Country Report

Malta

1. Key Indicators

Figure 1: Key indicators overview

| Malta | EU | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 2021 | 2011 | 2021 | ||||||

| EU-level-targets | 2030 target | ||||||||

| Participation in early childhood education (from age 3 to starting age of compulsory primary education) | ≥ 96% | 99.4%13 | 89.1%20 | 91.8%13 | 93.0%20 | ||||

| Low achieving eighth-graders in digital skills | < 15% | : | : | : | : | ||||

| Low achieving 15-year-olds in: | Reading | < 15% | 36.3%09 | 35.9%18 | 19.7%09 | 22.5%18 | |||

| Maths | < 15% | 33.7%09 | 30.2%18 | 22.7%09 | 22.9%18 | ||||

| Science | < 15% | 32.5%09 | 33.5%18 | 18.2%09 | 22.3%18 | ||||

| Early leavers from education and training (age 18-24) | < 9% | 18.8%b | 10.7%b | 13.2% | 9.7%b | ||||

| Exposure of VET graduates to work-based learning | ≥ 60% (2025) | : | 48.3% | : | 60.7% | ||||

| Tertiary educational attainment (age 25-34) | ≥ 45% | 26.2%b | 42.5%b | 33.0% | 41.2% | ||||

| Participation of adults in learning (age 25-64) | ≥ 47% (2025) | : | : | : | : | ||||

| Other contextual indicators | |||||||||

| Equity indicator (percentage points) | : | 25.418 | : | 19.30%18 | |||||

| Early leavers from education and training (age 18-24) | Native | 18.9%b | 9.4%b | 11.9% | 8.5%b | ||||

| EU-born | :b | :bu | 25.3% | 21.4%b | |||||

| Non EU-born | : | 21.1%bu | 31.4% | 21.6%b | |||||

| Upper secondary level attainment (age 20-24, ISCED 3-8) | 78.9%b | 88.7%b | 79.6% | 84.6%b | |||||

| Tertiary educational attainment (age 25-34) | Native | 25.4% | 40.7%b | 34.3% | 42.1%b | ||||

| EU-born | :u | 50.1%b | 28.8% | 40.7%b | |||||

| Non EU-born | 37.2% | 45.5%b | 23.4% | 34.7%b | |||||

| Education investment | Public expenditure on education as a percentage of GDP | 5.6% | 5.9%20 | 4.9% | 5.0%20 | ||||

| Public expenditure on education as a share of the total general government expenditure | 13.5% | 12.8%20 | 10.0% | 9.4%20 | |||||

Sources: Eurostat (UOE, LFS, COFOG); OECD (PISA). Further information can be found in Annex I and at Monitor Toolbox. Notes: The 2018 EU average on PISA reading performance does not include ES; the indicator used (ECE) refers to early-childhood education and care programmes which are considered by the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) to be ‘educational’ and therefore constitute the first level of education in education and training systems – ISCED level 0; the equity indicator shows the gap in the share of underachievement in reading, mathematics and science (combined) among 15-year-olds between the lowest and highest quarters of socio-economic status; b = break in time series, u = low reliability, : = not available, 09 = 2009, 13 = 2013, 18 = 2018, 20 = 2020.

