Country Report

1. Key Indicators

Figure 1: Key indicators overview

| Denmark | EU | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 2021 | 2011 | 2021 | ||||||

| EU-level-targets | 2030 target | ||||||||

| Participation in early childhood education (from age 3 to starting age of compulsory primary education) | ≥ 96% | 97.6%13 | 97.6%20 | 91.8%13 | 93.0%20 | ||||

| Low achieving eighth-graders in digital skills | < 15% | 21.4%** | 16.2%18,†* | : | : | ||||

| Low achieving 15-year-olds in: | Reading | < 15% | 15.2%09 | 16.0%18 | 19.7%09 | 22.5%18 | |||

| Maths | < 15% | 17.1%09 | 14.6%18 | 22.7%09 | 22.9%18 | ||||

| Science | < 15% | 16.6%09 | 18.7%18 | 18.2%09 | 22.3%18 | ||||

| Early leavers from education and training (age 18-24) | < 9% | 10.3% | 9.8%b | 13.2% | 9.7%b | ||||

| Exposure of VET graduates to work-based learning | ≥ 60% (2025) | : | :u | : | 60.7% | ||||

| Tertiary educational attainment (age 25-34) | ≥ 45% | 38.6% | 49.7%b | 33.0% | 41.2% | ||||

| Participation of adults in learning (age 25-64) | ≥ 47% (2025) | : | : | : | : | ||||

| Other contextual indicators | |||||||||

| Equity indicator (percentage points) | : | 12.218 | : | 19.30%18 | |||||

| Early leavers from education and training (age 18-24) | Native | 10.0% | 9.7%b | 11.9% | 8.5%b | ||||

| EU-born | :u | :bu | 25.3% | 21.4%b | |||||

| Non EU-born | 15.1%u | 13.9%bu | 31.4% | 21.6%b | |||||

| Upper secondary level attainment (age 20-24, ISCED 3-8) | 70.5% | 75.4%b | 79.6% | 84.6%b | |||||

| Tertiary educational attainment (age 25-34) | Native | 39.7% | 49.1b | 34.3% | 42.1%b | ||||

| EU-born | 46.0u% | 60.6%b | 28.8% | 40.7%b | |||||

| Non EU-born | 25.0%u | 49.5%b | 23.4% | 34.7%b | |||||

| Education investment | Public expenditure on education as a percentage of GDP | 6.8% | 6.4%20 | 4.9% | 5.0%20 | ||||

| Public expenditure on education as a share of the total general government expenditure | 12.1% | 11.9%20 | 10.0% | 9.4%20 | |||||

Sources: Eurostat (UOE, LFS, COFOG); OECD (PISA). Further information can be found in Annex I and at Monitor Toolbox. Notes: The 2018 EU average on PISA reading performance does not include ES; the indicator used (ECE) refers to early-childhood education and care programmes which are considered by the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) to be ‘educational’ and therefore constitute the first level of education in education and training systems – ISCED level 0; the equity indicator shows the gap in the share of underachievement in reading, mathematics and science (combined) among 15-year-olds between the lowest and highest quarters of socio-economic status; b = break in time series, u = low reliability, : = not available, 09 = 2009, 13 = 2013, 18 = 2018, 20 = 2020.

Figure 2: Position in relation to strongest and weakest performers

2. A focus on teachers and educators

The increasing shortage of qualified teachers in Denmark risks undermining the quality of education. Education outcomes are highly dependent on the availability of a well-trained and motivated teacher workforce. Danish research has demonstrated a positive correlation between teachers’ subject knowledge and learning outcomes (VIVE, 2019). However, Denmark lacks qualified personnel in early childhood education and in primary and lower secondary schools (‘Folkeskole’). It forecasts that it will need an additional 13100 school teachers by 2030. (Danske Professionshøjskoler, 2021). Approximately one third of the currently employed educators in early childhood education and care (ECEC) lack teaching qualifications (EVA 2020) and only 10% of ECEC assistants have had training (EVA 2020). The situation is similarly worrying in primary and lower secondary schools in Denmark, where 16% of employed staff lack teacher training (EVA, 2021)1

