List of acronyms

| AI | artificial intelligence |

| CAD | Canadian dollars |

| CETA | Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement |

| EU | European Union |

| EUR | euro |

| FDI | foreign direct investment |

| GDP | gross domestic product |

| GTA | Greater Toronto Area |

| ICT | information and communications technology |

| ICTC | Information and Communications Technology Council |

| IP | intellectual property |

| NAFTA | North American Free Trade Agreement |

| NAICS | North American Industry Classification System |

| NOC | National Occupational Classification |

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| R & D | research and development |

| US | United States of America |

How to use this report

The CETA information and communication technology (ICT) market entry guide offers an overview of the Canadian digital economy and describes the benefits of the European Union (EU) – Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) from the perspective of the ICT sector. This includes an overview of the ICT sector in Canada, Canadian trends in ICT, innovative growth areas, opportunities for EU businesses and market strategies for EU companies to enter Canada. The guide also presents an overview of existing challenges and barriers, and provides ‘tips’ for EU companies prior to entering the Canadian market.

Canada’s ICT sector is home to over 41 500 companies, encompassing everything from innovative startups to large multinationals. The Canadian ICT sector has been growing consistently for over a decade, and over the last 5 years it has outpaced the growth of the Canadian economy as a whole. As technology plays an increasing role across the economy, various levels of the Canadian government are investing in research and development (R & D) as well as adopting technologies to provide a better quality of life for Canadians. Interestingly, while the ICT sector only represents 5 % of the total Canadian economy, it is responsible for approximately 35 % of all private-sector R & D in Canada.

Several announcements and initiatives have taken place in recent years, which have propelled the Canadian ICT sector and ecosystem forward. These include the Innovation and Skills Plan, the introduction of Economic Strategy Tables and the creation of Innovation Superclusters. This guide highlights the priority areas across the Canadian digital economy. Fintech, advanced manufacturing, health tech, interactive digital media and others offer enticing opportunities for EU businesses.

A key milestone in the EU–Canada relationship came into force in the fall of 2017 with the ratification of CETA, which is widely considered to be one of Canada’s most progressive and ambitious trade initiatives. Although it eliminates duties on 98 % of goods currently traded between Canada and the EU, the benefits of CETA do not end with trade. CETA benefits not only manufacturers and producers but also the ICT sector overall, including ICT service providers. Additionally, it provides benefits to EU ICT businesses planning to enter Canada, including access to Canadian procurement markets, enhanced protection of intellectual property (IP) rights, enhanced worker mobility provisions and fair and equal treatment of EU ICT service providers.

Multiple EU business leaders interviewed in this study and other Information and Communications Technology Council (ICTC) research expressed an overall favourable perception of Canada, citing features like cultural symbiosis with Europe, the availability of a diverse and well-educated labour force, a growing tech sector and a welcoming culture. The EU–Canada relationship is long-standing and robust. Increased collaboration and business growth between the EU and Canada is favourable for both sides, and CETA can act as a critical cornerstone to advance these opportunities.

Note: All dollar figures are cited in Canadian dollars, unless otherwise noted. All euro figures have been converted from Canadian dollars using the InforEuro exchange rate system (June 2020).

1. An introduction to the EU–Canada relationship

The EU and Canada are among the world’s largest trading economies. The EU is the largest trading bloc in the world and the third-largest economy by purchasing power parity. Canada is a G7 country and the 16th-largest economy by purchasing power parity1. Built through hundreds of years of shared culture and history, as well as a commitment toward liberal values, Canada and Europe’s trade relationship is robust. The CETA agreement between the EU and Canada eliminated 98 % of pre-existing tariffs. When it entered into force in late 2017, trade in goods and services between Canada and the EU increased by 7.7 % compared to the previous year2. The EU was, at that time, Canada’s second-largest trade partner after the United States. In 2016, Canada–US trade was worth EUR 335.33 billion (CAD 508.2 billion) and trade with the EU was worth EUR 62.09 billion (CAD 94.1 billion). China was Canada’s third-largest trade partner, accounting for EUR 42.16 billion (CAD 63.9 billion) in trade. Collectively, these three trading partners (the EU, the United Stated and China) account for around two thirds of Canada’s total trade3.

In the wake of the coronavirus pandemic, polls suggest that Canadian attitudes toward the United States and China have hardened, which may spur a rejuvenated long-term interest in prioritising trade with the EU. A 2020 survey by Angus Reid found that only 38 % of Canadians had a favourable impression of the United States in 2020, compared to 49 % in 2018 and 68 % in 2009. Views of China are even harsher: only 14 % of Canadians held favourable views of China in 2020, compared to 48 % in 2017. In contrast, views of Japan and EU Member States remained high. For example, 82 % of Canadians have a favourable view of Germany, and over half (52 %) of Canadians surveyed identified the EU as a key priority for developing trade ties in 2020 – a 14 % jump from the previous year 4.

Growing trade between Canada and the EU is especially relevant to the ICT sector. ICT is one of the fastest-growing sectors in both Canada and Europe, and with the growing permeation of ICT products and services across industries, it has the potential to impact many other areas of economic activity. The CETA trade agreement has a range of provisions that are relevant to facilitate the relationships between Canadian and EU ICT companies. Such provisions – to be discussed later in more detail – include the elimination of tariffs as well as more robust enforcement of IP rights and standards and trademarks. By providing a common regulatory climate, CETA has the potential to boost the number of customers that EU companies can access effectively and better enable their operations in Canada.

Figure 1. Change (%) in ICT trade between Canada and the EU from the pre-CETA period 5

Source: Source: ICTC, 2020.

2. Canada’s ICT sector: an overview

The ICT sector makes a substantial contribution to Canada’s economy. In 2019, the ICT sector reached EUR 62.16 billion (CAD 94.2 billion), accounting for 4.8 % of Canada’s total output of over EUR 1 299 trillion (CAD 1 970 trillion)6. Over the last 5 years, the ICT sector’s growth has outpaced the growth of the Canadian economy. In 2019, the ICT sector grew by nearly EUR 2.96 billion (CAD 4.5 billion) – or 4.9 % – when compared with 20187.

The Canadian ICT manufacturing subsector is heavily export-oriented. About 78 %8 of ICT products manufactured in Canada were exported in 2018. Canadian exports of ICT goods increased by 1.3 % in 2018 to EUR 7.45 billion (CAD 11.3 billion) from 20179. When it comes to specific goods, exports of communications and electronic components equipment increased the most, while audio and video equipment had the steepest decline10. The United States, the Asia-Pacific region and the EU are Canada’s biggest trading partners, accounting for 70 %, 10 % and 9 % respectively of all ICT goods exported from Canada. The ICT services subsector is highly domestically oriented. In 2017, exports of communications services grew by 1.8 %, totalling EUR 1.6 billion (CAD 2.5 billion), while software and computer services grew by 6.1 % to reach EUR 5.27 billion (CAD 8 billion)11.

The ICT sector’s R & D expenditures totalled EUR 4.09 billion (CAD 6.2 billion) in 2018, an increase of 2.2 % from 201712. The ICT sector is responsible for approximately 35 % of all private-sector R & D in Canada.

Canada is home to a world-class knowledge-intensive workforce. Over 50 % of ICT workers currently hold a university degree, compared to 30.5 %13 who hold a university degree across all other Canadian industries. Employees in the ICT sector earn on average over EUR 51 330 (CAD 77 800) per year, which is almost 50 % higher than the Canada-wide average, as of 2018. In 2019, there were more than 698 900 professionals employed across the ICT sector, accounting for 3.7 % of Canada’s total employed workforce14. Some 500 600 of those 698 900 jobs are ICT jobs15. Employment in several ICT occupations experienced high growth in 2019. The top growth areas were data and information analytics, programming, interactive media development and electrical engineering/installation16.

2.1. Defining the ICT sector

Definitions of the tech sector vary according to source. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) definition, dating from 1998, is as follows: ‘A combination of manufacturing and services industries that capture, transmit, and display data and information electronically.’

ICTC currently defines the ICT sector as a collection of ‘businesses that fall under certain digital-based industries.17’ In more practical terms, ICTC defines the sector according to the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS)18, a classification of business establishments in North America. A total of 19 NAICS codes are used to define the ICT sector, including the following key industries:

- software publishers,

- motion picture and video industries,

- satellite telecommunications,

- computer systems design and related services.

