Maritime transport

Globally, approximately 13 billion tonnes of traded goods were transported by sea in 2023, a 2.4%-increase from the previous year.

However, the EU-27 picture is different, as the gross weight of goods handled in ports declined by 3.9% in 2023, dropping from 3.5 billion tonnes in 2022 to 3.4 billion tonnes. After experiencing growth in the first three quarters of 2022 compared with the previous year, a decline was observed from the final quarter of 2022 through the last quarter of 2023. The decrease in goods handled is primarily due to restrictions on goods transport to and from Russia, owing to its military aggression against Ukraine.

When focusing on the Member State level, the year-on-year (2023 over 2022) change in gross weight of goods handled is very heterogeneous, spanning from -31% in Estonia (23 million tonnes) to +47.5% in Malta (7.2 million tonnes). The Netherlands recorded the largest gross weight of goods handled at 545 million tonnes (-7.6% from 2022), followed by Italy with 500 million (-1.7%) and Spain with 471 million (-3.7%).

Liquid bulk goods (e.g. oil) represented roughly 37.9% of the total goods handled in the EU (1.26 billion tonnes), followed by large containers with 22.7% (757 million tonnes) and dry bulk goods (e.g. grain) with 21.6% (720 million tonnes).

Short sea shipping (SSS) is defined as the maritime transport of goods between ports in the EU (sometimes also including candidate countries and European Free Trade Association countries) on the one hand, and ports situated in geographical Europe, on the Mediterranean Sea and Black Sea, on the other hand. In 2023, 1.6 billion tonnes of goods were transported by SSS, 5.4% less than in the previous year. The busiest region for SSS was the Mediterranean Sea, where roughly 39% of the goods were transported in terms of gross weight (628 million tonnes), followed by the North Sea (29% and 472 million tonnes) and the Baltic Sea (18% and 285 million tonnes).

In 2023, 386 million passengers (excluding cruise passengers) embarked and disembarked in all EU ports, a 6.8%-increase compared with 2022. Cruise passengers were roughly 16 million, almost 34% more than the previous year, surpassing pre-pandemic levels for the first time (15 million in 2019).

The sector Maritime transport includes the following sub-sectors:

- Passenger transport: sea and coastal passenger water transport and inland passenger water transport;

- Freight transport: sea and coastal freight water transport and inland freight water transport;

- Services for transport: renting and leasing of water transport equipment.

Size of the EU Maritime transport sector

The sector generated a gross value added (GVA) of € 61.8 billion in 2022, a 39%-increase compared with 2021. Gross profit, at € 43.9 billion, increased by 56% on the previous year. The turnover reported for 2022 was € 228 billion, a 29% increase on the previous year.

Estimates for 2023 suggest a stable performance, with GVA, turnover and gross profit increasing less than 1%.

In 2022, almost 392 800 people were directly employed in the sector, 4% more than in 2021. The annual average wage was estimated at € 45 700, up 6% compared with 2021.

The estimate for the people employed in 2023 is 407 400, while the estimated average remuneration is € 44 800.

Figure 35 Size of the EU Maritime transport sector, 2009-2023. Turnover, GVA ad gross operating surplus in € billion, people employed and average wage (€ thousand)

NB: Turnover and people employed in 2023 were estimated based on Eurostat’s preliminary data; GVA, gross operating surplus and average remuneration were estimated assuming they follow the same trend as turnover.

Source: Authors’ own calculations based on Eurostat (SBS) data.

Results by sub-sectors and Member States

Germany has the highest employment within the Maritime transport, accounting for 33% of jobs in the sector, followed by Italy (17%) and France (10%). Germany generates 52% of the Member States’ GVA in the sector, followed by Denmark (13%) and the Netherlands (10%).

Figure 36 Share of employment and GVA in EU Maritime transport sector, 2022

Source: Authors’ own calculations based on Eurostat (SBS) data.

In 2022, about 50% of jobs (197 700) were within the services for transport subsector, while passenger transport (102 700) and freight transport (92 500) employed 26% and 24% of people, respectively.

Freight transport generated about 65% of the sector’s GVA (€ 40.6 billion), followed by services, with 25% (€ 15.3 billion), and then passenger transport, with 10% (€ 6 billion).

Connectivity of EU shipping network

Based on the Liner Shipping Connectivity Index, which indicates a country’s integration into global liner shipping networks, the most-connected European economies in the last quarter of 2024 were Spain (up 3.4% from the last quarter 2023 2023), the Netherlands (-5.4%) and Belgium (-1%).

