Country Report

1. Key Indicators

Figure 1: Key indicators overview

| Lithuania | EU | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 2021 | 2011 | 2021 | ||||||

| EU-level-targets | 2030 target | ||||||||

| Participation in early childhood education (from age 3 to starting age of compulsory primary education) | ≥ 96% | 83.4%13 | 90.9%20 | 91.8%13 | 93.0%20 | ||||

| Low achieving eighth-graders in digital skills | < 15% | 45.1%13 | : | : | : | ||||

| Low achieving 15-year-olds in: | Reading | < 15% | 24.4%09 | 24.4%18 | 19.7%09 | 22.5%18 | |||

| Maths | < 15% | 26.3%09 | 25.6%18 | 22.7%09 | 22.9%18 | ||||

| Science | < 15% | 17.0%09 | 22.2%18 | 18.2%09 | 22.3%18 | ||||

| Early leavers from education and training (age 18-24) | < 9% | 7.4% | 5.3%b | 13.2% | 9.7%b | ||||

| Exposure of VET graduates to work-based learning | ≥ 60% (2025) | : | 48.7% | : | 60.7% | ||||

| Tertiary educational attainment (age 25-34) | ≥ 45% | 48.2% | 57.5%b | 33.0% | 41.2% | ||||

| Participation of adults in learning (age 25-64) | ≥ 47% (2025) | : | : | : | : | ||||

| Other contextual indicators | |||||||||

| Equity indicator (percentage points) | : | 20.418 | : | 19.30%18 | |||||

| Early leavers from education and training (age 18-24) | Native | 7.4% | 5.3%b | 11.9% | 8.5%b | ||||

| EU-born | : | :bu | 25.3% | 21.4%b | |||||

| Non EU-born | :u | :bu | 31.4% | 21.6%b | |||||

| Upper secondary level attainment (age 20-24, ISCED 3-8) | 87.7% | 91.9%b | 79.6% | 84.6%b | |||||

| Tertiary educational attainment (age 25-34) | Native | 48.2% | 57.5%b | 34.3% | 42.1%b | ||||

| EU-born | :u | :bu | 28.8% | 40.7%b | |||||

| Non EU-born | :u | 59.9%bu | 23.4% | 34.7%b | |||||

| Education investment | Public expenditure on education as a percentage of GDP | 5.6% | 5.2%20 | 4.9% | 5.0%20 | ||||

| Public expenditure on education as a share of the total general government expenditure | 13.1% | 12.0%20 | 10.0% | 9.4%20 | |||||

Sources: Eurostat (UOE, LFS, COFOG); OECD (PISA). Further information can be found in Annex I and at Monitor Toolbox. Notes: The 2018 EU average on PISA reading performance does not include ES; the indicator used (ECE) refers to early-childhood education and care programmes which are considered by the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) to be ‘educational’ and therefore constitute the first level of education in education and training systems – ISCED level 0; the equity indicator shows the gap in the share of underachievement in reading, mathematics and science (combined) among 15-year-olds between the lowest and highest quarters of socio-economic status; b = break in time series, u = low reliability, : = not available, 09 = 2009, 13 = 2013, 18 = 2018, 20 = 2020.

Figure 2: Position in relation to strongest and weakest performers

2. A focus on equity in education

Lithuania’s education system is marked by an urban-rural divide. Participation in early childhood education tends to be lower in rural areas, and student outcomes are marked by a significant urban-rural gap (European Commission, 2020). The early school leaving rate is almost four times higher in rural areas (8.2% in 2021) than in urban areas (2.2%1) and the tertiary attainment rate for people aged 25-34 is much lower (43.6% vs 70.6% in 2021). A significant urban-rural gap also exists in the level of digital skills2. This partly reflects broader socio-economic disparities, which are stronger in Lithuania than on EU average, and have been increasing over the past two decades3. The positive effects of Lithuania’s rapid economic convergence are mainly felt by the two largest cities – Vilnius and Kaunas – while other towns and municipalities do not attract enough investment. Only four out of 60 municipalities have registered population growth over the past decade, namely the two largest cities and the resorts along the Baltic coast (OECD, 2020b). A lack of access to quality social services, including education, makes rural areas less attractive and widens the rural-urban divide. It increases migration to bigger cities, creating a risk of overpopulation there. In schools in Vilnius, Kaunas and Klaipeda, pupils are enrolled in overcrowded classes4, and demand for early childhood education and care (ECEC) is not fully met (European Commission, 2020).