Teacher training institutes fail to attract sufficient applicants; graduates increasingly leave the teaching profession. Training programmes for qualified ECEC staff have fewer applicants than other professions. Salary prospects play a major role (Union of pedagogues for children and young people (BUPL), 2022a). Since 2013, the share of newly recruited teachers for primary and secondary schools leaving the profession has continuously increased, resulting in 5 500 fewer graduates remaining in primary and lower secondary schools (Folkeskole) in 2020 (Arbejderbevægelsens Erhvervsråd, 2021b). In 2020, an estimated 28 390 trained teachers worked outside Folkeskolen. Close to 40% worked in public administration and just over a third in private primary schools. According to a recent survey2 there might be potential to attract more students as about 10% of young people enter higher education initially consider studying education and choosing teaching as a career. However, many change their mind due to an insufficiently attractive image of the profession as well as the working conditions (Danmarks Evalueringsstitut, 2022a). According to Eurydice, Danish teachers are – on average - more stressed than other teachers in the EU (53.5%, which is 6.7pps higher than the EU average)3. One out of three Danish teachers considers that the teaching job has a negative impact on mental and physical health (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2021).

The government supports lateral access routes and the professionalisation of ECEC teaching staff. A new 2.5-year long programme, ‘sporskiftemodel’, offers training for applicants holding a tertiary degree to become ECEC educators. The programme is designed to facilitate career change; it is one year shorter than the regular training and participants can also work in ECEC while training (Uddannelses- og Forskningsministeriet, 2022). Minimum quality standards for ECEC have been agreed on (with effect from January 2024), combined with government support for continuous education of both pedagogical assistants and educators. To access funding, municipalities must present a plan for improvements. Since the funding will not be enough to cover all municipalities, those with the lowest education coverage will be given priority (Børne- og undervisningsministeriet, 2020a). Denmark is investing EUR 27 million (DKK 200 million) in a new research programme on pedagogical issues in ECEC (Uddannelses- og Forskningsministeriet, 2022b).

Denmark has yet to reach the objective of the Folkeskole reform to ensure a high share of qualified teachers in all subjects. In primary and lower secondary education, the aim of the 2014 Folkeskole reform was to improve the quality of education by ensuring that by 2020, 95% of lessons would be taught by teachers qualified in the subject they teach. The date has now been postponed to 2025, and the evaluation of the reform showed that key targets were not met. The government decided in May 2022 to release EUR 8.8 million (DKK 65 million) in 2022/23 to provide students with more teaching hours, guidance and feedback. In September 2022, a broad poltitcal agreement in the parliament agreed on a new teacher education programme providing EUR 16.8 million (DKK 125 million) in 2023 and EUR 26.9 million (DKK 200 million) a year from 2023 onwards.

Continued professional development could help securing quality teaching. There is no legal obligation for ECEC staff and teachers in Denmark to follow continued professional development (CPD) (European Commission, 2021). However, municipalities are responsible for schools and required to draw up education plans with each school. School heads must discuss training opportunities with each teacher (European Commission/EURYDICE/2021). A recent study has shown that ECEC staff would benefit especially from continuous professional development (DEA 2022a). However, the take-up of CPD continues to fall (DEA, 2022b) for a variety of reasons4. For instance, teachers' needs for upskilling compete with their need to train in digital or environmental sustainability skills. Denmark's new digital strategy is investing EUR 27 million (DKK 200 million) in developing teachers’ digital skills, though the effectiveness of most recent training courses has not yet been evaluated.

3. Early childhood education and care

Denmark has a very high participation rate in early childhood education and care (ECEC), especially for under children under 3. The share of children between 3 years and the age of compulsory education in ECEC was 97.6% in 2020, above the 96% EU-level target and 3.7 pps. above the EU average. The share of children below the age of 3 in ECEC has been constantly above 60% for the last five years and 67.7% in 2020, far above the EU longer term average of around 35%. In addition, in Denmark basically all children attend ECEC for 30 hours or more and only 2.1% attend ECEC for less. Denmark has therefore by far exceeded the 33% Barcelona target.