The distinction between the ICT sector and ICT employment is noteworthy. While the ICT sector is defined by a grouping of ICT industry codes (see Table 1), ICT employment is defined by a grouping of occupational codes (see Table 2), irrespective of whether employees in these codes work in ICT industries. An example of an ICT worker within the ICT sector can be a software engineer working for a telecommunications company, whereas an ICT worker may work in a non-ICT industry, such as a cybersecurity professional working for a tourism company.

ICTC defines ICT employment according to 30 National Occupational Classification (NOC)19 codes, which include:

- engineering managers,

- computer and information systems management,

- software engineers and designers,

- computer and information systems managers,

- web designers and developers.

Table 1. Summary of industries in the ICT sector (NAICS codes)

|

Index |

North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) |

ICT subsector |

|

1 |

3333 |

Commercial & service industry machinery manufacturing |

|

2 |

3341 |

Computer & peripheral equipment manufacturing |

|

3 |

3342 |

Communications equipment manufacturing |

|

4 |

3343 |

Audio & video equipment manufacturing |

|

5 |

3344 |

Semiconductor & other electronic component manufacturing |

|

6 |

3345 |

Navigational, medical & control instruments manufacturing |

|

7 |

3346 |

Manufacturing and reproducing magnetic and optical media |

|

8 |

4173 |

Computer & communications equipment & supplies wholesale distribution |

|

9 |

5112 |

Software publishers |

|

10 |

5121 |

Motion picture and video industries |

|

11 |

5171 |

Wired telecommunications carrier |

|

12 |

5172 |

Wireless telecommunications carrier (except satellite) |

|

13 |

5174 |

Satellite telecommunications |

|

14 |

5179 |

Other telecommunications |

|

15 |

5182 |

Data processing, hosting, and related services |

|

16 |

5191 |

Other information services |

|

17 |

5415 |

Computer systems design & related services |

|

18 |

7115 |

Independent artists, writers and performers |

|

19 |

8112 |

Electronic & precision equipment repair & maintenance |

Table 2. Summary of Core ICT Occupations (NOC codes)

|

INDEX |

National Occupation ClassificatioN (NOC) |

Occupation title |

|

1 |

0015 |

Senior managers – trade, broadcasting and other services |

|

2 |

0211 |

Engineering managers |

|

3 |

0213 |

Computer and information systems managers |

|

4 |

0601 |

Corporate sales managers |

|

5 |

1123 |

Professional occupations in advertising, marketing and public relations |

|

6 |

1253 |

Records management technicians |

|

7 |

2133 |

Electrical and electronics engineers |

|

8 |

2147 |

Computer engineers (except software engineers and designers) |

|

9 |

2148 |

Other professional engineers |

|

10 |

2161 |

Mathematicians, statisticians and actuaries |

|

11 |

2171 |

Information systems analysts and consultants |

|

12 |

2172 |

Database analysts and data administrators |

|

13 |

2173 |

Software engineers and designers |

|

14 |

2174 |

Computer programmers and interactive media developers |

|

15 |

2175 |

Web designers and developers |

|

16 |

2241 |

Electrical and electronics engineering technologists and technicians |

|

17 |

2281 |

Computer Network Technicians |

|

18 |

2282 |

User support technicians |

|

19 |

2283 |

Information systems testing technicians |

|

20 |

4163 |

Business development officers and marketing |

|

21 |

5223 |

Graphic arts technicians |

|

22 |

5224 |

Broadcast technicians |

|

23 |

5241 |

Graphic designers and illustrators |

|

24 |

7241 |

Electricians (except industrial and power system) |

|

25 |

7242 |

Industrial electricians |

|

26 |

7243 |

Power system electricians |

|

27 |

7244 |

Electrical power line and cable workers |

|

28 |

7245 |

Telecommunications line and cable workers |

|

29 |

7246 |

Telecommunications installations and repair workers |

|

30 |

7247 |

Cable television service and maintenance technicians |

2.2. Canadian trends in the ICT sector

The ICT sector is dynamic. It experiences both substantial innovation and internal disruption – meaning that the definition of what is and is not considered ‘ICT’ is fluid – and creates larger impacts for the wider economy. Increasingly, it is challenging to decouple ICT from the broader economy: the coronavirus pandemic has ushered in a large-scale shift to remote work, and online business has reinforced this trend.

2.3. Key ICT innovations

The rapid and sustained growth of the ICT sector and ICT across the economy is primarily driven by technological innovations that are generating some form of economic value across the economy.

Many ICT industries have had success selling these technologies directly to consumers, both in and outside of Canada.

Figure 2. Technology subject to commercialisation and innovation in the last decade

2.4. Growth in ICT subsectors

Many innovations in the ICT sector have found applications outside the ICT sector. Some technologies, such as artificial intelligence (AI) and blockchain, are especially broad in applications and potential areas of impact. On the other hand, certain industries have proven particularly ripe for innovation. This has given rise to a vibrant ecosystem of tech-based subsectors. In Canada, the following technology subsectors have seen notable growth and are expected to continue to drive innovation:

- clean technology (including clean energy generation, waste management);

- clean resources (natural resource extraction via clean technology);

- health tech and biotechnology;

- ag-tech (technology used to maximise outputs in the agriculture sector);

- fintech;

- interactive digital media (including video games, animation, visual effects, mixed reality);

- advanced manufacturing (including 3D printing, manufacturing automation).

2.5. Smart cities and digital governance

As technology plays an increasing role in the home and workplace, various levels of government in Canada are interested in adopting these technologies to provide a better quality of life and governance for Canadians.

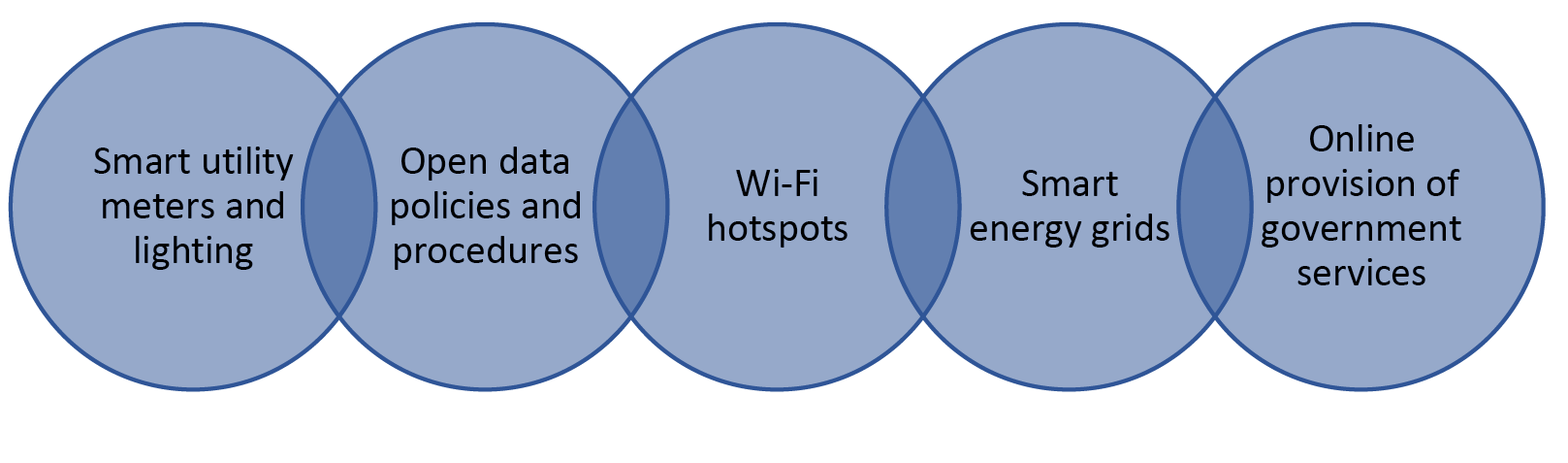

Some of the most zealous adopters of digital technologies have been municipalities, many of which have partnered with technology companies to pilot innovative projects. Key examples include the winners of Infrastructure Canada’s ‘Smart City Challenge,’ the city of Guelph’s circular economy project; Montreal’s project to enhance food access and mobility options; Bridgewater’s project to reduce energy poverty and encourage clean energy use; and Nunavut’s suicide prevention project20. The concept of a ‘smart city’ has recently caught on in Canada, and cities across the country are undertaking projects that touch on several related areas, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Areas subject to Canadian projects on development and integration

ICTC is investigating smart city developments and labour market needs across Canada via a multi-year project. These activities are grounded in six ‘smart city priority areas’: smart infrastructure, smart environment & energy, smart health & wellbeing, smart government, smart mobility, smart regulation21.