Socio-economic factors play a key role in educational disparities. Students in rural areas perform worse than those in urban areas in the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), but would actually outperform them if they had the same socio-economic profile (Echazarra, A., and Radinger, T., 2019). The Lithuanian school system can currently not compensate for the socio-economic disparities at individual, school and municipal level. Schools enjoy great autonomy. In combination with school accountability, it can help improve student achievement European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2020). Insufficient accountability bears the risk of differences in the quality of education provision and, consequently, negatively affects equity. In Lithuania, the use of academic performance criteria for school admissions at lower secondary level is not compulsory, but school heads report using academic performance in practice5. Unequal approaches to setting school and programme admission criteria can exacerbate differences between schools and increase segregation (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2020). The 2018 PISA report shows that Lithuanian disadvantaged pupils are more likely to be concentrated in the same schools (OECD, 2019c). Student performance is closely related to socio-economic background in Lithuania (European Commission, 2020); admissions based on academic performance risk perpetuating the stratification of students not only by ability, but also by socio-economic background. Grouping pupils by ability is a common practice in lower secondary schools that risks increasing the performance gap between students from disadvantaged and more affluent backgrounds. Overcrowding of public schools in the bigger cities due to internal migration also plays a role in the dramatic expansion of the number of students enrolled in private schools, which increased by 49.2% between 2015 and 2020 (EU: 4.7%). The share of primary and secondary school students (ISCED 1-3) attending private schools is relatively low as it stood at 4.4% in 2020, but according to the 2018 PISA report, students in private schools perform better than those in public schools (European Commission, 2020).

Socio-economic differences also impact access to tertiary education. State-funded study places are allocated based on the results of school leaving exams. This merit-based approach does not effectively support the participation of students from vulnerable groups in higher education, especially in universities, as they often cannot compete with their peers’ academic achievements. In 2020, only 17% of upper secondary students from low-income families entered tertiary education, compared to 68% from high-income families (OECD, 2021). Students from vulnerable groups who cannot receive public funding are more likely to abandon their plans to pursue university education, and opt for colleges or other alternatives. Study loans are unattractive for many (STRATA, 2020a).

3. Early childhood education and care

Participation in early childhood education keeps increasing. In 2020, 90.9% of 3-6-year-olds participated in early childhood education, below the EU average of 93% (Figure 3). The rate has increased by 3.4 pps since 2015 and further increases are expected due to the planned measures to increase access and participation (European Commission, 2021). Participation in formal childcare before the age of 3 dropped by 10.4 pps between 2019 and 2020, standing at 16.2%6, below the EU average of 32.4%7. This disruption was probably due to the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Planned investment may help Lithuania to better ensure equal enrolment in early childhood education and care (ECEC) across the country. Increasing access to ECEC requires: (i) tackling provision imbalances in Lithuania (European Commission, 2020); (ii) increasing the number of teachers; and (iii) improving their working conditions. For 2021-2027, Lithuania has planned further investment in kindergartens from national budget and EU funds. This investment will address infrastructure gaps identified by the Ministry of Education, Science and Sport in the first half of 2022, as envisaged in the national recovery and resilience plan. The arrival of Ukrainian displaced children has exacerbated the problem of limited ECEC provision in urban areas. To react quickly to the higher demand for places, the government has further increased the number of children in preschool and pre-primary groups, and the salaries of teachers working in these bigger groups depending on the number of Ukrainian children. These changes are valid until August 2023.