The government is taking measures to improve ECEC quality. According to a survey covering 80 municipalities, the share of vulnerable children in early childhood education is increasing (Danmarks Evalueringsinstitut, 2022b). The government has placed an increased emphasis on reforming ECEC to improve its quality and also to battle uneven service provision since 2021 (see European Commission, 2021). The quality of service provision is a precondition for ECEC having a preventive effect, especially for children from disadvantaged socio-economic backgrounds. Quality also plays an important role in the 2022 agreement between the government and the association of municipalities on the financing of municipalities (Altinget, 2022a). The Danish Centre for Social Science Research (VIVE) on behalf of the Ministry of Children and Education is currently running a survey on quality that should provide additional data to feed into the agreement in 2023 (VIVE, 2021). An evaluation in spring 2022 confirmed that the updated and modernised curriculum in ECEC is welcomed and widely used (Danmarks Evalueringsinstitut, 2022c).

Denmark focuses on including green education in early childhood education. In 2018, the new strengthened pedagogical curriculum for ECEC formally introduced environmental sustainability for the first time as a key concept linked to the traditional focus on nature. Education on sustainability for young children has concentrated on children's democratic participation, on enabling children to experience nature and on developing their knowledge of the environment..

COVID-19 had some negative impact on early childhood education and care. As of September 2021 restrictions for ECEC were lifted. During the hight of the pandemic, in winter 2021/2022, there was nevertheless a high level of staff absenteeism due to illness, which had a partly negative impact on service quality. The government encouraged municipalities to adapt regulations (Altinget, 2022c) to local circumstances including allowing to temporarily close facilities in an emergency (Fagblade FOA, 2022).

4. School education

The rate of students leaving education and training early remains above the EU-level target and has even slightly increased. At 9.8% in 2021, early school leaving remained above the 9% EU-level target and increased by 0.5 pp. compared to the previous year. This is despite Denmark’s comprehensive approach to prevent students leaving school early, under which parents are required to ensure that their children receive education (European Commission, 2019). The share of early leavers among foreign-born young people is only 1.4 pps. higher than of their Danish-born peers, which is the smallest difference in the EU. The rate is 11.6% for boys and 8.1% for girls. At 5.8%, Denmark has a higher share of early leavers who are employed than unemployed (4.0%). This effect is stronger for young men, who have a higher employment rate than young women5. Interestingly, the share of young women leaving school early to join the labour market doubled between 2015 and 2021 but it increased only about a third for men.

Pupils in Denmark have good average basic skills and the share of underachievers is low. The share of 15-year-olds that underachieve in basic skills, as measured in the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) 2018, is well below the EU average. It is above or close to the 15% EU benchmark (mathematics 14.6%, reading 16.0% and science 18.7%). Since 2012, the share of underachievers remained broadly unchanged in all three tested competences. The share of top performers is close to the EU average and, while largely unchanged for mathematics and science (11.6% and 5.5% respectively), the rate almost doubled in the past decade for reading (now at 8.4%). Nevertheless, according to the 2020 final report, the Danish Folkeskolereform 2013 has not yet produced the desired results, neither in improving education outcomes nor well-being, both key goals of the reform (European Commission, 2021 and Vive 2020). The impact of students' socio-economic background on learning outcomes also remained unchanged. >

There are clear differences in Denmark between advantaged and disadvantaged schools. The difference in class teaching time between advantaged and disadvantaged schools as well as between private and public schools is particularly stark in Denmark (OECD 2022a). According to the OECD, more teaching time can translate into higher student achievement; a large-scale experiment in 2016 also demonstrated this in Denmark (Andersen et all 2016). The quality of teachers is also not evenly distributed throughout the country. For instance, principals in urban areas are more likely to help students develop their learning than those in rural areas (OECD 2022a). Additionally, comprehensively educated teachers are more likely to be employed in private than in public schools, which is also not unusual for other countries (0ECD 2022). According to the OECD PISA 2018 isolation index, Danish young people with a migrant background tend to be highly segregated in certain schools (0ECD 2019, OCED 2022b)