2.6. Creative destruction and talent shortages

The adoption of new technologies that streamline business processes creates disruption across the economy. Nowhere is this more evident than in the ICT sector itself. Studies have yielded vastly different estimates of the number of jobs affected by automation over the long term, from inconsequential effects on overall jobs to hundreds of millions of job losses22. As a result, ICTC estimates that businesses in the ICT sector and broader digital economy – as well as digitally skilled workers – are better prepared to withstand this disruption. Prior to COVID-19, which created considerable shock waves across the economy, ICTC estimated that the demand for talent across the digital economy would reach more than 193 000 workers between 2019 and 2022. The pandemic reduced this demand by nearly 24 %. Under ICTC’s new baseline scenario, the digital economy is expected to see a demand for 147 000 workers by 2022, with total employment reaching nearly 2 million (down from an original forecast of 2.1 million). However, despite the pandemic-driven shrinking demand, the digital economy, and in particular the ICT sector, has proven remarkably resilient in comparison to many other areas of the economy. According to ICTC’s analysis, by July 2020 the gross domestic product (GDP) of the ICT sector only decreased by 1 % from its February peak (compared to a 9 % drop in the overall economy). Moreover, employment in the ICT sector actually saw growth despite the pandemic, climbing by nearly 10 % from February to July 2020.

2.7. Key players

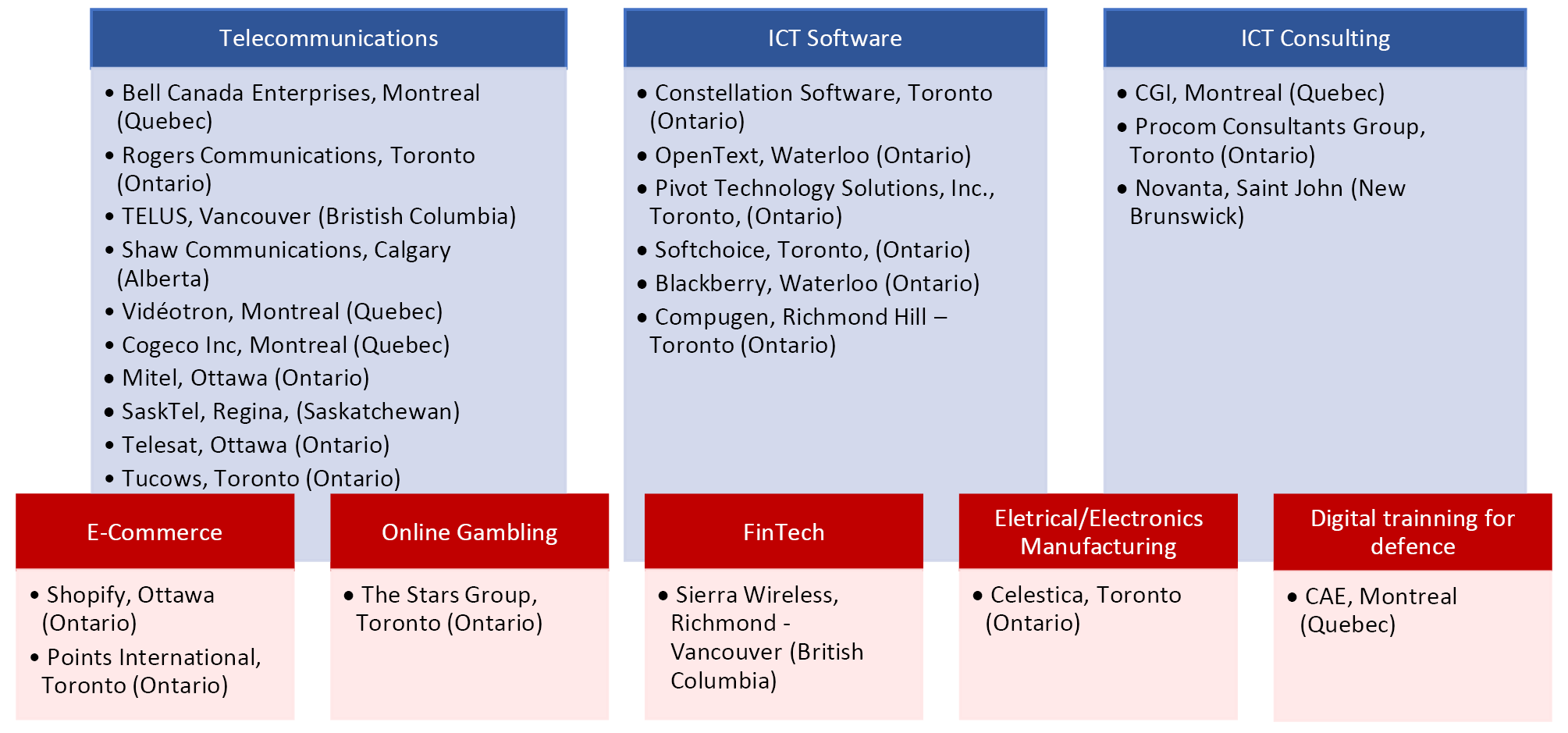

Canada’s ICT sector is home to over 41 500 companies, including everything from innovative startups to large multinationals. Yet, around 85 %23 of the ICT businesses in Canada are small, employing 10 people or less. Only 1.6 %24 of Canadian ICT businesses employ more than 100 people. In all, 37 000 companies or around 89.9 % of all ICT businesses fall within the software and computer services industries space, 4.5 % within ICT wholesaling, 2.2 % within ICT manufacturing and the other 3.4 % within the communications services industry25. Figure 4 shows Canada’s 25 biggest ICT and ICT-adjacent companies, according to the 2019 publication of the Branham 25026.

Figure 4. Canada’s 25 biggest ICT and ICT-adjacent companies

The ICT sector in Canada is represented by a variety of national, provincial and regional organisations, industry associations and other stakeholders. Combined, these organisations facilitate the growth of the local Canadian ICT market and can also provide connections and assistance for EU ICT businesses seeking to expand to Canada. A full list of such resources is available in Annex I.

2.8. Coronavirus shocks and questions for the future

The COVID-19 pandemic shocked the global ICT manufacturing sector due to its disruption of the supply chains. However, ICTC research suggests that the digital economy – including the larger ICT services sector – has been considerably less affected than many other sectors. Indeed, organisations such as Amazon and Facebook were among the first major corporations to switch to universal remote work and, in some cases, the coronavirus has even heightened the demand for certain ICT services. Key examples include the surge in demand for cybersecurity services and professionals and machine learning engineers. Additionally, in the first months of the coronavirus – and specifically as lockdowns took shape across the country – the demand for telecommunications services and videoconferencing platforms, video games and animated content all saw a massive surge in demand.

3. CETA provisions affecting the ICT sector

After CETA came into effect, there was a substantial growth in trade between the EU and Canada. Owing to expanded opportunities offered by the agreement, along with a shared history and cultural proximity, there is significant potential for growth and increased partnership opportunities between the EU and Canadian ICT sectors. In general, CETA’s provisions include tariff reduction, the enabling of labour mobility, access to government procurement and regulatory cooperation.

3.1. ICT-Specific regulations

Chapters 15 and 16 of CETA explicitly address the ICT sector.

In Chapter 15, the EU and Canada commit to giving each other’s businesses ‘fair and equal access’ to public telecommunications networks and services. The chapter includes a commitment to ‘competitive safeguards’ to ensure a competitive playing field in the telecommunications field. Specifically, each trade partner commits to taking ‘appropriate measures’ to prevent anti-competitive actions from a major supplier or a group of suppliers. The anti-competitive behaviour identified is broad: it includes engaging in anti-competitive cross-subsidisation, using information received from competitors to achieve anti-competitive results, and not providing commercial relevant information and technical information about essential facilities to other service suppliers27.

In Chapter 16, the EU and Canada promise to cooperate on issues related to e-commerce, such as combatting spam. It includes roles for protecting personal information and pledges that services traded online between Canada and the EU will not be subject to customs duties.