Figure 2: Position in relation to strongest and weakest performers

2. A focus on early leaving from education and training

Early leaving from education and training (ELET) is a multifaceted issue and many factors can explain Malta’s situation. Although the rate is still above the EU average (10.7.0% vs 9.7% in 2021), it has decreased by 10.7 pps since 20101 with one of the highest percentage drop rates in the EU. Research shows that the interplay of a number of complex factors in the individual situation of each student contributes to the risk of early leaving from education and training. In the Maltese context, favourable labour market conditions in recent years for low-qualified people may have motivated young people to leave education early (Guio, et al. 2018, Ministry for Education and Employment, 2012). This may have been especially the case for students from a low socio-economic background, and boys, who tend to be more attracted by the labour market opportunities (Guio et al. 2018). In 2010, the ELET rate for boys was much higher than for girls (28.3% vs 14.1%). Since then, it has decreased more significantly for boys (-16.3 pps) than for girls (-4.8pps) also due to changes in the labour market. In the past, more low-skilled occupations filled by men were available in the Maltese labour market2 (Ministry for Education and Employment, 2012). At the same time, the high level of underachievement of Maltese 15-year-olds and the low level of student well-being (European Commission, 2021) coincides with the high Maltese ELET rate. International research confirms a higher risk of being an early school leaver in the case of high underachievement and low student well-being (Korhonen et al., 2014). An increasing proportion of foreign-born pupils (European Commission, 2021), who require additional help to catch up and to be integrated in school, may also explain high rates of early school leaving in recent years and the gap between Malta-born and foreign-born pupils. A high rate of absenteeism in the past may also have contributed to a higher incidence of ELET. Other causes may be found in school and class environments (Ministry for Education and Employment, 2012 and, 2017). Bullying is an issue which concerns all types of schools and students in Malta (European Commission, 2021) and is one of the reasons for dropping out of education (Ministry for Education and Employment, 2017). The provision of guidance in secondary schools tended to be biased towards the academic path in the past (Ministry for Education and Employment, 2012 and, 2017). This may also have negatively affected decisions on remaining in education and training by less engaged students. Further evidence-based research may help investigate national specificities of the phenomenon, facilitating more targeted actions to support children early on and to address gaps in current provision. The data warehouse project envisaged in the national recovery and resilience plan (European Commission, 2021), which will collect various data about students from the beginning to the end of their educational path, may help in this sense.

Malta has achieved significant improvements in decreasing its ELET rate since 2010. In recent years, several efforts have been made to tackle early leaving from education and training and further decrease the rate in the short- and medium-term. An early school leaving unit within the Ministry for Education has been set up to ensure a more coordinated approach to the ELET challenge. Malta has strengthened vocational education and training as it can provide pupils with an alternative to the more academically oriented, traditional school programmes. Vocational subjects have being offered to secondary students since 2011 and, as of 2019, through the ‘MyJourney’ reform, secondary school students are being offered applied learning subjects as part of an alternative learning programme. In the previous programming period 2014-2020, with the support of European Structural and Investment Funds, vocational education and training infrastructure and courses in compulsory and post-secondary education were redesigned to make them more attractive and relevant to the labour market. Psychosocial services for students and their parents and teacher trainings on ELET and social inclusion have been strengthened throughout the past decade and national evidence shows positive trends on bullying for the past two years. Several second-chance education programmes have been developed for those who disengaged from education or who did not successfully complete the secondary education certificate (e.g. revision classes, foundation programmes, GEM16+3, and targeted measures such as Embark for Life and Pathways). The free childcare scheme launched in 2014 for all parents and guardians working or studying full-time is another example of a prevention measure at system level to reduce the risk of early leaving from education and training.

Figure 3: Early leavers from education and training, 2010 and 2021 (%)

Further actions are planned to continue tackling ELET; implementing a whole-school approach may be key to succeeding. The text of the national strategy on early leaving from education and training presented for public consultation in 2021 endorses whole-school approaches and targeted prevention measures directed at at-risk pupils. This may help to ensure a better coordination of the numerous ongoing initiatives. The government aims at addressing causes of absenteeism, which is often regarded as a first sign of disengagement and leaving education early. According to Eivers (2020), data on attendance are not systematically used to identify general patterns of absence as the issue is mainly treated as an individual problem and not as a structural problem. Data are not sufficiently used to inform whole-school responses that engage the entire school community to reduce absenteeism. The government plans to strengthen communication between teachers and parents to ease children’s transition to middle and secondary schools and build trust and mutual understanding, which stands at the core of the whole-school approach (European Commission, 2015).There is also the intention to strengthen vocational programmes such as the Alternative Learning Programme, which is a pull-out intervention measure for students who do not plan to sit secondary education certificate examinations or who are low academic achievers and/or habitual absentees. The government also aims at extending the free childcare scheme to all parents, regardless of whether they work or not (Abela, 2022). This may favour access of disadvantaged children who are most likely to benefit from participation in childcare. Effects on school engagement and completion rates would take a long time to appear but, provided that early childhood education and care provision is of high quality, are likely to be significant.