Denmark is advanced on digitalisation and students have strong basic digital skills, but more progress is needed in certain areas. In 2021, 80% of 16-19 year-olds in Denmark considered themselves to have basic or above-basic digital skills, 11 pps. above the EU average, but 15 pps. behind the top performer, Finland. 69% of 16-74 year-olds have basic skills and 37% have above-basic digital skills (EU average 54%/26%) (DESI 20226). Denmark's schools are very well equipped and connected7. This, together with digitally active teachers having already had experience with digital teaching and with established digital school platforms, enabled Denmark’s school system to move relatively easily to distance and hybrid learning during the COVID-19 pandemic (see European Commission 2020 and 2021 reports). This high degree of preparation is the result of consecutive, comprehensive and inclusive digital strategies involving several stakeholders (including the education sector) and the wider society. Currently, under the Digital Denmark Strategy for 2022-2026, the country reserves EUR 28.4 million (DKK 210 million) for education with a focus on investing in technology for primary and lower secondary education (Børne- og Undervisningsministeriet, 2022). Denmark has adopted a framework for technology in primary schools with the aim of creating a more practice-based school and supporting the development of teaching methods and competences, plus other measures for primary and lower secondary schools.

Nevertheless, there are areas for improvement. Danish teachers in public schools report higher needs for ICT training and those who need more intensive training tend to be located more in rural areas than in cities (OECD 2022a). Almost 9 out of 10 Danish teachers show high self-efficacy in using ICT for teaching. Denmark scored very high in the 2018 ICILS8 survey comparison. However, 6 out of 10 students still reached only level 2 or lower. The sufficient training of teachers could therefore be a factor with regard to the share of students with low digital skills. It may also affect the scope to further increase students' high level digital competences and move from digital applications to creation.

Denmark has a long-standing practice in green and sustainable education. Since the 1980s, the country has developed an interdisciplinary field for sustainable development primarily focusing on science and environmental pedagogy. However, integrating sustainability into education was more based on individual practice (including inclusion in curricula) than on national implementation strategies (European Commission, 2022). In the curriculum for primary and secondary education it is left to individual teachers to choose their learning material from the digitial platform emu.DK9 and to interpret education for sustainability without clear national guidance. Many private organisations partially supplement teaching material with a more consistent vision. In 2013, the concept of sustainability was integrated into the initial bachelor programme of teachers, again without a very clear definition. It remains lacking in continued professional development.

Figure 3: 16-19 year-olds with basic or above-basic overall digital skills, 2021 (%)

Box 1: Merkantil dannelse i et STEM perspektiv (‘Studying trade from a STEM perspective’ (ESF Project)

The aim of this project is both to increase the rate of completion of vocational training courses and - in the long term – to attract more young people to vocational training. Improving the transition after EUX studies10, when half of the students tend to drop out, is the main instrument for this. This should also help increase the number of skilled workers and ensure students develop a good mix of skills by supporting the work of Knowledge Centres and implementing and disseminating their information and policies.

In this context, the project develops new elective subjects for students to acquire STEM (science, technology, engineering and maths) competences and increase their competences in sustainability. It also increases the attractiveness of branding these type of training courses during the Danish Championship in Skills. It is based on close cooperation between businesses and schools and the effects are expected to last beyond the completion of the project. Between October 2019 and September 2022, the project involved 2 000 beneficiaries and produced good results by ensuring close cooperation between businesses and schools.

Budget: EU EUR 1.2 million (total support: EUR 2.4 million)

https://udviklingidanmark.erhvervsstyrelsen.dk/merkantil-dannelse-i-et-stem-perspektiv

5. Vocational education and training and adult learning

The Danish labour market faces sector-specific supply and demand mismatches. Current policies have failed to attract enough vocational education and training (VET) students. In particular, there are mismatches between the high demand for skilled labour and the structural low supply of VET graduates, since VET programmes fail to attract sufficient numbers of young people11. For several years, only around 20% of compulsory school graduates start a VET programme straight away, significantly below the government’s 2025 target of 30%. However, Denmark has very high share of the adult population in learning in a year, at 50% in 2016, already close to the 2030 target of 60%.

VET continues to be a high-priority issue in Denmark with implementation of reforms ongoing. With several measures and reforms from previous years ongoing, Denmark has created a national programme for choices in youth education to encourage more students to choose VET as their first choice. It is also investing in ten knowledge centres, a quality pool and a taximeter boost with more funding per student in vocational education. A further important strategic measure is the tripartite agreement to provide more apprenticeships and unequivocal responsibility from 2020, implementing several measures to increase the number of apprenticeships and provide all students with an apprenticeship.