According to Reservation I-C-9 (from the Schedule to Annex I of CETA), foreign investment in ‘facilities-based telecommunications services suppliers’ in Canada is restricted to a maximum cumulative total of 46.7 %. Foreign investment may not make up more than 20 % of direct investment and 33.3 % of indirect investment in such companies. These service suppliers must be controlled by Canadians and 80 % of board members must be Canadians.

3.2. Tariffs

Prior to CETA, only a quarter of Canadian products exported to the EU were duty-free. CETA has eliminated 98 % of pre-existing tariffs on goods traded between the EU and Canada28, including all tariffs on industrial products29, i.e. products consumed by businesses rather than individual consumers. The removal of tariffs on industrial products applies to a wide class of goods, including clean technology products and industrial ICT equipment such as transmission apparatuses, fibre optics and sound and signalling apparatuses30.

These tariff removals will be particularly helpful to European suppliers of telecommunications equipment. Ten of Canada’s top 25 ICT organisations are in the telecommunications sector31. Canada is a large, affluent market for industrial telecommunications and has some of the fastest cellular connection speeds in the world32. However, there continue to be large gaps in service quality between urban and rural areas33. EU companies specialising in the export of telecommunications-related equipment (particularly if related to 5G) will find a robust and growing market for their products in Canada. The Canadian government has identified the improvement of connectivity nationwide to be of national interest and will host spectrum auctions in 2021 to distribute rights to 200 Hz of 5G bandwidth34. Since Canadian opinion of the United States is at a four-decade low35, and most Canadians are opposed to any Chinese involvement in the new 5G infrastructure36, European telecom exporters are gaining improved access to Canada at a particularly opportune time.

3.3. ICT services

CETA facilitates trade in services between the EU and Canada. Article 9 of CETA requires that each of the two signatories (the EU and Canada) treat foreign services and service suppliers no less favourably than they would their own service supplies. In this regard, CETA prohibits ‘arbitrary and unjustifiable discrimination’ toward foreign companies, while allowing signatory parties a measure of independence in regulating sectors. Article 9 concludes that neither nations, provinces, territories, regions or municipalities may adopt measures that limit service supplies, value on service transactions and total number of service operations from external countries. The only effective exception to this article is found in Reservation I-C-9, which caps foreign investment for telecommunications providers that comprise more than 10 % of industry revenue and insists that their boards have 80 % Canadian representation37.

Chapter 11 provides a framework that allows Canada and the EU to recognise each other’s professional qualifications. Specifically, the framework permits ‘relevant authorities or professional bodies’ in Canada and the EU to negotiate in this regard. Chapter 16 of CETA stipulates that online services traded between Canada and the EU are not subject to customs duties.

3.4. Labour mobility

CETA recognises new categories of business travellers. These include short-term business visitors, contract service suppliers and independent professionals. Contract service providers and independent professionals refer to people who travel between Canada and the EU to complete a service or contract for a key service sector. They are eligible for work permits for up to 12 months, with the possibility of a 12-month extension38.

CETA also allows for other key personnel – normally business visitors or investors, as well as senior intra-company transfers or trainees – to obtain work permits for up to 3 years. Notably, many such personnel are exempt from completing a Labour Market Impact Assessment in order to obtain a work permit39. This is a critical component, as previous ICTC research40 found the assessment to be a key barrier for ICT businesses seeking to source skilled international talent.

This freedom of travel can allow for the ramp-up of meetings, consultations, R & D, market research and sales and relationship-building. The key desired outcome of this provision is to make it easier to conduct business deals between companies and to build transatlantic teams and relationships.

Additional information on labour mobility between the EU and Canada can be found in the CETA themed report on mobility of professionals.

3.5. Government procurement

While companies were previously able to bid on government contracts to some degree, Chapter 19 of CETA grants access to procurement contracts at every level of government – national, regional, provincial and local. The current public procurement offer is the most comprehensive that Canada has ever made (including NAFTA) and opens procurements in all but two sectors: energy utilities (in Ontario and Quebec) and public transport. Canada has committed to publish all bidding opportunities centrally online, allowing EU companies a single access point for all procurement opportunities in Canada41.

More information on public procurement can be found on the public procurement guides available at: https://trade.ec.europa.eu/access-to-markets/en/country-assets/tradoc_158655.pdf and https://trade.ec.europa.eu/access-to-markets/en/country-assets/tradoc_158939.pdf.

3.6. Regulatory cooperation

CETA includes the Protocol on the Mutual Acceptance of the Results of Conformity Assessments. This protocol does not necessarily require acceptance of the respective party’s technical regulations, but rather allows for the recognition of accreditation bodies and conformity assessment bodies. In essence, these bodies allow for regulatory conformity to be tested outside of the export destination. For example, Canadian and EU companies under certain product categories (including ICT) can have their products tested for conformity and certified for each other’s market42. This can reduce marketing delays for producers and reduce barriers to exports.

3.7. Intellectual property and copyright

Several provisions in CETA are related to IP and copyright. According to the agreement, Canadian exporters to the EU will implement more stringent measures to cut down on circumvention devices. Companies from both Canada and the EU will comply with a range of other regulations such as the Trademark Law Treaty, the Hague System for the International Registration of Industrial Designs and the Patent Law Treaty. Enhanced patent protection will be implemented for pharmaceutical and industrial designs. Key provisions are patent term restoration where delays are encountered when obtaining regulatory approval – a frequent occurrence in the pharmaceutical industry – and the right of appeal as it relates to dual litigation43.

3.8. CETA’s impact on Canada’s ICT sector

CETA’s tariff eliminations reduce overall business costs for Canadian companies seeking to export to the EU. For Canada, CETA opens a market consisting of hundreds of millions of potential customers and 27 national economies44. New protocols on labour mobility can also enable Canadian ICT businesses to build relationships with EU businesses and customers along a much faster timeline than in the pre-CETA period. CETA provides preferential access to the EU government procurement market, which is estimated to be worth more than EUR 1.3 trillion45.

In 2017, the year that CETA was signed, Canada was the third-highest source of foreign direct investment (FDI) in the EU after the United States and Switzerland. Canada accounted for nearly 5 % of FDI in the EU46. Canada also received around 4.5 % of EU foreign investment in 201747.

CETA coincided with a rise in trade between Canada and the EU. In the year following CETA’s entry into force, exports of goods and services from Canada to the EU rose by 3.9 %. There was a rapid rise in the export of technical products from Canada to several EU Member States. For example, merchandise exports in ‘scientific and precision instruments’ to Austria rose by 38.5 %. Scientific and precision instrument exports to Denmark rose by 13.5 % and those to Germany rose by 7.7 %48.

3.9. CETA’s impact on the EU ICT sector

Canadians have a positive attitude toward building trade relations with Europe across all sectors. CETA has coincided with an increase in Canadian import of technical products49. For example, Canadian imports of ‘computer and electrical manufacturing’ products from the EU increased by 11 % between 2015 and 201950.

Table 3. Key CETA benefits for the EU ICT sector

|

Market access and tariff elimination |

The elimination of tariffs of exports to Canada also benefits EU companies seeking to export to Canada. By accelerating exchange between Canada and the EU, EU companies can test the Canadian market for interest in EU products and services, while also leveraging the Canadian market to eventually enter the United States or other markets of geographical proximity like Mexico and South America. |

|

Public procurement |

CETA provides EU companies with access to an additional EUR 29.03 billion (CAD 44 billion) in procurement market coverage. The estimated procurement market gains are EUR 502.80 million (CAD 762 million). Between 2009 and 2015, only 2.2 % of the value of Canadian procurement contracts was awarded to EU Member States, compared to 7.5 % for the United States. Most new procurement opportunities available under CETA are at the subnational level51. |

|

Labour mobility |

Loosened mobility provisions will also allow EU investors, as well as those who establish operations in Canada, to obtain work permits in Canada more easily. For example, business investors, intra-company transferees and other critical personnel from EU companies can more easily access longer-term work permits in Canada via CETA. This reduces the layers of administration and bureaucracy needed in order to attract and enable skilled personnel to enter the Canadian market. New protocols on labour mobility can also enable Canadian ICT businesses to build relationships with EU businesses and customers according to a much faster timeline than the pre-CETA period. |

|

Investment |

EU businesses can benefit from a relaxation of rules for foreign investment in Canada. Under CETA, in conjunction with the Investment Canada Act, the investment threshold requiring a net benefit formal review has been raised from EUR 233.58 million to EUR 0.89 billion (CAD 354 million to CAD 1.5 billion)52. This change reduces the total number of EU investments requiring formal review and streamlines the process for most EU organisations seeking to export to Canada. |

|

Regulatory cooperation |

The Protocol on the Mutual Acceptance of the Results of Conformity Assessments allows for the recognition of accreditation bodies and conformity assessment bodies. Canadian and EU companies under certain product categories (including ICT) can have their products tested for conformity and certified for each other’s market53. This can reduce marketing delays for producers and reduce barriers to exports. |

4. Key trends and opportunities for EU businesses

4.1. The innovation and skills plan

In recent years, the Government of Canada has announced several initiatives to propel the Canadian ICT sector and ecosystem forward. This will be beneficial for EU businesses as well.

