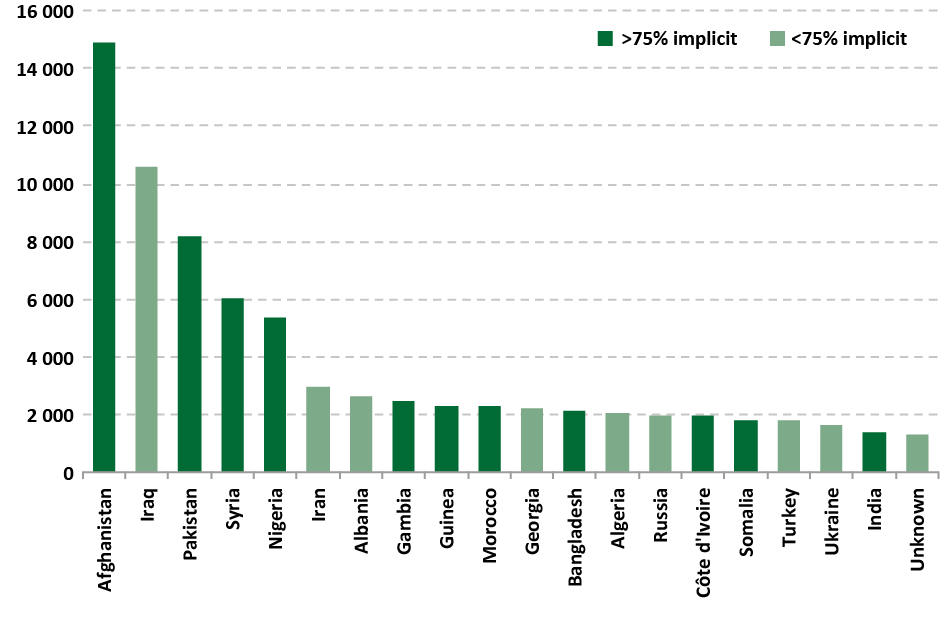

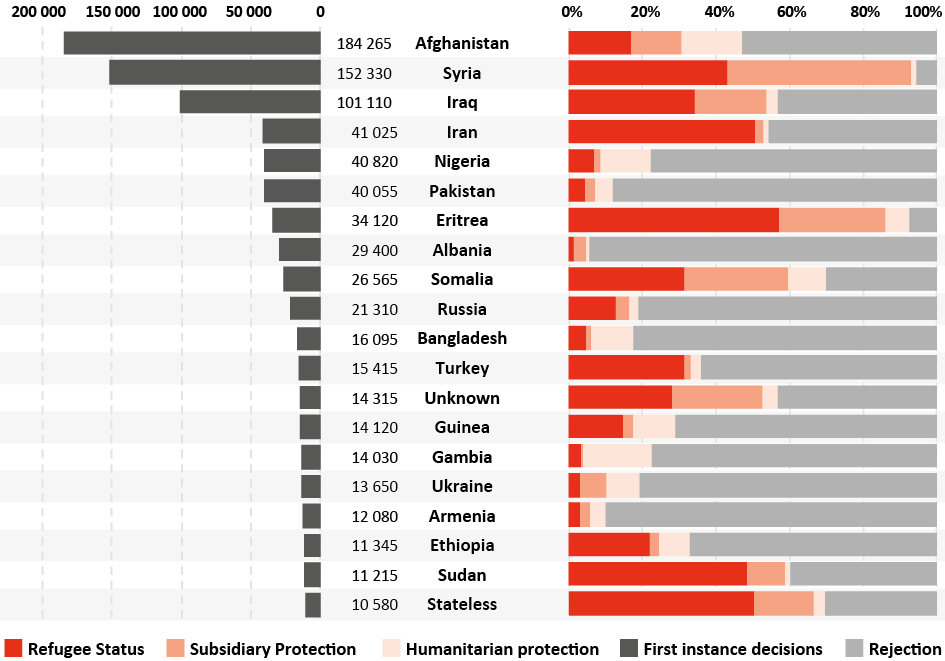

Syria (since 2013), Iraq, and Afghanistan were the three main countries of origin of applicants in the EU+. Approximately 15 % of all applicants originated from Syria, with Iraq ranking second and Afghanistan third, each representing 7 % of all applications in the EU+. These three countries were followed by Nigeria, Pakistan, Eritrea, Albania, Bangladesh, Guinea and Iran.

In Syria’s neighbouring countries, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Turkey, Egypt and other northern African countries, UNHCR indicated that the number of registered Syrian refugees by the end of 2017 amounted to approximately 5.5 million.

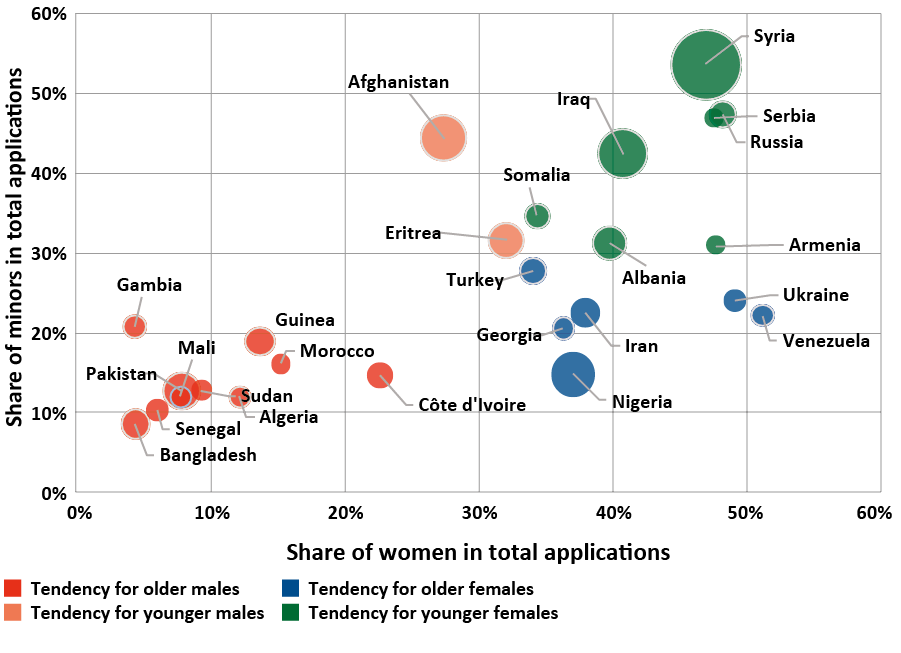

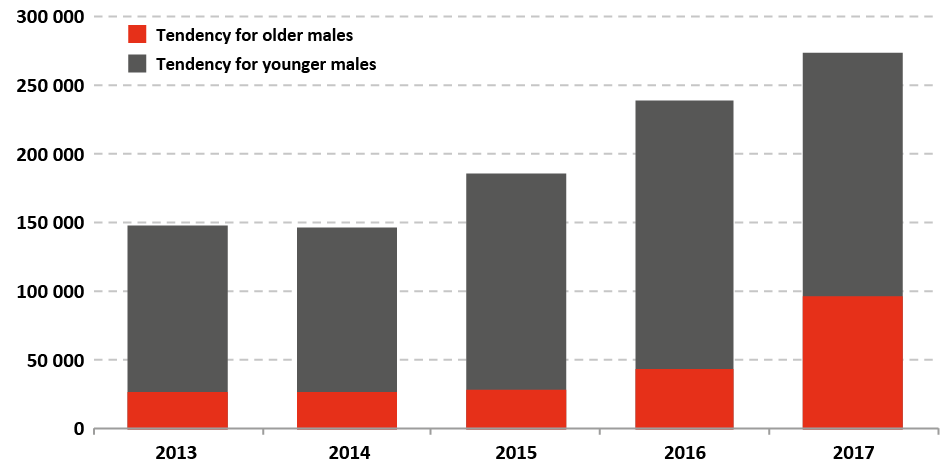

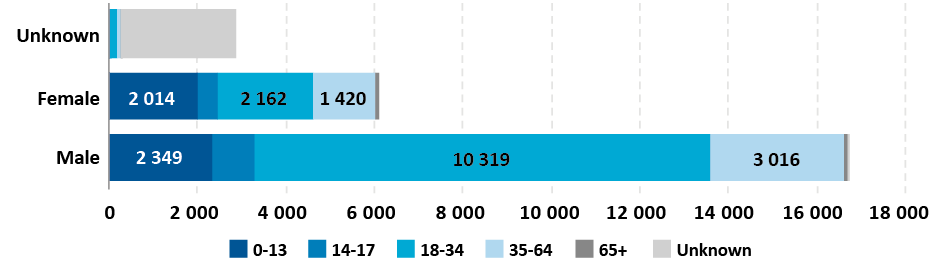

In 2017, similar to 2016, just over two thirds of all applicants were male and a third were female. Half of the applicants were in the age category between 18 and 35 years old, and almost a third were minors.

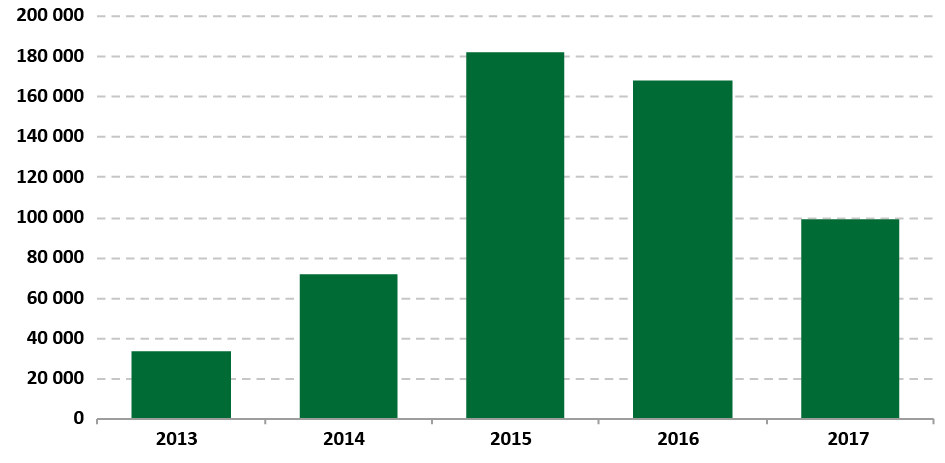

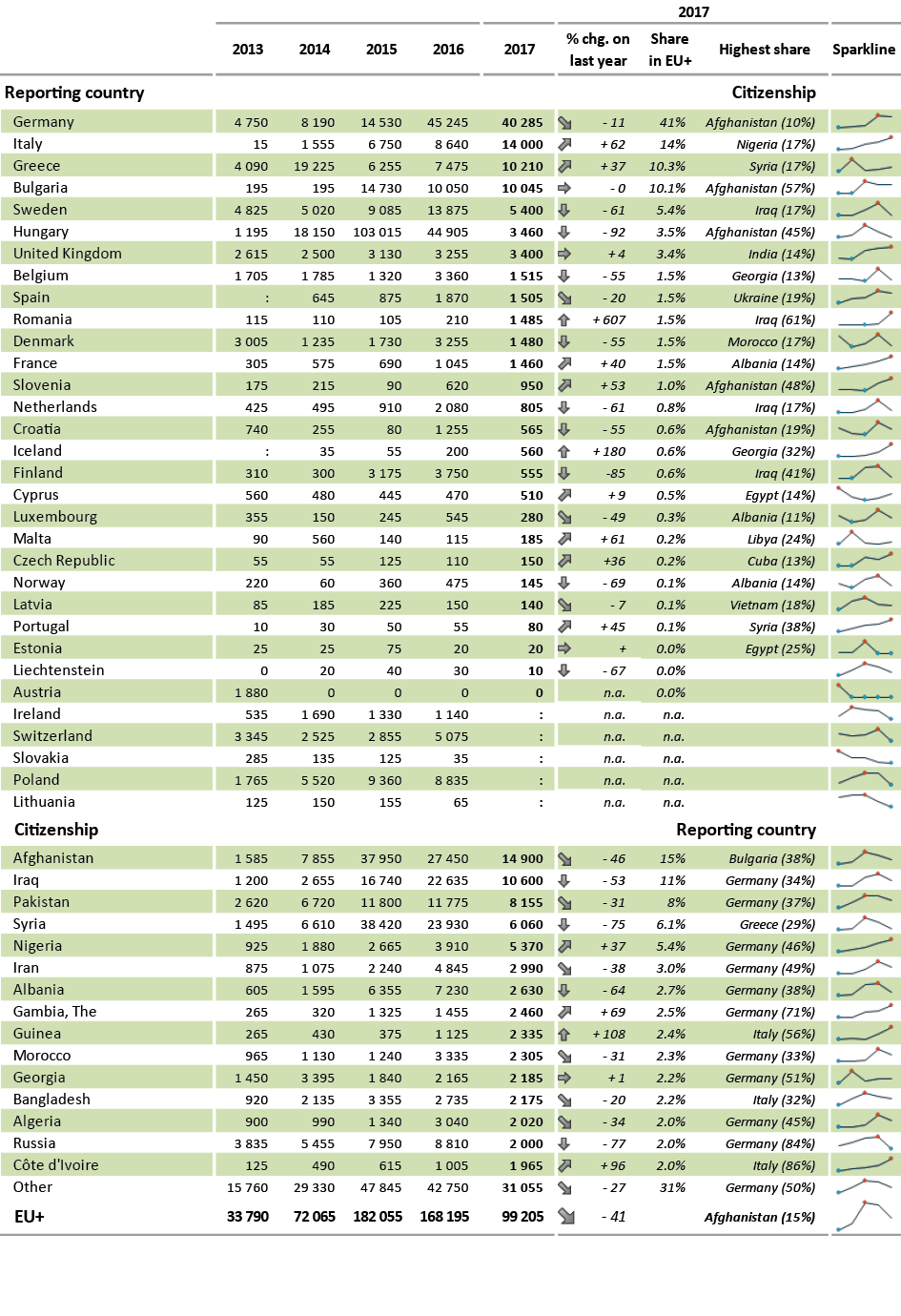

Overall in 2017, some 99 205 applications were withdrawn across EU+ countries, a sizeable decrease of 41 % compared to 2016, when 168 195 applications were withdrawn. The ratio of applications withdrawn to the total number of applications lodged in the EU+ was 14 %, a proportion similar to previous years. According to EASO data, again similar to previous years, most withdrawals were implicit, meaning applicants abandoned the asylum procedure without explicitely informing the authorities.