3. Early childhood education and care

Participation in early childhood education (ECEC) continues to decrease for children older than 3 years. The proportion of children over 3 in early childhood education stood at 89.1% in 2020, compared with an EU average of 93%. The rate has decreased by 7.8 pps since 2015, the highest decrease in the EU. In 2020, the proportion of children below 3 in formal childcare also decreased dramatically, by 8.6 percentage points4 since 2019. This latter result may be explained by the COVID-19 pandemic and the health restrictions in place in childcare centres; these may have affected provision and participation.

Efforts to ensure high quality ECEC are underway. In the 2022/2023 school year, after being put on hold due to COVID-19 pandemic, reform of the learning outcomes framework will continue. As part of this, teacher training on the new curriculum for the early years also resumed. The new national standards for private and public childcare centres for children below 3 years have been in place since October 2021. An effective implementation of the new policy framework for ECEC, published in 2021, envisages evidence-based monitoring and evaluation. This may help to improve quality across the sector and plan more effective investments. The government envisages to employ teaching assistants also in childcare centres; they will help identify and address learning difficulties as early as possible. While welcomed in principle, research has pointed to the need to well-prepare and evaluate the deployment of teaching assistants to achieve results. (Higgins, 2014; Sharma and Salend, 2016; Sharples, Webster and Blatchford, 2015). Evaluations of the role of learning support educators in Malta’s schools and their impact on student outcomes may also help to better understand what to plan at the level of ECEC. The Institute for Education will offer ECEC staff more opportunities to continue their professional learning to get a higher qualification on a part-time basis.

4. School education

Implementation of the 2017 learning outcomes framework has started at primary level; the government nevertheless plans to revise the competence-based curriculum. Implementation at higher education level started in 2018/2019 with the development of new syllabi (European Commission, 2019). The curriculum reform was intended to lead to more school autonomy and a more learner-centred approach (Caruana, 2019). The government (Abela, 2022) plans to update the curriculum with the objective of reacting to the need of equipping students with skills more relevant to the labour market. Competence-based curricula can help improve student achievements (European Commission, 2022d), if accompanied by appropriate preparation of schools and teachers. Competence-based teaching requires schools to adopt new approaches, such as cross-curricular planning and competence-based student assessments that capture students’ abilities to address complex problems. The shift to competence involves changes in pedagogical approaches to teaching, learning and assessment (European Commission, 2022e). Therefore, curricular reforms should be carefully designed to leave time for teachers and schools to prepare for further changes. Buy-in, and the active engagement of teachers and schools as enactors and mediators of the reform, are key factors for the success.

Malta aims to focus more on the development of creativity and critical thinking and to give more weight to coding as a key topic at primary and secondary level. The subject ICT C3 was introduced at lower secondary level in 2018/2019, and in 2022/2023 at grade 11 in upper secondary level. Currently, it is a separate compulsory subject and includes coding, digital ethics, blockchain and digital safety among others. (European Commission/ EACEA / Eurydice, 2022). Making coding a key subject at all levels will require ICT teachers with advanced digital competence and appropriate pedagogical skills. Teacher shortages may arise as the demand for ICT graduates is already high in the Maltese labour market (European Commission, 2022c) and salaries and careers in the private sector tend to be much more attractive.

Making the teaching profession more attractive is one of the government’s aims. Research shows a positive link between teacher quality and student performance (Hanushek, Schwerdt, Wiederhold et al., 2015; Chetty, Friedman & Rockoff, 2014). In the Maltese context, where the proportion of 15-year-olds underachieving in all three PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment) domains combined is among the highest in the EU (22.6% vs 13.2%), attracting effective teachers and ensuring high teaching quality is key to addressing the basic skills challenge. Since 2014/2015, teachers’ starting salaries have increased by about 10% as the result of collective bargaining (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2020) and further increases are planned in the next 5 years. This may explain the increase by 10.4 pps in the share of new entrants in education fields at bachelor level between 2015 and 2020. Although starting salaries are important in attracting new teachers, a significant salary progression may also contribute to improving the attractiveness of the teaching profession, both for serving teachers and for potential candidates. However, salary progression shows only modest salary increases over a short time period (European Commission, 2019 and European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2021b). Further financial incentives are also considered for the induction phase during which novice teachers will start getting a salary. While this shows a high commitment to improving the attractiveness of the profession, teacher working conditions also greatly affect the attractiveness of the profession and the quality of teaching in classes. The 2018 Teaching and Learning International Survey highlights that a high proportion of teachers consider that they do not receive sufficient incentives in continuing professional development, (European Commission, 2019). This may be due to the fact that participation in continuing professional development is not required for career progression and schools are not required to develop a CPD planning (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2021a), which may balance individual and organisational learning needs and help to better target teacher and student needs.