Measures to improve the quality of ECEC are underway. A methodology for self- and external evaluation of the quality of pre-primary and preschool institutions was piloted in 2021. This was the first step in developing a more comprehensive quality monitoring system (European Commission, 2021; OECD, 2017). The assessed areas were: (i) child welfare; (ii) educational content and environment; (iii) educational strategies; (iv) assessment of achievements; and (v) cooperation with children’s families. The results of the pilot showed that external evaluations provide the opportunity to assess the quality of the service provided and the effectiveness of pedagogical practices. In 2022 the Minister of Education, Science and Sport approved the guidelines for the organization and implementation of the external quality assessment for schools implementing preschool and/or preprimary curricula. By the order of the Minister of Education, Science and Sport an updated pre-primary education curriculum has been approved and will be implemented as of September 20238. Pre-school guidelines have to prepared until the same date. ECEC staff will be encouraged to adapt the educational content and their teaching practices to children’s learning needs. Providing ECEC staff and school leaders with professional development opportunities will be key to making these changes effective.

Figure 3: Participation in early childhood education of pupils from age 3 to the starting age of compulsory primary education, 2015 and 2020 (%)

4. School education

School curricula and the student assessment system are being reformed. In 2018, Lithuania started to work on a new competence-based curriculum to improve student learning outcomes, which are slightly below the EU average (European Commission, 2020, and Figure 1). The new curriculum is planned to be implemented from the 2023/2024 school year at primary and secondary level. Preparatory work has involved training teachers and school leaders, as they are key stakeholders of the implementation process. The reform will be accompanied by changes in the assessment system, which is currently focused on subject matter knowledge rather than cross cutting skills (OECD, 2022). It is proposed to introduce intermediate tests on pupils’ achievements in the last two grades, whose results will be included in the final school leaving mark. The objective is to provide stronger incentives for students to invest earlier and more comprehensively in the secondary curriculum instead of focusing disproportionately on the two subjects of the final exam (OECD, 2013). Intensive teacher training is being organised to support student assessment. Strengthening the use of assessment results by teachers and school leaders and in regular school monitoring and evaluation could help achieve better student outcomes and a more effective use of school resources. Although municipalities have been encouraged to report on school quality and progress since 2013, only 4 out of 60 municipalities published annual reports between 2017 and 2020 (Ministry of Education, Science and Sport, 2021b).

Box 1: Supporting school principals as leaders as part of the curriculum reform in Lithuania

With the support of the EU’s Structural Reform Support Programme, Lithuania has worked to increase school principals’ ability to play a pivotal role in improving teaching quality in their schools as part of the ongoing reform. The shift to a competence-based curriculum will require changes in teaching practices, for instance, 30% of the curriculum will be at the discretion of teachers, to achieve more enquiry-based learning and support from school leaders and structures of leadership in schools. School principals will have to encourage teachers to take part in specific, and school-based professional development activities on the new curriculum. The project provided Lithuania with recommendations for the curriculum reform to bring about the desired changes, including: (i) identifying future training and development needs of school leaders, teachers and municipal decision-makers; (ii) investing in specific formats of professional development, such as school-based coaching, upskilling on digital education, and a Master level qualification on school and curriculum leadership (iii) further aligning policies on school leadership and teachers’ career progression with the curriculum reform.

More information available at: https://www.britishcouncil.lt/programmes/supporting-school-principals-leaders-curriculum-reform-lithuania

Steps are being taken to address teaching shortages. The ageing of the teaching workforce and the low number of education graduates entering the profession are among the factors causing the low supply of teachers (European Commission, 2019). At the same time, planned measures such as introducing universal preschool education, extending the duration of pre-primary education, and developing inclusive education (European Commission, 2021) will increase the demand for teachers. This is being addressed by offering scholarships to students in their final year who sign a 3-year employment contract with a school or a municipality, and to those studying psychology. In addition, the government is planning to expand funding and opportunities for in-service teachers to obtain an additional specialisation to teach a second subject. In 2021, the Ministry of Education, Science and Sport also made the qualification requirements for teachers more flexible to allow motivated professionals who do not have a teacher qualification to work as a teacher.