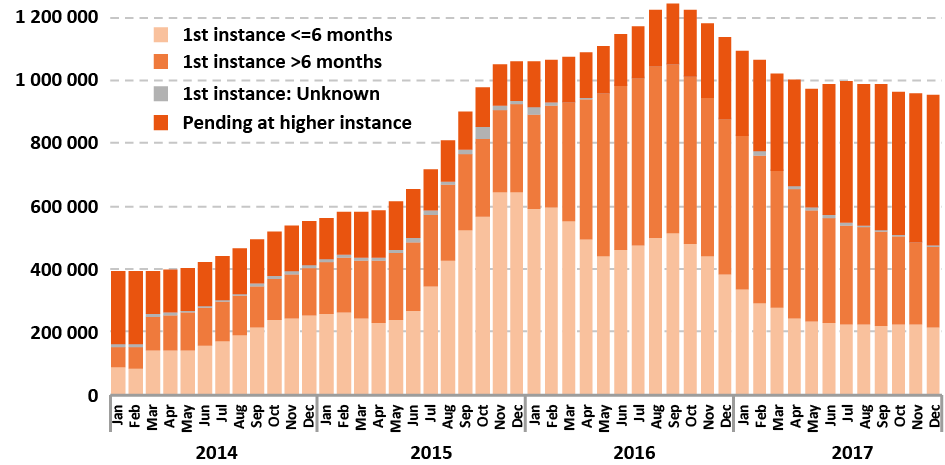

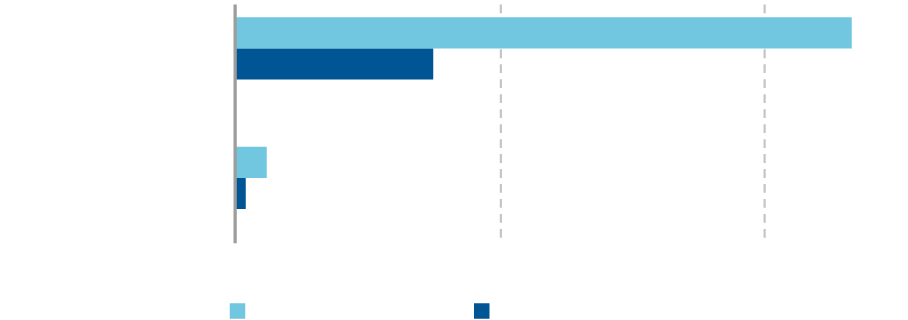

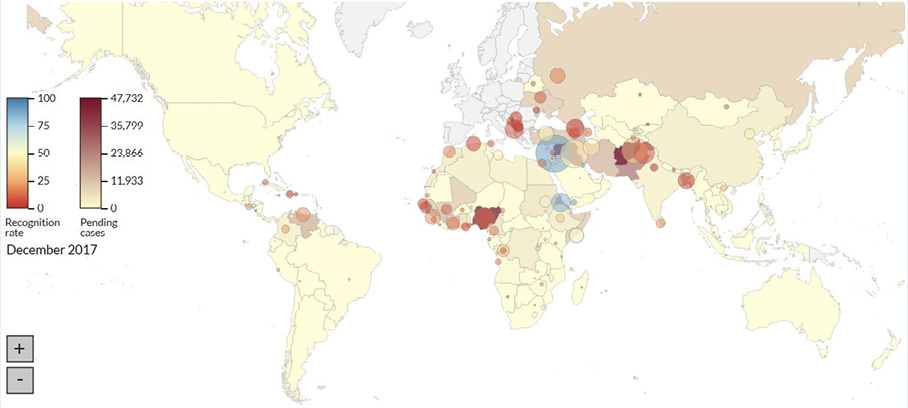

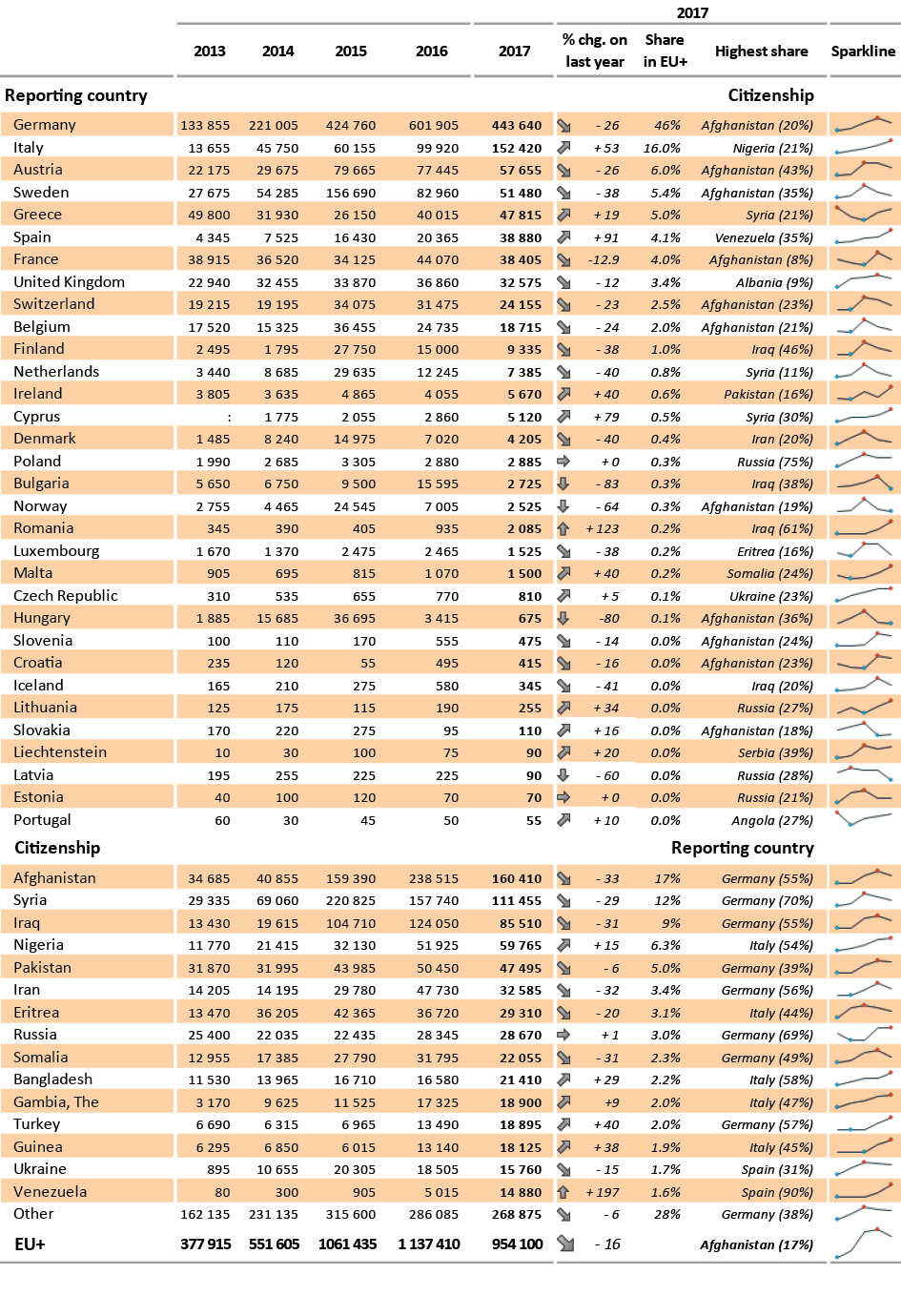

In terms of pending cases, for the first time in several years, at the end of 2017 the stock of pending cases was reduced compared to the year before, while approximately 954 100 applications were awaiting a final decision in the EU+, 16 % fewer than at the same time in 2016. At the end of 2017, just half of all pending cases were awaiting a decision at first instance, whereas an increasing proportion were pending at second or higher instance, which is a new phenomenon. The number of cases awaiting decision at second and higher instance almost doubled since the end of 2016, pointing to the transfer of workload in national systems from the first instance to the appeal and review stage.

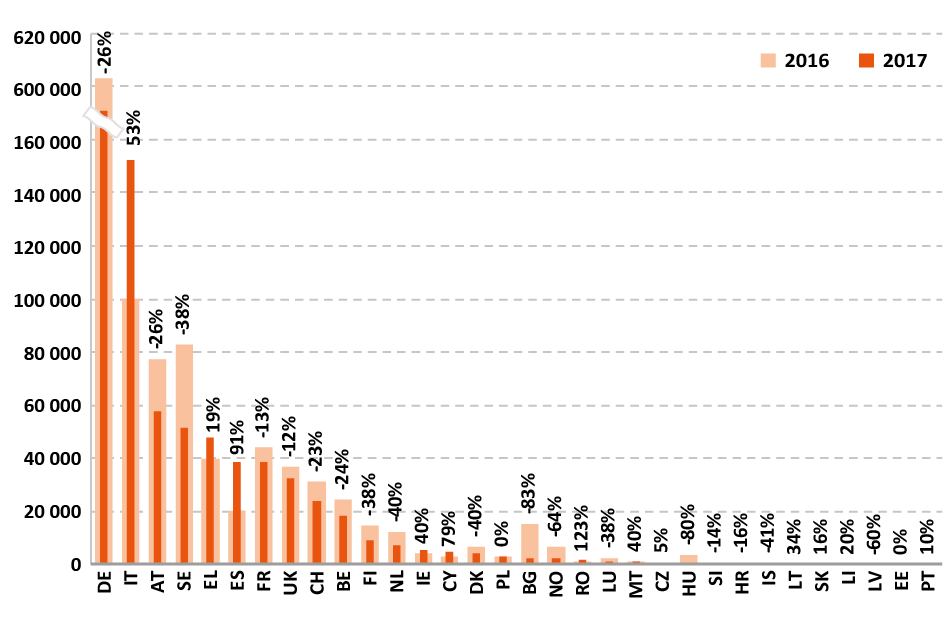

The largest number of applications awaiting a decision concerned Afghans, Syrians and Iraqis. At the end of 2017, most of the pending cases (443 640) were still reported in Germany. However, the stock decreased by more than a quarter compared to 2016. Italy continued to be the second EU+ country in terms of pending cases, while considerable increases occurred in Spain and Greece.

The reduction in the backlog in the majority of the EU+ states was due to a combination of factors, including fewer new applications, coupled with the issuing of more decisions. Specific organisational and policy measures implemented in EU+ states to tackle the problem of heavy processing backlogs also had an impact.

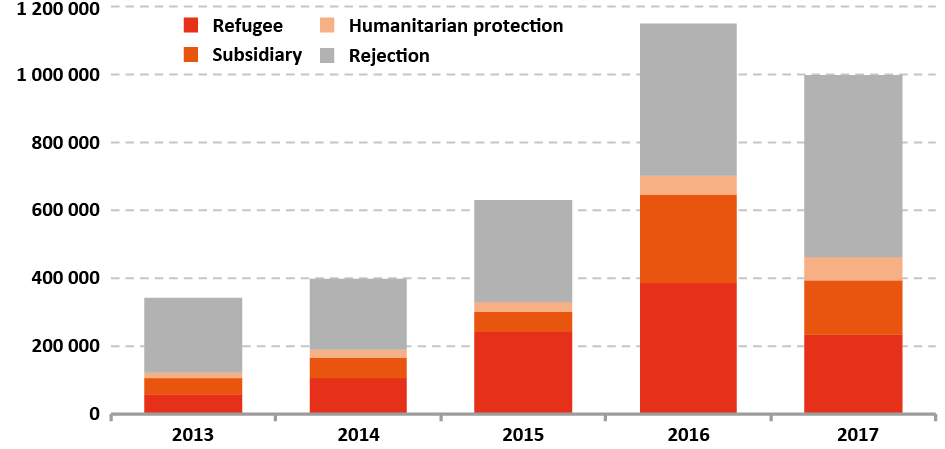

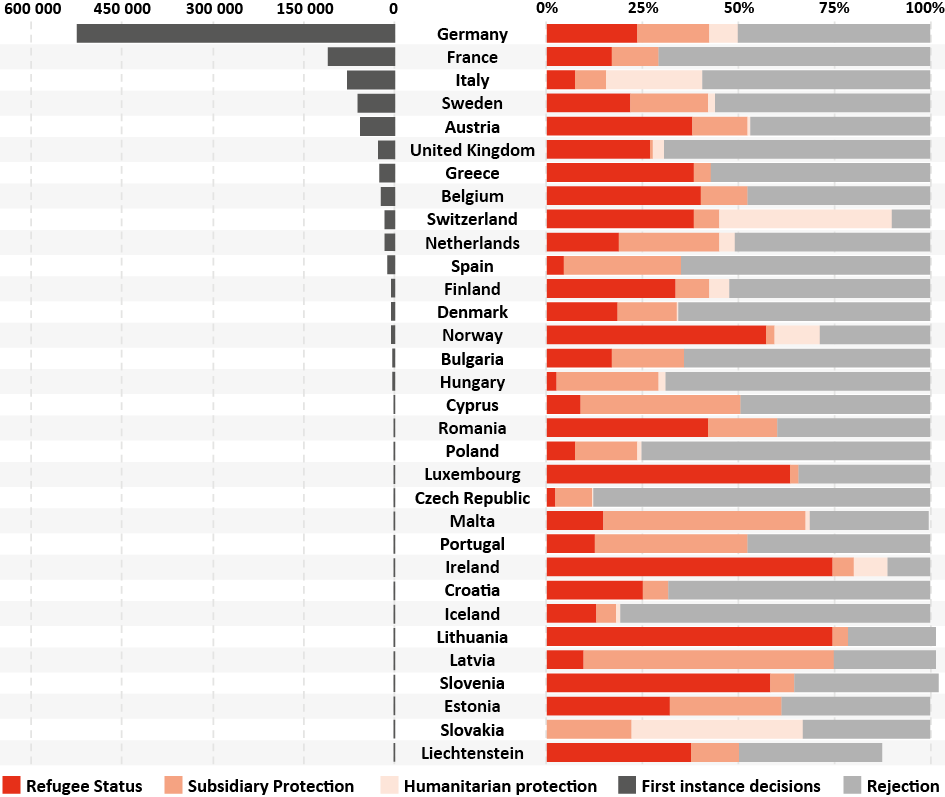

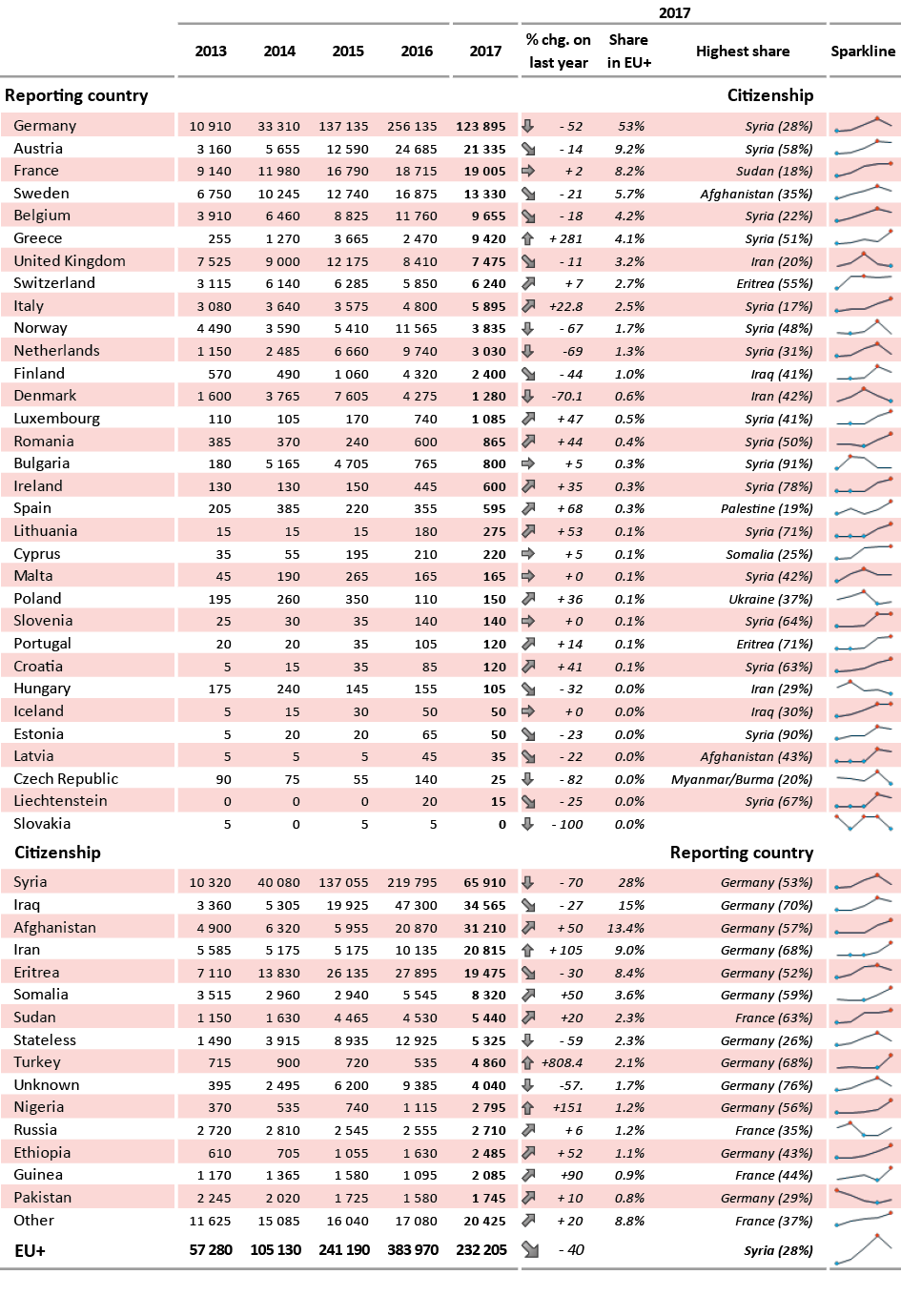

In terms of decisions issued, in 2017, EU+ countries issued 996 685 decisions in first instance, a 13 % decrease compared to 2016. The year-on-year decrease clearly reflects the lower number of applications lodged: 2016 represented a record year in terms of volume of applications for international protection, with EU+ countries intensifying their efforts to deal with a growing backlog.