In 2017, the Government of Canada announced the Innovation and Skills Plan. This plan is an ambitious effort to make Canada a world-leading centre for innovation, to create well-paying jobs across the country and to help strengthen and grow the middle class54. The plan adheres to a set of clear targets which consist of the following:

- growing Canada’s goods and services exports by 30 % by 2025;

- increasing the clean technology sector’s contribution to Canada’s GDP;

- doubling the number of high-growth companies in Canada, particularly in the digital, clean technology and health technology sectors, from 14 000 to 28 000 by 2025;

- equipping Canadians with the tools, skills and experience they need to succeed in the marketplace while also attracting global talent55.

The success of the plan is tracked across four areas: people and skills; research, technology and commercialisation; investment, scale-up and clean growth; and programme simplification.

As a part of the Innovation and Skills Plan, the Government of Canada also announced the creation of six Economic Strategy Tables. These tables are a new model for collaboration between industry and government to identify growth opportunities in advanced manufacturing, agri-food, clean technology, digital industries, health/bioscience and the clean resources sectors. The ICT sector was recognised as one of the growing areas under the Digital Industries Table. In 2019, the government announced that it would be adding a seventh table focused on tourism.

Figure 5. The Innovation and Skills Plan’s Economic Strategy Tables

As mentioned, 85 % of Canadian ICT firms currently employ fewer than 10 people. In the first Digital Industries report, the Government of Canada set up an ambitious plan to expand the number of large Canadian digital companies. The goal is to double the number of businesses earning CAD 1 billion or more in annual revenue (from 13 to 26 businesses) by 2025. In order to achieve this growth target, four recommendations were proposed: scale up Canadian businesses; attract, retain and support skilled talent; transform Canada into a digital society; and leverage IP and promote the value of data.

Piggybacking on these initiatives, in June 2019 the Government of Canada and the EU signed an administrative arrangement between the EU and Canada creating a transatlantic cluster collaboration56. Thanks to this arrangement, the 26 EU cluster organisations and Canada’s five innovation superclusters will have more opportunities to strengthen collaboration and form strategic business partnerships with overseas counterparts (see Figure 6).

4.2. The innovation superclusters

In 2018, the Government of Canada announced a EUR 626.86 million (CAD 950 million) business-led Innovation Supercluster initiative that includes five superclusters: the Digital Technology Supercluster; the Protein Industries Canada Supercluster; the Next Generation Manufacturing Supercluster (NGen); the AI-Powered Supply Chains Supercluster (SCALE.AI); and the Ocean Supercluster. The Innovation Superclusters initiative is projected to create in excess of 50 000 jobs and contribute more than EUR 32.99 billion (CAD 50 billion) in GDP to Canada’s economy over a 10-year period57. The initiative represents a collaboration between 450 small, medium-sized and large companies, 60 academic institutions and 180 other participants from five high-potential sectors.

Figure 6. Canadian Innovation Superclusters

|

DIGITAL TECHNOLOGY SUPERCLUSTER |

|

Based in British Columbia. Areas: virtual, mixed and augmented reality, big data analytics, quantum and cloud computing, and machine learning. Goal: boost competitiveness in precision health, manufacturing, resource and environmental technologies58. Projects: seven projects focused on improving service delivery and efficiency in the natural resources, precision health and industrial sectors59 and another eight capacity-building projects announced in early 2020, focusing on promoting skills development, diversity and inclusion in the technology sector, and the attraction of students to careers in digital technology60. The Digital Technology Supercluster’s strategic plan for 2018–202361 states that it will ‘continue to connect with global leaders in diversity and inclusion, including the European Union, UN Women and the WE EMPOWER Programs’62. The plan also highlights the following goal: ‘Develop strategic alliances with other global innovation hubs in North America, Asia, Europe, Africa and South America’63 (but doesn’t offer more detail on these alliances or a strategy for developing them). |

|

OCEAN SUPERCLUSTER |

|

Based in Atlantic Canada. Areas: marine renewable energy, fisheries, aquaculture, oil and gas, defence, shipbuilding, and transportation64. Goal: strengthen the ocean sector by harnessing emerging technologies such as autonomous marine vehicles, digital sensors and monitoring, marine engineering and biotechnologies. Projects: first project (June 2019) led by a Saint-John-based marine technology company in collaboration with a number of other cluster partners, with a focus on the development of an underwater technology service hub that will provide high-resolution mapping of the ocean floor65. At the beginning of 2020, the Ocean Supercluster announced another project in the Atlantic region to foster the creation and growth of ocean technology companies and increase the industrial use of marine technologies66. The supercluster supports collaborative activities with Germany, the Netherlands, Norway and the United Kingdom67. In addition to the collaborative activities supported by the supercluster, the Province of Nova Scotia has developed a Nova Scotia–Europe Engagement Strategy, highlighting avenues for closer collaboration with the EU. This document specifically states the goal of working closer with the EU and ‘with government, academia, and the private sector to promote the Ocean Supercluster and encourage new investment, research, and commercial partnerships in the ocean economy.68’ |

|

PROTEIN INDUSTRIES SUPERCLUSTER |

|

Based in Prairie provinces. Areas: agri-food technologies including genomics, processing, and information technology (IT) used to produce a variety of plant protein and plant-based coproducts. Goals: strengthen the agriculture and food-production sectors69. Projects: first project (June 2019) was geared toward the application of advanced technologies for improving oil and protein ingredient values in canola and hemp crops70. In the beginning of 2020, the Protein Supercluster announced four new projects. The first one focuses on the commercialisation of new highly soluble, highly functional pea and canola protein isolates71. The second project focuses on the production of high-protein canola hybrids for both human consumption and animal feed72. The third project focuses on the uses of AI tools to make farming more transparent, efficient and profitable, with the objective of reinforcing Canada’s reputation as a global supplier of sustainable and traceable food73. The fourth project aims to help Canadian organic growers and processors by developing a new use for by-products from the pulse processing industry by turning waste into fertiliser, which will ultimately deliver nutrients back into plants74. The supercluster’s strategy does not make specific mention of international efforts or collaboration prospects with European countries, but it supports collaborative activities with France and Germany75. |

|

NEXT GENERATION MANUFACTURING SUPERCLUSTER |

|

Based in Ontario. Areas: machine learning, advanced robotics and 3D printing76. Goals: incorporating advanced technologies in product development and process design across the manufacturing sector. Projects: first project (August 2019) for development of viral vectors using advanced manufacturing techniques. Viral vectors are molecular tools currently used to deliver genetic material into patients suffering from late-stage cancers and rare or inherited genetic disorders77. The supercluster’s 5-year strategy lists broad international goals such as facilitating ‘advanced manufacturing partnerships between companies and clusters both within Canada and internationally.78’. While it does not make specific mention of a collaboration strategy with Europe, the supercluster supports collaborative activities with Belgium and Germany79. |

|

AI-POWERED SUPPLY CHAINS SUPERCLUSTER (SCALE.AI) |

|

Based in Quebec. Areas: ICT, AI technology and robotics technology80. Goals: integrating the manufacturing, transportation and ICT sectors in creating intelligent supply-chain networks primarily through the application of AI and robotics technology. Projects: first set of projects (June 2019) focused on the incorporation of AI for reducing costs and improving efficiencies in the consumer goods, farming, telecom and shipping sectors81. In January 2020, the supercluster announced another new project that brings together over 60 partner organisations, to explore how AI can help reduce costs and improve efficiencies. The projects are using AI to modernise processes and enhance productivity in the shipping, retail trade, aeronautics and healthcare sectors82. The AI-Powered Supply Chains Supercluster does not have a specific strategy focus that addresses internationalisation, but its 5-year strategy foresees forming better alliances with Europe. For example, it states that it will ‘develop new partnerships with best-in-class ecosystem players … across the EU, Europe, and Asia’83. While no further information is available on collaboration opportunities for EU companies with the supercluster, the opportunity may nevertheless exist for interested and qualifying parties. |

4.3. Market entry strategies

Entering a new market is a venture supported by several smaller initiatives and undertakings during the pre-market-entry stage. While there are no guaranteed ‘dos and don’ts’ in this process, important steps for entry can include the following.