Improving working conditions may help increase the low perception of the teaching profession. To do so, Lithuania is considering reviewing the career model. At present, teachers can voluntarily apply to get into one of the higher qualification categories, namely senior teacher, teacher-methodologist and teacher-expert, enabling them to take up higher responsibilities and receive higher salaries. However, financial incentives are limited, and functions do not vary among the various levels. In recent years, teacher remuneration has been increased, which can also help attract new teachers and make the profession more attractive. The reorganisation of the school network (European Commission, 2021) may also have a positive impact on teacher workload and salaries. A teacher’s salary depends also on the number of lessons taught, which implies that teachers working in small municipalities with a low number of classes tend to have fewer hours and need to travel more to get a higher salary (Ministry of Education, Science and Sport, 2021b). The school reorganisation may help address this issue by reducing the number of small schools. To make the profession more attractive, the relevance and fragmentation of continuous professional development system is yet to be improved to be better adapted to the teachers’ and students’ needs (Ministry of Education, Science and Sport, 2021a) and to the latest knowledge of educational sciences. Between 2021 and 2027, Lithuania plans to invest resources from the European Structural and Investment Funds to improve quality of education studies by strengthening education research and increasing enrolment in doctoral studies in education.

Addressing education inequalities at school level is a key priority. Addressing regional disparities, including those in access to quality education, is at the core of investment planned for 2021-2027 with EU funds including the RRF. Investment is planned for the purchase of science laboratories and tools and for the further development of the current all-day school programme9. In Lithuania, all-day schools are settings in which children are provided with educational activities after official school hours to improve the inclusion of children from vulnerable backgrounds. The Millennium School programme envisaged in the recovery and resilience plan (European Commission, 2021) may help to provide equal opportunities for all children irrespective of their living place and to improve overall academic achievements. The programme promotes networking between municipalities and schools that choose to apply for it. All children from the surrounding region will be able to use the facilities and courses provided at these schools. The schools admitted to the programme cannot select students and must present a 5-year programme to increase school quality and inclusiveness. Monitoring the implementation of the programme and steering the process at central level are key to ensuring that all municipalities are benefiting from the programme.

Lithuania is investing in the integration of special needs students into mainstream schools. As of 2024, all schools must ensure access for children with special needs and provide them with the necessary assistance (European Commission, 2021). In 2021, the National Education Agency carried out the first external evaluation of inclusive education in 30 schools to improve the design of measures for effective inclusive education in mainstream schools. One of the findings of the evaluation is that teaching practices are not adapted10. The Millennium School programme will help achieve this objective by providing funding to improve the physical environment of schools in line with the principles of universal design, and by strengthening teachers’ skills in working with pupils with special needs. In 2021-2027, Lithuania plans to strengthen the provision of educational assistance by setting up regional advisory centres. The purpose is to provide schools and parents with guidance to better assess the educational needs and to adapt didactics in the whole territory.

Box 2: Preparing schools for inclusive education

The European Social Fund project ‘Smart and Learning Children of Kaunas district’ aims to increase the inclusion of pupils with special educational needs into mainstream schools in Kaunas.

The 2020-2022 project develops and pilots an innovative model for providing education, social and health services to children of all ages. To support children, a multidisciplinary team is available, but also workshops, stress management seminars, art and music therapy sessions. The project also aims to develop an interactive platform to provide support and guidance material to professionals and parents.

5. Vocational education and training and adult learning

Reforms in the area of vocational education and training (VET) envisaged in the recovery and resilience plan are expected to bring improvements. Lithuania has completed the launch of the National Platform on Progress in Vocational Education and Training, encompassing social partners, the educational community and public authorities. The platform advises the Ministry of Education, Science and Sport on the consolidation of the VET network. By September 2022, the Ministry has optimised at least 20% of the current VET network. In 2022, the number of VET institutions was reduced from 56 to 44. The platform will also advise the Ministry on various other issues, such as updates of the VET curriculum and professional standards (at least 95 new or updated VET programmes by 2026), training of VET trainers, and professional development (at least 1 000 trainers by 2026).

Lithuania continues to develop a new career guidance model. Career guidance will be compulsory for all students from the first to the final grade in all schools including vocational education schools, and will be provided by career specialists, who will work based on a standardised programme. The Ministry adopted the qualification requirements for career specialists, and works on the development of the necessary training. The aim was that career specialists who meet new qualification started working in schools from 1 September 2022; however, the transition period for current specialists not meeting the qualification requirements may take longer.