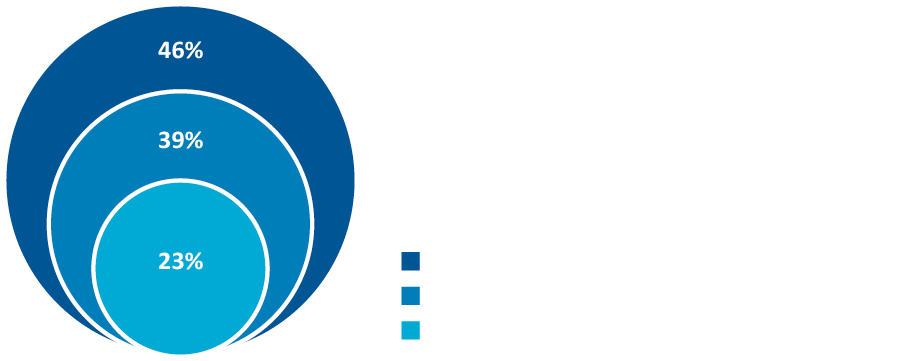

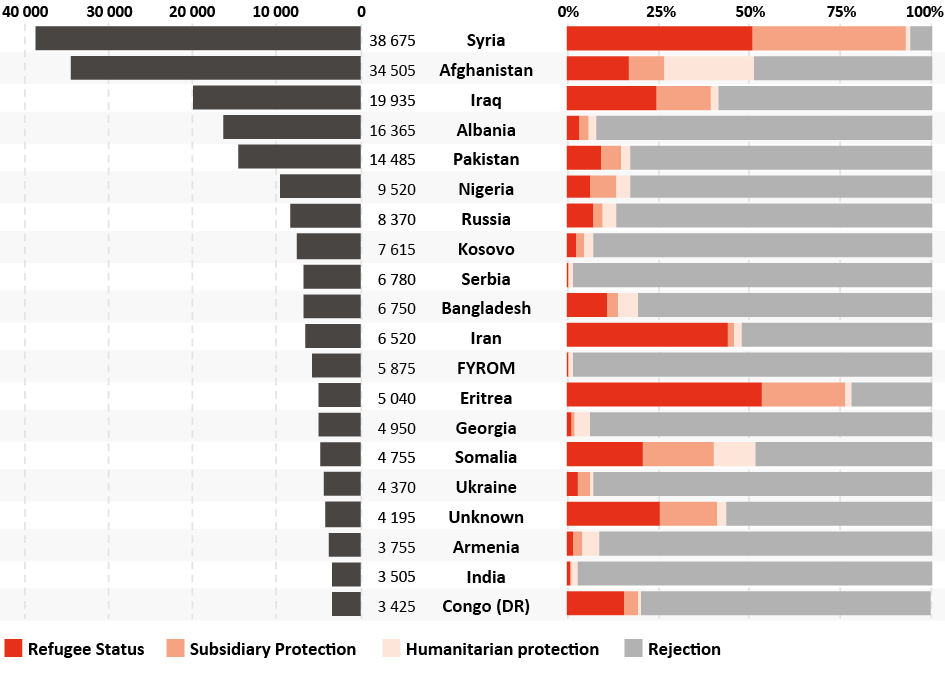

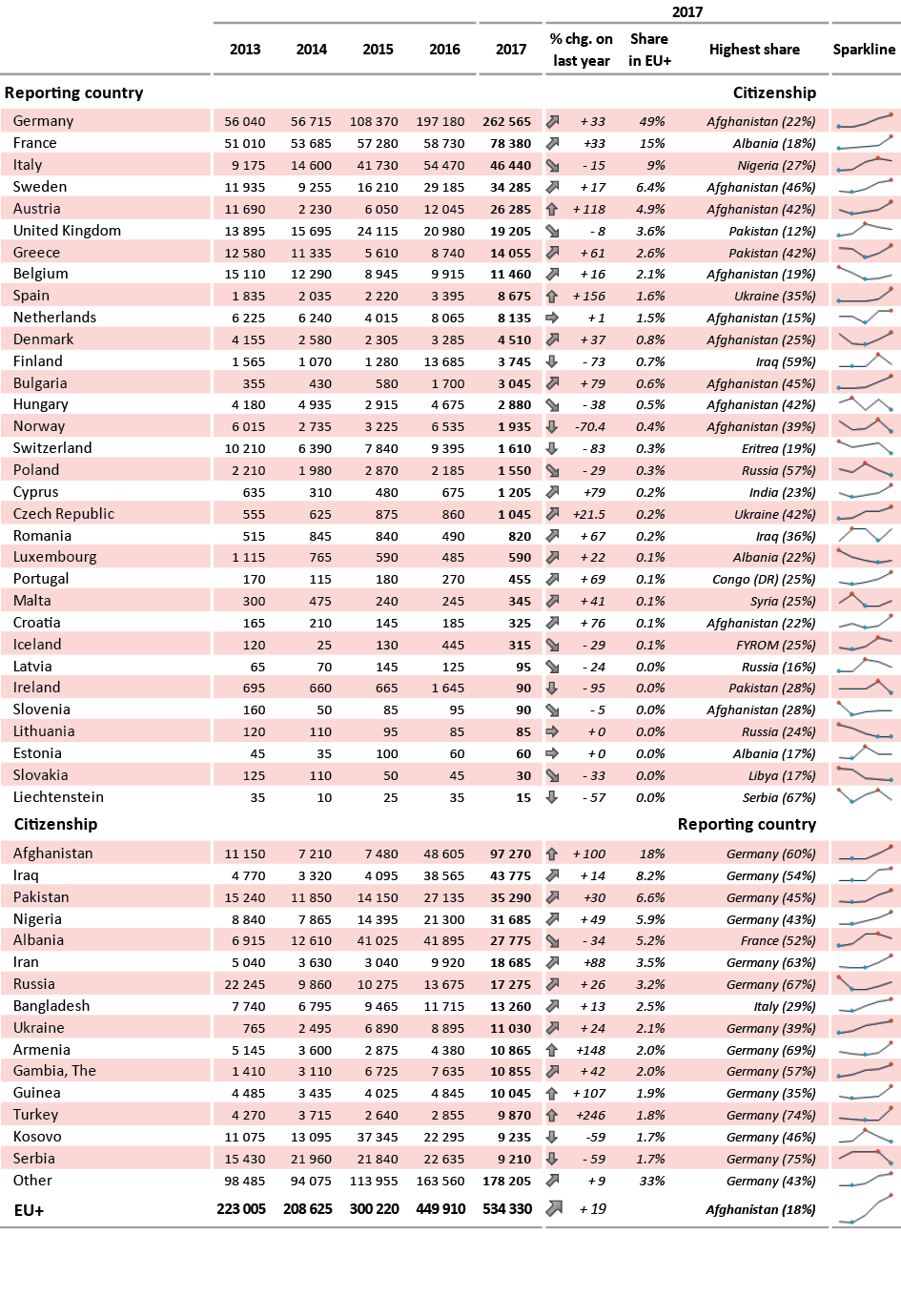

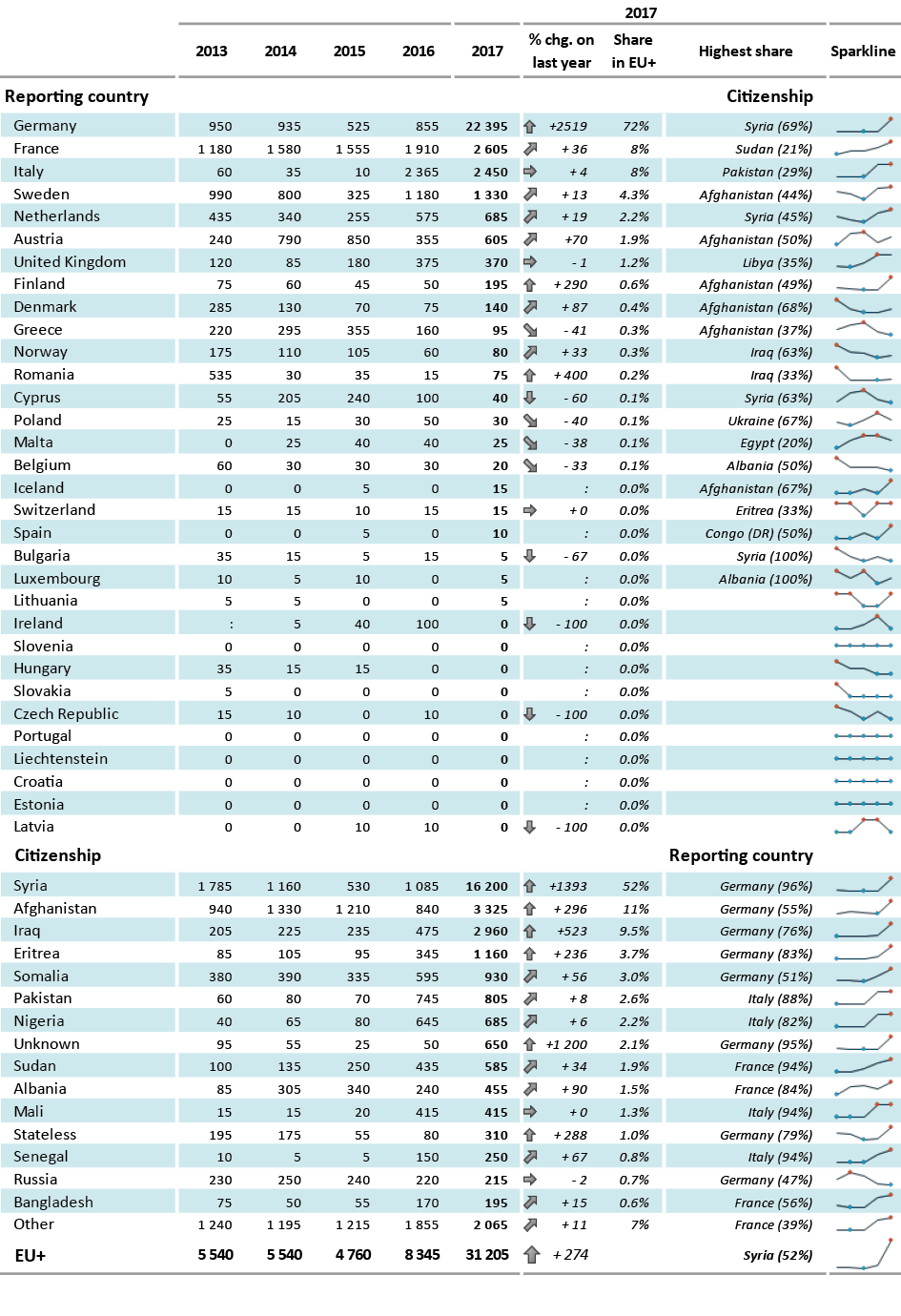

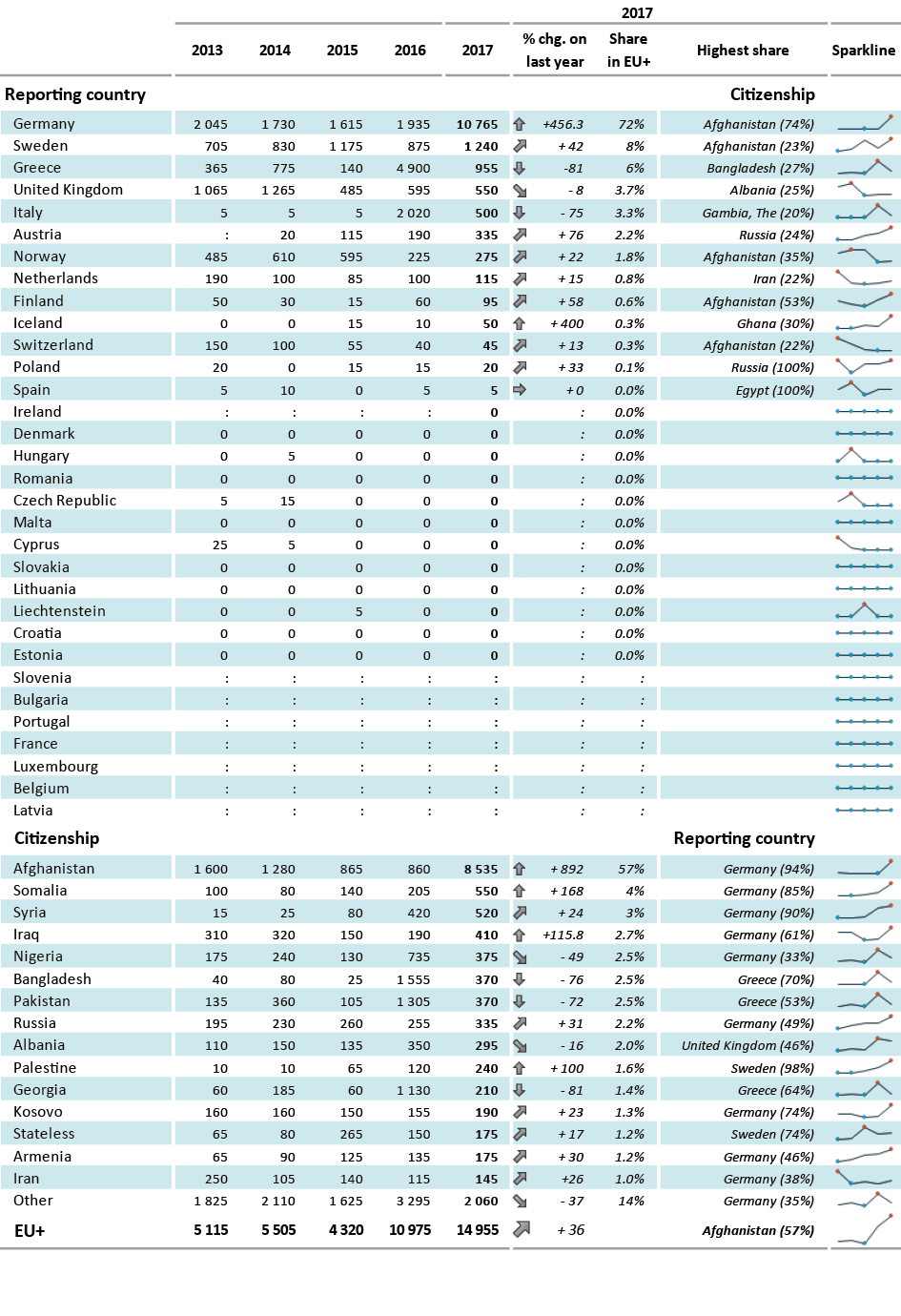

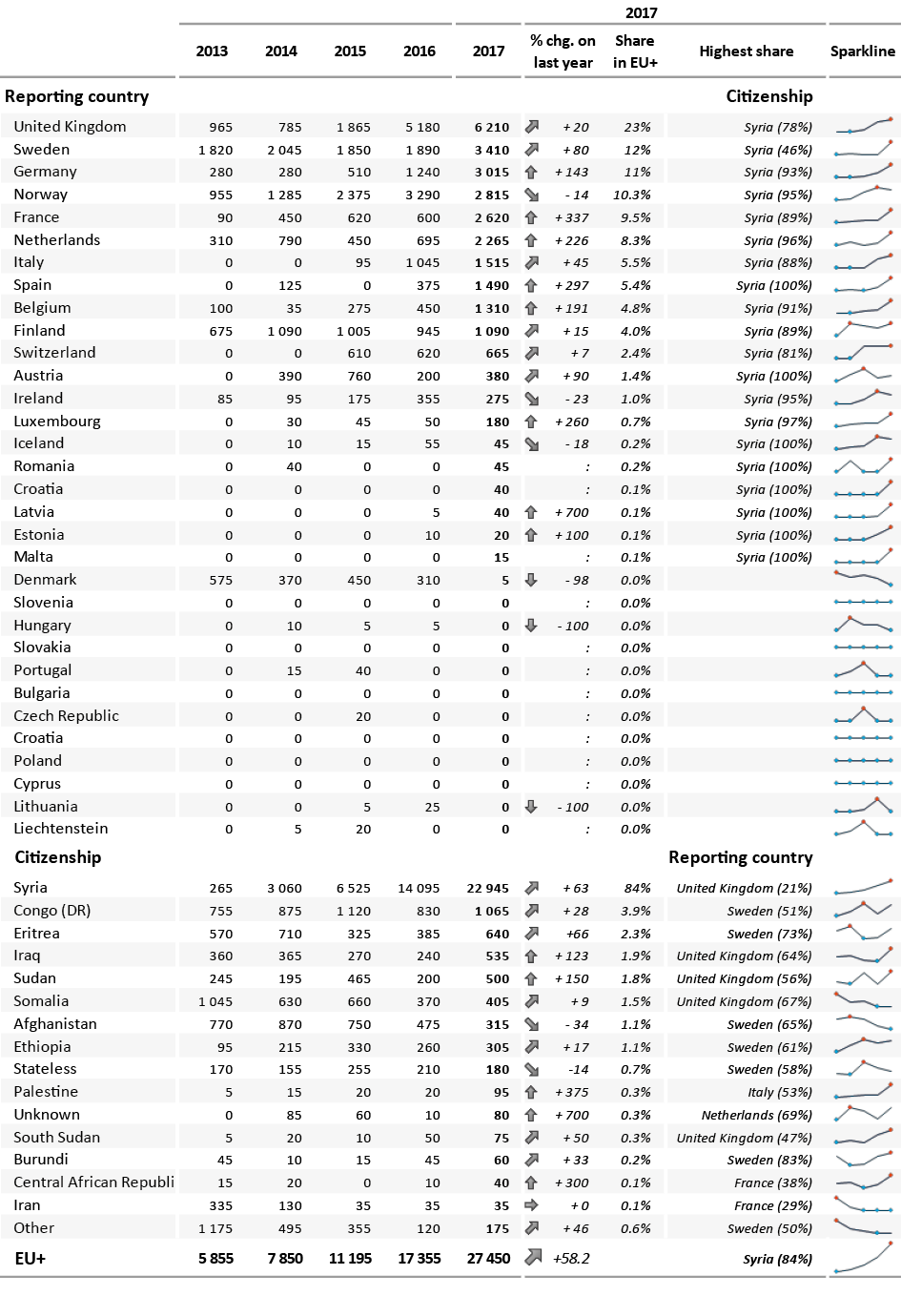

Of all the first instance decisions issued in 2017, nearly half (462 355) were positive, but this overall EU+ recognition rate was 14 percentage points lower than in 2016. Despite fewer decisions issued overall, the number of negative decisions actually increased: from 449 910 in 2016 to 534 330 in 2017. Concerning positive decisions, in 2017 there was a distinct decrease in the share of decisions granting refugee status (down to 50 %, from 55 % in 2016) or subsidiary protection (34 %, from 37 %) with a parallel increase in the proportion of those granting humanitarian protection (15 %, up from 8 %).

This reduction of the EU+ recognition rate to 46 % (dropping by 14 percentage points compared to 2016) is at least partially due to fewer decisions being issued to applicants with rather high recognition rates, combined with more decisions being issued to applicants with rather low recognition rates. While there were fewer decisions issued to applicants from Syria and Eritrea, decisions issued to Afghan, Iranian and Nigerian applicants were considerably more than in 2016.

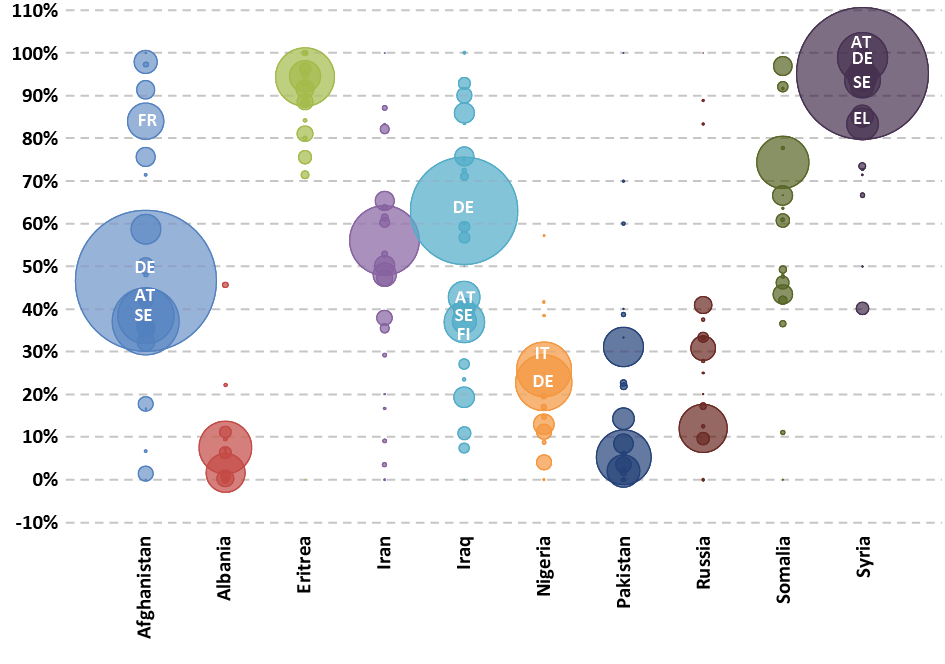

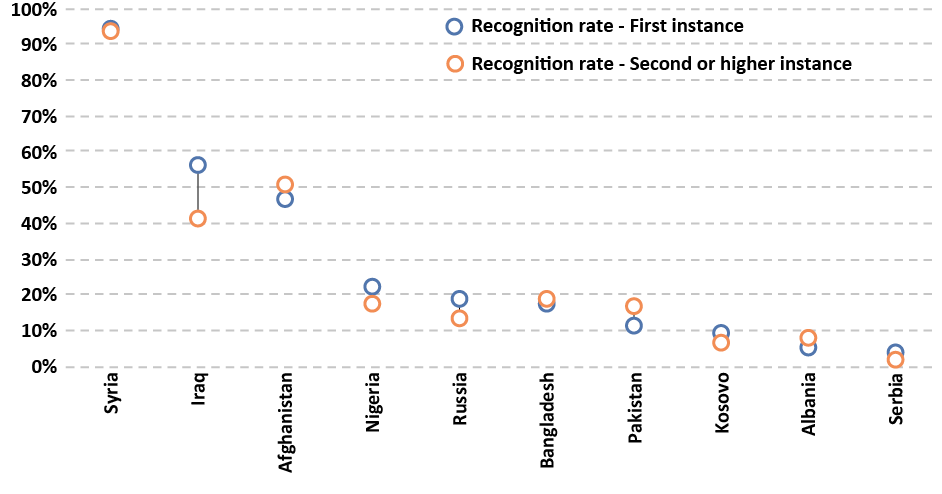

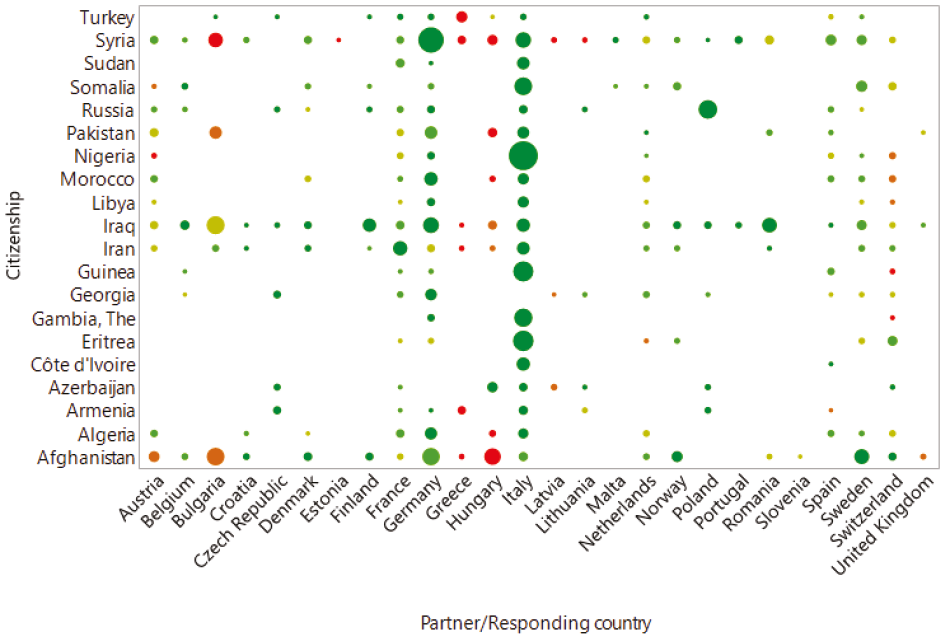

Importantly, recognition rates tend to vary across EU+ countries, at both relatively low and high values of the recognition rates, in particular for applicants from Afghanistan, Iran and Iraq, where the recognition rate ranged between 0 and 100 %. For others, there was relatively more convergence at higher (e.g. Eritrea and Syria) and lower (e.g. Albania and Nigeria) recognition rates.

For individual citizenships, variation in recognition rates among EU+ countries may suggest, to some extent, a lack of harmonisation in terms of decision-making practices (due to a different assessment of the situation in a country of origin, a different interpretation of legal concepts, or due to national jurisprudence). However, it may also indicate that even among applicants from the same country of origin, some EU+ countries may receive individuals with very different protection grounds, such as, for example, specific ethnic minorities, people from certain regions within a country, or applicants who are unaccompanied children.