- The entering company has completed extensive market research on the host country in order to understand factors, including but not limited to the following: local culture and important cultural considerations84, local consumer appetite for the project, appropriate price-setting (what the market will bear)85, relevant barriers to entry, identification of major competitors and completion of a thorough competitive analysis (including a SWOT analysis), and potential marketing and rollout strategies. In the context of Canada, price-setting must also take into account whether goods imported from outside of Canada are subject to any permits, restrictions or regulations. The Canadian Border Services Agency (CSBA) offers a Reference List for Importers with further information.

- The entering company has researched and taken into account relevant legislation and regulatory considerations pertaining to their entry (assessing whether local laws and regulatory instruments may cause barriers for the business). In the context of Canada, it is important for entering companies to understand the impact of relevant legislation and regulation at the federal, provincial and municipal levels. Other factors to consider are potential interprovincial trade barriers that may exist. For the latter, entering companies should consult Canada’s Agreement on Internal Trade86.

- The entering company has identified and/or approached relevant local partners; these can include partnerships to aid in marketing, partnerships for manufacturing and/or product development, and others. In some cases, partnerships with local businesses may expand into joint ventures87. In this instance, the entering company may choose to work with a company in the host country by creating a third company to do so. An example of this is the Sony Ericsson joint venture, which allowed Sony to expand its share of the cellphone market, while Ericsson benefited by leveraging Sony’s then advanced mobile phone technology88. It is important to note that in Canada, the term ‘joint venture’ is not associated with a specific legal meaning, and therefore joint ventures tend to be regulated on a case-by-case basis89.

In addition to the steps noted above, it is important for entering companies to understand which resources are available to support both the entry process and their activities once they are established in the host country. While not intended to be an inclusive list, the following are examples of important resources that EU companies may use to support their entry into Canada.

Invest in Canada. In March 2018, the Minister of International Trade launched Invest in Canada90, a new federal organisation dedicated to attracting global investment and simplifying the process for global businesses to invest in Canada. Invest in Canada brings together all levels of government and private sector partners to provide a ‘one-stop service’ to global investors. Invest in Canada works with global companies in areas identified in the government’s economic growth strategy: advanced manufacturing, agri-food, clean technology, digital technology, health sciences and biosciences, and clean resources. Approximately 1.9 million Canadians are employed by foreign-controlled multinational enterprises in Canada: that is almost 12 % of Canadian workers, or one in eight Canadian jobs91.

Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada (ISED). ISED provides resources on several topics that can facilitate EU businesses to start or expand operations in Canada. ISED provides resources on a long list of business issues: taxes, permits and regulations, IP, business support and how to sell to the government, grants, loans, private and public sector financing, permits, licences and regulations (including broadcasting, distribution and spectrum licences, telecommunications standards and certifications), scientific research, funding, datasets, innovation support, facilities and educational resources, IP and copyright, funding, collaboration, and commercialisation and licensing resources92.

Horizon Europe. EU companies and researchers interested in public funding possibilities can learn more on the collaborative research and innovation projects offered by the Horizon Europe programme of the European Commission93, as well as international research and collaboration opportunities offered by the Canadian Government94.

Canada’s Regional Development Agencies95. The six agencies work closely with businesses and innovators in their regions to foster the right environment for business growth and entrepreneurship. The goal is to create ideal conditions for the development of strong, dynamic and inclusive regional economies throughout the country. The agencies help businesses scale up in the following ways:

- delivering nationally coordinated programs tailored to fit regional needs and circumstances;

- providing access to financial assistance;

- bringing together key players in their respective ecosystems;

- supporting community economic development;

- ensuring that regional growth strategies eliminate regional gaps and align with federal government objectives96.

(A) Canadian society and business culture

From its earliest history, the territory of Canada has been home to peoples of diverse ethnicities, religions and cultures. Before the arrival of French and English colonists hundreds of years ago, a wide variety of indigenous peoples lived across the territory. After Canada was formally established as a British colony, conflict between the values of English and French Canada gradually resulted in a political system based on compromise.

Canada’s current government and legal systems reflect its past as a British and French colony in North America and set it apart from most countries in Europe and the United States. Canada is a constitutional monarchy, and common law is used in all jurisdictions for criminal and civil matters outside of Quebec. However, the Province of Quebec (first settled by French people and still dominated by French speakers) has its own civil code, which applies to some areas of law such as family law. Various First Nations also have self-government, as stipulated through treaties.

Multiculturalism is a key part of Canadian identity and is enshrined in the Canadian constitution. Many vibrant, close-knit cultural communities exist in Canada. Official bilingualism is a key part of Canada’s multicultural identity. English is the native language of roughly 60 % of Canadians, while Canada’s second largest province, Quebec, is dominated by French speakers. There are substantial numbers of French and English speakers in almost all provinces. Reflecting decades of international immigration, nearly one in five Canadians are native speakers of non-official languages.

Canada is one of the highest-trust societies in the world and scores high on a range of measures, including gender equality and quality of life. In previous ICTC research, attributes like high quality of life, economic and social stability and natural beauty were regarded as key Canadian attributes that can help attract investment.

Canada is one of the easiest countries in which to set up a business and has a unique business culture (although some variations are present, particularly between Quebec and English Canada). Canadian business culture is a bit slower-paced, relationship-based and conservative than in the United States or northern European countries. Canadian businesses are collaborative and relatively willing to collaborate and give advice on how to refine ideas.

‘Business culture in Canada is different from the Netherlands. It’s more difficult at first to sell in Canada…You really need to build a personal connection to do business in Canada. It’s not really like that in the Netherlands, and even less in the US. If you’re trying to sell to Dutch people or Americans, they are very linear, very blunt. If you’re offering something that they think is useful, you can close a deal in just a few weeks. If you haven’t got something, the relationship will just fizzle… In Canada, the relationship building is slow; it can sometimes take months, if not years.’

Remco Dolman,

Founder and CEO of Spotzi

(B) Canada’s economy and ict sector

Canada is the 10th largest economy in the world. It is larger than any individual EU Member State economy, except Germany, Italy and France. Compared to other developed countries, Canada is more dependent on natural resources: oil and gas, forestry and mining are major contributors to the Canadian economy. Canada’s economy is highly integrated with the US economy, particularly in sectors such as manufacturing. For this reason, business connections in Canada can often be leveraged effectively to reach US clients.

The Canadian ICT sector represents nearly 5 % of the total Canadian economy, a figure that has been growing consistently for over a decade. To date, the ICT sector has seen faster growth than many other sectors of the economy.

Canada’s ICT sector is also highly diversified, reflecting the varied needs of Canadian and international customers. ICT companies focus on all dimensions of the Canadian economy: media and entertainment, agriculture, resource extraction, clean energy, finance and other verticals. Although Canada’s domestic ICT sector is mostly composed of small businesses, large international companies – mostly from the United States and the EU – have a growing presence in Canada. In addition to CETA, Canada is also part of the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement (formerly NAFTA), allowing it free trade privileges with the United States and Mexico.

Although Canada is an extremely large country, its population is concentrated around urban centres, particularly the cities of Toronto, Montreal, Vancouver, Calgary, Ottawa and Edmonton.

(C) Education and the labour market

Canada has world-class ICT talent. Graduates of top universities, including the University of Toronto, Université de Montreal, McGill University, the University of British Columbia, the University of Alberta and the University of Waterloo can, however, be hired at more favourable rates than other tech hubs, such as Silicon Valley.