Measures are underway to improve the quality and the attractiveness of vocational education. Compared to the EU average, enrolment in VET is fairly low (24.7% of upper secondary pupils in 2020, compared to an EU average of 48.7%). Recent VET graduates’ employment rate (69.8% in 2021) is also below the EU average (76.4%). In 2021, Lithuania started external monitoring of VET institutions using the new quality monitoring system. In the 2020-2021 school year, an external evaluation of 12 vocational education institutions was carried out with European Social Fund support, 8 more institutions will be evaluated in 2022. In January 2022, renewed rules on assessment of acquired VET skills entered into force. They provide for an electronic assessment of theoretical knowledge, whereas the assessment of practical skills will take place in sectoral practical training centres. .

Lithuania continues to work on delivering the main reform in the area of adult learning. As defined in the RRP, the legislative proposal for a one-stop-shop lifelong learning model, accompanied by an IT system based on individual learning accounts, is being prepared to be submitted to the Parliament. The harmonised description of the IT system and its functionalities is being finalised. The IT system will facilitate the collection of all adult education offers that correspond to the established quality criteria. This will help learners to find courses, and education providers to offer courses. The system of individual learning accounts will help to fund courses for various social groups of learners. This is expected to increase the level of participation in adult education. Lithuania aims to have 21 600 people (aged 18-65) who have completed quality assured training (at least 40% of which dedicated to digital skills) in the lifelong learning framework by 2026. In relation to the 2030 target for adult learning participation in 1 year, Lithuania has committed to achieve 53.7% by 2030, more than doubling the 25% rate of 2016.

Lithuania developed a learning support scheme, as envisaged in the recovery and resilience plan. The scheme will support both unemployed and employed who seek to obtain high value-added qualifications and skills. According to the recovery and resilience plan, 19 350 participants will obtain skills and qualifications in high value-added areas (10 000 of them in digital skills).

6. Higher education

A high proportion of young people in Lithuania have attained tertiary education. In 2021, tertiary attainment among those aged 25-34 was 57.5%, among the highest of all EU countries and well above the EU average (41.2%). A relatively high proportion of tertiary educated young adults in Lithuania have a bachelor’s degree as their highest qualification, in part because many graduate from colleges, which offer 3-year vocationally oriented bachelor’s degrees (OECD, 2017). However, the high tertiary education rate is also the result of high emigration of lower-educated young people, which masks declining enrolments in tertiary education since 2011 in line with population decline (OECD, 2021). Gender differences in tertiary attainment rate are among the highest in the EU, with women (67.9% vs 46.8% at EU level) being much more likely to hold a tertiary degree than men (48.4% vs 35.7% at EU level) (Figure 4). However, over the total ICT graduates the share of women was lower than the EU average in 2020 (17.8% vs 20.8%).

Figure 4: Tertiary attainment rate (25-34) by sex, 2021

Introducing multiple pathways to higher education and strengthening career guidance may help improve equity in access to higher education. Besides academic and financial barriers (see Section 2), also a lack of information may play a role in making academic choices: students from low socio-economic backgrounds feel less informed about the conditions for joining universities compared to high socio-economic background students. Career guidance services are often not available to the same standard throughout Lithuania (OECD, 2021), and career planning specialists are not yet skilled enough to advise on further studies or future career choices (STRATA, 2020b). Advantaged schools are more able to provide better guidance (OECD, 2019). Effective counselling in all upper secondary schools could help choose between post-secondary VET, professionally oriented colleges or universities. Between 2015 and 2020, the number of state-funded places was increased, with limited impact on equity (STRATA, 2020a)11. As of 2024, up to 10% of state-funded places will support access of vulnerable students. On the contrary, policy measures to increase enrolments of disadvantaged students could target fields experiencing skills shortages or/and of strategic importance to also improve higher education’s responsiveness to labour market needs. As of September 2022, colleges provide short-cycle tertiary studies in the fields of computer engineering, systems programming and tourism, which is a good step in this direction. It may provide an attractive pathway to higher education for students from low socio-economic backgrounds and for VET secondary graduates who tend to be more attracted by vocational and/or short studies than their peers from high socio-economic backgrounds. Making the provision of career guidance mandatory (see above) may be a way of promoting social mobility and making more informed decisions also taking into account labour market trends.