As regards decisions issued in appeal or review, in 2017, EU+ countries issued 273 960 decisions at second or higher instance, a 20 % increase compared to 2016, reinforcing an upward trend in the number of decisions, which has been noticeable since 2015. Three quarters of all decisions at second or higher instance were issued in Germany (58 % of the EU+ total), France (12 %), and Sweden (7 %). More specifically, Syrians received four times as many (38 675), Afghans three times as many (34 505) and Iraqis almost three times as many (19 935) decisions. In contrast, in 2016 a third of all decisions issued in appeal were received by applicants of three Western Balkan countries (Albania, Kosovo and Serbia), with much lower recognition rates.

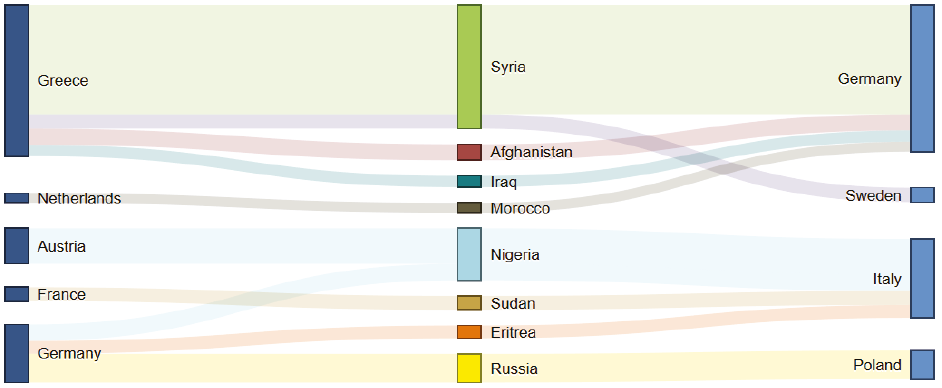

For the functioning of the Dublin system in 2017, a number of developments can be reported on the basis of EASO data, which indicated an increase in decisions on Dublin requests. For every received decision on a Dublin request in 2017 there were close to five applications lodged in the pool of countries reporting on this Dublin indicator, which may imply that a considerable number of applicants for international protection pursue secondary movements in the EU+ countries. In 2017, most decisions were taken in a small group of countries. Italy and Germany were the partner countries for almost half of all responses, followed at a distance by Bulgaria, Sweden, France, and Hungary. The overall acceptance rate for decisions on Dublin requests in 2017 was 75 %; however, the acceptance rate varied considerably between responding countries. Decisions were most commonly reached on Dublin requests for citizens of Afghanistan (11 % of the total), Syria (8 %), Iraq (8 %), and Nigeria (6 %). EASO data also indicated that about two thirds of these decisions were in response to ‘take back’ requests, which means that the majority of decisions relate to cases in which a person lodges an application in one EU+ country and afterwards moves to another country. In 2017, Article 17(1) of the Dublin Regulation, known as one of the discretionary clauses, was evoked nearly 12 000 times (more than half of these cases were applied by Germany or Italy). In 2017, the 26 reporting countries implemented just over 25 000 transfers, an increase of a third compared to 2016. Three quarters of all transfers in 2017 stemmed from five EU+ countries: Germany, Greece, Austria, France, and the Netherlands. More than half of the transferees were received by Germany and Italy.