The most connected EU ports in the last quarter of 2024 were Rotterdam (Netherlands, -6.8% compared with the same quarter in 2023), Antwerp (Belgium, -0.1%) and Hamburg (Germany, -0.5%), according to the Port Liner Shipping Connectivity Index, which measures a port’s integration into global liner shipping networks.

Trends and drivers

The EU Maritime transport sector is undergoing significant transformation driven by evolving geopolitical dynamics, digitalisation, the energy transition and increasing climate risks.

Route changes due to geopolitical factors and climate change: over the past two decades, the Maritime transport sector has undergone a significant structural transformation. The combination of climate change and geopolitical tensions represents one of the most significant risks to global maritime trade in decades.

Maritime chokepoints, which serve as essential arteries for global commerce, are particularly vulnerable. With few viable alternatives, disruptions at these strategic passages can have far-reaching consequences, affecting food security, energy supplies, and economic stability worldwide. For example, the Turkish Straits faced disruptions in 2023 and 2024 due to geopolitical tensions, rising maritime traffic, environmental concerns, and infrastructure-related challenges. Meanwhile, climate change is exerting pressure on another critical trade corridor – the Panama Canal. A severe drought has led the Panama Canal Authority to impose transit restrictions to conserve water, significantly reducing vessel traffic. In May 2024, the total number of transits declined by 19.2% compared with May 2023 and by 24.3% compared with May 2022,. Adding to these challenges, since mid-November 2023, escalating security risks in the Red Sea have led major shipping companies to suspend transits through the Suez Canal. In response, a significant share of ships on the Asia–Europe trade route has diverted around the Cape of Good Hope. This shift has heightened costs for Europe, which remains heavily reliant on imports from Asia.

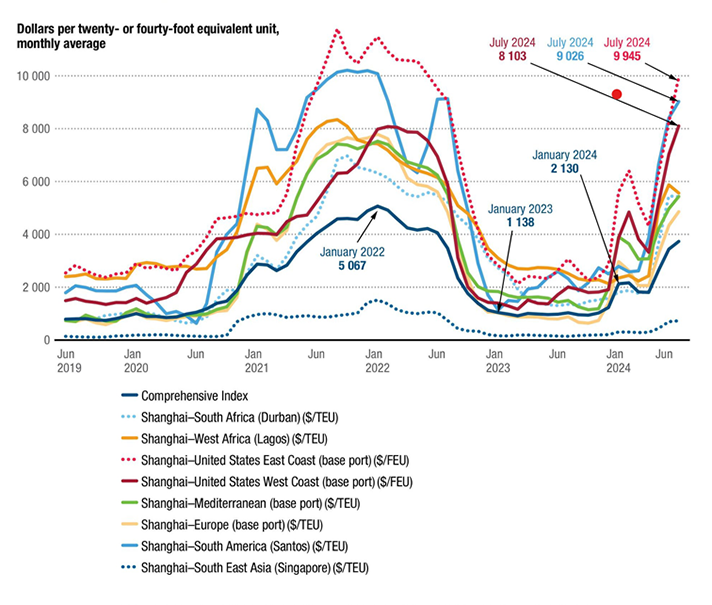

Spot freight rates on the Asia–Europe corridor, the EU’s main import route, have risen sharply since late 2023 (see Figure 37). Average costs per container (20-foot equivalent units) have approached levels seen during the peak of the pandemic. On the Europe–America corridor, freight rates have also increased considerably, reflecting accumulated stress across European and global logistics chains.

Figure 37 Spot rates for the Shanghai Containerised Freight Index

NB: FEU, 40-foot equivalent unit; TEU, 20-foot equivalent unit.

Source: Calculations of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development based on data from Clarksons Research’s Shipping Intelligence Network.

Addressing these vulnerabilities requires urgent action to strengthen the resilience of global supply chains and ensure uninterrupted maritime trade. Diversifying shipping routes is crucial to reducing dependency on a limited number of critical passages, while greater cooperation among shippers, providers of logistics services, and ports can help optimise supply chain efficiency. At the same time, leveraging technology, data, and predictive analytics will improve demand forecasting, enhance early warning systems, and enable better capacity management at chokepoints, ultimately mitigating the risks posed by geopolitical instability and climate change.