Ongoing reforms pave the way for quality improvements. Academic excellence and labour market relevance of tertiary institutions are relatively low (OECD, 2022). With around 40 institutions, the network of tertiary education is scattered, featuring much overlap and duplication across institutions and lacking critical mass to reach excellence. The alignment of admission requirements for state-funded and non-state funded tertiary education institutions (which used to be lower for non-state-funded institutions) is to come into effect in 2024. This, together with the measures envisaged for the school leaving exam, which aim to raise the achievements of tertiary students (see Section 4), may help improve the situation (European Commission, 2020; STRATA 2020a). Lithuania is using funding arrangements in favour of quality and efficiency improvements (European Commission, 2020). The reform of the funding formula for tertiary education – which will be in force as of 2024 – plans to allocate a share of public funding according to performance targets (5 % in 2024, 10 % in 2025 and 20% from 2026)These will include study effectiveness, internationalisation, graduates’ careers and other quality metrics. As of 2023, colleges and the government will be able to sign contracts to get additional funding for mergers and other strategic objectives such as the development of research and/or study activities. Mergers will be in line with the plan prepared by the Centre for Quality Assessment in Higher Education. The revision of the mission of universities and colleges envisaged in the amended Law on research and studies could help further improve quality and incentivise differentiation between higher education institutions. The effectiveness of these reforms will depend on the rigorous use of the methodology to evaluate study quality.

Annex I: Key indicators sources

| Indicator | Source |

|---|---|

| Participation in early childhood education | Eurostat (UOE), , educ_uoe_enra21 |

| Low achieving eighth-graders in digital skills | IEA, ICILS |

| Low achieving 15-year-olds in reading, maths and science | OECD (PISA) |

| Early leavers from education and training | Main data: Eurostat (LFS), edat_lfse_14 Data by country of birth: Eurostat (LFS), edat_lfse_02 |

| Exposure of VET graduates to work based learning | Eurostat (LFS), edat_lfs_9919 |

| Tertiary educational attainment | Main data: Eurostat (LFS), edat_lfse_03 Data by country of birth: Eurostat (LFS), edat_lfse_9912 |

| Participation of adults in learning | Data for this EU-level target is not available. Data collection starts in 2022. Source: EU LFS. |

| Equity indicator | European Commission (Joint Research Centre) calculations based on OECD’s PISA 2018 data |

| Upper secondary level attainment | Eurostat (LFS), edat_lfse_03 |

| Public expenditure on education as a percentage of GDP | Eurostat (COFOG), gov_10a_exp |

| Public expenditure on education as a share of the total general government expenditure | Eurostat (COFOG), gov_10a_exp |

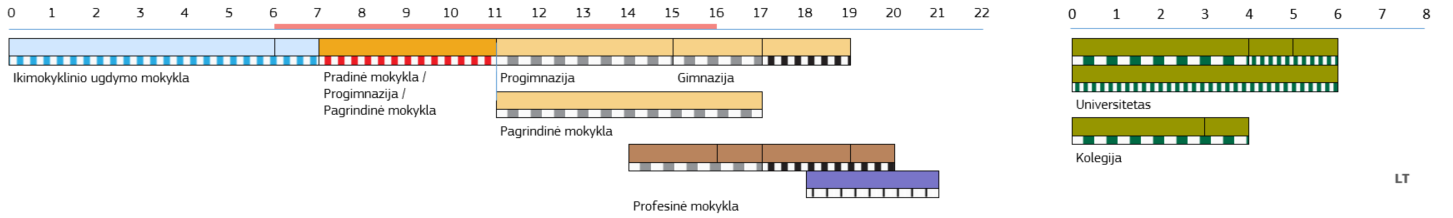

Annex II: Structure of the education system

Please email any comments or questions to:

Publication details

- Catalogue numberNC-AN-22-009-EN-Q

- ISBN978-92-76-55905-4

- ISSN2466-9997

- DOI10.2766/083907