In general, main developments in EU+ countries with regard to Dublin procedure reflected the volume of cases that needed to be processed. Like in 2016, in 2017, the suspension (either full or partial) of Dublin transfers to Hungary and Bulgaria was also noted. On 8 December 2016, the European Commission recommended measures for strengthening the Greek asylum system as well as a gradual resumption of transfers to Greece for certain categories of asylum applicants) and a number of Dublin Member States sent in 2017 transfer requests to Greece following the recommendation.

A number of EU+ countries amended their legislation concerning international protection. These included significant changes in Austria, Belgium, Hungary and Italy, while other countries also amended their legislation in diverse areas, including changes to the national lists of safe countries of origin.

Many EU+ countries also made changes as regards internal restructuring and transfer of competencies among various entities in national asylum administration, including the creation of specialised task forces to tackle thematic issues.

Significant efforts of EU+ countries were also aimed at ensuring the integrity of their national systems, by preventing and combating unfounded claims for international protection and detection of security concerns. This was facilitated by the implementation of advanced identification and registration systems, supported by modern technology, and the implementation of procedures of age assessment, an area where many developments were noted in 2017.

Various initiatives were undertaken by EU+ countries in 2017 to improve the efficiency of the asylum process, i.e. to conduct procedures for international protection while using the available time and resources in the optimum way, speeding up award of protection in justified cases and avoiding lengthy procedures for cases with no merit. The main trends concerned digitalisation and introduction of new technologies (information system, databases, videoconferencing for interviews and interpretation), that also helped in exchange of information among various actors. Similar objectives were pursued with measures toward better organising asylum systems by setting up specialised processing centres, such as in Germany, and by using measures for the distribution of cases, channelling certain categories through specifically dedicated channels. Measures also included prioritisation and fast-track procedures.

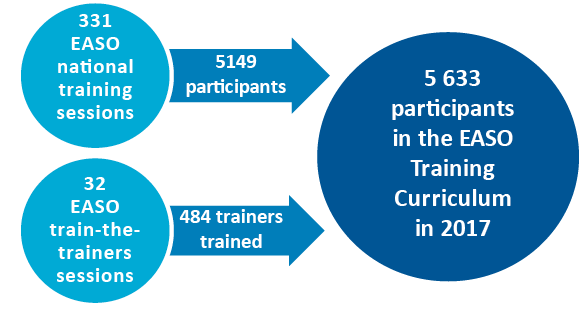

In addition, to maintain and enhance quality, EU+ countries implemented quality assurance mechanisms, developed guidance materials, and offered capacity-building activities to staff members, in particular as regards complex areas of asylum, such as issues relating to vulnerability. These measures were supplemented by rich and comprehensive training offered by EASO. Despite these efforts, civil society and UNHCR underlined the need to continue pursuing systematically and in a consistent way the improvement of quality in daily practice.

The European Resettlement Scheme, launched at the Justice and Home Affairs Council on 20 July 2015, came to an end on 8 December 2017. By then, 19 432 people in need of international protection had been resettled under the scheme to 25 Member and Associated States, which amounts to 86 % of the 22 504 resettlements initially pledged and agreed upon by the parties.

The Commission issued a Recommendation on 27 September 2017 on enhancing legal pathways for persons in need of international protection, thus introducing a new scheme that aims at resettling at least 50 000 persons by 31 October 2019. By 26 May 2018, over 50 000 pledges had been already made by 19 Member States, making it the largest EU collective engagement on resettlement to date. So far, almost 2 000 persons have already been resettled under this new scheme.

Meanwhile, the resettlement scheme under the 1:1 mechanism of the EU-Turkey Statement also continued to be implemented, with 12 476 persons resettled to 16 Member States since it came into force on 4 April 2016.

Under these EU joint resettlement schemes, people have been and will be resettled mainly from Turkey, Jordan and Lebanon. The new scheme of 27 September 2017 will have a particular focus on resettling from the African countries along the Central Mediterranean route.

Throughout 2017, EU+ countries also noted many developments in national resettlement programmes, building their experience and capacity.

At the same time, EASO continued delivering on its mandate by facilitating practical cooperation among Member States and providing support to countries, whose asylum and reception systems were under pressure, that is, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Italy and Greece. EASO also enhanced its dialogue with civil society, organising thematic meetings on key areas of interest (operational support to hotspots and relocation, provision of information). EASO Early warning and Preparedness System expanded, delivering an analytical portfolio based on standardised data on the asylum situation in the EU+, which the EPS community of Member States shared with EASO on a weekly and monthly basis.

Functioning of the CEAS

Important developments were noted in main thematic areas of the Common European Asylum System:

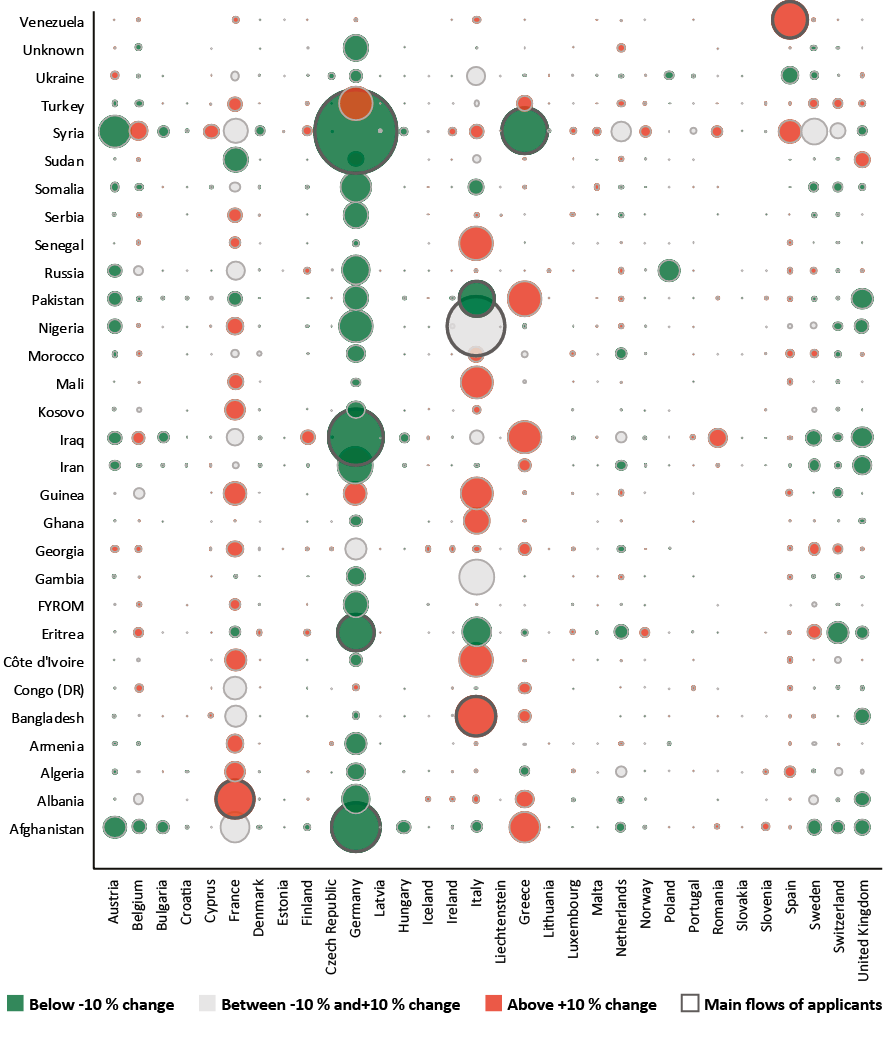

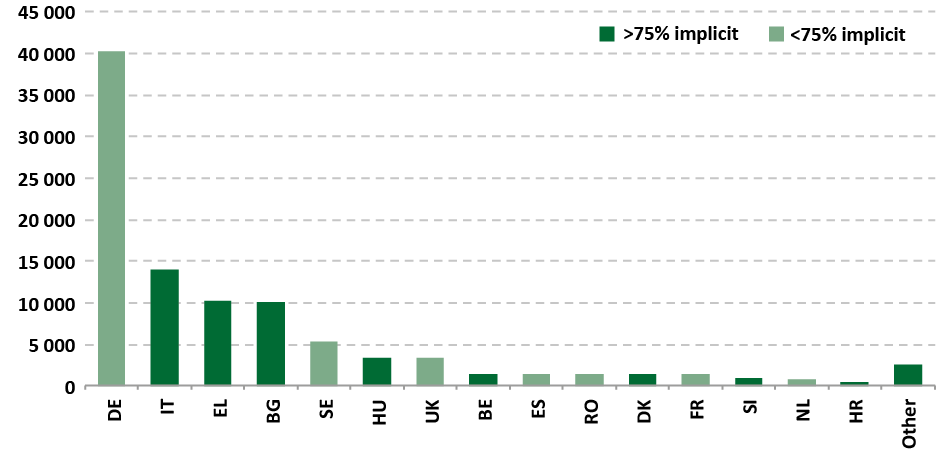

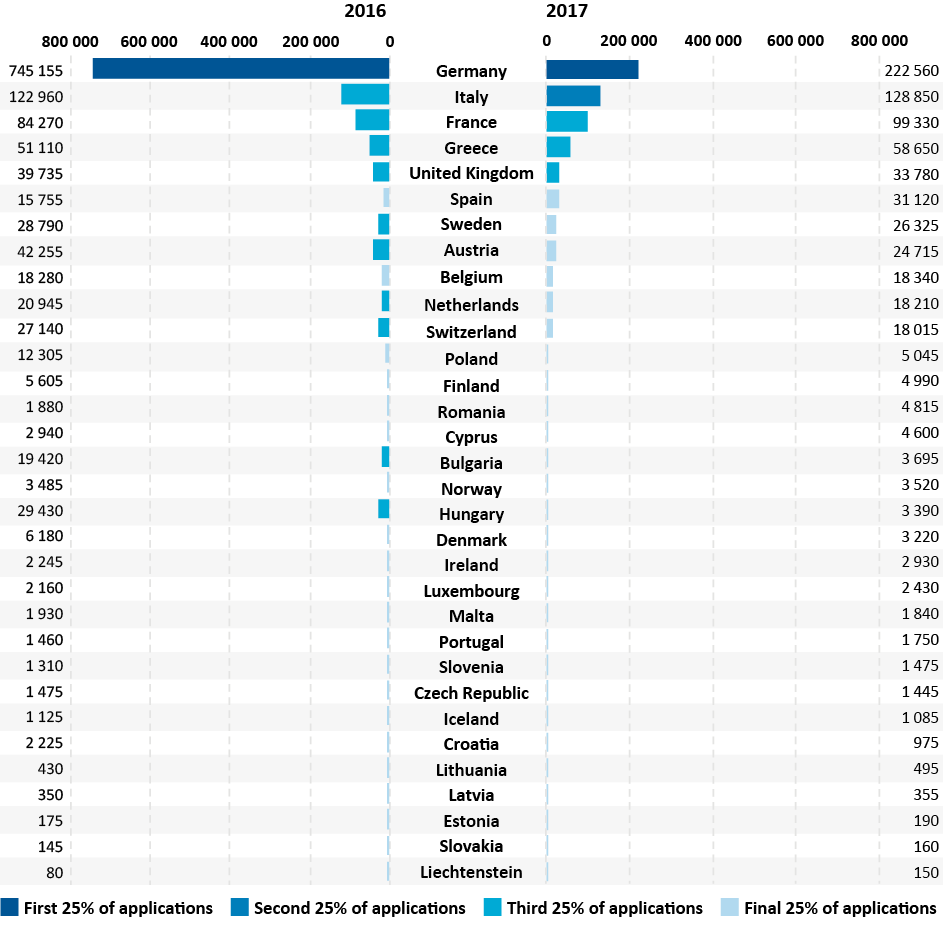

As regards access to procedure, in 2017, the main receiving countries for asylum applicants were Germany, Italy, France, Greece and the United Kingdom. The top four remained the same as in 2016, whereas the United Kingdom replaced Austria as the fifth main receiving country. These five countries jointly accounted for three quarters of all applications lodged in the EU+.

Germany was the main receiving country for the sixth consecutive year. Despite a 70 % decrease in applications lodged in 2017 compared to 2016, its total of 222 560 applications was almost double that of any other receiving country. Italy was the second main receiving country, with 128 850 applications. France followed with a total over 100 000 applications. In terms of country share, Germany alone accounted for 31 % of all applications lodged in the EU+ in 2017. In 2016, however, Germany’s share in the total was at 58 %, almost twice as large. At the same time, the proportion of applicants in the other main receiving countries, in particular Italy, France, Greece, the United Kingdom and Sweden, almost doubled between 2016 and 2017. Greece was the country with the highest proportion of applicants to the number of inhabitants.

While several EU+ countries continued in 2017 to use temporary reintroduction of border control (when necessary) at internal Schengen borders, civil society reported on limited access to the territory including the occurrence of pushbacks in several Member States stressing the need to ensure effective access to protection to those in need. Important developments were related to a swift and efficient registration process, which assisted in increasing efficiency at later stages of the procedure. An example was registration in Greece of applicants previously pre-registered in the summer of 2016 at the time of mass influx.

Access to procedure has also been given through dedicated channels, where persons fulfilling certain criteria were brought to the territory of EU+ countries in an organised manner, such as humanitarian admission mechanisms implemented by several countries. These included humanitarian corridors, as well as humanitarian visa and family reunification programmes, which constitute a legal pathway to Europe for migrants.

In order to be able to fully communicate their protection needs and personal circumstances, and to have them comprehensively and fairly assessed, persons seeking international protection need information regarding their situation. Both EU+ countries’ national administrations and civil society implemented a wide range of information initiatives at all stages of the asylum process, employing a broad variety of means of communication, using social medial and smartphone applications.

Civil society emphasised the need to ensure that information is available and is suited to the needs of its target groups, especially as regards vulnerable individuals. On a related issue, in terms of legal assistance and representation, developments in EU+ countries during 2017 were diverse with some countries broadening the scope or taking steps toward enhancing effectiveness of legal assistance, and others reducing availability of aid. In addition, a number of challenges were identified in the area of legal assistance and representation by civil society actors operating in the field.