Malta plans to introduce targeted additional funding for schools with disadvantaged students. Currently, the allocation of funding is student-focused: Through the Scheme 9, students from disadvantaged background are provided with basic educational necessities such as uniforms and have access to extracurricular activities. The objective for the future is to provide additional support to schools with the largest number of pupils coming from a disadvantaged background. Such support will include a larger allocation of funds and more resources to carry out targeted programmes (Abela, 2022). Currently, Malta is one of the few EU Member States in which such resources are not allocated (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2020a). A more systematic and systemic collection of data on student socio-economic backgrounds at school and student level may help the Ministry for Education to be better able to evaluate how funds – and programmes - might be best targeted (i.e. at school or student level) to support students from a disadvantaged background, (European Commission, 2020).

Box 1: Investing in learning environments

Malta has been heavily investing in its education infrastructure through EU funds and the national budget. Although causal evidence is still limited, recent literature suggests that good architectural and educational design may lead to improved learning outcomes for students by influencing teacher and student behaviour, morale and practices. The share of public expenditure on education spent on buildings and fixed assets increased by 62% between 2015 and 2020, and was 12.8% of total education expenditure in 2020 (EU: 7.2%). Further investments are planned for the coming years at all education levels (Abela, 2022). They will cover schools, science laboratories, sports facilities, libraries and facilities for cultural activities. These investments are partly due to the dramatic increase in the student population seen in recent years5. However, they also respond to other needs: first, making public infrastructure greener and more energy efficient as also envisaged in the national recovery and resilience plan such as the near-carbon neutral primary school in Msida as well as the renovation of Għaxaq and Nadur Primary Schools; improving attractiveness of vocational education (European Commission, 2021); making learning spaces more inclusive as in the case of the new multisensory rooms for students with special needs (European Commission, 2021) included in the national recovery and resilience plan; and adapting educational buildings to new technologies and use of ICT for teaching (European Commission, 2022b). Data on school infrastructure is centrally collected by the Foundation for Tomorrow’s Schools. This may inform the annual assessment of investment gaps, which is usually carried out through stakeholder consultations (European Commission, 2022b).

5. Vocational education and training and adult learning

Despite recent investments in infrastructure and quality, the take-up of vocational education and training (VET) at upper secondary level is stagnant and below the EU average. Despite a high employment rate of recent VET graduates (89.0% vs 75.7% at EU level in 2020), the share of learners enrolled in 2020 in upper secondary VET in Malta remained at 27.6%, from 27.7% in 2019 and 28.5% in 2018, still well below the EU average (48.7% in 2020). Malta’s main provider for vocational education and training, the Malta College of Arts, Science & Technology (MCAST), adopted in 2021 a new strategic plan covering the period 2022-2027. It includes several targets such as providing work-based training to all students and contributing to a 10% increase in adult-learning participation by 2027. The share of VET graduates benefiting from exposure to work-based learning during their vocational education and training was 48.3% in 2021, below the EU average (60.7%). MCAST also inaugurated a new resource centre hosting an applied research and innovation centre, a library, classrooms and an IT lab, co-funded by the European Regional Development Fund. The government plans to make the location available to voluntary organisations for educational and social activities.

Malta has one of the highest shares of low-skilled adults whose participation in learning remains low despite their greater needs. The proportion of people aged between 15 and 64 with a low level of education in 2021, while decreasing, stood at 36.1% compared with 24.6% for the EU.. While participation in learning for all adults is above the EU average (13.9% vs 10.8%), the rate for the low-skilled remains low (3.8%) in 2021, despite higher needs for upskilling and reskilling. To improve take-up, the Directorate for Research, Lifelong Learning and Employability has further developed guidance provisions in adult-learning centres and launched a basic skills assessment tool, the Skills Checker, developed as part of the Erasmus project Check In, Take Off (CITO). In 2022, the ‘e-college’, a digital learning platform for adults, is expected to be launched as part of Malta’s national recovery and resilience plan. It aims to attract 4 800 learners before the end of 2024.