Denmark has supported the establishment of climate-related VET schools to increase the future supply of green skills. The Danish Parliament passed the Danish Climate Act in 2020. Denmark's prospects of achieving its goal to become a climate-neutral society by 2050 depend to a large degree on having a sufficient number of skilled workers. This places VET at the core of the green and digital transitions. A new reform package for the Danish economy in early 2022 allocates EUR 13.4 (DKK 100) million annually for 2024-2029 and EUR 4 (DKK 30) million annually thereafter to climate-related schools. Though funding was already earmarked in 2021, implementing provisions were only agreed on in spring 2022, following applications from vocational schools and labour market training colleges. These green-skill schools should provide vocational education and training in sectors potentially contributing to the climate objectives by 2030. In the longer term, by 2050, this should also benefit the agricultural, transport, energy, construction, industrial and waste sectors.

The COVID-19 lockdown sped up the use of ICT-based education across age groups. The lockdown seriously affected adult education and learning in Denmark, and caused a fall in enrolment, despite constructive government initiatives. It also increased awareness of and the skills needed to use digital tools in teaching and learning. Many providers of continuing education and training had to close schools physically and embarked massively on ICT-based education. All education sectors, including adult education, used existing digital tools and platforms. Adjusting exam regulations made online exams possible. Educational institutions and teachers developed digital practices by taking a bottom-up approach. Central authorities supported these dynamics by adjusting regulations and providing additional funding.

The government stepped up initiatives to support action to integrate adult migrants and refugees. It set up Preparatory Basic Education (FGU), which has increased the options for young adults (up to 25). Regional FGU schools include both general and vocational educational programmes. The government and social partners extended the agreement on basic education for integration in early 2022. This temporary two-year programme run by the Ministry of Employment targets immigrants with a Danish residence permit. It is based on a combination of paid internships and school-based teaching and has been extended to 2023. The Ukraine crisis has challenged Danish society to respond to a sudden arrival of a large number of refugees. The government has taken action to integrate the refugees in Danish society, the labour market and education. Swift policy responses are supporting this goal, such as providing access to adult education, the basic education for integration programme and assistance to companies and educational institutions and to quickly assess the qualifications of Ukrainian applicants. Denmark's student support is also available for Ukrainian refugees, including for higher education.

6. Higher education

Denmark’s tertiary attainment rate is high and keeps rising but a wide gender gap remains. Since 2012, tertiary attainment has increased by 9.5 pps. to reach 49.7% in 2021 (a 2.6 pps. hike since 2020), potentially also related to the pandemic. In 2021, 57.8% of women had a tertiary degree compared to only 40.6% of men, leading to a wide gender gap of 17.2 pps, 6.1 pps. wider than the EU average. Tertiary attainment in cities is nearly double the rate in rural areas at 62.6% vs 33.7%; both above the EU average and resulting in a wide urban–rural gap. In 2021, the share of Danish and non-EU-born students was practically identical at around 49%, however the share of 25-34 year-olds from other EU countries reached 60.6%; hinting at Denmark's attractiveness as a place to study and work (see chart).

Figure 4: Tertiary educational attainment rate for the age group 25-34 by country of birth (%), 2021

Since 2015, Denmark has improved its share of STEM graduates markedly, but it still lags behind the EU average. In 2020, fewer students in Denmark graduated in STEM subjects with 23% 1.9 pps. fewer than the EU average. Nevertheless, the increase since 2015 is remarkable, when Denmark's share of STEM graduates among all graduates was the lowest in the EU. The share of women graduates among them, at 7.5%, was 2020 also 0.6pps below the EU average. Danish graduates’ choice of studies is broadly in line with other EU countries. However, there are some important exceptions with fewer graduates in education (5.2%, EU 9.7%) and close to half in services (3.3%, EU 5%). More young people graduate in health and welfare (20.6%) and in ICT (5.4%) than in the EU on average..

Recommendations for a substantial reform of Higher Education have been presented. In April 2022, after more than a year’s work, the Reform Commission presented the first part of their recommendations (New Reform Roads 1). They include (1) making Master's programmes more flexible, for example allowing universities to shorten their duration in many areas; (2) converting grants at Master's level into loans, with an increase in the available amount12; (3) investing in quality13; and (4) creating a new admission system to access tertiary education. The proposed recommendations also aim to improve the quality of teaching by increasing company-based teaching and strengthening competence development (Uddannelses- og Forskningsministeriet, 2022b).