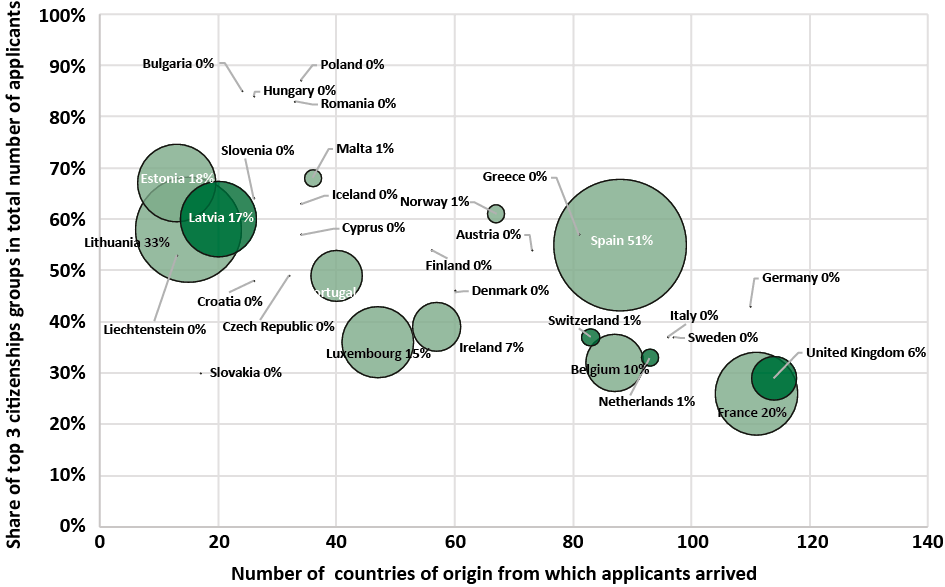

Both information provision and legal assistance are catalysed by effective interpretation, which is an equally important factor in the procedure for international protection. Effective interpretation ensures proper communication between the applicant and the authorities at every step of the process, including access to asylum procedure, application, examination, and appeal stage. Overall, in 2017, EU+ countries received applications from nationals of 54 different countries of origin, as opposed to 35 in 2016, which points to the ever-increasing challenges encountered to secure interpretation services for more and more different languages. That prompted a wider use of technical measures to facilitate interpretation in the asylum process.

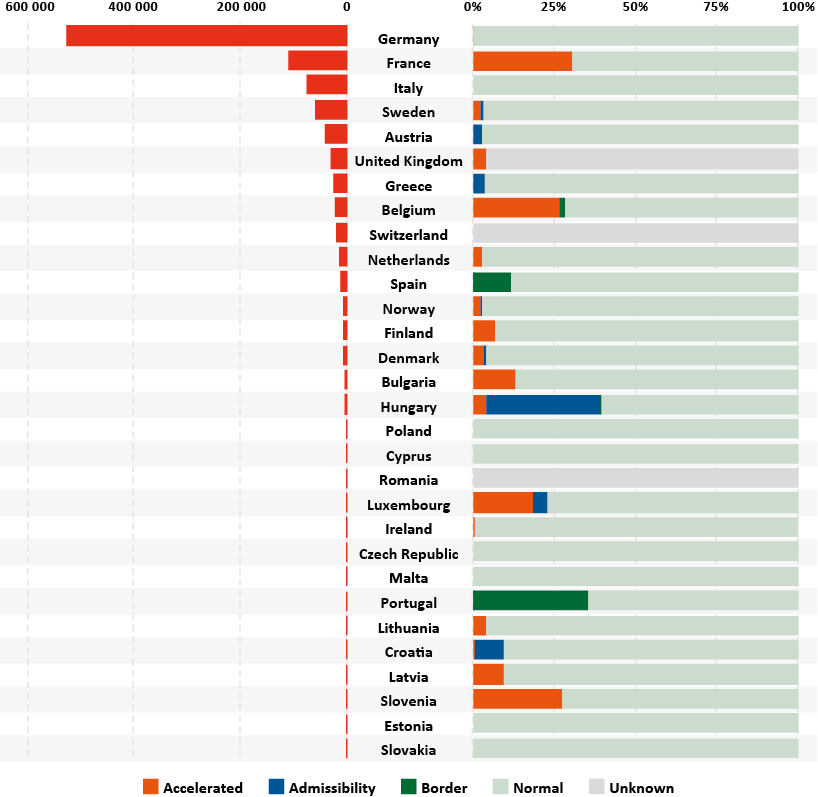

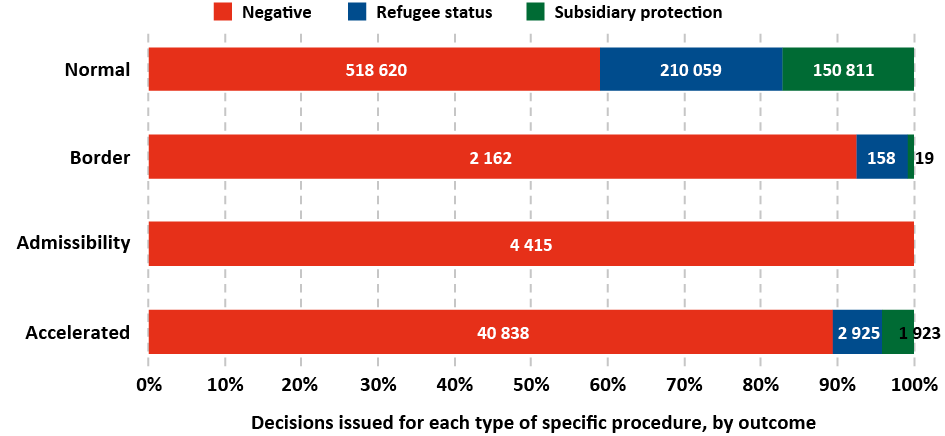

Regarding examination of applications for international protection at first instance, Member States can use special procedures, such as accelerated, border zones, or prioritised procedures, while remaining in accordance with the basic principles and guarantees envisaged in European asylum legislation. EASO data indicates that these procedures are used in a targeted way and as an exception rather than as a rule. Importantly, most decisions issued in the EU+ using accelerated or border procedures lead to a rejection of the application at a significantly higher rate than for decisions made via normal procedures. The recognition rate for decisions issued using accelerated procedures was 11 %, while for those using border procedure it was 8 %. In terms of organisation of their procedures, EU+ countries often resorted to fast-track and prioritised procedures for specific categories of cases, aligned with the workload faced by the specific country. There were also developments in procedures conducted at the border and in transit zones, while many EU+ countries also resorted to the use of safe country concepts, primarily safe country of origin, where several countries amended their national lists of safe countries of origin.

In terms of reception, overall in 2017 decreased pressure was noted on the reception systems of most EU+ countries. Consequently, several administrations reduced their reception capacity by closing various types of reception facilities, combined with progressively replacing emergency or temporary reception centres by more permanent ones, based on previous planning. Against that backdrop, exceptions were noted, as in some other countries the reception capacity was expanded with a view to accommodating an increasing pressure or a demand that was still to be matched. 2017 saw the adoption of new law provisions in a number of Member States regulating the conduct, rights, and duties of asylum seekers while in reception, also pending their removal. In parallel, monitoring standards were developed and related programmes implemented to ensure appropriate reception conditions. In terms of material reception conditions (food, clothing, housing, and financial allowance), as well as healthcare, access to schooling and access to labour market, the developments in specific countries varied significantly, leading to either reduction or extension of offer. Among concerns raised by civil society organisations, the most frequent referred to the lack of reception capacity, poor reception conditions, and/or issues related to the reception of unaccompanied minors.

Similar to reception, in the area of detention diverse developments were noted in individual countries. Overall, a number of EU+ countries revised their legal framework regarding grounds for detention and its implementation in practice. Many countries introduced or planned to introduce new forms of alternatives to detention, in the context of both asylum and return procedures. Concerns about the duration and conditions of detention, and the detention of vulnerable groups, were expressed by UNHCR and civil society in a number of EU+ countries. On a related note, in various EU+ countries new legal provisions entered into force in the course of 2017 limiting the freedom of movement or restricting the residence of people staying in reception. Overall, those developments led to a significant volume of national case law on matters related to freedom of movement and application of detention in various stages of the asylum process.

In 2017, there were 996 685 decisions issued at first instance in EU+ countries. At the national level, similar to 2016, Germany was the country issuing the most decisions (524 185), accounting for 53 % of all decisions in the EU+. Other countries that issued large numbers of decisions included France (11 % of the EU+ total), Italy (8 %), Sweden and Austria (6 % each).

Compared to 2016, fewer decisions were issued at first instance in the majority of EU+ states. The most sizable decreases took place in Germany (a drop by 106 900) and Sweden (a drop by 34 705). In relative terms, among the countries with more than 1 000 decisions at first instance in 2017, the most substantial declines in decisions concerned Finland and Norway (by 65 % each). In contrast, markedly more decisions than in 2016 were issued in France (an increase by close to 24 000), Austria (13 870 more) and in Greece, where the number of decisions increased by 13 055. With respect to decisions issued at first instance, for countries that issued at least 1 000 decisions in 2017, Switzerland had the highest overall recognition rate; 90 % of the decisions were positive. Relatively high recognition rates were also apparent in Norway (71 %), Malta (68 %) and Luxembourg (66 %). Conversely, the Czech Republic had the lowest recognition rate at 12 %, followed by Poland (25 %), France (29 %), Hungary, and the United Kingdom (31 % each).

Differences in recognition rates between countries are the result of the citizenship of the applicants to whom decisions are issued. For example, in 2017 France had a 29 % recognition rate and issued most decisions to Albanian citizens, a nationality with a generally very low recognition rate. In contrast Switzerland, with a 90 % overall recognition rate, issued more than a third of its decisions to Eritreans, a nationality with a considerably high level of positive decisions in the EU+.

Main developments in EU+ countries with regard to procedures at first instance mostly concerned measures taken toward the optimisation of processing of applications for international protection, as well as the reduction of processing times.

In 2017, the EU+ recognition rate of cases decided at second or higher instance was 35 %, considerably higher than in 2016 (17 %). Compared to first instance, the recognition rate is expected to be lower in appeal or review because these cases are examined subsequent to a negative first-instance decision. Indeed, the higher instance recognition rate was 11 percentage points lower than for decisions issued at first instance, but this was a much smaller difference than in 2016, which suggests that in 2017 a higher percentage of negative first instance decisions were overturned in appeal. Among the EU+ countries issuing at least 1 000 second instance decisions, more than half of all higher instance decisions were positive in Finland (65 %), in the Netherlands (58 %), in the United Kingdom (57 %) and in Austria (56 %).

In 2017, developments in EU+ countries concentrated on measures to enhance institutional efficiency, accelerate procedures in second instance with a view to address the high numbers of appeals, and revise procedural rules (mainly in terms of revising the time limits to submit an appeal). With a view to further improve appeal procedures, EU+ countries also implement structural institutional changes.

In 2017, it was also noted that EU+ countries decentralised the procedures on second instance with a view to further enhancing the processing of appeals. Similar to first instance, measures were taken to tackle backlog of pending cases, streamline procedures and make use of technology to support efficient decision-making.

The provision of country of origin information (COI) on a wide range of third countries and themes continues to be vital for well-informed, fair and well-reasoned asylum decisions and evidence-based policy development. While at EU+ level, fewer asylum applications were lodged in 2017 compared to 2016, applications considerably increased in a number of EU+ countries, and overall the applications lodged were distributed among a wider number of nationalities, resulting in a continued need for relevant country of origin information.

In terms of COI production, in addition to a wide range of regular publications by long-established COI Units, many of which are available through the EASO COI Portal, some countries reported their new, if not first ever, outputs in 2017. Overall, EU+ countries further enhanced standards and quality assurance of COI products in the course of 2017, while as a general trend, many national COI Units engaged in a form or collaboration with their counterparts in other countries, including in the framework of EASO COI Networks.

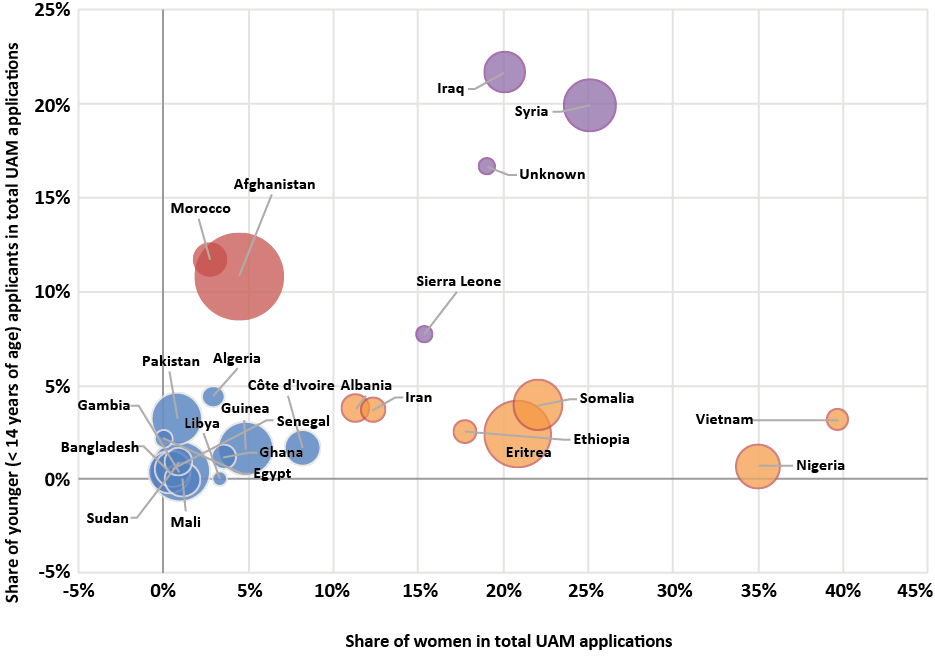

The EU asylum acquis includes rules on the identification of and provision of support to applicants, who are in need of special procedural guarantees (in particular as a result of torture, rape, or any other form of psychological, physical, or sexual violence). One of the key groups is unaccompanied minors seeking protection without care of a responsible adult.

In 2017, approximately 32 715 unaccompanied minors (UAM) applied for international protection in the EU+, half as many as in 2016, with the share of UAMs relative to all applicants being at 4 %. More than three quarters of all UAMs applied in five EU+ countries: Italy, Germany, Greece, the United Kingdom, and Sweden.

The presence of unaccompanied minors drove a number of developments in EU+ countries. Those included, in particular, establishment and enhancing of specialised reception and alternative care modalities, revision of rules for appointment of guardians, and procedural arrangements related to the assessment and securing of the best interest of the child. Similarly, specialised reception facilities and services were at the core of developments concerning other vulnerable groups with many countries creating specialised facilities, as well as mechanisms for identification and referral. Civil society emphasised that efforts are still needed so that support provided is comprehensive, in line with established standards, and ensures early identification of vulnerability in practice.

Persons, who have been granted a form of international protection in an EU+ country, can benefit from a range of rights and benefits linked to this status. Specific rights granted to beneficiaries of international protection are usually laid down in national legislation and policies, often as part of larger-scale integration plans concerning multiple categories of third country nationals, and embedded in national migration policies, where such have been defined at national level. Many countries have adopted national integrations plans and strategies at national level, while others amended existing instruments, often introducing integration courses and mechanisms of integration in the labour market. This fosters the prospects of beneficiaries of protection in gaining their own means of support, while at times access to financial allowances was reduced.

Return policies and measures gained major significance in the course of 2017 among the EU+ countries. Although those relate to the general migration context, in light of increasing numbers of rejected applicants and prospective returnees, various countries adopted new legal provisions in order to facilitate return procedures. Besides the usual support provided in the form of Assisted Voluntary Return, which was also boosted, adopted measures addressed, among others, the enforcement of return decisions and regulated the period prior to departure.