Malta is in the process of adopting key policy documents on adult learning. Following a consultation process in 2021, Malta plans to adopt in 2022 the National Strategy for Lifelong Learning 2020-2030, focusing on opportunities for low-skilled adults, inclusion, enhanced quality of learning, guidance and digital education. The Maltese Upskilling Pathways working group is also in the process of drafting of a basic skills framework that is a part of the national recovery and resilience plan, which is expected to enhance the quality of the learning offer. In October 2021, Malta published a renewed employment policy that includes relevant recommendations for the upskilling and reskilling of workers, such as launching a skills census, revamping the Skills Policy Council, developing a transversal skill set certification and an industry skills framework for all economic sectors. The policy document also calls for greater recognition of workplace learning, building capacity for recognition of prior learning, and improved career guidance. Malta has set a 2030 target for 57.6% of adults to be in learning every year, a huge increase from the 32.8% rate in 2016.

Box 2: Training for employment

Co-financed by the European Social Fund 2014-2020, the ‘training for employment’ project covers several initiatives - the work placement scheme, the work exposure scheme, the traineeship scheme, the developing skills scheme, a research study to define arduous and hazardous jobs in Malta, and the development of an occupational handbook - to facilitate access to employment through the development of skills of the working age population. Through the work placement, work exposure and traineeship schemes, employers, in partnership with Jobsplus - Malta’s public employment service - are provided with the opportunity to train their prospective future employees. For all three schemes, participants are paid a training allowance calculated on the national minimum wage, payable by Jobsplus. All three schemes are available for both registered unemployed people and inactive jobseekers. Under the ‘training for employment’ project, from January 2016 until the end of December 2021, 3 128 trainees benefited from the work exposure scheme, 154 trainees benefited from the work placement scheme, and 651 trainees from the traineeship scheme. In addition, 4 101 individuals were eligible for funding under the ‘developing skills’ scheme, from March 2017 to end 2021. The ‘training for employment’ project will be extended until 2023.

More information available at: https://jobsplus.gov.mt/

6. Higher education

Better targeted funding may help improve the responsiveness of the higher education system. The proportion of 25-34-year-olds with tertiary education increased by 2.4 pps over the previous year to 42.5% in 2021. The attainment rate among the EU-born population from outside Malta (50.1%) surpasses that of the Maltese population (40.7%) and it is also relatively high among the non-EU-born (45.5%). The employment rate of people with tertiary qualification remained6 high (94.7%) in 2021 and above the EU average (84.9%) despite the COVID-19 outbreak. It still continues to be a key factor in attracting qualified people to Malta (Central Bank of Malta, 2021). In order to incentivise students to continue their studies, the government aims at strengthening existing scholarships and the tax credits programme for students at master’s and doctoral level. While this measure may help increase the total number of people with more specialised and higher competence levels, it may need to be better targeted to improve the responsiveness of tertiary education to labour market needs more effectively, and to ensure that high investments yield improved outcomes. Between 2016 and 2020, the number of new entrants already increased from 1 340 to 2 401 at master’s level and from 1 to 33 at doctoral level. The increase mainly concerned services and education fields: the number of new entrants has increased nine fold and four fold respectively, while entrants to ICT and health fields have remained practically the same despite the high demand of ICT specialists and future needs (European Commission, 2022c). Moreover, entrants to ICT fields only represented 2.7% of total new entrants in 2020, while it was 4.2% in 2016 (Figure 4). However, the share of firms reporting hard-to-fill vacancies for jobs requiring ICT specialist skills is above the EU average - 66.1% vs 55.4% in 2020 (European Commission, 2022c).

Figure 4: New entrants at ISCED 7 level, 2016 and 2020 (%)

Further improvement in student mobility is one of the objectives of the government. Learning mobility has been found to be associated with benefits such as future mobility, higher earnings and lower unemployment. International student mobility could also have benefits at country level. Mobile students can contribute to knowledge absorption, technology upgrading and capacity building, not only in the host country but also in their home country if they return home after studies or maintain strong linkages with people at home (European Commission, 2018). In 2020, the share of outward mobile students7 was one of the highest in the EU, standing at 7.5% compared with 4.2% at EU level. The full portability of grants from which Maltese students can benefit lightens the costs of mobility. Mobility is incorporated in the strategic plan of the University of Malta and increasing student mobility is one of the targets to be achieved by 2027 in the MCAST Strategic Plan 2022-2027. Further increases may be achieved by taking into account the needs of students from a low socio-economic background. Currently, Malta does not have a national policy covering mobility with a focus on students from disadvantaged groups (European Commission/ EACEA/ Eurydice, 2020b and 2022).