Canadian tech workers are also very diverse. Nearly 40 % of Canadian ICT workers were born outside of Canada97, and cities like Montreal, Calgary, Vancouver and Toronto are especially diverse in ICT talent. International students also make up a high share of attendees at Canadian universities.

(D) Research, startups and industry communities

Canada’s research output is high and the country is home to some of the top names in computer science, such as Yoshua Bengio and Geoffrey Hinton. The Canadian government provides strong support for research and development activities through tax credits at the federal (e.g. the Scientific Research and Experimental Development incentive) and provincial levels, which supports the growth of a vibrant startup ecosystem in Canada.

Yet, the Canadian ICT sector is tilted toward startups and medium-sized organisations. Canada has historically not been as effective as the United States in creating ‘unicorns’ (privately held startup companies with a value of over $ 1 billion USD), and Canadian startups often face challenges in scaling their operations. The Canadian government’s ‘Supercluster’ initiative was created, in part, to assist startups on their scale up and commercialisation journey.

|

|

You can find more information on the webinar ‘How to find business partners in Canada’ produced under the CETA Market Access Programme here. |

4.4. Market entry requirements

The process of opening a new business in Canada has several scenarios, depending on whether the activity is an expansion of business operations that already exist in the country or if it is a brand new business.

The Corporation98 is the most common form of legal business structure for foreign companies seeking to establish new business operations in Canada. The Canada Business Corporations Act99 is a complete legal framework regulating Canadian business corporations on the federal level. It provides various requirements for both residents and non-residents who wants to register a company in Canada. Corporations in Canada may be incorporated federally, under the act, or provincially under a similar provincial business corporations act100. Each province in Canada has its own website where a business can register101. Incorporation is achieved by the filing of articles of incorporation. After obtaining an article of incorporation, the next step is to get a federal business number and corporation income tax account from the Canada Revenue Agency. If planning to conduct business across other Canadian jurisdictions, the next step is to register as an extra-provincial or extra-territorial corporation.

The two most common ways for existing foreign corporations to expand their businesses to Canada are through the registration of a Canadian branch or the incorporation of a Canadian subsidiary, which is then managed from abroad. A branch office is an extension of the foreign company, which means that the non-Canadian corporation will be subject to liabilities incurred by the branch. This business form requires that the non-resident investor appoint a local agent for the service of court documents. Branches can be registered on the federal level or provincially.

Foreign companies often prefer a joint venture with a Canadian company by incorporating a subsidiary. According to Canadian legislation, the subsidiary is an independent company whose controlling or sole shareholder is another corporation. Joint ventures may be created by the establishment of a new business or by acquiring a partial interest in an existing Canadian business102. This business form also requires that the non-resident investor appoint a local agent to complete the company incorporation procedure in Canada.

There are many angles to consider when deciding whether to register a branch or incorporate a subsidiary. These include tax implications, the ability to raise capital, access to the special programmes available through the Canadian government, and the parent company’s level of exposure to liabilities.

In the case of registering a brand-new business, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada offers a programme to non-resident innovative entrepreneurs who are willing to immigrate to Canada to start the business. The Start-up Business Class programme is for individuals who provide active and ongoing management of the business from within Canada and under the condition that an essential part of the business’ operations is conducted in Canada103.

It is also possible to enter the Canadian market as an investor through the federal government’s Immigrant Investor Venture Capital Pilot Program for high-net-worth individuals (minimum net worth of CAD 10 million) interested in immigrating to Canada and opening a business104.

5. Challenges and barriers to doing business in Canada (regulatory and technical)

Regulatory barriers can be commonplace when starting businesses in a new jurisdiction and/or expanding one’s reach from outside of a home country. Understanding how to navigate the processes, policies and regulations of a new country is no easy task. It requires considerable research and collaboration with key organisations in the host country to facilitate the journey.

While ICTC’s research has not specifically uncovered any regulatory or technical barriers that are especially burdensome to EU companies seeking to expand to Canada, regulation differs depending on the region as well as the type of business that is being set up. Regulation in Canada takes place at the federal (national) as well as the provincial (regional) levels. It is important to understand that regulations applying in one region do not necessarily apply in another (i.e. regulations pertaining to ride-hailing services in Ontario are not the same as those in British Columbia, Nova Scotia or Alberta). Understanding specific regional regulations is recommended prior to expansion.

(A) Provincial regulation

Although ICTC research has found that regulation is not an explicit barrier for businesses seeking to start operations in Canada, the regulatory system is nevertheless not uniform. The federal government regulates on issues it considers of ‘national importance’. These include criminal law, national defence, banking, Aboriginal affairs, citizenship and immigration, and international trade105. These and a few other areas are considered to be within the jurisdiction of the federal government. Areas of more ‘local significance’ are regulated at the provincial level. These include healthcare, infrastructure (other than critical infrastructure), public education, housing and road regulations106. As a result, this relatively fragmented system of regulation requires that companies wishing to enter the Canadian market research not only federal regulations but also regional regulations.

It is important to consider provincial differences, due to their implications for technology companies. For example, ride-hailing companies (such as Uber or Lyft) are treated differently depending on the province that they are operating in. Until early 2020, ride-hailing services were not legally allowed in British Columbia107, and yet they have been operating in Ontario since 2014108. Similarly, sharing economy platforms – notably Airbnb – are treated differently among provinces. In Ontario, regulations were introduced to limit Airbnb and the degree to which short-term rentals were permitted109, while in British Columbia, recent regulations require Airbnb hosts to obtain a business licence and only rent out their principal residence110. In Manitoba, properties listed through services like Airbnb were initially considered exempt from the provincial sales tax, but recent bylaw proposals may see Winnipeg Airbnb rentals levied with a 5 % hotel tax, like hotels111.

Unionisation can also differ from province to province. Recently, the Ontario Labour Relations Board ruled that Foodora couriers are dependent contractors for labour relations purposes. This move entitles couriers to unionise, providing them the ability to exercise collective bargaining power under the Labour Relations Act112. While Foodora operates in many Canadian provinces, unionisation rights, in this case, apply only to Ontario workers. Similarly, in British Columbia, a media workers’ union recently filed an employment standards complaint about a Vancouver animation studio regarding overtime pay (typically employers are not required to pay overtime for ‘high technology professionals’ under the Employment Standards Regulation). In its decision, the British Columbia Employment Standards Branch ruled in favour of the workers, stating that they are entitled to overtime pay for their work on a film113.

Just as regional differences exist in the EU (different laws for different Member States), entering a regional Canadian market should be treated similarly as entering a new EU Member State. Since different regulations and policies apply to each provincial jurisdiction on issues not considered of national interest, completing thorough research on the region of interest is highly advisable.

(B) Regulation by type of technology

Despite some provincial fragmentation, regulation on technology often takes place at the national (federal) level. Important regulations – and sometimes lack of regulation – are notable in various areas related to the technology sector in Canada. The following provides a brief description of a sample of key technology areas and their regulation in Canada.

Telecommunications. Telecommunications is one of the most highly regulated sectors in Canada. According to the OECD’s Foreign Direct Investment Regulatory Restrictiveness Index, Canada has the most regulatory restrictions to foreign investment of any OECD country in this space. This has been an issue of contention for many years, even spurring a suggestion by the OECD in 2016 that Canada loosen its foreign restrictions on the telecommunication sector in order to increase competition and drive down the cost of services for Canadians114.

Data and AI. Unlike the general data protection regulation in the EU, Canada does not currently have any concrete regulation on the use of data and AI. Yet, in recent years – and especially after the development of the general data protection regulation – many have called for Canada to implement regulations to mitigate potential harm that can be caused by AI and increasing data collection and use. In early 2020, the Canadian Office of the Privacy Commissioner launched a formal consultation, seeking feedback from Canadians on 11 proposals for the appropriate regulation of AI115. In this consultation, changes to the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act were also proposed116. The act was implemented in the early 2000s, prior to the large-scale proliferation of the internet and data economy. While this is a positive step, a timeline for official regulation is unknown.

Autonomous vehicles. Unlike the EU, which has developed guidelines for connected and autonomous vehicles, or individual Member States like Germany, which has developed standards for automated systems117, there are no existing regulations, standards or guidelines for autonomous systems in Canada118. In 2018, Transport Canada – Canada’s federal transportation authority – published Canada’s Safety Framework for Automated and Connected Vehicles119. Although the document did provide an overall picture of existing standards for vehicles, it also highlighted the current lack of standards specific to automation features.