Digitalisation

One main driver of the digital transformation is artificial intelligence (AI). AI can for example optimise routes based on historical data and current traffic conditions, thereby minimising costs and reducing delivery times. In addition, it can be employed in forecasting demand, optimising inventory levels and reducing stock-outs, and in predicting when equipment may need maintenance, minimising downtime and extending the lifespan of assets. Some European companies, such as Maersk, are already employing AI to facilitate certain processes.

Another digital technology that could have an impact on the maritime transport industry is blockchain. Blockchain-based digitalisation tools (e.g. CargoX, created by a Slovenian company) can improve supply chain transparency and cargo tracking, execute smart contracts, increase cybersecurity and prevent fraud.

Digitalisation is also driving advancements in the area of autonomous ships. These advancements range from steering and navigational assistance to full automation of navigation, potentially reducing operational costs, improving working conditions, saving fuel by optimising routes, and reducing human errors and accidents. The EU-funded Autoship project showcased how cutting-edge innovation on two vessels could support navigation as well as mooring and docking.

Digitalisation also plays a fundamental role in emissions monitoring. In this context, digitalisation has advanced substantially, pushed by stricter and stricter EU regulations that promote a greener shipping industry, such as the EU emission trading system (ETS) and the FuelEU Maritime Regulation. The monitoring, reporting and verification (MRV) system, introduced in 2015, provides detailed fuel-based data on vessel-level CO₂ emissions. From 2025, MRV coverage will expand to include general cargo vessels and offshore ships between 400 and 5 000 gross tonnage (GT). The MRV is complemented by other emissions monitoring frameworks, including the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) GHG inventories and the Ship Traffic Emissions Assessment Model (STEAM). These systems use different methodologies: the MRV system tracks onboard fuel consumption per vessel, the UNFCCC applies the principle of territorial accounting, and STEAM uses ship activity data from the automatic identification system.

Despite growing operational and environmental demands, the digitalisation of European maritime logistics remains uneven and largely underdeveloped. According to the European Maritime Transport Environmental Report 2025, digital technologies are still treated as a secondary tool rather than an essential infrastructure component.

In this context, the Commission’s Digital Transport and Logistics Forum provides a platform for structural dialogue, the provision of technical expertise, and cooperation and coordination between the Commission, Member States and the transport and logistics sector, with the objective of developing and implementing digital interoperability and data exchange within the industry.

Decarbonisation

Maritime transport is facing increasing environmental scrutiny. In 2022, the industry accounted for 14.2% of transport-sector emissions in the EU. Its CO₂ emissions were on the rise – reaching 137.5 million tonnes, up 8.5% from the previous year. In addition, the expansion of the LNG fleet has been linked to increasing methane emission, and there has been a 10%-rise in NOx emissions over the past decade, with notable increases in the Atlantic and Arctic regions.

In response, the European Commission has initiated a profound regulatory transformation of the maritime sector, with Maritime transport now a key pillar of the European Green Deal and the fit for 55 legislative packages. The inclusion of shipping in the EU ETS starting in 2024 – shipping companies must purchase and surrender emission allowances for each tonne of CO2 or CO2 equivalent reported – and the enforcement of the FuelEU Maritime regulation – ships above 5 000 gross tonnes calling at EU ports must respect limits on GHG intensity, which will gradually increase until 2050 – from 2025 signal a turning point. In parallel, sulphur emission controls are tightening, with the designation of the Mediterranean Sea as a sulphur emission control area from May 2025. The development of supporting infrastructure is addressed through the Alternative Fuels Infrastructure Regulation, which requires European ports to be equipped with LNG bunkering infrastructure – for which the deadline was January 2025 – and to plan for the deployment of hydrogen, methanol, and ammonia refuelling infrastructure. Furthermore, the revised Renewable Energy Directive sets binding targets for the use of renewable fuels in the transport sector, including e-fuels and advanced biofuels. Finally, the ongoing revision of the Energy Taxation Directive seeks to eliminate existing tax exemptions for fossil fuels used in intra-EU maritime transport, aligning fiscal policy with EU climate objectives.

However, the effective adoption of clean technologies in maritime transport is still progressing slowly. In 2023, only 0.77% of the active fleet in Europe used alternative fuels, highlighting the gap between regulatory objectives and the actual transformation of the sector. This energy transition poses a significant challenge to the workforce: it is estimated that over 800 000 seafarers will require specific training in new technologies and alternative fuels by 2035.