Some study places will be reallocated outside the big cities. Parliament decided to reallocate 6.4% of all study places from big cities to other parts of the country by 2030 to create better educational opportunities all over Denmark. (Uddannelses- og Forskningsministeriet, 2022c). The initial phase (2021-2028) will be funded with EUR 109 million (DKK 805 million) to be followed by permanent funding of EUR 56 million (DKK 413 million), which will mainly go on increasing (by 107%) the support provided per student (Uddannelses- og Forskningsministeriet, 2022a).

Fewer applicants apply for higher education. 60 034 students enrolled in 2022, about 10% less compared to pre-pandemic 2019. The drop was even more important for educators in early childhood education and school teachers. These student numbers contrast to elevated numbers during the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2022, about 7 500 qualfied applicants were rejected in the admission procedure and about 8 500 candidates did not meet the enty requirements. Various reasons are identified for the decrease in enrolment. Future students might delay entering into higher education and work first or enjoy the habitual Danish ‘gap year’. Other students might already be in higher education as they advanced the beginning of their studies during the pandemic. The Danish Agency for Higher Education and Science is offering targeted support to rejected qualified applicants. About a third of the drop in student figures is attributed to the fact that 56 English-language programmes are not admitting students in 202214. This results from the government decision from June 2021 to reduce the number of English-language higher education programmes and places. Denmark has provided grants to foreign students, but many have not integrated into the Danish labour market upon graduation. (Uddannelses- og Forskningsministeriet, 2022d).

Annex I: Key indicators sources

| Indicator | Source |

|---|---|

| Participation in early childhood education | Eurostat (UOE), , educ_uoe_enra21 |

| Low achieving eighth-graders in digital skills | IEA, ICILS |

| Low achieving 15-year-olds in reading, maths and science | OECD (PISA) |

| Early leavers from education and training | Main data: Eurostat (LFS), edat_lfse_14 Data by country of birth: Eurostat (LFS), edat_lfse_02 |

| Exposure of VET graduates to work based learning | Eurostat (LFS), edat_lfs_9919 |

| Tertiary educational attainment | Main data: Eurostat (LFS), edat_lfse_03 Data by country of birth: Eurostat (LFS), edat_lfse_9912 |

| Participation of adults in learning | Data for this EU-level target is not available. Data collection starts in 2022. Source: EU LFS. |

| Equity indicator | European Commission (Joint Research Centre) calculations based on OECD’s PISA 2018 data |

| Upper secondary level attainment | Eurostat (LFS), edat_lfse_03 |

| Public expenditure on education as a percentage of GDP | Eurostat (COFOG), gov_10a_exp |

| Public expenditure on education as a share of the total general government expenditure | Eurostat (COFOG), gov_10a_exp |

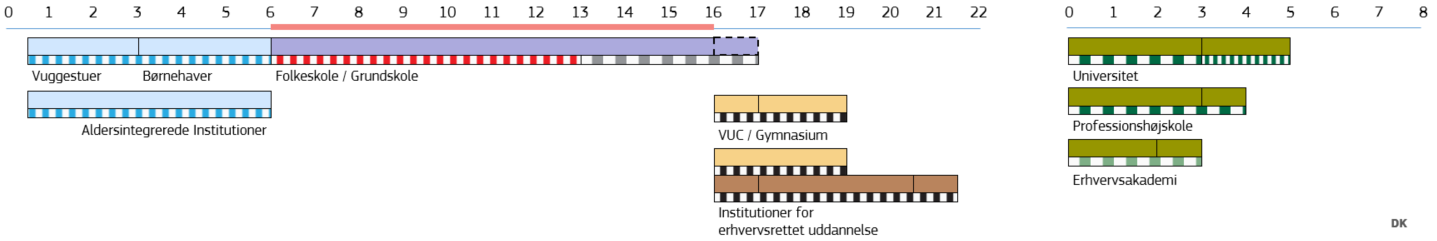

Annex II: Structure of the education system

Please email any comments or questions to:

Publication details

- Catalogue numberNC-AN-22-012-EN-Q

- ISBN978-92-76-55989-4

- ISSN2466-9997

- DOI10.2766/525876