Open banking. Open banking (the practice of sharing financial information electronically, securely and only under conditions that customers approve of, with the aim of promoting the development of new apps and services) is an accepted practice in many jurisdictions around the world, including the EU. Canada does not currently have an accepted framework for open banking. In 2018, the Canadian Department of Finance delivered a consultation paper120 on the topic, but there has not been significant movement on the topic. In early 2020, the Canadian Finance Minister announced a second phase of open banking review121.

(C) CETA

There are no CETA-borne barriers for EU businesses that wish do business in Canada (i.e. no provisions that specifically prevent or deter investment or business establishment by EU companies in Canada). In this and other research, ICTC has consulted with numerous EU companies that have started operations in Canada. Those who have leveraged CETA – for example to access the Canadian procurement market – found it relatively easy to do. However, the general conclusion from this and previous ICTC research suggests that EU companies have a general lack of knowledge about CETA. Many are unaware of its provisions and what they offer and/or are unaware of how to leverage the agreement.

(D) Other challenges

While regulatory or technical challenges were not perceived to be extraordinary in Canada compared to other jurisdictions, some challenges exist in relation to starting a business in Canada. These challenges primarily include differences in business culture, the relatively small size of the Canadian economy, the geographic vastness of the country and the high cost of living in the most attractive cities for business.

Table 4. Other challenges to doing business in Canada

|

A different business culture |

In general, Canadian business culture is regarded as more ‘conservative’ and, generally, more ‘risk-averse’. Relationships need to be built, which can take a significant amount of time. While Canada creates new businesses (startups) at a rate comparable to other competing countries, scaling up businesses continues to be a stumbling point. To date, Canada has not been overly successful in scaling up startups and creating significant success stories (Unicorns). Canada has been successful in sourcing growing amounts of FDI and venture capital. However, local investment has been slow. A recent report by the University of Toronto found that although venture capital is sufficient in Canada – notably for Series A funding (the first significant round of venture capital financing) – much of the venture capital investment in leading Canadian ICT companies came from the United States122. The companies with US venture capital backing raised more money than those receiving Canadian financing and were better positioned to become Unicorns123. New businesses to the Canadian market are not only advised to demonstrate their credibility but also their staying power (how likely it is that the new company will stay in Canada and help grow the Canadian ecosystem). |

|

A small economy in a large country |

Although Canada is among the largest economies in the world, it is still a small country with one-tenth the population of the United States. In short, there are only so many potential customers in Canada, with varying levels of regional digitisation and demand for ICT products and services. Canada is geographically large with vast distances between major cities, especially by EU standards. For example, while a flight from the nation’s capital (Ottawa) to Toronto is only 1 hour, driving would take approximately 6 hours. As a result, it may be more difficult (at least logistically) to expand operations across Canada and/or engage with key business leaders in other provinces on a face-to-face basis. |

|

High cost of living in key Canadian cities |

Some EU business leaders find the high cost of living in certain Canadian cities to be a barrier to business. Particularly, Toronto and Vancouver are highlighted as the most problematic, as the cost of living exceeds many jurisdictions in Europe. For example, the average cost of renting a 1-bedroom apartment in the Vancouver city centre is currently around EUR 1 319.70/month (CAD 2 000/month) and EUR 1 451.66 EUR/month (CAD 2 200/month) in Toronto124. Although prices have decreased nominally due to the COVID-19 pandemic, as of early 2020, the average cost of a detached house in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA) was over CAD 900 000125 and over CAD 1 000 000 in Metro Vancouver126. Other Canadian jurisdictions like Montreal, Ottawa, Calgary, Edmonton and Winnipeg are considerably less expensive. |

6. Tips for EU ICT companies establishing a business in Canada

6.1. Before starting operations

In researching the Canadian market (and perhaps the US market at the same time), EU companies considering expansion into Canada would do well to hire a business consultant or approach Canadian government agencies for advice. Key partners can be accessed through national organisations like Global Affairs or Invest in Canada or via regional organisations that promote transatlantic operations. Please see Annex II for a list of such resources.

Once plans are developed to set up a physical office in Canada, it is advisable to perform some additional research on the likely location of potential clients. Keep in mind the substantial regional differences in the Canadian economy and the significant distances.

6.2. Once in Canada

Typically, the same business skills developed in the EU will apply in Canada. While previous successes in Europe are important to building your brand in Canada, establishing local connections and partnerships in Canada is key.

Moreover, it is advisable to have at least one major decision-maker with ‘boots on the ground’ (physical presence) in Canada. This individual will be essential to fostering relationships, understanding Canadian business culture and forging the connections needed to scale. It becomes critical to invest time into making personal connections. Business relationships typically take longer to form in Canada than in the United States, but Canadians are very collaborative, and partnering with key organisations can help refine products for the Canadian market. Many Canadian cities host various industry events and meetup groups to facilitate these interconnections. Once products are refined to suit the needs of the Canadian market, further expansion to the United States becomes easier.

DOs

- Research current Canadian regulations or legislation across specific industries. For example, industries such as aviation and telecommunications are highly restricted to foreign investment due to their classification as areas of national interest. Businesses in these sectors must do their due diligence to understand how national legislation (irrespective of, or in combination with CETA) will impact their ability to enter and operate in Canada.

- Research provincial legislative and policy differences. Legislation pertaining to the ICT sector and the digital economy can differ from province to province. For example, as of 2021, businesses (both domestic and foreign) that develop IP in Quebec will be eligible for favourable tax treatment. This legislation is unique to Quebec and will not apply to businesses in other provinces.

- Explore national and regional organisations that can help to set up operations. Prime examples of such organisations are Invest in Canada and Global Affairs (at the national level), and provincial economic development organisations like FedDev in Ontario or ACOA for Atlantic Canada. Cities also tend to have their own economic development agencies, with part of their mandate being to liaise with foreign businesses and explore investment opportunities. Examples of such organisations at the city level include the Vancouver Economic Commission, Calgary Economic Development, the Halifax Partnership and Toronto Global.

- Explore beneficial tax credits or initiatives that may exist in certain provinces. For example, businesses in the creative technology space (video games, animation companies, etc.) may benefit from the Multimedia Titles Tax Credit in Quebec, which allows both domestic and foreign businesses to recover up to 37.5 % of eligible labour expenditures. Although similar tax credits exist in Ontario and British Columbia, the Multimedia Titles Tax Credit is considered the most robust credit of this nature in Canada.

- Research trade relationships and interprovincial trade agreements. Although efforts have been initiated over the years to eliminate or reduce trade barriers among provinces (from 1995, when the Agreement on Internal Trade was developed), some barriers still exist, particularly among provinces that, largely due to their location, had been somewhat removed from interprovincial trade in the past. This reality is by no means crippling but can nonetheless impact business operations.

- Have at least one major decision-maker that is primarily based in Canada.

- Find Canadian partners (public or private) that share your vision and can help build key relationships in the Canadian marketplace.

- Learn about the characteristics of Canadian business culture and standard operating procedures. Note that business culture can also differ from province to province and even from city to city. For example, the business culture in Toronto may be seen to be more closely aligned with that of New York versus Halifax. Similarly, the business culture in Vancouver may be seen to be more similar to that of Seattle or San Francisco, versus Toronto.

- Attend industry events, meetup groups, etc. to help build your network at the industry and labour market levels. Such events can prove useful to forging business connections, meeting policymakers and connecting with local skilled talent.

DON'Ts

- Assume that CETA means that all sectors in the digital economy are equally accessible.

- Expect that policies or legislation that apply in one province will automatically apply in another. Provinces can have varying and sometimes unique economic or sectoral priorities that shape policy directions.

- Expect that there is any one go-to organisation or institution (a ‘one-stop shop’) responsible for liaising or working with businesses that wish to set up operations in Canada.

- Expect tax credits that apply in one province to apply in another, or that all provinces have tax credits for the same business activities (for example, some provinces do not have a multimedia tax credit).

- Expect that the concept of free trade is one that is practiced evenly among Canadian provinces.

- Run operations remotely, with only a staff presence in Canada.

- Assume that due to similar foundational values and norms, business culture in Canada is necessarily similar to European (and host country) culture.

- Assume that business and talent connections need to be built exclusively using formal mechanisms like meetings or interviews.

7. Case studies of successful eu businesses in the Canadian ICT sector