In the course of 2017 most EU+ countries promoted Assisted Voluntary Return initiatives, in various forms: financially, through information campaign, engaging directly in return activities, providing support to other actors, such as IOM or civil society organisations.

1. MAJOR DEVELOPMENTS IN 2017 AT EU LEVEL

1.1. Legislative developments at EU level

1.1.1. Reform of the Common European Asylum System

On 6 April 2016, in its Communication Towards a reform of the Common European Asylum System and enhancing legal avenues to Europe (3 COM(2016) 197 final https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/what-we-do/policies/european-agenda-migration/proposal-implementation-package/docs/20160406/towards_a_reform_of_the_common_european_asylum_system_and_enhancing_legal_avenues_to_europe_-_20160406_en.pdf. ), the Commission laid down five priorities to improve the Common European Asylum System (CEAS). One of these priorities was a strengthened mandate for the European Asylum Support Office (EASO). On 4 May 2016 the Commission presented, as part of a first package of reform of the CEAS, a proposal for a new Regulation (4 COM(2016) 271 final https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/what-we-do/policies/european-agenda-migration/proposal-implementation-package/docs/20160504/easo_proposal_en.pdf. ) that will transform EASO into a fully fledged agency (5 http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?qid=1485250747141&uri=CELEX:52016PC0271. ), as well as proposals for the reform of the Dublin system (6 https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/what-we-do/policies/european-agenda-migration/proposal-implementation-package/docs/20160504/dublin_reform_proposal_en.pdf. ) and for amendments to the Eurodac system (7 http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?qid=1485250294958&uri=CELEX:52016PC0270(01) ).

The intended reform of the Dublin system concentrates on efficient and effective determination of the responsible Member State by removing the clauses on cessation and shift of responsibility and shortening applicable time limits. A corrective allocation mechanism would be introduced to be activated automatically when a Member State receives a disproportionate number of asylum applications. The proposal also envisages stricter obligations for applicants to apply in the first country of entry or Member State of legal residence and remain present there to prevent misuse of the system and secondary movements.

A revision of the Eurodac Regulation was necessary to ensure that the Dublin mechanism continued to have the fingerprint evidence it needed to determine the Member State responsible for examining the asylum application. In addition to this the Commission proposed an extension of the purpose of Eurodac to allow Member States to also monitor secondary movements of irregular migrants who have not sought asylum and to use that information to help facilitate re-documentation and return procedures.

With the proposal to strengthen the mandate of EASO, which will be renamed the European Union Agency for Asylum, the tasks of the Agency will be considerably expanded to address any structural weaknesses that arise in the technical and operational application of the EU’s asylum system. A renewed mandate could include a role in developing the reference key and operating the corrective allocation mechanism under a reformed Dublin System, strengthening the practical cooperation and information exchange between Member States, promoting Union law and operational standards regarding asylum procedures, reception conditions and protection needs, ensuring greater convergence in the assessment of applications for international protection across the Union through the analysis and guidance on the situation in countries of origin, monitoring the application of the CEAS and providing Member States with the necessary operational and technical assistance in particular in situations of disproportionate pressure.

The first package of reform was followed by legislative proposals for a reform of the Asylum Procedures and Qualification Directives as well as the Reception Conditions Directive issued on 13 July 2016 (8 Commission press release http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-16-2433_en.htm. ). Those proposals are aimed at laying down a common procedure for international protection, uniform standards for protection and rights granted to beneficiaries of international protection and the further harmonisation of reception conditions in the EU. The intended reform takes into consideration experiences to date with the CEAS and in particular the requirement for a system able to cater for normal and high migratory pressure in a fully efficient, fair and humane method.

To that end, the Commission proposed to replace the Asylum Procedures and Qualification Directives with Regulations that would be directly applicable in the national asylum systems of Member States, while the Reception Conditions Directive is to be revised.

Under the proposed Asylum Procedure Regulation (9 https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/what-we-do/policies/european-agenda-migration/proposal-implementation-package/docs/20160713/proposal_for_a_common_procedure_for_international_protection_in_the_union_en.pdf. ), the procedure for international protection would be carried out in a more streamlined way and along shorter deadlines, and with strengthened procedural guarantees for applicants (free legal assistance and representation already at the administrative stage of the procedure). Particular attention is given to applicants in need of special procedural guarantees and in particular unaccompanied minors such as the provision for the swift appointment of a guardian. The best interests of the child continue to be a primary consideration in all procedures applicable to minors. In parallel, the applicant’s duty to cooperate with national asylum authorities would be made clearer with stricter rules to prevent any misuse of the system and secondary movements. The Commission is also proposing to further harmonise the application of safe country concepts, including the designation of safe countries of origin and safe third countries at EU level. The proposed Qualification Regulation (10 https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/what-we-do/policies/european-agenda-migration/proposal-implementation-package/docs/20160713/proposal_on_beneficiaries_of_international_protection_-_subsidiary_protection_eligibility_-_protection_granted_en.pdf. ) would align rights of beneficiaries of international protection granted across individual MS (including a proposal to harmonise the duration of respective residence permits, access to rights and social benefits and allowances and obligatory review of continued need for protection). The proposal includes also mechanisms for enhanced convergence of decisions issued through an obligation to follow common guidance on countries of origin and related internal protection alternatives.

The proposed recast of the Reception Conditions Directive (11 https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/what-we-do/policies/european-agenda-migration/proposal-implementation-package/docs/20160713/proposal_on_standards_for_the_reception_of_applicants_for_international_protection_en.pdf. ) aims to ensure greater consistency in reception conditions across the EU. The proposal refers to the application by Member States of standards and indicators on reception conditions developed by EASO, as well as drafting and update of contingency plans for reception capacity. Measures linked to the possibility of assigning a residence to asylum seekers, limiting reception conditions or replacing financial allowances with those provided in kind are all aimed at discouraging absconding and secondary movement. At the same time, access to the labour market would be provided at an earlier stage to prevent dependency on national social systems, while unaccompanied minors’ provision with guardians would come with stronger guarantees and stricter deadlines.

In addition, a Union Resettlement Framework was proposed (12 https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52016PC0468. ). The above legislative proposals to reform CEAS (13 See also European Commission, Factsheets Compilation 2016-2017: Migration and Borders-State of Play of Main Proposals, p.20. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/compilation-factsheets-2016-2017.pdf. The European Parliament provides an overview of the legislative process of various instruments related to migration policies at: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/legislative-train/theme-towards-a-new-policy-on-migration. ) are at various stages of advancement within the legislative process. The aim is to reach political agreement on four proposals (recast Reception Conditions Directive, Qualification Regulation, Eurodac, Union Resettlement Framework Regulation), consensus on the proposal for a Dublin Regulation, and obtain a mandate for negotiations with the European Parliament on the Asylum Procedures Regulation by the end of June 2018 (14 In his 2017 State of the Union Letter of Intent the Commission president Juncker called upon the EP and the Council to adopt the CEAS proposals by the end of 2018. ).

1.1.2. Continued transposition of recast asylum acquis

Member States continued transposing (15

Recast Directives should have been transposed into national law by the general deadline of 20 July 2015. Denmark is not bound by the Directives. UK has opted out of both recast Directives and thus continues to be bound by the Asylum Procedures Directive (Directive 2005/85/EC) and the Reception Conditions Directive (Directive 2003/9/EC). Ireland opted into the Reception Conditions Directive (Directive 2003/9/EC) and continues to be bound only by the Asylum Procedures Directive (Directive 2005/85/EC).

) the provisions of the recast asylum Directives as extensively presented in EASO’s Annual Report on the Situation of Asylum in 2015 (16

EASO, Annual Report on the Situation of Asylum in 2015, 2017, pp. 56-59.

Available at: https://www.easo.europa.eu/sites/default/files/public/EN_%20Annual%20Report%202015_1.pdf.

) and 2016 (17

EASO, Annual Report on the Situation of Asylum in 2016, 2017, p. 57.

Available at: https://www.easo.europa.eu/sites/default/files/annual-report-2016.pdf.

). In Belgium the Law of 21 November 2017 amended the Belgian Immigration Act (Law on Access to the Territory, Residence, Establishment and Removal of Foreigners (18

Loi modifiant l’article 39/73-1 de la loi du 15 décembre 1980 sur l’accès au territoire, le séjour, l’établissement et l’éloignement des étrangers, C − 2017/13845. Available: http://www.ejustice.just.fgov.be/eli/loi/1980/12/15/1980121550/justel.

) and finalised the transposition of the the recast APD and RCD (19

The Belgian Immigration Act was already largely in compliance with the recast of the APD en RCD, but the Law of 21 November 2017 (adopted in the Parliament on 9 Nov. 2017) finalised this transposition. The Law was published in the Belgian Official Gazette on 12 March 2018 to come into force ten days later on 22 March 2018.

). Greece continues working on the implementation of the recast Reception Conditions Directive.

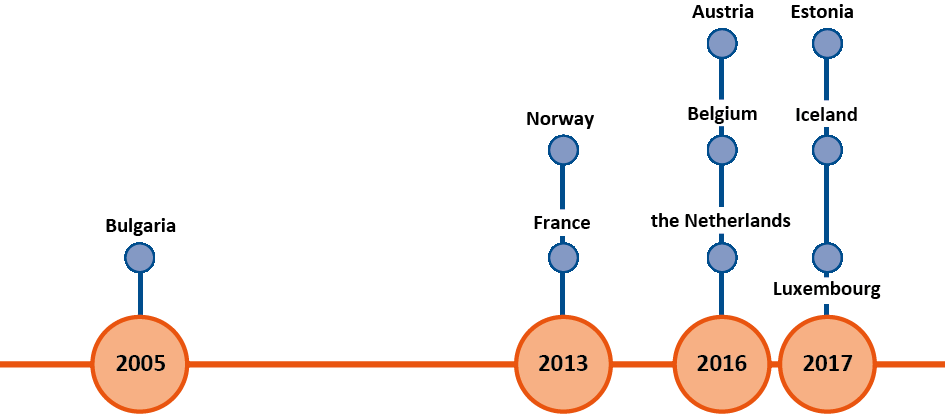

On 21 November 2017, Ireland announced that it will opt into the EU (recast) Reception Conditions Directive (2013/33/EU) (20 Department of Justice and Equality, Press Release, 21 November 2017, available at: http://www.justice.ie/en/JELR/Pages/PR17000394 ).

1.1.3. Infringement procedures by the European Commission

Under the EU Treaties, the European Commission is responsible for ensuring that EU law is correctly applied. As the guardian of the Treaties, the Commission may commence infringement proceedings under Article 258 (ex Article 226 TEC) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union if it considers that a Member State has breached Union law. The purpose of the procedure is to bring the infringement to an end. The infringement procedure starts with a letter of formal notice, by which the Commission allows the Member State to present its views regarding the breach observed. If no reply to the letter of formal notice is received, or if the observations presented by the Member State in reply to that notice cannot be considered satisfactory, the Commission may move to the next stage of the infringement procedure, which is the reasoned opinion; if the Member State does not comply with the opinion the Commission may then refer the case to the Court of Justice (21 https://ec.europa.eu/transport/media/media-corner/infringements-proceedings_en. ).

Infringement procedure against Hungary regarding asylum law

In May 2017, the European Commission decided to move forward on the infringement procedure against Hungary concerning its asylum legislation by sending a complementary letter of formal notice. According the EC Fact Sheet on May infringements (22 European Commission, Fact Sheet May infringements package – Part 1: key decisions, Brussels, 17 May 2017. Available at: http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-17-1280_en.htm. ), following a series of exchanges both at political and technical level with the Hungarian authorities, the letter set out concerns raised by the amendments to the Hungarian asylum law introduced in March 2017 and came as a follow-up to an infringement procedure initiated by the Commission in December 2015. The Commission considered that of the five issues identified in the letter of formal notice from 2015, three remained to be addressed, in particular in the area of asylum procedure. In addition, the letter outlined new incompatibilities of the Hungarian asylum law, as modified by the amendments of 2017. The incompatibilities focused mainly on three areas: asylum procedures, rules on return and reception conditions. The Commission considered that the Hungarian legislation does not comply with EU law, in particular the Asylum Procedures Directive, the Return Directive, the Reception Conditions Directive and several provisions of the Charter of Fundamental Rights.

In December, the European Commission decided to send a reasoned opinion. Following the analysis of the reply provided by the Hungarian authorities on the Commission’s complementary letter of formal notice on 17 May 2017, which was considered unsatisfactory as it failed to address the majority of the concerns and in view of the new legislation adopted by the Hungarian Parliament in October, the Commission considered that the Hungarian legislation does not comply with EU law, in particular Directive 2013/32/EU on Asylum Procedures, Directive 2008/115/EC on Return, Directive 2013/33/EU on Reception Conditions and several provisions of the Charter of Fundamental Rights (23 European Commission, Press release: Migration: Commission steps up infringement against Hungary concerning its asylum law, Brussels, 7 December 2017. Available at: http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-17-5023_en.htm. ). Hungary has responded in February, now it is up to the European Commission to decide whether it turns to the European Court of Justice.

Infringement procedure against the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland regarding relocation

The temporary emergency relocation scheme was established in two Council Decisions in September 2015 (Council Decision (EU) 2015/1523 and Council Decision (EU) 2015/1601), in which Member States committed to relocate persons in need of international protection from Italy and Greece. The Commission has been reporting regularly on the implementation of the two Council Decisions through its regular relocation and resettlement reports, which it has used to call for the necessary action to be taken (24 As of November 2017, the reporting on the relocation and resettlement schemes is included in a consolidated report on the progress made under the European Agenda for Migration. ).

In its 13th report on relocation and resettlement (25 Report from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council and the Council, Thirteenth report on relocation and resettlement, Strasbourg, 13.06.2017, COM(2017) 330 final. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/what-we-do/policies/european-agenda-migration/20170613_thirteenth_report_on_relocation_and_resettlement_en.pdf. ), the European Commission noted that despite repeated calls for action, the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland remained in breach of their legal obligations stemming from the Council Decisions and have shown disregard for their commitments to Greece, Italy and other Member States (26 European Commission, Fact Sheet: June infringements package: key decisions, Brussels, 14 June 2017. Available at: http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-17-1577_en.htm. ). More specifically, despite the Council Decisions requiring Member States to pledge available places for relocation at least every three months to ensure a swift and orderly relocation procedure, Hungary had not pledged or relocated anybody since the relocation scheme started, Poland had not relocated anybody and had not pledged since December 2015, whereas the Czech Republic had only relocated 12 persons and had not pledged or relocated since August 2016. The Commission had previously called in its 12th Relocation and Resettlement report presented on 16 May all Member States that had not relocated or pledged for almost a year or longer in breach of their legal obligations, to start proceedings immediately and within a month.

Consequently, in June 2017, the Commission launched infringement procedures against the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland on non-compliance with their obligations under the 2015 Council Decisions on relocation and addressed letters of formal notice to these three Member States (27 European Commission, Press release: Relocation: Commission launches infringement procedures against the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland, Brussels, 14 June 2017. Available at: http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-17-1607_en.htm. ). On 26 July 2017, the Commission considered the replies provided by the three Member States not satisfactory and decided to move to the next stage of the infringement procedure by sending reasoned opinions (28 European Commission, Press release: Relocation: Commission moves to next stage in infringement procedures against the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland, Brussels, 26 July 2017. Available at: http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-17-2103_en.htm. ). The replies received were found to be not satisfactory and three countries gave no indication on the potential implementation of the relocation decisions. Moreover, the validity of the relocation scheme was confirmed by the Court of Justice of the EU in its ruling on 6 September. Consequently, the Commission decided on 7 December 2017 to refer the three Member States to the Court of Justice of the EU (29 European Commission, Press release: Relocation: Commission refers the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland to the Court of Justice, Brussels, 7 December 2017. Available at: http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-17-5002_en.htm. ).