Annex I: Key indicators sources

| Indicator | Source |

|---|---|

| Participation in early childhood education | Eurostat (UOE), , educ_uoe_enra21 |

| Low achieving eighth-graders in digital skills | IEA, ICILS |

| Low achieving 15-year-olds in reading, maths and science | OECD (PISA) |

| Early leavers from education and training | Main data: Eurostat (LFS), edat_lfse_14 Data by country of birth: Eurostat (LFS), edat_lfse_02 |

| Exposure of VET graduates to work based learning | Eurostat (LFS), edat_lfs_9919 |

| Tertiary educational attainment | Main data: Eurostat (LFS), edat_lfse_03 Data by country of birth: Eurostat (LFS), edat_lfse_9912 |

| Participation of adults in learning | Data for this EU-level target is not available. Data collection starts in 2022. Source: EU LFS. |

| Equity indicator | European Commission (Joint Research Centre) calculations based on OECD’s PISA 2018 data |

| Upper secondary level attainment | Eurostat (LFS), edat_lfse_03 |

| Public expenditure on education as a percentage of GDP | Eurostat (COFOG), gov_10a_exp |

| Public expenditure on education as a share of the total general government expenditure | Eurostat (COFOG), gov_10a_exp |

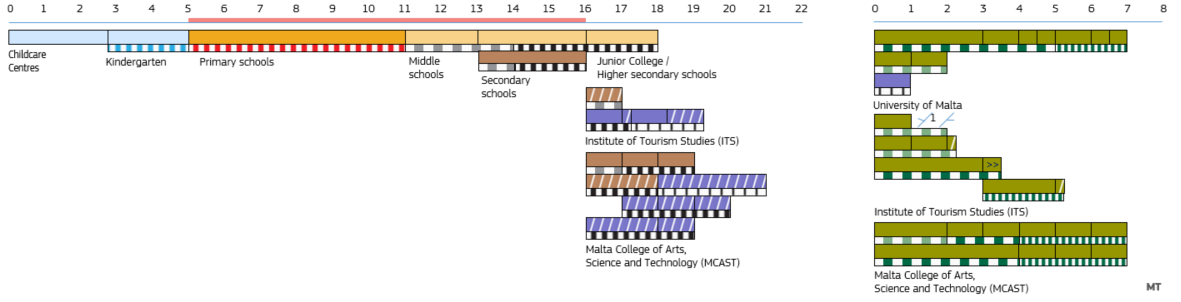

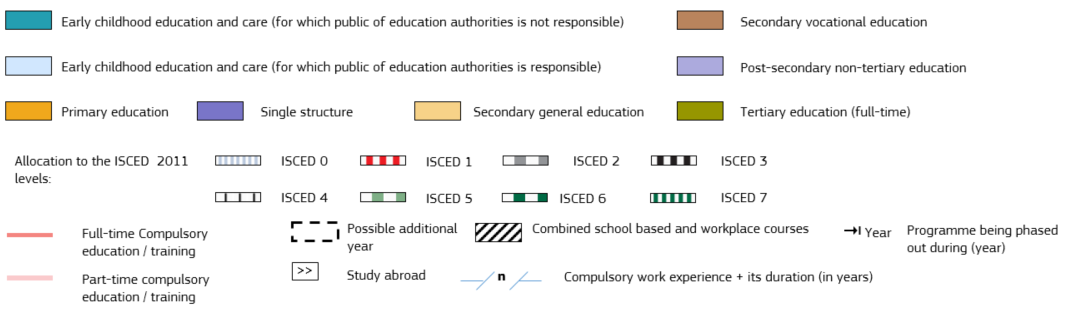

Annex II: Structure of the education system

Please email any comments or questions to:

Publication details

- Catalogue numberNC-AN-22-014-EN-Q

- ISBN978-92-76-55996-2

- ISSN2466-9997

- DOI10.2766/241068