Infringement procedure against Croatia

The Commission decided to send a reasoned opinion to Croatia requesting that it correctly implement the Eurodac Regulation (Regulation (EU) No 603/2013) (30 European Commission - Fact Sheet, June infringements package: key decisions, Brussels, 14 June 2017. Available at: http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-17-1577_EN.htm. ). The Eurodac Regulation provided for the effective fingerprinting of asylum seekers and irregular migrants apprehended having crossed an external border and the transmission of this data to the central Eurodac database. The Commission sent a letter of formal notice to the Croatian authorities in December 2015 for failing to fully implement the Eurodac regulation. The Commission’s concerns were not addressed, which is why the Commission has followed up with a reasoned opinion. Croatia’s reply announced practical and technical efforts geared towards achieving compliance with the Eurodac Regulation. Eurodac figures and the latest figures received from Frontex as well data provided by the Croatian authorities indicate that progress is being made.

1.2. Jurisprudence of the Court of Justice of the EU

The Court of Justice of the European Union as the guardian of EU Law ensures that, in the interpretation and application of the Treaties, the law is observed (31 Article 19 TEU, Articles 251 to 281 TFEU, Article 136 Euratom, and Protocol No 3 annexed to the Treaties on the Statute of the Court of Justice of the European Union (hereinafter ‘the Statute’). ). As part of its mission, the Court of Justice of the European Union ensures the correct interpretation and application of primary and secondary Union law in the EU, reviews the legality of acts of the Union institutions and decides whether Member States have fulfilled their obligations under primary and secondary law. The Court of Justice also provides interpretation of Union law when so requested by national courts.

The Court thus constitutes the judicial authority of the European Union, which, in cooperation with the courts and tribunals of the Member States, ensures the uniform application and interpretation of EU law (32 https://curia.europa.eu/jcms/jcms/Jo2_6999/en/. ).

2017 was a particularly active year for the CJEU with regard to asylum law. 16 judgements were issued while another 16 are still pending (33 As of March 2018. ). Out of them, 7 judgements were related to the implementation of the Dublin Regulation, which is indicative of the impact of the mass influx of asylum seekers in 2015-16, the secondary movements thereafter and the particular challenges encountered in this specific area in the light of the European Charter of Fundamental Rights.

Dublin III Regulation

The legality of mass border crossings, tolerated by the authorities of the first Member State faced with an exceptionally large number of third country nationals wishing to transit through that Member State in order to make an application for international protection in another Member State, in the light of Dublin III Regulation, was questioned in Cases C-490/16 (34 Judgment of the Court (Grand Chamber) of 26 July 2017, A.S. v Republic of Slovenia, Case C-490/16, ECLI:EU:C:2017:585. ) and C-646/16 (35 Judgment of the Court (Grand Chamber) of 26 July 2017, Proceedings brought by Khadija Jafari and Zainab Jafari, Case C-646/16, ECLI:EU:C:2017:586. ). The Court observed that the admission of a national from a non-EU country to the territory of a Member State is not tantamount to the issuing of a visa, even if the admission is explained by exceptional circumstances characterised by a mass influx of displaced people into the EU. Moreover, the Court considered that the crossing of a border in breach of the conditions imposed by the rules applicable in the Member State concerned must necessarily be considered ‘irregular’ within the meaning of the Dublin III Regulation. Consequently, the Court found that the term ‘irregular crossing of a border’ also covered the situation in which a Member State admits into its territory non-EU nationals on humanitarian grounds, by way of derogation from the entry conditions generally imposed on non-EU nationals. In addition, referring to the mechanisms established by the Dublin III Regulation, to Directive 2001/553 and to Article 78(3) TFEU, the Court considered that the fact that the border crossing occurred upon the arrival of an unusually large number of non-EU nationals seeking international protection is not decisive. It further observed that the taking charge of such non-EU nationals may be facilitated by the use by other Member States, unilaterally or bilaterally in a spirit of solidarity, of the ‘sovereignty clause’, which enables them to decide to examine applications for international protection lodged with them, even if they are not required to carry out such an examination under the criteria laid down in the Dublin III Regulation. Finally, the Court reiterated that an applicant for international protection should not be transferred to the Member State responsible if, following the arrival of an unusually large number of non-EU nationals seeking international protection, there is a genuine risk that the person concerned may suffer inhuman or degrading treatment if transferred (36 CJEU, Press Release No 86/2017: 26 July 2017. Available at: https://curia.europa.eu/jcms/upload/docs/application/pdf/2017-07/cp170086en.pdf. ).

The rights of asylum seekers in relation to the Dublin III Regulation and the applicable time limits were also under review. In Case C-670/16 (37 Judgment of the Court (Grand Chamber) of 26 July 2017, Tsegezab Mengesteab v Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Case C-670/16, ECLI:EU:C:2017:587. ), which the Court examined under the expedited procedure, it stated that the Dublin III Regulation did not merely introduce organisational rules governing relations between Member States for the purpose of determining the Member State responsible, but decided to involve asylum seekers in that process, by conferring on them, inter alia, the right to an effective remedy in respect of any transfer decision that may be taken against them. To this end, an applicant for international protection may rely, in the context of an action brought against a decision to transfer him, on the expiry of the three-month period at issue, even if the requested Member State is willing to take charge of him. Second, the Court stated that a take-charge request cannot legitimately be made more than three months after the application for international protection has been lodged. The two-month period which the Dublin III Regulation provides for such a request in the event of receipt of a Eurodac hit does not constitute a supplementary period, which is added to the three-month period, but a shorter period which is justified by the fact that such a hit constitutes evidence of illegal crossing of an external frontier of the EU and accordingly simplifies the process of determining the responsible Member State. Third, as regards the substantive definition of the application for international protection (the lodging of which starts the three-month period), the Court hold that: ‘an application for international protection is deemed to have been lodged if a written document, prepared by a public authority and certifying that a non-EU national has requested international protection, has reached the authority responsible for implementing its obligations arising from the Dublin III Regulation, or, as the case may be, if only the main information contained in that document (but not that document itself or its copy) has reached that authority’ (38 CJEU, Press Release No 87/2017: 26 July 2017. Available at: https://curia.europa.eu/jcms/upload/docs/application/pdf/2017-07/cp170087en.pdf. ).

In addition, in the judgement in Case C-201/15 Shiri, the Court affirmed (39 Judgment of the Court (Grand Chamber) of 25 October 2017, Majid auch Madzhdi Shiri v Bundesamt für Fremdenwesen und Asyl, Case C-201/16, ECLI:EU:C:2017:805. ) that an applicant for international protection can rely, before a court or tribunal, on the expiry of the period laid down for his removal to another Member State. In particular, the Court replied that, where the transfer does not take place within the six-month time limit, responsibility is transferred automatically to the Member State which requested that charge be taken of the person concerned (in this instance, Austria), without it being necessary for the Member State responsible (in this instance, Bulgaria) to refuse to take charge of, or take back, that person. Such a solution ensures that, in the event of a delay in the take charge or take back procedure, the examination of the application for international protection will be carried out in the Member State where the applicant is, so as not to delay that examination further. The Court held that an applicant for international protection can rely on the expiry of the six-month period. That is true irrespective of whether that period expired before or after the transfer decision was adopted. The Member States are obliged to provide in this regard for an effective and rapid remedy (40 CJEU, Press Release No 111/2017 : 25 October 2017. Available at: https://curia.europa.eu/jcms/upload/docs/application/pdf/2017-10/cp170111en.pdf. ).

With regard to the transfer-back procedure of seriously ill asylum seekers, the Court interpreted (41 Judgment of the Court (Fifth Chamber) of 16 February 2017, C. K. and Others v Republika Slovenija, Case C-578/16 PPU, ECLI:EU:C:2017:127. ) Articles 3(2) and 17(1) of Dublin III Regulation in relation to Article 267 TFEU and Article 4 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union. The Court held that the application of the ‘discretionary clause’ is not governed solely by national law and by the interpretation given to it by the constitutional court of the Member States, but is a question concerning the interpretation of EU law. The court clarified that even in the absence of substantial grounds for believing that there are systemic flaws in the Member State responsible for examining the application for asylum, the Dublin transfer can take place only in conditions which exclude the possibility that it might result in a real and proven risk of the person concerned suffering inhuman or degrading treatment. In circumstances in which the transfer of an asylum seeker with a particularly serious mental or physical illness would result in a real and proven risk of a significant and permanent deterioration in the state of health of the person concerned, that transfer would constitute inhuman and degrading treatment. In this regard, it is for the authorities of the Member State having to carry out the transfer and, if necessary, its courts to eliminate any serious doubts concerning the impact of the transfer on the state of health of the person concerned by taking the necessary precautions to ensure that the transfer takes place in conditions enabling appropriate and sufficient protection of that person’s state of health. If, taking into account the particular seriousness of the illness of the asylum seeker concerned, the taking of those precautions is not sufficient to ensure that his transfer does not result in a real risk of a significant and permanent worsening of his state of health, it is for the authorities of the Member States concerned to suspend the execution of the transfer of the person concerned for such time as his condition renders him unfit for such a transfer. Where necessary, if it is noted that the state of health of the asylum seeker concerned is not expected to improve in the short term, or that the suspension of the procedure for a long period would risk worsening the condition of the person concerned, the requesting Member State may choose to conduct its own examination of that person’s application by making use of the ‘discretionary clause’ laid down in Article 17(1) of Regulation No 604/2013.

Detention in the context of Dublin III Regulation was also subject of the Court’s activity. Case C-528/15 (42 Judgment of the Court (Second Chamber) of 15 March 2017, Policie ČR, Krajské ředitelství policie Ústeckého kraje, odbor cizinecké policie v Salah Al Chodor and Others, Case C-528/15, ECLI:EU:C:2017:213. ) Al Chodor, concerned the detention of applicants in order to secure transfer procedures when there is a significant risk of absconding. In this regard, to be able to apply detention Member States must establish, in a binding provision of general application, objective criteria underlying the reasons for believing that an applicant for international protection who is subject to a transfer procedure may abscond. The absence of such a provision leads to the inapplicability of Article 28(2) of the Dublin regulation.

Further in Case C-60/16 (43 Judgment of the Court (Third Chamber) of 13 September 2017, Mohammad Khir Amayry v Migrationsverket, Case C-60/16, ECLI:EU:C:2017:675. ), the Court ruled that Article 28 of Dublin Regulation read in conjunction with Article 6 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, does not preclude national legislation, which provides that, where the detention of an applicant for international protection begins after the requested Member State has accepted the take charge request, that detention may be maintained for no longer than two months, provided, first, that the duration of the detention does not go beyond the period of time which is necessary for the purposes of that transfer procedure, assessed by taking account of the specific requirements of that procedure in each specific case and, second, that, where applicable, that duration is not to be longer than six weeks from the date when the appeal or review ceases to have suspensive effect, as well as national legislation, which allows, in such a situation, the detention to be maintained for 3 or 12 months during which the transfer could be reasonably carried out. It also clarified that the number of days during which the person concerned was already detained after a Member State has accepted the take charge or take back request need not be deducted from the six-week period established by that provision, from the moment when the appeal or review no longer has suspensive effect. The six-week period beginning from the moment when the appeal or review no longer has suspensive effect, established by that provision, also applies when the suspension of the execution of the transfer decision was not specifically requested by the person concerned.

The applicability of Dublin III was also questioned with regard to an asylum seeker who had been granted subsidiary protection in the Member State of first entry. More analytically, on 7 December 2015, Mr Ahmed applied for asylum in Germany and lodged an application for international protection with the Office on 30 June 2016. As a search on the Eurodac system showed that the applicant had already applied for international protection in Italy on 17 October 2013, the Office requested the Italian authorities to take him back on the basis of Regulation No 604/2013. The Italian authorities refused the request for a take-back on the grounds that the applicant benefits from subsidiary protection in Italy, so that his transfer there should take place in accordance with the readmission agreements in force. Consequently, the application was rejected as inadmissible, whereas it found there were no grounds preventing his deportation to Italy, informed him that he could be deported to that Member State if he did not leave Germany, and imposed a ban on his entry and residence for 30 months from the date of deportation. The decision was taken before the referring court, which requested a preliminary ruling to clarify if Dublin III Regulation is applicable to asylum applicants to whom subsidiary protection has already been granted in a Member State. The Court in this case ruled that the provisions and principles of Regulation (EU) No 604/2013 which govern, directly or indirectly, the time limits for lodging an application for a take-back are not applicable in a situation such as that at issue in the main proceedings, in which a third country national has lodged an application for international protection in one Member State after being granted the benefit of subsidiary protection by another Member State (44 Order of the Court (Third Chamber) of 5 April 2017, Daher Muse Ahmed v Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Case C-36/17, ECLI:EU:C:2017:273. ).

In early 2018, the Court also determined responsibility of Member States when an applicant, after lodging a second asylum application in another Member State, was transferred to the Member State having original responsibility for the first asylum application because of a court’s rejection of his application for suspension of the transfer decision under the Dublin III Regulation, and then immediately returned illegally to the second Member State, and interpreted relevant procedural aspects in application of Dublin III Regulation (45 Judgment of the Court (Third Chamber) of 25 January 2018, Bundesrepublik Deutschland v Aziz Hasan, Case C-360/16, ECLI:EU:C:2018:35. ).

Among the pending cases (46 As of March 2018, the following cases are pending: C-647/16, C-47/17, C48/17, C-56/17, C-163/17, C-213/17, C-577/17, C-583/17. ), the application of the Dublin III Regulation in relation to Brexit is of special interest, as the Court has been asked whether a national authority when dealing with the transfer of an applicant to the UK should take into account circumstances in relation to the withdrawal of the UK from the EU, as they stand at the time of such consideration (47 Case C-661/17. ).

Asylum Procedures Directive

The issue of the requirement to hold a hearing in the appeal proceedings was considered by the Court upon request for a preliminary ruling from the Tribunale di Milano in Case C-348/16 (48 Judgment of the Court (Second Chamber) of 26 July 2017, Moussa Sacko v Commissione Territoriale per il riconoscimento della Protezione internazionale di Milano, Case C-348/16, ECLI:EU:C:2017:591. ). In this regard, the Court ruled that the national court or tribunal hearing an appeal against a decision rejecting a manifestly unfounded application for international protection is not precluded from dismissing the appeal without hearing the applicant, where the factual circumstances leave no doubt as to whether that decision was well founded and under two conditions: first, during the proceedings at first instance, the applicant was given the opportunity of a personal interview on his or her application for international protection, in accordance with Article 14 of the directive, and the report or transcript of the interview, if an interview was conducted, was placed on the case file, in accordance with Article 17(2) of the directive, and, second, the court hearing the appeal may order that a hearing be conducted if it considers it necessary for the purpose of ensuring that there is a full and ex nunc examination of both facts and points of law.